Different Levels of Policy Change: A Comparison Between the Public Discussion on Social Security in Sweden and in Finland

Christian Kroll / Helena Blomberg, University of Helsinki, Swedish School of Social Science

1 Introduction

The deep economic recession hit Sweden and Finland at the beginning of the 90s, and the fall in public revenues and rapidly growing public debts that followed on it, probably posed a challenge, more severe than ever before experienced, to the extensive Nordic welfare state-type systems of social security in these countries. What remains an issue of debate today is exactly what the cutbacks and restructuring measures taken during (and after) the recession have meant for these countries' welfare systems’ and, even, to what extent any changes made may be ascribed mainly to the economic constraints posed by the recession at all, or rather, to other more long-term societal trends or phenomena. These include globalisation, European integration and/or ideational or ideological shifts among elite groups, mainly in the direction of neo-liberal ideals (cf. Nordlund 2000; Kautto et.al. 1999; Esping-Andersen 2002; Jaeger/Kvist 2003 for reviews of these changes in preconditions).

The answer to the question of the reasons for and effects of cutback measures seems to be at least partly dependent on what indicators are used to assess the development and whether individual programmes or the ideals of the “Nordic welfare state model” are in focus. However, a generalisation of the main results of different studies, concerning the development both in Sweden and Finland, could perhaps allow for a division of studies into two broad “camps”.

Thus, for instance, Nordlund (2000,41) concludes, based on the results of a comparative study on changes made in the main social security programmes in four Nordic countries during the 80s and 90s, that, taking into consideration the proportionality between challenges and changes made, the Nordic welfare states ”have shown themselves very durable indeed” (for similar views, see also Lindbom 2001; Huber/Stephens 2002). And where changes have taken place, powerful political sources seem to have counteracted challenges towards the welfare state and ”channelled change in the direction of relatively small modifications of existing programmes”. From his comparative study, Kvist (2000) concluded that none of the Nordic countries left the club of countries belonging to the Nordic welfare state model, although both Sweden´s and Finland´s conformity with the model had weakened during the 90s, and Finland was now regarded as only “more or less in the model”, according to the indicators used. However, Kvist (ibid., 251) assumed at the same time that, as there were limits to expansion, there were also limits to cutbacks “beyond [which] politicians and populations are unwilling to go”. Yet another inter-Nordic comparison, extending up until the mid 90s (Heikkilä et. al. 1999, 267), also concluded that “the obvious potential for restructuring coming from macro-economic, demographic and political pressures had not been manifested in the form of fundamental changes in [..] benefit provision”. However, in this study, the structural and political conditions that had fuelled the changes made so far were believed to have created a still existing potential for welfare reform. Other researchers (e.g. Bergmark et al. 2000) have been of the opinion that it is too soon to say whether the restructurings are merely a temporary decline or a more permanent change of course.

Those who are even less convinced about the survival of the Nordic welfare state model in Sweden and Finland, usually do not challenge the findings on what restructuring measures have been taken, but, rather, how they should be interpreted. The argument for the view that the “Nordic model” has been weakened in significant respects is that the effects of the changes made have to be viewed in sum, and that these, taken together, have had deep-cutting results (Clayton/Pontussen 1998; Anttonen /Sipilä 2000; Lehtonen 2000; Lehtonen /Aho 2000; Sunesson et al. 1998; Hinrichs /Kangas 2003; Blomqvist 2004).

Although factual changes in the welfare system of a country naturally reveals something concerning the intentions behind the policies conducted, because of the multitude of thinkable explanations, they cannot necessarily be interpreted as exhaustive indicators of (possible changes in) the dominating way(s) of thinking on welfare policy issues. This refers to the dominating ideas concerning welfare policy and its aims that prevail among influential elite groups in society at a given point in time.

While those who have found little evidence of a more profound change in the welfare system itself often seem to conclude that there is no evidence of a declining commitment to the principles behind the system, but that changes made should mainly be seen as a response to acute economic hardships during the first half of the 90s (cf. above), others have been more sceptical. For instance Julkunen (2000; 2001) has claimed that the consensus among elite groups concerning the idea and goals of the welfare state, which had existed during many decades, now seems at least to have been weakened. For results that may be seen as pointing in this direction, see e.g. Boréus (1994), Hugemark (1994), Svallfors (1995;1996) for Sweden, Forma (1999), Blomberg and Kroll (1999) for Finland. However, the knowledge about how and how much the way of reasoning among elite groups did change during the 90s, referring to issues of welfare policy is limited so far. It is also unclear as to what extent possible changes seem to have been similar in these two Nordic countries, or whether differences in national-specific conditions seem to have a crucial effect on these issues.

This article attempts to contribute to the knowledge on the questions touched upon above by trying to get a grasp of the dominating ”rationale” behind the reasoning among elite groups in Sweden and Finland before, during and after the 90’s recession, concerning the main social insurance programmes. It is interesting to compare the two countries selected since, in addition to having among the most similar welfare systems in the world, and both being hit by a recession in the 90s, they also are different enough to offer some interesting contrasts, e.g. politically.

We will try to address these questions by analysing statements made by different actors in a selection of Swedish and Finnish newspapers. By focusing on the contents of the press, which is dominated by statements made by various elite groups, the aim is to get as comprehensive a picture as possible of the public discussion on the issue.

Thus, our research questions are the following:

· On a rhetorical level, how questioned has the system of social insurance been in the respective country during the last decades, and how has this materialised? Has it been mainly as suggestions for small downward adjustments or rather as suggestions for fundamental changes in the system?

· How were these suggestions motivated, more often by referring to ideological considerations, mirroring differences in basic policy goals or, rather, mainly referring to structural conditions, such as economic constraints?

· Which actors made these kinds of suggestions/demands?

· How did the rhetoric change on the above dimensions, over the time-span examined and

· What differences were there in these respects between Sweden and Finland?

The next sections will first address the question of how to systematically differentiate between different types of (suggested) changes in the welfare system and its principles. Then, the data used in the analysis and the operationalisation of the individual variables will be presented. The article ends with a presentation and discussion of the main results and their possible implications.

2 Different levels of policy-making and their implications

To identify trends and cross-national variations in the discussion of social security in the public arena, a distinction between three different levels of policy change, according to the magnitude of changes as suggested by Hall (1993), presents a useful starting-point, in the light of the above discussion. Hall distinguishes between the level of overarching policy goals that guide the policy in a certain field (a “policy paradigm”), the level of techniques or policy instruments to attain these goals, and the level of adjustments or precise setting of the instruments, thus allowing for an identification of different levels or orders of policy change.

Policy changes that are limited to adjustments in existing policy instruments (e.g. changing levels of benefits within a social insurance programme), called first order changes, or changes which concern the kind of policy instruments to be used to achieve certain goals (second order changes, e.g. the abolition of an old and introduction of a new pension scheme), are characterised as cases of “normal policy-making”, a process to adjust policy, without challenging the overarching policy goals (ibid., 278-9). Further, changes on these levels are assumed to be mainly expressions of processes of social learning within the State, and experts in the public employ are said to play a primary role in policy innovation (ibid., 288).

In contrast, third order changes imply an overall change in a given policy paradigm, which is defined as "a framework of ideas and standards that specify not only the goals of policy and the instruments that can be used to attain them, but also the very nature of the problems that they are meant to be addressing". Thus, a paradigm shift is marked by "radical changes in the overarching terms of policy discourse" (ibid., 279).[1] In contrast to changes of the first and second order, shifts in the dominant paradigm are thought to come about in response to a broad societal debate, in which various political actors (e.g. political parties and their representatives) play an important role, but in which significant pressure is also placed on the government from the media, as well as from (other) outside interests (ibid., 288). Paradigm shifts are further thought to be most likely initiated by/to require structural conditions or events that prove anomalous within the terms of the prevailing paradigm, events which provide failures that discredit the old paradigm and lead to a wide-ranging search for alternatives, and when a sufficiently elaborated alternative paradigm is at hand.

Though offering an interesting way to separate between different magnitudes of policy change, other authors have pointed to aspects which make their views different from Hall’s view, as regards the nature of and relationship between different orders of change. Hall seems to assume that a change on a higher level will affect lower levels as well, though a possible change “the other way around” is not considered. For instance, Cox (1998), focusing on the relationship between ideas and policies of welfare programme restructuring, argues that every effort to change policy measures within a social policy programme will have an impact on its principles, and to the extent that a change in measures threatens an existing principle, it does so by offering a new one in its place. In an empirical study, Araki (2000) points at how the British Conservatives’ pension policies since WW II have been characterised by a high degree of persistence. This particularly regards the strengthening (and, at the same time, modification) of some core conservative ideological principles guiding pension policy, through the employment of step-wise and increasingly deep-cutting alterations of British pension programmes over time. This “cumulative trend”, it is argued, was mainly assisted by “technical devices”, e.g. setting lower values for state schemes and introducing new policy programmes. In other words, this refers to policy changes that would be characterised as being of the first or second order in Hall’s terms.

Thus, it seems reasonable to expect that small or moderate (suggestions of) adjustments or alterations of social insurance programmes might also challenge, intentionally (or perhaps unintentionally), the principles of the system, thereby negatively affecting the coherence between a programme and the policy paradigm on which the programme in question was originally based. Further, these perspectives also raise questions as to whether policy changes of the first and second order (at least in issues of social policy) can be ascribed mainly to effects of “social learning by experts in the public employ”, or whether actors with mainly politically-motivated ambitions might not also, to a considerable degree engage themselves in changes at the “lower” levels.

On the other hand, any explanation that stresses the importance of political/ideological factors behind changes in the welfare system might tend to take on a “voluntaristic bias”, if it does not give enough credit to economic and other structural factors that, on the one hand, make policies possible, and, on the other, put constraints on them. (Uusitalo 1984; Gough 1979). Therefore, one could also assume that suggestions for small adjustments, or even profound system changes, could be made first and foremost in response to (perceived) changes in the societal environment at large, such as increased/new economic constraints, rather than in response to a wish to change the prevailing policy paradigm because of ideational/ideological considerations. (This, however, does not mean that the type of suggested measures might not still vary according to ideological persuasions.)

To sum up, an analysis of possible changes in the thinking on social security could benefit from making a division between the type of justification presented for the policy measure advocated, on the one hand, and, on the other hand, the type and magnitude of the suggested change in the existing system[2], since there may not necessarily be any given relationship between these factors. Thus, according to this view, a justification presented becomes an independent variable in relation to a suggested change (regardless of its magnitude) of/in the existing system at a given point in time.

According to this approach, a paradigm shift could thus, on the one hand, be marked by a rise in the amount of justifications for policy changes that are not in compliance with the normative basis of the present system, regardless of the magnitude of the policy change itself. But on the other hand, also proposals of (at least fundamental) changes in the system itself, even though not explicitly justified by views conflicting with the present policy paradigm, could be seen as an indication of the present paradigm being challenged.

In the following sections we will turn to the question of the nature of these different variables.

3 Justifications for changes in welfare policy

In this study, justifications for a policy change are taken to mean the basic norms and goals used to legitimise the welfare policy measures advocated. With regard to the situation in the two countries of interest, at the beginning of the period investigated (the late 1980s), the question becomes whether a justification is concordant with the values and norms on which the traditional "Nordic welfare state model" is based, or whether it is based on conflicting normative considerations.

From an ideological perspective, it has been claimed that the Nordic welfare model rests on a “welfare state ideology”. However, this cannot be put on a par with goals of any single political ideology, but corresponds with the traditional aspirations of Social Democrats and social liberals to transfer social tasks from the private and informal sectors to the public sector (Raunio 1995, 208; Boréus 1994; 1997). This “ideology”, however, could also be seen to include other than (at least explicitly) political standpoints, such as the views of different schools of economic thought concerning the desirability of an economic intervention by the public sector through the welfare state. Although not explicitly political in nature, these views have been claimed to strongly correlate with the stands on the political left-right dimension (Pekkarinen 1992, 98; Boréus 1997, 259).

This last aspect is of some interest in connection with this article, since various authors have pointed to the weaker influence of Keynesian, interventionist economic policy in Finland than in Sweden during the period of the welfare state expansion (Pekkarinen /Vartiainen 1993; Kosonen 1987). Explaining this type of difference, among others, by the continuously weaker position of the political left in Finland, as compared to Sweden, Kosonen (1987; 1998; cf. also Julkunen 1991; Anttonen / Sipilä 1992) has claimed that in Finland, what he calls a “bourgeois mode of action” over time had come to be embraced, or at least accepted, by the different classes and parties as a “frame” which limits the political alternatives that are considered at any given point in time. This mode of action, according to Kosonen (ibid.), has meant that Finnish welfare policy has always been subordinated to the ultimate goals of economic growth and international competitiveness. Spending on welfare policies has been viewed as using an available economic surplus which has had to be adjusted to the available means and directed at stimulating further economic growth (cf. Julkunen 2001).

In Sweden, on the other hand, the traditionally strong position of the Social Democrats seems to have resulted in the emergence of a “Social Democratic hegemonic project”, in which the values of equality, solidarity and full employment were seen as goals in themselves, which constituted the basis for policy-making (Kosonen ibid.). Although not all authors agree that the values dominating (the thinking on) welfare policy in Sweden necessarily are in themselves social-democratic (cf. Esping-Andersen 1988; Heclo/Madsen 1987), many authors agree upon the traditionally-dominating role of the named values in Sweden.

Such claimed differences in the “wider frames” guiding the thinking on the role of welfare policy between Sweden and Finland could perhaps be reflected, among others, as differences in references made to structural/economic goals when discussing issues of social security and perhaps in less pronounced ideological differences in Finland (Kroll et al. 2000). This, at the same time, points to a complicated relationship between ideological and structural factors, which must be taken into account when results on justifications are interpreted.

Notwithstanding these kinds of differences in emphasis in the role of welfare policies as a part of the overall political strategy between the individual Nordic countries, Kosonen (1988, 104ff; cf. also Kautto et al. 1999, 13-14; Kvist 2001, 24) has identified a common "normative heritage". This encompasses a set of unifying policy goals behind the “Nordic welfare model”, institutionalised in the decades after WWII, functioning as a convention or unspoken agreement when choosing policy alternatives. These goals, which are considered here as (further) indicators of the “welfare state ideology”, are:

· universal social rights, or the notion that every resident of a country, regardless of civil status, is entitled to individual income security and welfare services;

· public responsibility to guarantee the welfare of all, which can be seen by the important role played by the public sector, both as regards social insurance as well as services;

· equality, both as regards the distribution of income and gender relations; and

· full employment, which there is some doubt as to how deeply this goal was ever embraced in Finland and Denmark.

If there are assumptions about the Nordic welfare model as being a “thinner layer” in the dominating overall policy paradigm in Finland, as compared to Sweden during the period of welfare state expansion, there have, on the other hand, been estimations presented that the ideological critique of the welfare state has never become as ideologically outspoken in Finland (Raunio 1995; Julkunen 2001; however, cf. Eitrheim /Kuhnle 2000 for an opposite view). In Sweden, various new political ideologies, mainly in the form of neo-liberalism had become more common already in the 1980s and early 90s (Boréus 1997; Svallfors 1996).

Although the wishes for an anewed de-politisation of welfare tasks are by many considered mainly neo-liberal, especially concerning issues of social security, they are shared by different political (and economic) schools of thought and will therefore be summarised under the heading of “welfare pluralism” (e.g. Ervasti 1996). This critique of the “welfare state ideology” has included moral concerns as well as economically-oriented arguments. Thus, a broad responsibility of the public sector for social security, services and employment has, on the one hand, been thought to reduce the capability of individuals to take responsibility for their own lives and to weaken social ties. On the other hand, it has been claimed that the taxes required for such a system, as well as the transfers and regulations of the labour-market, have reduced the incentives to work as well as the demand for labour and, thus, has resulted in higher unemployment. Therefore, it has often been said that the state should only provide “basic” security, while other welfare tasks should be transferred to the market and non-profit sectors (Boréus 1994; Stråth 2000; Ganßmann 2000; Sjöberg /Bäckman 2001).

As pointed out in the introduction, so far there is little (comparative) empirical evidence of the relative strength(ening) of such a “pluralist” paradigm competing with the “welfare state”, as regards the justification for stands on social insurance in the two countries.

4 Different levels of change in the social insurance system

Turning to the issue of how to discern between different levels of (suggested) change in the social insurance system while separating them from the causes for (the justifications used to legitimise them) this change, the main question becomes what kind of measure should be regarded as a change of the most profound sort (or “third order”) concerning a certain policy area. Here, the classification of social insurance institutions into ideal-types, based on programme characteristics, as presented by Korpi and Palme (1998), offers a fruitful starting point. Departing from a set of characteristics typical for two major social insurance programmes (old-age pensions and sickness cash benefits) in Western countries, Korpi and Palme (ibid., 666) identify five ideal-typical models of social insurance institutions, namely the 1) Targeted, 2) Voluntary state-subsidised, 3) Corporatist, 4) Basic security and 5) Encompassing models.

In the present context we must limit the analyses to the question of whether (suggested) changes in a programme are in accordance with the ideal type said to be characteristic of the Nordic social insurance system. On the basis of data for 18 OECD countries in 1985, Korpi and Palme (ibid., 670) find systems matching the characteristics of the Encompassing model in Finland, Norway and Sweden. The classification principles used are eligibility criteria, principles to define benefits and type of programme governance. In its ideal form, this model, a trimmed combination of the basic security and corporatist models, guarantees basic security for all in combination with homogeneous income-related benefits for the economically active, and the system is administered through public authorities. Thus, these characteristics could be used to discern whether a change would mean a deviation from the traditional, basic features of the social insurance systems in our two countries, and, thus, whether it constitutes a “third order” change in a system.

However, what has to be taken into consideration when analysing the discussion on social security is that, although exemplifying cases of the Encompassing model in the real world, the social insurance programmes included in this study do not necessarily (any longer) meet (all) the requirements of this ideal model.

Whether the reforms that have been carried through in most programmes during the last decade are to be regarded as changes merely in degree or as principle changes, has been a matter of debate (and has, among other things, led to the diverging views on the development referred to above). The fact that not all programmes have ever met all the above criteria, and that they have also been subject to changes during our period of investigation, leads to the conclusion that in our study, focusing on demands for changes in programmes that have been put forward, demands must be compared with the actual situation in which the statement is made.

Turning the question of what should be regarded as first and second order changes in a social insurance system respectively, it seems as if prior adaptations of Halls’ framework to social policies (see Nordlund 2000; Palier 2000) have used somewhat varying criteria. With reference to Hall’s own division, however, it seems that any kind of minor change in existing programmes, be they changes in levels of benefits, entitlement rules or other alterations, could be regarded as first order changes, while changes in the kind of policy instruments used (e.g. a replacement of one programme by another), as well as larger changes in existing programmes, which do not affect the basic principles of the Encompassing model (cf. the characteristics listed above), should be regarded as second-order changes.

5 Questions at hand, data and methods used

Based on the reasoning in Sections 2 and 3, regarding, on the one hand, a separation between different orders of change in the social insurance system, and, on the other hand, a separation between the suggested changes and what justifications are used in connection with them, we will make several observations. Firstly, we will analyse single statements in the Swedish and Finnish press, with a focus on suggestions of different orders of change in the social insurance system in the respective country at three points in time. Secondly, we will compare how these different orders of retrenchment, on an aggregated level, are linked to different types of justification. We will also investigate the role of different types of actors in the discussion.

The data used are based on the contents of all news articles, editorials and contributions to the debate dealing with issues of social insurance, published in five Swedish and seven Finnish morning news papers and tabloids during the month of January, in the years 1987, 1993 and 1997. The first point in time chosen represents the situation before the economic depression of the first half of the 90s. By including material from 1993, the aim is to get a picture of the discussion in the midst of the depression, during a time of very high employment rates and negative growth, while 1997 was chosen to represent the time when the countries can be considered to have recovered from the economic depression.

This data constitutes part of a larger database gathered by a project studying changes in various aspects of social policy in these countries. The choice of only certain periods in time, instead of including all material on social policy, is explained by practical reasons, i.e. the vast amount of material on social policy published in the press every year.

However, tests made to replace the months included by another month in the same year have shown that results on variables similar to those central to our study were not altered by this fact to any considerable degree (see Svallfors 1995; 1996). This fact can be assumed to be related to the nature of our variables, measuring at a general level the dominating views/stands of the different actors taking part in the discussion on the desired development of social insurance at a certain point in time. Such fundamental stands can be expected not to vary dramatically, according to which actual programme(s) that is/are discussed the most.

The newspapers included are selected to represent different political stands.[3] By including a broad selection of papers, the aim was to minimise the risk for biases in the discussion due to the selection of newspapers. Despite this, we have chosen to focus on comparisons of trends in the respective countries, rather than to compare distributions on single variables.

In addition, we have focused on analysing the single statements made/reported in the press, as opposed to discerning the dominating view in every article (which might contain many single and diverging statements). Thus, the data consist of a total of 663 statements concerning social insurance, out of which 380 from the Swedish and 283 from the Finnish press.

Although it may be assumed that the media to a certain extent, may affect statements made by other actors, for example, through the way they are depicted (Asp, 1986), it seems unlikely that the media would be able to decide over the content of single statements to such a degree that it is not at all possible to discern the problem definitions of those being interviewed or cited. It has also been shown that different actors are able to use the media to promote their own views (Mancini 1993; Katz 1992) and, because of this, the media today is often regarded both as an independent societal actor and as a platform used by other societal actors (Peterson /Carlberg, 1990).

In this study, the discussion of “social security”, on the one hand, is taken to mean issues related to any or all of the three single most important social insurance programmes (i.e., those related to old age, sickness or unemployment)[4] and, on the other hand, to statements dealing with the social insurance system in general.

Since we are interested in general positions and trends concerning a priori defined issues, quantitative content analysis (Krippendorff 1980; Bergström /Boréus 2000), which allows for generalisations to the widest possible extent, was considered the most suitable methodological choice. Variations of this method have been applied earlier in similar circumstances in a Nordic context (Boréus 1994; 1997, Svallfors 1995; 1996, Blomberg 1999). The variables used in our analysis, which are based on the discussion in Sections 2 and 3, are presented below and in Appendix 1.

In order to measure the extent of suggested changes, every statement has been encoded (twice, to maximise validity and reliability) according to its effect in relation to the presently existing system of social insurance.[5] Here we have made a division between 1)statements which suggest or merely demand an adjustment of the system, either “upwards” or “downwards, to indicate wishes of change of the first order. Since many statements during the 90s can also be expected to aim at preserving the system unchanged, we have chosen to classify this type of statement into a separate category. Statements in which demands/suggestions are put forward for 2)more substantial alterations in/of the present system have been encoded as second order changes. Statements that include propositions for changes that are 3)not in compliance with (meaning a further step away from)[6] the criteria characterising the Encompassing model are classified as third order changes. Statements on social insurance issues that do not take a stand as regards the development of the system or statements that are vague or ambiguous have been encoded into a separate category. Further, every statement has also been coded according to the type of justification presented for the suggested change. A division has been made between justifications referring to 1) the welfare state ideology, 2) welfare pluralism and 3)structural conditions.[7] The statements have further been encoded according to the type of actor. Here, the classification is based on previous similar studies (Svallfors 1996; Blomberg 1999).

6 Results

First, let us look at how questioned the social insurance system has been in Sweden and Finland, when discerning between different magnitudes or orders of suggested changes.

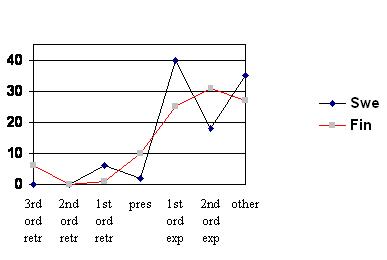

If we begin the analysis of the discussion in the Swedish press by looking at statements concerning social insurance in 1987, we find statements containing suggestions of different orders of retrenchment to be almost totally absent. Instead, it is common to suggest an expansion of the social insurance system of the first and second orders.

Figure 1. Suggestions of policy changes of different orders in the Swedish and Finnish debates on social insurance in 1987 (Values are in percentages)

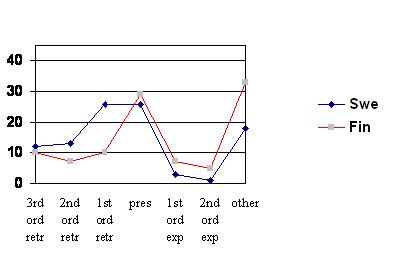

Figure 2. Suggestions of policy changes of different orders in the Swedish and Finnish debates on social insurance in 1993. Values are in percentages.

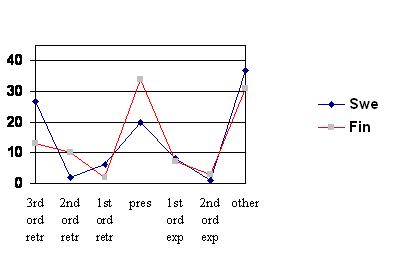

Figure 3. Suggestions of policy changes of different order in the Swedish and Finnish debates on social insurance in 1997. Values are in percentages.

In 1993 and 1997 the suggestions look very different, compared to 1987. Whereas statements suggesting an expansion of the system of the first and second orders were almost totally dominating in relation to the opposite view in 1987, the picture is inverted in the 1990s, with almost no actors speaking in favour of an expansion of the system. Instead, in 1993 wishes for an expansion have been replaced by wishes for retrenchment of the first (26% of statements), second (13%) and even third (12%) orders. At the same time, a new category has now appeared, which is made up of those speaking in favour of a preservation of the existing system(s).

In 1997, the share of actors speaking in favour of retrenchments of the first and second orders has again become very small. However, suggestions of retrenchment of the third order (that is, reforms not in compliance with the characteristics of the Encompassing model) constitute 27% of the total data. The share speaking in favour of a preservation of the present system still constitutes a significant group in 1997.

A comparison of Figures 1-3, over the time-span investigated, points to a rising share of suggestions of retrenchment of the third order. While no such suggestions or demands are made in 1987, their proportion of the total number of statements is 12% in 1993, growing to 27% of all statements in 1997.

If we move on to look at statements in the Finnish press, we again find suggestions of expansions of the system of the first and second orders to be dominating in 1987. Turning to the data from the 1990s, a reduction of the share of suggestions for expansion of the system, similar to the one found in Sweden, can be detected. However, in Finland the proportion speaking in favour of a preservation of the existing system stands out as the largest, both in 1993 and in 1997.

As regards statements in favour of a retrenchment of the system, the share of proponents of measures of different orders of change is quite similar in the middle and towards the end of the 90s. In 1993, 10% of the statements propose changes of the first order, 7% second order changes and 10% favour changes of the third order. In 1997, the corresponding figures are 2, 10 and 13%.

A comparison of the figures for Finland (Figures 1-3) indicates that the share of statements speaking for the most fundamental type of reform (third order changes), has increased somewhat over the time-span, being 6% in 1987, 10% in 1993 and 13% in 1997.

As can further be seen from Figures 1-3, about 1/3 of the statements each year, both in Sweden and in Finland, are descriptive or deal with aspects of social insurance other than those in focus here. However, they are included in order to illustrate the character of the discussion on social insurance in its entirety, and in order to get a picture of the relative number of statements in the press proposing retrenchments (or an expansion) of the existing system of social insurance. (This is also the case in Table 1 below).

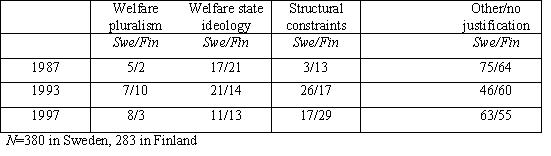

If we now turn to investigate the different types of justification presented in connection with the statements made, and begin by looking at the distribution of different justifications per se (Table 1), we find that in the Swedish material it is not possible to discern any clear change over time in the number of arguments that can be characterised as “welfare pluralist”. In every year studied, only 5-8% of the statements can be characterised as not commensurable with the normative basis of the Nordic welfare model. However, arguments based on “welfare state ideology” have become somewhat less common over the time-span, while statements based on ”purely” structural motivations are used more often during the 90s as compared to 1987.

A fairly similar pattern can be discerned in Finland. Justifications based on “welfare state ideology” have declined somewhat in number in the 90s; a critique based on “welfare pluralism” is put forward relatively seldom; and this type of justification has not increased notably during this period. Instead, a reference to “purely” structural justifications has become more common over time.

Table 1: Different types of justification in the Finnish and Swedish debates on social insurance 1987-1997 (Values are in percentages)

Thus, a comparison of the discussion in the two countries, in the light of the two variables presented above, reveals a generally similar “pattern” of rhetoric (and changes in it) in the two countries. The clearest difference between the countries is found on the variable measuring changes of the third order (cf. Figures 1-3). Whereas the proportion of statements speaking for the most fundamental type of reform is more or less identical in the two countries in 1987 and 1993, it is considerably higher in Sweden in 1997.

How, then, are suggestions of different orders of retrenchment linked, on an aggregated level, to the different types of justification identified? Since statements suggesting a retrenchment in the social insurance system were almost totally absent in 1987, we will only look at the data from the 90s.

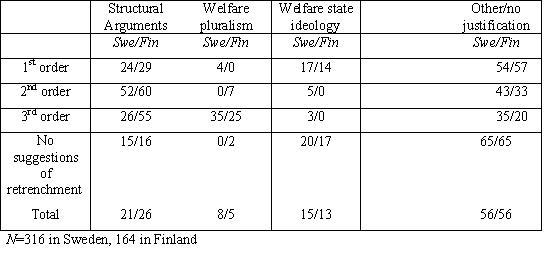

Table 2: Justifications behind suggestions of retrenchment of different orders in social insurance in Sweden and Finland in the 1990s. Values are in percentages

Our results, presented in Table 2, show that retrenchments of the first order are justified by referring to structural conditions and also to some extent by referring to the ”welfare state ideology”. Second order changes are justified by referring to structural conditions. Third order changes are justified by referring to either structural conditions or to “welfare pluralism”. This pattern can be discerned in both countries, although it is more common in Finland to justify even third order changes in terms of structural constraints.

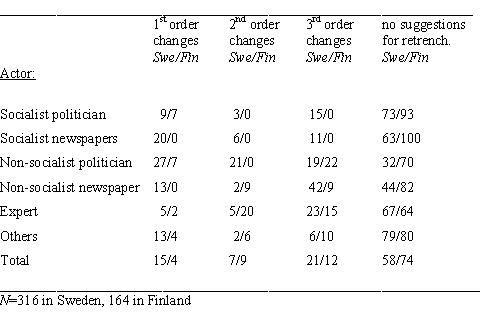

Table 3: Different actors’ suggestions of retrenchment in the social insurance system in Sweden and Finland in the 1990s (Values are in percentages)

Which, then, are the main groups of actors that suggest retrenchments in the system of social insurance? The results presented in Table 3 show that in Sweden the “driving forces” behind first and second order changes have been non-socialist politicians, while the non-socialist newspapers (e.g. in the form of editorials), above all, are suggesting third order changes. By looking at which actors have been the ones most reluctant to suggest retrenchments of any order, the picture concerning the advocates of retrenchment can be completed. As can be seen in Table 3, Swedish socialist politicians, followed by the socialist press and the group of “experts”, are the ones who have been most reluctant to suggest any retrenchments. In contrast, only one-third of the non-socialist politicians and about half of the statements by the non-socialist newspapers are not suggesting any retrenchments. For Finland, our results show lesser differences in this respect, mainly between politicians of different “colours”. Instead, it is the category of “experts” that is most inclined to suggest different orders of retrenchment.

7 Conclusions and discussion

The answer concerning how questioned, at a rhetorical level, the system of social insurance has been in the two countries during the period investigated, is that the number of voices demanding a “retrenchment” of the welfare state did become greater during the 1990s. At the same time, the share speaking in favour of a preservation of the existing system also is significant. Further, the almost total absence of suggestions of any retrenchments in the data from 1987 is worth noticing. The fact that suggestions that would mean a retrenchment of the first or second order are presented mainly in the midst of the deepest depression, is of course not a very surprising result, given the structural circumstances at the time. What is probably most interesting is that the share of suggestions of third order changes, did not decrease between 1993 and 1997. Instead, in Sweden suggestions of third order changes became even more common after the depression. These results indicate that dramatic changes in structural conditions were needed to trigger a broader public debate about retrenchment in social insurance programmes. But also, as assumed by Heikkilä et al. (1999), it is as if the new conditions that arose created a still existing potential for (demands of) welfare reform. At least where the pensions system is concerned, this assumption is supported by policy proposals presented in the last years both in Sweden and in Finland (like in many other European countries) regarding a limitation of the responsibilities of the state at the expense of the individual (Laitinen-Kuikka 2002; cf. also Hindrich /Kangas 2003, 588-589).

However, even though suggestions of different orders of retrenchment appear in the 1990s, our results, showing a relatively small share of explicitly-ideological justifications for the suggested retrenchment measures, do not point to any “wave” of explicitly-ideological attack on the system of social security. But, on the other hand, our results point at a certain decrease in the 90’s in the number of justifications based on the goals of the Nordic welfare model paradigm. This seems to indicate that other policy goals than the traditional are given priority by members of the societal elites.

The above findings taken together may help illuminate one possible reason for the contradictory opinions among researchers mentioned above regarding how questioned the welfare system has been in our two countries during the last decades.

Turning to an examination of the relationship between a suggested order of change and the type of justification presented for it, results for the 90s showed that suggestions of first order retrenchments were mainly justified by referring to structural conditions, and also to some extent by referring to the “welfare state ideology”. The latter type of reasoning is in line with the assumptions presented by some researchers (e.g. Heikkilä 1997), according to which not all elite groups favoured retrenchments in order to change the normative basis of the system, but rather to secure the preservation of it.

Second order changes in turn, are mainly justified by referring to structural constraints. Concerning third order changes, we can identify two main types of justification: on the one hand, those linked to (welfare pluralist) normative considerations and, on the other, references to structural constraints.

However, with reference to the discussion above on the relationship between structural and ideological factors, it remains uncertain whether and to what extent the increased proportion of references to “structural” arguments in the 90s should be interpreted as an indication of a change in the idea of what the welfare state is and what the goals behind it are. In other words, to what extent are the results of a growing number of references to “structural realities” (e.g. public deficits and/or demographic challenges, new international economic conditions) to be regarded as a sign of new goals being prioritised by members of elite groups at the expense of traditional social policy goals? And to what degree should such changes be separated from an ideological/ideational change? To what extent could they perhaps be assumed to be used by actors, instead of more explicitly-ideological arguments perhaps believed to be more controversial?

Could it be the case, that the relatively frequent references to structural conditions in connection with more radical alterations of the system are used because they are believed to be regarded as less controversial by the general public who has been showing a continuously strong support for the traditional goals (justifications for) and means (policy programmes) of the Nordic welfare model (e.g. Svallfors /Taylor-Gooby 1999)? Although the study cannot provide the precise answer to this question, it points to the important position of this type of justification for retrenchments in the debate on social insurance in the 90s in both countries. From a democratic point of view, this fact might be considered as problematic – even deep-cutting reforms are being proposed without touching on their normative implications.

To conclude our study, a few more general reflections on the type of approach used here will be discussed. Firstly, the points of view that are presented in the press obviously constitute only part of the total public discussion on the welfare state, and other “sources”, such as party programmes, might give another picture of the state of affairs. While such studies can provide information on (perhaps dominant) ideas within a certain elite, they cannot capture a picture of the scope of the discussion as a whole. To investigate the public discussion, as presented in the press, might be relevant because of its commonly-assumed effects both on citizens at large and on influential elite groups in a longer perspective. Thus, the content of the press can be assumed both to mirror the public discussion and to contribute to its future development.

Secondly, our study points in the direction of clearly ideational/ideological justifications being used mainly in connection with third order changes in programmes, something which seems to be in line with the assumptions of Hall (1993, cf. Section 2 above). Nevertheless, it might also be taken to show that research on the factual changes in welfare policies could gain from analyses making connections between the different orders of change in policy programmes and turning justifications used in relation to these changes into an empirical question. In doing so, some potential problems could be addressed, connected with the approach by Hall, when applied on an analysis of changes in welfare policy. This is a policy field perhaps more complex when, e.g. policy goals are concerned than the economic policy-making used by Hall when developing his model. On the one hand, an a priori exclusion of the possibility of changes in the way of thinking on welfare policy in connection with smaller policy changes, is hereby not made, thus allowing for a more sensitive analysis of the reasons and possible effects of smaller changes. On the other hand, Hall’s view of third order changes as a combination of fundamental changes in policy programmes and ideological/ideational change might also lead to difficulties in interpreting connections between more profound policy changes and the justifications for them. Another consequence of the original view on (third order) changes might be that very few welfare reforms may seem to meet all the criteria with certainty, thus resulting in the general conclusion that carried trough reforms do not indicate any fundamental changes in the thinking on welfare policy.

Obviously, the detection of different orders of policy change is also dependent on exactly where and how the line is drawn between different orders of change in policy programmes (and between different types of justification). Thus, while for instance Nordlund (2000) in his Nordic study on welfare policy, did not detect any third order changes, a tentative application of the criteria used above, on reforms in social insurance programmes carried out in Sweden and Finland in the 1990s points to a (fairly) similar pattern in the two countries, including changes of all three orders. The differences in interpreting changes of the above kind seem to call for a further consideration of the motivations used when creating indicators of different orders of change.

Finally, a systematic, comparative analysis of policy change, that also takes into account the various actors advocating different orders of change, might contribute to the understanding of welfare state retrenchment. Our results for Sweden point to a clear dividing line between the actors in the socialistic and non-socialistic blocs concerning different suggestions of retrenchment in social insurance programmes in the 90s. This could possibly be interpreted in terms of the Swedish political Right taking advantage of the depression as a reason for advocating retrenchment on ideological grounds (although not always in clearly welfare pluralistic terms, cf. the discussion above). Such an interpretation would be in line with the pronounced ideological undertone said to have been characteristic for Swedish (welfare) politics (see section 3 above). Nevertheless, in Sweden, traditional politics (still) seem to matter, at least on the rhetorical level.

In Finland, the political Right does not seem to have reacted in precisely the same way as in Sweden. Here, the differences between actors of different political stands are less pronounced in the 90s. This result would seem to fit the characterisations of Finnish welfare politics, at least in some respects, as ideologically less divided due to similar (conservative) views on the relationship between the economy and the welfare state (Kettunen, 2001). This is a factor which is likely to affect views on policy measures in times like the one under investigation.

As far as different actors are concerned, it can further be noted that, at the level of public discussion, politicians as well as experts, mainly in the public employ, often do take a stand regarding retrenchments of all magnitudes. Thus, at least in issues of social insurance, small changes seem to be very much of an issue of public (political) debate in both countries. On the other hand, we can note a more pronounced role of the Swedish press in comparison to the Finnish in promoting (e.g. in editorials) third order policy changes. Taken together, our results point to the existence of various complex differences in the “logic” of (discussing) welfare policy change between the two countries investigated, which are in many other respects similar.

What, then, could be anticipated about the future of the Nordic welfare model in these countries? Our results showed that (demands for) fundamental changes in policy programmes did not decrease after the depression, and can therefore probably not be seen as a response to acute economic hardships. Further, an increased proportion over time of references to structural arguments and a decreased proportion of references to the welfare state ideology in justifying reforms were detected. Taken together, these changes indicate a weakening of the traditional welfare state paradigm concerning social security. With reference to some writings by Beck (1999) one could ask whether these countries’ institutions of social security are in process of becoming “Zombie-institutions” which prevail more due to institutional inertia than because of continued ideological commitment to them among influential societal elites (see also Julkunen 2000). This would imply that the future of the Nordic welfare model, in the long run, is to be regarded at least as uncertain.

References

Anttonen, A. and Sipilä, J. 1992: Julkinen, yhteisöllinen ja yksityinen sosiaalipolitiikassa – Sosiaalipalvelujen toimijat ja uudenlaiset yhteensovittamisen strategiat [The public, communitarian and private spheres in social policy – The actors providing social services and new strategies for their mutual adjustment], in: Riihinen, O. (ed.): Sosiaalipolitiikka 2017. Näkökulmia suomalaisen yhteiskunnan kehitykseen ja tulevaisuuteen, Juva: WSOY.

Anttonen, A. and Sipilä, J. 2000: Suomalaista sosiaalipolitiikkaa [Finnish social policy], Tampere: Vastapaino.

Araki, H. 2000: Ideas and Welfare: The Conservative Transformation of the British Pension Regime, in: Journal of Social Policy, 29 (4), pp. 599-622.

Asp, K. 1986: Mäktiga massmedier. Studier i politisk opinionsbildning [The powerful mass media. Studies in the formation of political opinions], Stockholm: Akademilitteratur.

Beck, U. 1999: Työyhteiskunnan tuolla puolen, [Beyond work society], in: Janus 3, pp. 257-266.

Bergmark, Å./Thorslund, M./Lindberg, E. 2000: Beyond benevolence – solidarity and welfare state transition in Sweden, in: International Journal of Social Welfare, 9 (4), pp. 238-249.

Bergström, G. and Boréus, K. 2000: Textens mening och makt: Metodbok i Samhällsvetenskaplig textanalys [The meaning and power of a text: Methods for studying texts within the social sciences], Lund: Studentlitteratur.

Blomberg, H. and Kroll, C. 1999: Who Wants to Preserve the ’Scandinavian Service State’? Attitudes among Citizens and Local Government Elites in Finland 1992-1996, in: Svallfors, S./Taylor-Gooby, P. (eds.): The End of the Welfare State? Responses to State Retrenchment, London: Routledge.

Blomberg H. 1999: Rättighet, belastning eller business? En analys av välfärdsservicen i pressen åren 1987, 1993 och 1997 [A right, a burden or a business? An analysis of the social- and health services in the press in the years 1987, 1993 and 1997]. SSKH Skrifter 9, Forskningsinstitutet, Svenska social- och kommunalhögskolan vid Helsingfors universitet. Helsingfors: Universitetstryckeriet.

Blomqvist, P. 2004: The Choice Revolution: Privatization of Swedish Welfare Services in the 1990s, in: Social Policy & Administration, 38 (2), pp. 139-155.

Boréus, K. 1994: Högervåg. Nyliberalism och kampen om språket i svensk offentlig debatt 1969-1989 [The Shift to the Right: Neo-liberalism in argumentation and language in the Swedish public debate 1969-1989], Stockholm: Tiden.

Boréus, K. 1997: The Shift to the Right: Neo-liberalism in argumentation and language in the Swedish public debate since 1969, in: European Journal of Political Research, 31, pp. 257-286.

Clayton, R. and Pontussen, J. 1998: Welfare-state retrenchment revisited: entitlement cuts, public sector restructuring, and inegalitarian trends in advanced capitalist societies, in: World Politics, 51(1), pp. 67-98.

Cox, H. 1998: The Consequences of Welfare Reform: How Conceptions of Social Rights are Changing, in: Journal of Social Policy, 27 (1), pp. 1-16.

Eitrheim. P. and Kuhnle, S. 2000: Nordic welfare states in the 1990s: institutional stability, signs of divergence, in Kuhnle, S. (ed.): Survival of the European Welfare State, London: Routledge.

Ervasti, H. 1996: Kenen vastuu? Tutkimuksia hyvinvointipluralismista legitimiteetin näkökulmasta [Whose responsibility? Studies on welfare pluralism from the perspective of legitimacy], STAKES, Tutkimuksia 62, Helsinki: Gummerus.

Esping-Andersen, G. 1988: Jämlikhet, effektivitet och makt. Socialdemokratisk välfärdspolitik [Equality, efficiency and power. Social democratic welfare policy], in: Misgeld, K./Molin, K./Åmark, K. (eds.): Socialdemokratins samhälle, Kristianstad: Tiden.

Esping-Andersen, G. 2002: Towards the Good Society, Once Again?, in: Esping-Andersen, G. (ed.): Why We Need a New Welfare State, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Forma, P. 1999: Interests, Institutions and the Welfare State. Studies on Public Opinion Towards the Welfare State, STAKES: Helsinki.

Ganßmann, H. 2000: Labour Market Flexibility, Social Protection and Unemployment, in: European Societies, 2(3), pp. 243-269.

Gough, I. 1979: The Political Economy of the Welfare State, London: Macmillan.

Hall, P. 1993: Policy Paradigms, Social Learning and the State. The Case of Economic Policymaking in Britain, in: Comparative Politics, 25, (3), pp. 275-296.

Heclo, H. and Madsen, H. 1987: Policy and Politics in Sweden: principled pragmatism, Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Heikkilä, M. 1997: Justifications for Cutbacks in the Area of Social Policy, in: Heikkilä, M./Uusitalo, H. (eds.): The Cost of Cuts. Studies on Cutbacks in Social Security and their Effects in the Finland of the 1990s, Helsinki: STAKES.

Heikkilä, M. and Hvinden, B. and Kautto, M. and Marklund, S. and Ploug, N. 1999: Conclusion: The Nordic model stands stable but on shaky ground, in: Kautto, M./Heikkilä, M./ Hvinden, B./ Marklund, S./Ploug, N. (eds.): Nordic Social Policy. Changing Welfare States, London: Routledge.

Hindrichs, K. and O. Kangas 2003: When Is a Change Big Enough to Be a System Shift? Small System-shifting Changes in German and Finnish Pension Policies, in: Social Policy & Administration, 37(6), pp. 573-591.

Huber, E. and Stephens 2002: Globalization, competitiveness, and the social democratic model, in: Social Policy and Society, 1 (1), pp. 47-57.

Hugemark, A. 1994: Den fängslande marknaden: ekonomiska experter om välfärdsstaten [The captivating market: economic experts on the welfare state], Lund: Arkiv.

Jaeger, M. and Kvist, M.J. 2003: Pressures on State Welfare in Post-industrial Societies: Is More or Less Better?, in: Social Policy & Administration, 37 (6), pp. 555-572.

Julkunen, R. 1991: Hyvinvointivaltion ja hyvinvointipluralismin ristiriidat [Conflicts between welfare state and welfare pluralism], in A-L. Matthies (ed.), Valtion varjossa. Helsinki: Sosiaaliturvan keskusliitto.

Julkunen, R. 2000:, Hyvinvointivaltion näkymä – zombiko? [The prospect of the welfare state – a zombie?], in: Sosiaaliturva 1/2000.

Julkunen, R. 2001: Suunnanmuutos. 1990-luvun sosiaalipoliittinen reformi Suomessa [The change in direction. The social policy reform of the 1990s in Finland], Tampere: Vastapaino.

Katz, E. 1992: The End of Journalism? Notes on Watching the War, in: Journal of Communication, 42, pp. 5-13.

Kautto, M. and Heikkilä, M. and Hvinden, B. and Marklund, S. and Ploug, N. (eds.): 1999: Nordic Social Policy. Changing Welfare States, London: Routledge.

Kautto, M. 2001: Diversity among Welfare States. Comparative Studies on Welfare Adjustment in Nordic Countries, STAKES Research Report 118. Saarijärvi: Gummerus.

Katz, E. 1992: The End of Journalism? Notes on Watching the War, in: Journal of Communication, 42, pp. 5-13.

Kettunen, P. 2001: “The Nordic Welfare State in Finland”, in: Scandinavian Journal of History, 26, pp. 225-248.

Korpi, W. and Palme, J. 1998: The Paradox of Redistribution and Strategies of Equality: welfare state institutions, inequality, and poverty in the western countries, in: American Sociological Review, 63 pp., 661-687.

Kosonen, P. 1987: Hyvinvointivaltion haasteet ja pohjoismaiset mallit [The challenges for the welfare state and the Nordic models], Tampere: Vastapaino.

Kosonen, P. 1998: Pohjoismaiset mallit murroksessa [The Nordic models in transition], Tampere: Vastapaino.

Krippendorf, K. 1980: Content analysis. An introduction to its methodology. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications.

Kroll, C. and Blomberg, H. and Svallfors, S. 2000: Konjunkturernas offer eller godissamhällets verktyg? [Victim of the depression or tool of the ”Candy society”?], in: Socialvetenskaplig Tidskrift, 7( 3), pp. 244-266.

Kroll, C. 2004: Odemokratisk jämlikhet och orättvisa pålagor. Välfärdsservicen i svenska och finländska kommuntidningar 1985-2001 [Undemocratic equality and unfair burdens], in: Blomberg, H./Kroll, C./Lundström, T./Swärd, H. (eds.): Sociala problem och socialpolitik i massmedier, Lund: Studentlitteratur.

Kvist, J. 2000: Welfare Reform in the Nordic Countries in the 1990’s: using fuzzy-set theory to assess conformity to ideal types, Journal of European Social Policy, 9(3), pp. 231-252.

Laitinen-Kuikka, S. 2002: Avoimen koordinaation menetelmän soveltaminen eläkepolitiikassa [The application of the method of open coordination to pension policy], in: Saari, J. (ed.): Euroopan sosiaalinen malli. Sosiaalipoliittinen näkökulma Euroopan integraatioon, Helsinki: Sosiaali- ja terveysturvan keskusliitto ry.

Lehtonen, H. 2000: Voiko suomalainen hyvinvointivaltiomalli muuttua? [Can there be a change of the Finnish welfare state model?], in: Sosiologia, 37 (2), pp. 130-141.

Lehtonen, H. and Aho, S. 2000: Hyvinvointivaltion leikkausten uudelleenarviointia – Muuttivatko leikkaukset suomalaista hyvinvointivaltiota? [Re-evaluation of the welfare state cuts of the 1990s], Janus, 8 (2), pp. 97-113.

Lindbom, A. 2001: Dismantling the social democratic welfare model? Has the Swedish welfare state lost its defining characteristics?, in: Scandinavian Political Studies, 24 (3), pp. 171-193.

Mancini, P. 1993: Between Trust and Suspicion: How Political Journalists Solve the Dilemma, in: European Journal of Communication, 8, pp. 33-51.

Nordlund, A. 2000: Social policy in harsh times. Social security development in Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden during the 1980s and 1990s, in: International Journal of Social Welfare, 9, pp. 31-42.

Palier, B. 2000: Defrosting the French Welfare State, in: Ferrera, M. /Rhodes, M (eds.): Recasting European Welfare States, London: Frank Cass.

Pekkarinen, J. 1992: Keynesiläinen hyvinvointivaltio kritiikin vastatuulessa [The Keynesian welfare state in headwind], in: Riihinen, O. (ed).: Sosiaalipolitiikka 2017. Näkökulmia suomalaisen yhteiskunnan kehitykseen ja tulevaisuuteen, Juva: WSOY.

Pekkarinen, J. and Vartiainen, J. 1993: Suomen talouspolitiikan pitkä linja [The long-term line of Finnish economic policy], Porvoo: WSOY.

Peterson, O. and Carlberg, I. 1990: Makten över tanken [The power over thought], Stockholm: Carlssons.

Raunio, K. 1995: Sosiaalipolitiikan lähtökohdat [The basis of social policy], Tampere: Gaudeamus.

Sjöberg, O. and Bäckman, O. 2001: Incitament och arbetsutbud – En diskussion och kunskapsöversikt [Incentives and labour supply – A discussion and review], in: Frizell, J./Palme, J. (eds.: Välfärdens finansiering och fördelning, SOU 2001, 57, pp. 251-318.

Stråth, B. 2000: After Full Employment. European Discourses on Work and Flexibility, Brussels: P.I.E.-Peter Lang.

Sunesson, S. and Blomberg, S. and Edebalk, P.G. and Harryson, L. and Magnusson, J. and Meeuwisse, A. and Peterson, J. and Salonen, T. 1998: The flight from universalism, in: Journal of European Social Work, 1(1), pp. 19-29.

Svallfors, S. 1995: Välfärdsstaten i pressen. En analys av svensk tidningsrapportering om välfärdspolitik 1969-1993 [The welfare state in the press. An analysis of Swedish newspaper reporting on welfare policy 1969-1993], Umeå: Umeå Studies in Sociology no 108.

Svallfors, S. 1996: Välfärdsstatens moraliska ekonomi. Välfärdsopinionen i 90-talets Sverige [The moral economy of the welfare state. Opinions on welfare in Sweden in the 90’s], Umeå: Boréa.

Svallfors, S. and Taylor-Gooby, P. (eds.) 1999: The End of the Welfare State? Responses to State Retrenchment, London: Routledge.

Uusitalo, H. 1984: Comparative Research on the Determinants of the Welfare State: the State of the Art, in: European Journal of Political Research, 12, pp. 403-422.

Appendix 1: Guidelines for encoding different levels of change and type of justification.

Different levels of change

Third order changes

· Suggestions for changes meaning a deviation (further away) from the Encompassing model:

· The eligibility criteria are changed – from citizenship + (previous) employment to something else

· The principles for defining benefits are changed – from flat-rate + income-related benefits to something else

· The type of programme governance is changed – from an administration through public authorities to something else

Second order changes

· New groups are excluded (in case of expansion: included in) from a social insurance scheme

· Eligibility criteria (e.g. waiting days) or benefit levels are tightened/ reduced (in case of expansion: made more generous/ increased) by at least 20 percent

· The share of contributions by the state/government for financing a social insurance programme is reduced(increased) by at least 20 percent

First order changes

· Adjustments in eligibility criteria, financing and/or benefit levels smaller than the above

Justifications

Welfare state ideology:

· Positive judgements about the goals, means and/or effects of the public social insurance system, e.g., public transfers are needed in order to guarantee an equal distribution (of income) and satisfaction of needs

· The state/government should have main responsibility for social security

· The social security of the individual is a societal problem that should be solved “collectively”

· Explicitly negative judgements about the goals, means and/or effects of private welfare arrangements, e.g., private arrangements lead to a “division of the population” or increased inequality

Welfare pluralism:

· Positive judgements about the goal, means and/or effects of private social insurance arrangements

· Positive judgements about selective/means-tested public welfare policies

· The individual has got the main responsibility for his/her social security

· The social security of the individual is the individual’s own problem and should thus be solved by the individual him/herself

· Explicitly negative judgements about the goals, means and/or effects of the (present) public social security system, e.g., public social insurance results in a dependency culture.

· Structural constraints:

o Demographic constraints require changes in the social insurance system

o Economic constraints (budget deficits etc.) require changes in the social insurance system

o A positive development in the labour market/economy/industry requires changes in the social insurance system

Author’s

address:

Prof Dr Helena Blomberg / M Soc Sc Christian

Kroll

University of Helsinki,

Swedish School of Social Science, Research Institute

Pohjoinen Hesperiankatu 15 A

P.O.Box 16

FI-00014 University of Helsinki

Tel.: +358 9 191 28461

Fax: +358 9 191 28430

E-mail: helena.blomberg@Thelsinki.fi / christian.kroll@Thelsinki.fi