The Impact of Job Characteristics on Social and Human Service Workers

Reva I. Allen/Eric G. Lambert/Sudershan Pasupuleti/Terry Cluse-Tolar/Lois A. Ventura, Department of Social Work, University of Toledo

1

In many career fields, there is a tendency to try to find the right person for the job instead of trying to make the job right for the person. Koeske and Kirk (1995) wrote, “Social work administrators presume that there are certain characteristics of human service workers that predispose some of the workers to thrive in a particular job while workers with other characteristics are more likely to dislike the job or do poorly” (p. 15). Additionally, some administrators of social and human service agencies appear to be more concerned with the impact of workers on their agency than the impact of the organization on workers. “Blaming the employee” focuses the attention away from the real causes (Arches 1991).

It is true that social and human service workers can and do have meaningful effects on their employing organizations. It is, however, naive to assume that employees are not affected by the organization. It is reasonable to assume that many employees who have negative or positive impacts on the employing organization do so because of how they were treated at work. The work environment has real and lasting effects on most employees.

It is generally theorized that the work environment influences employees mainly through their attitudinal states, and these attitudinal states in turn shape staff’s intentions and behaviors. Two of the most important employee factors are job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Job satisfaction is generally viewed as the degree to which a person likes his or her job and is frequently studied across a wide array of disciplines (Spector 1996; Cranny/ Smith/ Stone 1992), including social and human service professions. Organizational commitment is generally defined as having the core elements of loyalty to the organization, identification with the organization (e.g., pride in the organization and internalization of the goals of the organization), and involvement in the organization (e.g., personal effort made for the sake of the organization) (Mowday/Steers/Porter 1979). It is a “bond to the whole organization, and not to the job, work group, or belief in the importance of work itself” (Lambert/Barton/Hogan 1999, 100). High levels of job satisfaction and organizational commitment have been linked to extra work effort, creativeness, innovativeness, productivity and positive employee social responsibility (Clegg/ Dunkerley 1980; Mathieu/Zajac 1990; Witt 1990). Conversely, low levels of job satisfaction and organizational commitment have been associated with reduced performance, psychological withdrawal, burnout, tardiness, absenteeism, and turnover (Barber 1986; Cotten/Tuttle 1986; Farrell Stamm, 1988; Hulin/Roznowski/Hachiya 1985; Mathieu/Zajac 1990; Poulin/Walter 1992; Vinokur-Kaplan/Jayaratne/Chess 1994).

While job satisfaction has received a fair amount of attention in the social work and human services literature, there has been little research on organizational commitment among this important group of workers. Because of a lack of empirical evidence, it is unclear whether the same determinants of job satisfaction also apply to organizational commitment among social and human service staff. In this study, job stress, supervision, job variety, and job autonomy were examined for their effects on the job satisfaction and organizational commitment.

Without dedicated, motivated, committed, satisfied, and skilled staff, a social agency will not succeed in its mission in the long run. Clients, families of clients, fellow staff, the organization as a whole, and even society, all suffer from this failure. Therefore, it is crucial to understand how job characteristics impact the staff of social and human service agencies. Without empirical research, it is possible that changes to the work environment could be made based on rhetoric or intuition rather than on a sound scientific foundation.

2 Literature Review

Work environments are more than just tangible, physical structures. They are also social and psychological structures. While many work environments are complex, they can be divided into two main dimensions, organizational structure and job characteristics. Organizational structure refers to how an organization arranges, manages, guides, and operates itself (Oldham/Hackman 1981), and includes areas such as centralization, formalization, instrumental communication, and legitimacy (Lincoln/Kalleberg 1990). Job characteristics pertain to the attributes associated with a particular job (Hackman/Lawler 1971), and include areas such as job variety, skill variety, job stress, task significance, task identity, and supervision (Hackman/Lawler 1971). The four job characteristics examined in this study were job stress, job autonomy, job variety, and supervision.

Job stress is generally defined in the literature as an employee’s feelings of job-related hardness, tension, anxiety, frustration, worry, emotional exhaustion and distress (Cartwright/Cooper 1997). While there have been several studies that have explored the causes of job stress and its impact (Cushman/Evans/Namerow 1995; Gibson/McGrath/Reid 1989; Himle/Jayaratne/Thyness 1989; Siefert/Jayaratne/Chess 1991), far less research has examined the impact of job stress on job satisfaction of social and human service workers. Gellis (2001) observed that job stress was negatively correlated with job satisfaction among hospital social workers. Conversely, no relationship was found in multi-variate analysis between job stress and job satisfaction among social workers who mainly worked with elderly clients (Poulin1994).

The job characteristics of job autonomy and job variety have been studied to a lesser degree. Job autonomy is generally defined as the degree of freedom that employees have in making job-related decisions (Agho/Mueller/Price 1993). It has also been defined as “independence in thought, goal-setting, and determination of work methods” (Buffum/Ritvo 1984, 39). It is different from input into decision-making, which deals with issues at the organizational or policy level and not everyday job issues. Job variety is the degree of variation in the job (Price/ Mueller 1986). Some research measures its opposite, routinization. Some jobs require role performance that is highly repetitive, while other jobs have significant degree of variety in the required tasks and how they are performed (Mueller/Boyer/ Price/Iverson 1994). According to Ross and Reskin (1992), “job autonomy and nonroutine work signal occupational self-direction,” which is a positive outcome for most employees.

Control over decision-making and job autonomy have both been found to be linked with social work job satisfaction (Arches 1991; Poulin 1994). Barber (1986) reported that challenging duties were related to the job satisfaction of social workers. Similarly, it was observed that skill variety was positively associated with job satisfaction of workers across 22 human service organizations (Glisson/Durick 1988). In a combined measure of both job autonomy and job variety, called job challenge, Vinokur-Kaplan et al. (1994) found it was positively correlated to job satisfaction of social workers.

Finally, another important job characteristic is supervision. Most employees have a direct supervisor, a person who guides and directs them. Supervision can and does drastically vary, not only from organization to organization, but also within an agency. At one end of the continuum are supervisors who provide quality, open, motivating, and supportive supervision. At the other end of the continuum are supervisors who are inconsistent, do not motivate employees to meet high standards, have poor communication styles, and are unfriendly and unfair.

Poor supervision was found to be linked to burnout (Cherniss 1980a; Itzhaky/Aviad-Hiebloom 1998) and job satisfaction (Cherniss/Egnatios 1978) among social and human service workers. Among social workers who mainly worked with elderly clients and Southwestern social workers, supportive supervision was associated with increased job satisfaction (Poulin1994; Rauktis/ Koeske 1994). Supervision was an important predicator of gerontological social worker job satisfaction (Poulin/Walter1992).

The effects these job characteristics have on the organizational commitment of social and human service workers have received little, if any, attention in the empirical literature, and, as such, the impact of these job characteristics are not fully understood, particularly for organizational commitment. Among human service workers, job variety was found to have a small but statistically significant relationship with organizational commitment (Glisson/Durick 1988). Finally, there has been little, if any, empirical research that has examined the impact of job characteristics on both job satisfaction and organizational commitment of social and human service workers at the same time.

Glisson and Durick (1988) argued that “individual studies have tended to investigate either the predictors of satisfaction or those of commitment, making comparisons impossible between the relative effects on satisfaction and commitment of each predictor studied” (p. 61). Thus, there is a need to study the impact of job characteristics on job satisfaction and organizational commitment among social and human service workers simultaneously.

3 Research Questions and Hypotheses

There were two main research questions in this study. First, how do the job characteristics of job stress, job autonomy, job variety, and supervision affect the job satisfaction of social and human service workers. Second, how do these same job characteristics affect the organizational commitment of social and human service employees.

Job stress is hypothesized to have an inverse effect on social and human service staff job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Job stress is a negative condition for most people. As the level of stress from the job increases, the more likely an individual will see the job negatively and blame the organization. Conversely, an employee who experiences little stress from work will probably be more likely to hold favorable views toward his/her job and see the organization in a more favorable light.

Job autonomy is hypothesized to have a positive impact on job satisfaction and organizational commitment of social and human service workers. Most adults like to have a degree of control in what they do and how they accomplish a given task (Bruce/Blackburn 1992). Those persons with little say in how they do their job and related tasks will probably be more frustrated by their jobs, thus leading to a decrease in job satisfaction. Additionally, as Covey (1989) wrote “Without involvement, there is no commitment” (p.143). Therefore, employees should be more willing to identify with and extend effort towards those organizations that give them greater degree of control over their jobs, and as such, become more committed.

Job variety is hypothesized to have a positive effect on both the job satisfaction and organizational commitment among social and human service workers. Most people do not enjoy repetitive jobs. Workers tend to be appreciative of those organizations that provide them with jobs that allow them to experience and learn new things. This, of course, allows the organization to be seen in a more positive light, which translates to higher levels of organizational commitment.

Open, supportive, motivating, and quality supervision is hypothesized to have a positive effect on the job satisfaction and organizational commitment of social and human service staff. Research by Cherniss (1980a, 1980b) illustrated the importance of supervision in the development of positive attitudes among employees. Supervisors are expected to give direction and feedback necessary for employees to complete their tasks within organizational specifications (Bruce/Blackburn 1992;). Workers look to their supervisors to help them cope with the demands of the job (Poulin 1994). For most line staff, supervisors represent the organization. If supervisors are perceived as failing, particularly in terms of support and consideration, employees are less likely to be satisfied with their work and committed to the organization (Babin/Boles 1996; Glisson/Durick1988). On the other hand, employees who perceive supervisors as doing a good job in terms of consideration, support, direction, and guidance, should be more likely to report positive feelings toward their job and the organization.

4 Methods

In the fall of 2002, a single mailing of a survey was sent to social work and human service workers at a wide array agencies in the Northwest Ohio area. Due to sick leave, temporary reassignment, annual vacation leave, turnover, training, etc., it was estimated that approximately 500 employees were available at the time of the survey. To improve the response rate, a raffle of cash prizes ranging from $25 to $100 was done. A total of $325 was given away. Respondents were informed that by returning a survey, whether completed or not, they were eligible to be included in the raffle drawing. In order to be part of the raffle, respondents needed to place their name and phone number on the back of the return self-addressed stamped business envelope. To ensure the anonymity of the respondents, the opened return envelopes were placed in a separate pile from the returned survey, with no identifying marks placed on the surveys. A total of 255 usable surveys were returned. Respondents represented various administrative levels from a wide array of social and human service workers.

5 Measures

The two dependent variables in this study were job satisfaction and organizational commitment. The two major methods of measuring job satisfaction are facet/dimensional measures and global measures (Cranny et al. 1992). Faceted measures of job satisfaction focus on narrow areas of job tasks, such as satisfaction with pay, satisfaction with supervision, and satisfaction with co-workers (Smith/Kendall/Hulin 1969), and these sub-dimensional measures are summed together to form an overall job satisfaction measure. Global measures of job satisfaction are concerned with the broader domain of an individual’s satisfaction with his or her overall job, rather than with specific facets, and the person is asked his or her overall satisfaction with his or her job (Brayfield/Rothe 1951). It is argued that global measures are more appropriate for measuring overall job satisfaction and have fewer methodological concerns than measures which sum the facets (Ironson/Smith/Brannick/Gibson/Paul 1989). Therefore, a global index measure of job satisfaction, consisting of five items adapted from Brayfield and Rothe (1951), was used (Cronbach’s alpha = .82). All measures used to form the indices in this study are presented in the appendix.

The two major methods of measuring organizational commitment are behavioral and attitudinal. Behavioral measures are often referred to as calculative commitment because an employee “calculates” in some manner the costs and benefits of working for a given organization (e.g., monetary, social, physical, psychological, lost opportunities, etc.). These calculations determine the level of commitment to the organization. Attitudinal commitment measures are primarily concerned with emotional, mental, or cognitive bonds to an organization, such as loyalty, wanting to belong, attachment, belief in the value system and goals of the organization, (Mowday et al. 1979). These attitudinal and affective factors determine the level of commitment towards the employing organization. An attitudinal measure was employed in this study, and this type of measure is consistent with the definition of organizational commitment provided earlier. Specifically, organizational commitment was measured by six items adopted from the Organizational Commitment Questionnaire (Mowday/Porter/Steers 1982). The Organizational Commitment Questionnaire is generally viewed as a reliable and valid measure (Mathieu/Zajac 1990). The six items were summed together to form an index of organizational commitment (Cronbach’s alpha = .88).

The four major independent variables in this study were job stress, job autonomy, job variety, and supervision. Job stress was measured using four items derived from Crank, Regoli, Hewitt, and Culbertson (1995). The four items were summed to together to form a job stress index (Cronbach’s alpha = .80). Job autonomy was measured using two items from Curry, Wakefield, Price, and Mueller (1986). The two items were summed together to form an index (Cronbach’s alpha = .73). Job variety was measured using five items adapted from other studies that measured job variety/routinization (Curry et al. 1986; Finlay/Martin/Roman/Blum 1995; Mueller et al. 1994). The five items were summed together to form a job variety index (Cronbach’s alpha = .73). Finally, supervision was measured using ten items from a variety of sources. The ten items were summed together to form an index of supervision (Cronbach’s alpha = .80).

A total of seven personal and work related characteristics were selected as control variables. Specifically, gender, age, tenure, race, marital status, education, and supervisory status were included as control variables. Gender was measured as dichotomous variable representing whether the respondent was female (0) and male (1). Age was measured in continuous years. Tenure at the current employer was also measured in continuous years. In terms of race, 84% of the respondents were white, 12% were black, 3% were Hispanic, 0.4% were Asian American, none were Native American, and 1% were other. The measure of race was collapsed into a dichotomous variable representing whether the respondent was white (1) or non-white (0). Eighty-four percent of the respondents were white and 16% were non-white. In terms of martial status, 61% of the respondents were married, 13% were divorced, 1% were widowed, 12% were single with a partner, and 12% were single with no partner. Martial status was collapsed into a dichotomous variable representing in a person was married (1) or not (0). In terms of the highest educational level reported, 4% of the respondents had a high school diploma or GED, 7% had some college but no degree, 12% had an associates degree, 51% had a bachelors degree, 27% had a masters degree or higher. Education was left as an ordinal level measure, ranging from 1 = high school to 5 = masters or higher. Finally, a dichotomous variable measuring whether the respondent was a supervisor of other staff or not was created. About 40% of those surveyed indicated that they supervised others at work.

6 Results

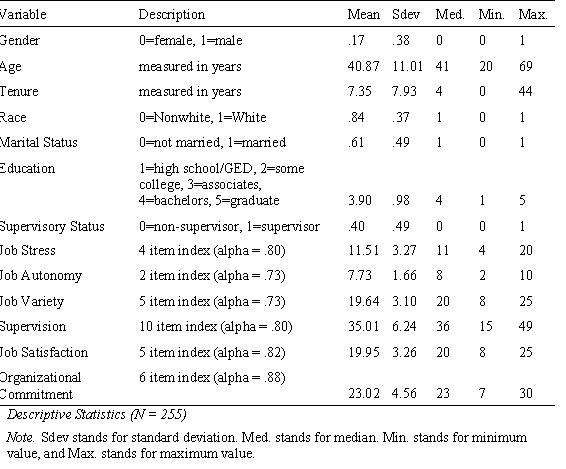

Descriptive statistics for the measures used in this study are presented in Table 1. There appeared to be significant variation in both the dependent and independent variables. Most respondents were female, and the average age of the respondents was early to middle forties. Most had worked slightly over seven years at their current employer and had a bachelors degree. The vast majority were White, married, and were not supervisors of other employees.

Table 1

Figure 1: Descriptive Statistics

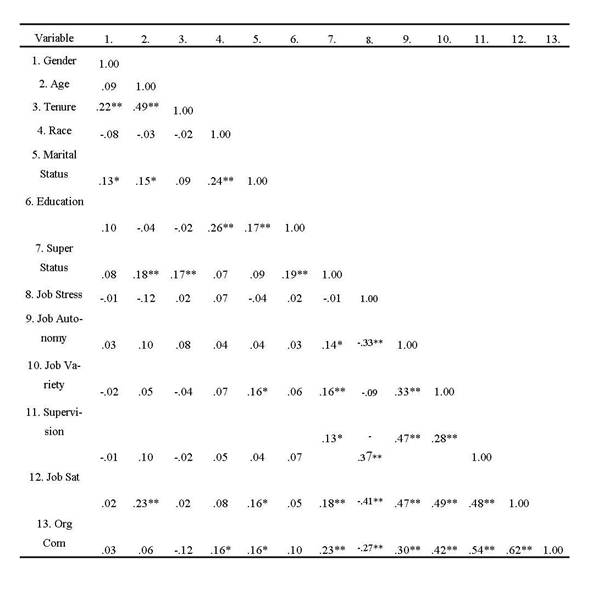

The correlations among the variables in the study are presented in Table 2. As hypothesized, all the job characteristic variables had statistically significant correlations with both job satisfaction and organizational commitment. All the job characteristic variables had a positive correlation with job satisfaction and organizational commitment except job stress which had a negative correlation with both. Each of the four job characteristics had similarly sized correlations with job satisfaction. For organizational commitment, supervision had the largest size correlation, followed by job variety. Job autonomy and job stress had similarly sized correlations.

Among the control variables, age, marital status, and supervisory status all had statistically significant correlations with job satisfaction. As age increased, so to did job satisfaction. Those who were married and those who were supervisors generally reported higher levels of job satisfaction. Race, marital status, and supervisory status all had statistically significant correlations with organizational commitment. White respondents generally reported higher levels of commitment than did Nonwhite respondents. Married persons and supervisors generally had higher levels of organizational commitment as compared to non-married and non-supervisory employees. Finally, while not the focus of this study, it was interesting to observe that job satisfaction had a large, significant correlation with organizational commitment.

Table 2

Zero Order Pearson’s r Correlations (N = 255)

Zero Order Pearson’s r Correlations (N = 255)

Figure 2: Correlations

Note. See Table 1 for how variables were coded. Super Status stands for supervisory status. Job Sat stands for job satisfaction, and Org Com stands for organizational commitment.

* p 0.05. ** p 0.01

An Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression equation was estimated with job satisfaction as the dependent variable and the control variables, job stress, job autonomy, job variety, and supervision as the independent variables. Results are presented in Table 3. Based upon the correlation matrix in Table 2, the Variation Inflation Factor (VIF) statistic, and the tolerance statistic, there appeared to be no issue with collinearity or multicollinearity. As hypothesized, all four job characteristics had a statistically significant impact on job satisfaction. As job stress increased, job satisfaction decreased. As job autonomy and job variety increased, so to did job satisfaction among the social and human service workers. Quality, supportive, and open supervision was associated with more satisfied employees. In terms of the control variables, only age had a significant relationship. As age increased, job satisfaction also rose. Based upon the standardized regression coefficient, job variety had the greatest magnitude of impact on job satisfaction, followed by job stress and supervision which had similar sized effects. Job autonomy and age had similarly sized effects, but were almost half the size of the effect of job variety. Finally, about 48% of the variance of job satisfaction in this study was accounted for by the four job characteristics and the seven control variables.

Table 3: OLS Regression Results for the Impact of Job Characteristics on the Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment Of Social And Human Service Workers

FigureF

Figure 3: OLS Regression Results

Note. b represents the unstandardized OLS regression coefficient. SE (b) represents the estimated standard error of the slope, and B represents the standardized OLS regression coefficient. See Table 1 legend for how variables were coded. (N = 255)

* p 0.05. ** p 0.01

Another OLS regression equation was computed with organizational commitment as the dependent variable. The results are reported in Table 3. Based upon the correlation matrix in Table 2, the Variation Inflation Factor (VIF) statistic, and the tolerance statistic, there appeared to be no issue with collinearity or multicollinearity. As hypothesized, job variety and supervision had significant impacts on organizational commitment of social and human service employees. Job autonomy and job stress, however, did not have significant effects. Among the control variables, tenure, race, and supervisory status all had significant effects. As tenure increased, organizational commitment dropped. On average, White respondents reported higher levels of organizational commitment that did Nonwhite respondents. Supervisors in general had higher levels of commitment than non-supervisors.

In looking at the size of effects (i.e., B in Table 3), supervision by far had the greatest magnitude of effect, more than twice that of job variety which had the second largest impact. The third and fourth largest effects were by tenure and supervisory status, which had similarly sized effects. Race had the smallest effect, one-fourth that of supervision. Finally, the four job characteristic indexes and the seven control measures explained about 43% of the variance of the organizational commitment measure.

7 Discussion and Conclusion

It appears that all four job characteristics are important determinants of job satisfaction of social and human service workers. Because they deal with the job, it was expected that they would help shape job satisfaction. Thus, areas that need to be addressed to improve the job satisfaction of social and health workers are job stress, better supervision, and increases in job autonomy and job variety.

It is unclear why age was significantly related to job satisfaction. It could be the results of aging, cohort socialization, or life/work cycle (Armentor / Forsyth, 1995). According to the aging explanation, as people grow older they become more satisfied with things than they were when they were younger, including their jobs (Kalleberg / Loscocco, 1983). The cohort explanation is that each cohort has different views of what they expect from their jobs, and these different values and expectations can lead to more or less job satisfaction (Armentor / Forsyth, 1995; Kalleberg / Loscocco, 1983). The life/work cycle explanation holds that older workers tend to be in better jobs in terms of the work being done, pay, and security than younger employees, and this leads to increased job satisfaction (Armentor / Forsyth, 1995). The data in this study cannot determine which explanation best explains the observed positive relationship between age and job satisfaction. It is clear that the positive relationship for age among the social and human service employees in this study is consistent with that observed with workers in other fields (Dantzker, 1994; Kalleberg / Loscocco, 1983; Lincoln / Kalleberg, 1990). Moreover, several other studies have found age to be related to job satisfaction, with older social and human service workers more satisfied (Jayaratne, Tripodi, / Chess, 1983; McNeely, 1992)

While age had a significant impact on job satisfaction, it is more important to note that the other six job characteristics had insignificant effects in the regression model. In the literature, there are two general viewpoints on the factors that influence workers’ attitudes and behaviors (Van Voorhis, Cullen, Link, / Wolfe, 1991). The first is referred to as the Individual Importation Model. This approach sees workers’ reactions mainly as the result of personal characteristics, such as age, tenure, race, gender, position, personality, etc, which they bring with them into the organization. The second approach is the Work Environment Model, which views employees’ attitudes and behaviors as predominately shaped by the work environment. The results of this study tend to support the viewpoint that the work environment is more important in influencing the job satisfaction of workers than are personal characteristics, at least for social and human service workers. In fact, the amount of job satisfaction variance explained by the four job characteristics was far greater than that explained by all seven personal characteristics variables (i.e., R2 = .42 versus .10).

While the four job characteristics are salient determinants for job satisfaction, the same cannot be said for organizational commitment. Only two of the four, supervision and job variety, had significant effects. Supervisors are usually seen as part of the management, and to many employees, management represents the structure of the employing organization. Eisenberger, Fasolo, and Davis-Lamastro (1990) contend that commitment increases through noticing and rewarding individual efforts. This is probably one of the reasons why supervision was linked to organizational commitment in this study. Supervision, while a job characteristic, is also an authority figure in the organization (Glisson / Durick, 1988). Thus, not only does supervision directly affect workers and how they do their jobs, but it also represents the organization.

Job variety had a significant impact on social and human service staff organizational commitment as well. It appears that social and human social workers want jobs that have variety and allow them to learn new things. In addition, supervisory status, race, and tenure had significant relationships with organizational commitment. It makes intuitive sense that supervisors would be more committed than non-supervisory staff. They are part of management, and that typically means that they have greater input into the administration of the organization, greater job autonomy, and more job variety than do line staff. As such, they are probably more committed to the organization. In this study, White respondents generally reported higher levels of organizational commitment as compared to Nonwhite respondents. It could be that Nonwhite respondents may have had lower organizational commitment than White respondents because of a perception of discrimination in the workplace or it could have been a chance finding. This is an interesting finding that needs further study.

It was very surprising to observe that tenure was inversely related to organizational commitment among the social and human service workers in this study. Among workers in other fields, if there is a relationship observed between tenure and organizational commitment, it is generally a positive one (Mathieu / Zajac, 1990). According to research in other areas, tenure is generally linked to increased organizational support and benefits (Osipow, Doty, / Spokane, 1985), which should lead to increased commitment. This was not observed here. It could be that the inverse relationship may due to burnout. However, in this study, there is no support for this explanation. There was no significant correlation between tenure and job stress. It could be that those with more tenure have become disillusioned with their promotional organizations and the organization overall. It is also possible that the relationship was due to random chance. Clearly, more research is needed to establish whether tenure is negatively associated with organizational commitment among social and human service workers, and, if so, why.

As with job satisfaction, the results appear to support the viewpoint that the work environment is very important in shaping the organizational commitment, even more so than personal characteristics. The amount of organizational commitment variance explained by the four job characteristics was far greater than that explained by the seven personal characteristics variables (i.e., R2 = .38 versus .08).

Additional research on the subject is needed. This was only a single study of social and human service staff across Northwestern Ohio. Future research should work to replicate the findings reported here on other social work and human service settings across different locales. In addition, the impact of other work environment areas needs to be studied on both job satisfaction and organizational commitment, an area largely ignored in the social work staff literature.

There are administrative implications. The results suggest that in order to improve social and human service staff job satisfaction and organizational commitment, administrators need to concentrate on job characteristics. This should not only increase the job satisfaction and organizational commitment of workers, but ultimately reduce burnout, absenteeism, turnover, and, at the same time, increase morale, performance, and the quality of service provided to clients. The job characteristics studied can be changed by administrators by job redesign, job rotation, stress management training, training for supervisors, and allowing workers greater input into their jobs. It is important to note that organizations cannot only positively impact their employees but they can negatively impact them as well. Administrators must be willing to make the changes necessary to enhance the job satisfaction and organizational commitment of their employees. For social organizations with dissatisfied and uncommitted workers, doing nothing fails to correct the problem and probably makes it worse.

If administrators are forced to concentrate their efforts and resources towards a more focused goal than all four job characteristics, it is recommended that they concentrate on job variety and supervision in the short run, since both strongly affect both job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Job autonomy and job stress only impact job satisfaction. It is important to remember that the results indicate that in the long run, administrators of social and human service agencies should focus on all four job characteristics.

In closing, Poulin (1994) argued that “increasing the job satisfaction of social workers is a critical issue facing the profession” (p. 21). We not only agree with this statement, but contend that increasing the organizational commitment of social and human service workers is paramount as well. Social organizations are client-centered. Their primary purpose is to help others. Therefore, social organizations need to be aware of the impact of the work environment on employees. The knowledge of and the ability to understand the determinants of social and human service employee affective states, attitudes, and behaviors is critical for all parties involved, including administrators, employees, clients, academicians, and society in general. In order to improve the job satisfaction and organizational commitment of workers, administrators of social agencies need a commitment to create a supportive work environment. One way of doing this is concentrating on the job characteristics of supervision, job variety, job stress, and job autonomy. Because of the critical role they place in society and the number of people with whom they interact, we encourage researchers and administrators to continue the focus on the impact of the work environment on social and human service workers.

References

Agho, A., and Mueller, C., and Price, J. 1993: Determinants of employee job satisfaction: An empirical test of a causal model., in: Human Relations, 46, pp. 1007-1027.

Arches, J. 1991: Social structure, burnout, and job satisfaction, in: Social Work, 36, pp. 202-206.

Armentor, J., and Forsyth, C. 1995: Determinants of job satisfaction among social workers, in: International Review of Modern Sociology, 25(2), pp. 51-63.

Babin, B., and Boles, J. 1996: The effect of perceived co-worker involvement and supervisor support on service provider role stress, performance, and job satisfaction, in: Journal of Retailing, 72, pp. 57-75.

Barber, G. 1986: Correlates of job satisfaction among human service workers, in: Administration in Social Work, 10 (1), pp. 25-39.

Brayfield, A., and Rothe, H. 1951: An index of job satisfaction, in: Journal of Applied Psychology, 35, pp. 307-311.

Bruce, W., and Blackburn, J. 1992: Balancing job satisfaction and performance: A guide for the human resource professional. Westport, CT: Quorum Books.

Buffum, W., and Ritvo, R. 1984: Work autonomy and the community mental health professional: Guidelines for managemen, in: Administration in Social Work, 8 (4), pp. 39-54.

Cartwright, S., and Cooper, C. 1997: Managing workplace stress. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Cherniss, C. 1980a: Staff burnout: Job stress in the human services. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Cherniss, C. 1980b: Professional burnout in human service organizations. New York: Praeger.

Cherniss, C., and Egnatios, E. 1978: Is there job satisfaction in community mental health?, in: Community Mental Health Journal, 14, 309-318.

Clegg, S., and Dunkerley, D. 1980: Organization, class, and control. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Cotten, T., and Tuttle, J. 1986: Employee turnover: A meta-analysis and review with implications for research, in: Academy of Management Review, 11, pp. 55-70.

Covey, S. 1989: The 7 habits of highly effective people: Powerful lessons in personal change. New York: Simon and Shuster.

Crank, J., and Regoli, R., and Hewitt, J., and Culbertson, R. 1995: Institutional and organizational antecedents of role stress, work alienation, and anomie among police executives, in: Criminal Justice and Behavior, 22, pp. 152-171.

Cranny, C., and Smith, P., and Stone, E. (eds.) 1992: Job satisfaction: How people feel about their jobs and how it affects their performance. New York: Lexington Books.

Curry, J., and Wakefield, D., and Price, J., and Mueller, C. 1986: On the causal ordering of job satisfaction and organizational commitment, in: Academy of Management Journal, 29, pp. 847-858.

Cushman, L., and Evans, P., and Namerow, P. 1995: Occupational stress among AIDS social service providers,m in: Social Work in Health Care, 21(3), pp. 115-131.

Dantzker, M. 1994: Measuring job satisfaction in police departments and policy implications: An examination of a mid-size, southern police department, in: American Journal of Police, 13, pp. 77-101.

Eisenberger, R., and Fasolo, P., and Davis-Lamastro, V. 1990: Perceived organizational support and employee diligence, commitment, and innovation, in: Journal of Applied Psychology, 75, pp. 51-59.

Farrell, D., and Stamm, C. 1988: Meta-analysis of the correlates of employee absence. Human Relations, 14, pp. 211-227.

Finlay, W., and Martin, J., and Roman, P., and Blum, T. 1995: Organizational structure and job satisfaction: Do bureaucratic organizations produce more satisfied employees?, in: Administration and Society, 27, pp. 427-450.

Gellis, Z. D. 2001: Job stress among academic health center and community hospital social workers, in: Administration in Social Work, 25(3), pp. 17-33.

Gibson, F., and McGrath, A., and Reid, N. (1989). Occupational stress in social work. British Journal of Social Work, 19, pp. 1-18.

Glisson, C., and Durick, M. 1988: Predictors of job satisfaction and organizational commitment in human service organizations, in: Administrative Quarterly, 33, pp. 61-91.

Hackman, J., and Lawler, E. 1971:. Employee reactions to job characteristics, in: Journal of Applied Psychology, 55, pp. 259-286.

Himle, D., and Jayaratne, S., and Thyness, P. 1989: The buffering effects of four types of supervisory support on work stress., in: Administration in Social Work, 13(1), pp. 19-34.

Hulin, C., and Roznowski, M., and Hachiya, D. 1985: Alternative opportunities and withdrawal decisions: Empirical and theoretical discrepancies and an integration, in: Psychological Bulletin, 97, pp. 233-250.

Ironson, G., and Smith, P., and Brannick, M., and Gibson, W., and Paul, K. 1989: Construction of a job in general scale: A comparison of global composite and specific measures, in: Journal of Applied Psychology, 74, pp. 193-200.

Itzhaky, H., and Aviad-Hiebloom, A. 1998: How supervision and role stress in social work affect burnout, in: Arete, 22(2), pp. 29-43.

Jayaratne, S., and Tripodi, T., and Chess, W. 1983: Perceptions of emotional support, stress, and strain by male and female social workers, in: Social Work Research / Abstracts, 19, pp. 19-27.

Kalleberg, A., and Loscocco, K. 1983: Aging, values, and rewards: Explaining age differences in job satisfaction, in: American Sociological Review, 48, pp. 78-90.

Koeske, G., and Kirk, S. 1995: The effect of characteristics of human service workers on subsequent morale and turnover, in: Administration in Social Work, 19(1), pp. 15-31.

Lambert, E., and Barton, S., and Hogan, N. 1999: The missing link between job satisfaction and correctional staff behavior: The issue of organizational commitment, in: American Journal of Criminal Justice, 24, pp. 95-116.

Lincoln, J., and Kalleberg, A. 1990: Culture, control and commitment: A study of work organization and work attitudes in the United States and Japan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mathieu, J., and Zajac, D. 1990: A review and meta-analysis of the antecedents, correlates, and consequences of organizational commitment, in: Psychological Bulletin, 108, pp. 171-194.

McNeely, R. L. 1992: Job satisfaction in the public social services: Perspectives on structural, situational factors, gender, and ethnicity, in: Hasenfeld, Y. (ed.): Human services as complex organizations (pp. 224-255). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Mowday, R., and Porter, L., and Steers, R. 1982: Employee-organization linkages: The psychology of commitment, absenteeism and turnover. New York: Academic Press.

Mowday, R., and Steers, R., and Porter, L. 1979 The measurement of organizational commitment, in: Journal of Vocational Behavior, 14, pp. 224-247.

Mueller, C., and Boyer, E., and Price, J., and Iverson, R. 1994:. Employee attachment and noncoercive conditions of work, in: Work and Occupations, 21, pp. 179-212.

Oldham, G., and Hackman, J. 1981: Relationships between organizational structure and employee reactions: Comparing alternative frameworks, in: Administrative Science Quarterly, 26, pp. 66-83.

Osipow, S., and Doty, R., and Spokane, A. 1985:. Occupational stress, strain, and coping across the life span, in: Journal of Vocational Behavior, 27, pp. 98-108.

Poulin, J. (1994): Job task and organizational predictors of social worker job satisfaction change: A panel study, in: Administration in Social Work, 18(1), pp. 21-38.

Poulin, J., and Walter, C. 1992: Retention plans and job satisfaction of gerontological social workers, in: Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 19, pp. 99-114.

Price, J., and Mueller, C. 1986:Absenteeism and turnover among hospital employees. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Rauktis, M., and Koeske, G. 1994: Maintaining social work morale: When supportive supervision is not enough, in: Administration in Social Work, 18(1), pp. 39-60.

Ross, C., and Reskin, B. 1992: Education, control at work, and job satisfaction, in: Social Science Research, 21, pp. 134-148.

Siefert, K., and Jayaratne, S., and Chess, W. 1991: Job satisfaction, burnout, and turnover in health care social workers, in: Health and Social Work, 16, pp. 193-202.

Smith, P., and Kendall, L., and Hulin, C. 1969: The measurement of satisfaction in work and retirement. Chicago: Rand-McNally.

Spector, P. 1996: Industrial and organizational psychology: Research and practice. New York: John Wiley.

Van Voorhis P., and Cullen, F., and Link, B., and Wolfe, N. 1991: The impact of race and gender on correctional officers’ orientation to the integrated environment, in: Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 28, pp. 472-500.

Vinokur-Kaplan, D., and Jayaratne, S., and Chess, W. 1994: Job satisfaction and retention of social workers in public agencies, non-profit agencies, and private practice: The impact of workplace conditions and motivators., in: Administration in Social Work, 18(3), pp. 93-121.

Witt, L. 1990: Person-situation effects and sex differences in the prediction of social Responsibility, in: Journal of Social Psychology, 130, pp. 543-553.

8 Appendix

The below items were answered by a 5-point Likert-type of response scale, ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5).

Job Satisfaction

1. I definitely dislike my job (reverse coded).

2. I like my job better than the average worker does.

3. Most days I am enthusiastic about my job.

4. I find real enjoyment in my job.

5. I am very satisfied with my job.

Organizational Commitment

1. I tell my friends that this is a great organization to work for.

2. I feel little loyalty to my employer (reverse coded).

3. I find that my values and the employing organization’s values are very similar.

4. I am proud to tell people that I work here.

5. This place really inspires the best in me in the way of job performance.

6. I really care about the fate of this place.

Job Stress

1. I am usually under a lot of pressure when I am at work.

2. When I’m at work I often feel tense or uptight.

3. I am usually calm and at ease when I’m working (reverse coded).

4. I don’t consider this a very stressful job (reverse coded).

Job Autonomy

1. I have a great deal of freedom as to how I do my job.

2. My job does not allow me much opportunity to make my own decisions (reverse coded).

Job Variety

1. My job has a lot of variety in it.

2. My job requires that I be very creative.

3. I rarely get to do different things on my job (reverse coded).

4. My job requires that I constantly must learn new things.

5. My job is mainly concerned with routine matters (reverse coded).

Supervision

1. My supervisor does little to make it pleasant to work here (reverse coded).

2. My supervisor maintains a definite standard of performance for all employees under his/her command.

3. My supervisor looks out for the personal welfare of employees.

4. My supervisor gives me advance notice of changes.

5. My supervisor encourages me to do my best.

6. My supervisor is friendly and approachable.

7. My supervisor is familiar enough with my job to evaluate me fairly.

8. Supervisors at this place give full credit to ideas contributed by employees.

9. Supervisors often talk down to workers (reverse coded).

10. I have little trust in my supervisor’s evaluation of my work performance (reverse coded).

Author’s

adresses:

Associate Prof Reva I. Allen/Associate Prof Eric

G. Lambert/Assistant Prof Sudershan Pasupuleti/Associate Prof Terry

Cluse-Tolar/Assistant Prof Lois A. Ventura

Department of Social Work

College of Health and Human Services

University of Toledo

HHS 3201, Mailstop 119

Toledo, Ohio 43606

Tel.: 419 530 4397

Fax: 419 5304141

E-mail: Tcluset@UTNet.UToledo.Edu