Position, Professional Expertise and Functions of an Educator of Child Care Homes in Lithuania[1]

Luidmila Rupsiene, Department of Social Pedagogy, Klaipėda University

Irena Leliugiene, Institute of Education, Kaunas Technological University.

1 Introduction

Speaking about professionals, working with children at child care homes in Lithuania, first of all we encounter a problem of terminology. This problem rises, because in various countries and languages we call these professionals differently. In Lithuania we call them ”auklėtojai”. We also use the word ”auklėtojas” when speaking about both professionals, working directly with children at kindergartens, and parents, as all parents are educators of their children. We suppose, that the word ”auklėtojas” corresponds to the German “erzieher”, and “auklėti” to “erziehen”. Every “auklėtojas” in Lithuania clearly realizes, that he is a pedagogue, because in this country every professional, involved in educational work with children – an ”auklėtojas”, a teacher, a social pedagogue and a special pedagogue – is called a pedagogue. In this context it is essential to conceive that in Lithuania an ”educator” and a ”social pedagogue” are different pedagogical professions and that none of the ”auklėtojas” identify himself as a social pedagogue.

The term ”educator” has not entirely assimilated into the Lithuanian language, however, it is wider and wider used in scientific literature. In our article we have chosen this term to refer to those professionals, who work directly with children at residential child care homes. As far as we could notice, in the English language these professionals are called “residential childcare workers”. However, in Lithuania a ”social worker” is a separate occupation, not pedagogical, though closely related to the occupation of the social pedagogue.

Here we have encountered another problem: terms (social) ”pedagogue, pedagogy, education, educator” are not identically understood in Lithuania, just like in other countries and languages, where they are used.

Wishing to emphasize that professionals, working at residential child care homes of Lithuania– ”auklėtojai”, first of all, carry out educational work, we decided, that the most precise translation into the English language would be ”educator” or ”pedagogue”. However, after we have found explanations that the term ”pedagogue” has not entirely assimilated into the English language, we decided to translate ”auklėtojai” as ”educators” anyway. So, in this article ”educator” – a professional, directly working with children at residential child care homes, is “auklėtojas” (in the Lithuanian language), “kinderheim erzieher” (in the German language), “residential childcare worker” (in the English language).

So far work of educators of child care homes (hereinafter in this article abbreviation of CCH is used) in Lithuania has been poorly investigated. And only recently the number of investigations in this field has increased. The greatest attention to this problem is paid in Braslauskienė’s doctoral thesis ”Peculiarities of education of children without families at care institutions (social and psychopedagogical aspect)”, defended in 2000. In scientific literature appear solitary articles by specialists of education science, sociologists and psychologists dedicated to the similar problems (Litvinienė, 1998; Raslavičienė, 1996, etc.). Some aspects of the problem are scrutinized in masters’ theses of Kaunas University of Technology, Klaipeda University, the Physical Culture Academy of Lithuania and Vilnius Pedagogical University (Eidejūtė, 2003; Jevaitytė, 2002; Kentraitė, 2003; Leiputė, 2000; Skališius, 1997; Svigarienė, 1996, Tamošiūnienė, 2003).

In her thesis Braslauskienė (2000) educed that in practice many educators of CCH can be characterized by:

· lack of expertise: many educators do not have enough pedagogical psychological knowledge, therefore they are not competent to solve problems they encounter at their work, and as a result create a formal, child unfriendly environment at their institutions;

· negative attitudes towards their pupils and alienation from children: many educators have negative attitudes towards their wards, therefore they fail to create a proper, family-like atmosphere at their institutions; children do not trust their pedagogues, they do not tend to talk to them about their experiences, are afraid to open up before their eyes, hide real causes of their fears or anxiety;

· application of physical and restrictive punishments: one fifth of educators beat children with a ruler, pull their ears, nip them, shake their shoulders, nearly two thirds use restrictive punishments (force children to their knees, make them stand with their arms held up, order them to do a great number of physical exercises, etc.);

· psychological tiredness: pedagogues are usually psychologically tired of frequent quarrels of children, their conflicts, vindictiveness and fights.

Litvinienė (1998) educed another peculiarity of educators’ work – at public child-care institutions educators tend to restrict natural self-expression of children. The scientist has come to this conclusion after observation of educators’ activity: in infants’ homes one – one and a half year old infants are kept in play-pens, where there is no enough space for them to move and research the world. The infants can not go where they want to, can not take toys they wish, because not all the toys are allowed to play with – some are intended just to feast eyes upon.

Skališius (1997) established, that educators of CCH have a rather poor influence on processes of children’s socialization: only 24 percent of the participants of his research answered that they were educators of CCH who had the greatest influence on their world outlook; only 30 percent acknowledged that they got information on sexual life issues from their educators; only 35 percent received spiritual support from their educators; only 23 percent tended to listen to advice of educators of CCH.

In Lithuania we desiderate researches, looking deeper into roles of educators of CCH, their professional requirements, functions, expertise. Such researches are especially urgent, because after restitution of statehood in care and education policy of Lithuania appeared new tendencies, raising new requirements to organization of child education and care. This reasoning encouraged us to choose a research p r o b l e m disclosing what professional requirements are raised to educators of CCH in Lithuania, what professional expertise and functions of the educators are.

The research o b j e c t is a position of an educator of CCH, his professional expertise and functions.

The research a i m is to investigate professional requirements to educators of CCH, their professional expertise and functions.

The research m e t h o d s are analysis of scientific literature and documents, empirical research. Analyzing scientific literature we tried to get acquainted with already discovered peculiarities of work of educators of CCH. Analyzing documents we tried to establish legal basis for work of educators of CCH. By empirical research we tried to find out how often educators carry out concrete functions, how the educators evaluate importance and problems of these functions, what problems are encountered while fulfilling the mentioned functions[2].

2 Child care homes as institutions for the care and education of children

Issues, related to educators’ work at CCH are to be investigated in the context of care and education policy, because CCH are institutions for the care and education of children.

In Lithuania, just like in other states, a number of children are deprived of care of their parents. According to data, possessed by the Department of Statistics of Lithuania (Children of Lithuania, 2001), every year the number of such children is increasing by about 3 thousand: in 1998 – by 3,502; in 1999 – by 3,261; in 2000 – by 2,597 (the total number of children in Lithuania at the beginning of 2001 was 876,847). The Department of Statistics of Lithuania, which has divided all the reasons of deprivation of the parents’ care into inevitable (death of the parents, enduring disease, parents are proclaimed to be unaccounted-for in the order, established by the law, etc.) and avoidable (asocial families, parents themselves reject their children, do not take care of them, commit acts of violence, etc.), established that institution of care was inevitable only in every fourth case of its provision for children, and that only one of ten children deprived of the parents’ care was an orphan. So, the main reason of deprivation of parents’ care is asociality of families.

During the late centuries destiny of children deprived of the parents’ care (especially orphans) has been causing worries of societies of all the European states: first of all, they were such children for whom care homes, where the children were supervised and educated, were established. Each state has already got a distinctive history of care institutions. After restitution of independence of Lithuania in 1991 experience of other lands was critically analyzed and an original care system was created. At present main child care issues are regulated by a new Civil Code, which came into force in 2001. Till then child care was regulated by other legal acts (for instance, Child care law, etc.), however, the latter became invalid as soon as the new Civil Code came into force, because their essential norms were transferred into the Code mentioned.

According to the tradition, prevalent in many states in the XX century, in Lithuania children deprived of the parents’ care usually were accommodated at close institutions: infants – at infants’ homes, children of preschool age – at children’s homes, children of school age – at boarding schools. Mass building of such institutions started just after the World War II, because quite a few children became orphans and the state assumed care for these children. Within forty years after the war the number of such institutions tripled, however, poorly satisfied needs of the society.

Recently in child care policy of Lithuania can be noticed a new tendency, anchored in the Civil Code, – a child deprived of the parents’ care is accommodated at a care institution only if there is no opportunity to take care of the child in a foster family or an extended foster family (the extended foster family is a care home of a family type, when having their own children families take care of several children deprived of the parents’ care). So, the child care policy gives priority to foster families. Every year since 1999 approximately half of children, deprived of parents’ care within the year, are settled in foster families. The number of extended foster families in the state is growing, but this form of care is not very popular: they are about 2% of homeless children, who are accommodated in extended foster families within a year (Children of Lithuania, 2001).

Another new trend in the child care policy is established by the Work and social research Institute that in 2001 carried out scientific research ”Analysis and evaluation of activity of institutions for the child care and special education of local governments and regions” and established, that a radical turn took place in the system of child-care institutions of Lithuania, namely, a social care became dominant. At the end of 2000 57 % of all the child care places in Lithuania were located at institutions, rendering social services (day-time care centres, temporary care groups and other non-stationary institutions), and 43 % – at institutions, rendering stationary services.

So, as it is becoming clear from this review, half of the children deprived of the care get into care homes. At present in Lithuania work CCH of various types: 5 infants’ homes (taking care of infants), 7 general education boarding schools, 55 special boarding schools, 4 special homes for the upbringing and care of children, 6 care homes for children with disabilities, 31 regional care homes, 20 child care homes under local governments, 47 child care groups under local governments, 14 non-governmental child care homes, 49 extended foster families, 17 temporary child care homes (Children of Lithuania, 2001).

In many care institutions of Lithuania children live, and children of school age study at the nearest schools together with other children of the settlement. Studying is organized only by special care institutions (for children with disabilities, special needs). Stationary Child Care Homes in the country are interpreted as a constituent of the social care and education system, therefore their activity is controlled by the Social Policy Department of the Ministry of education and science.

Stationary Public Child Care Homes base their activity on regulations, issued by the Minister of education and science in 1996. These regulations recognize that child care groups may include 7 to 12 children of the same or different ages. Children with developmental derangements may be educated in general groups. They are provided with corrective and special education. Children from one family are sent to the same care home, nearest to their place of residence (except cases, when any brother/sister needs special help). Children are accepted at care homes and leave them all year round according to the Mayor’s resolution.

Children from rural areas get into stationary child care homes more often than children from urban areas. According to data of Services on Protection of the Rights of the Child there are 60 thousand of problematic children in Lithuania. The number of problematic children and correspondingly the need for care is considerably higher with children from rural areas than from urban ones. According to data of the above mentioned scientific research by the Work and social research institute, 6.7 children up to 15 years old of 1,000 children living in the rural areas are cared of at Child Care Homes, while the corresponding number of such children for urban areas is 3.3 of 1,000.

A contingent of stationary child care homes is rather various. They are not only children deprived of the parents’ care who are patronized at child care homes. The number of children, getting there from problematic families due to poverty, is growing. Such children do not have any special needs and it would be better for them to be raised in their families, if their families received a sufficient support of the society.

On the other hand, almost none of the children, living and studying at boarding schools with the status of care homes, are deprived of the parents’ care. The boarding schools are intended for children from families requiring social support; that is why there are hardly any children deprived of the parents’ care there. Moreover, a great part of the contingent of the boarding schools is children from rather normal, but living in remote locations families. If the problem of riding these children to school was solved, the children could live in their families.

However, nevertheless the handsome majority of all the contingent of Child Care Homes is children deprived of the parents’ care. It is a specific children contingent. The major part of these children has experienced deep stresses, lived in inharmonious, conflicting families, under poor economic conditions.

Inmates of Children’s homes encounter more difficulties in cognitive development, experience emotional problems, feel psychologically unsafe, are badly socially adapted, their sexual identification process is slowed-down (Raslavičienė, 1996). As it is proved by various scientific researches (Braslauskienė, 2000), such children more than other their coevals tend to depressions, fears, aggression, some of them have psychical and physical disorders, special needs.

So, activity of CCH in Lithuania is altering together with changes taking place in the care and education policy. Since there are various structural types of CCH, we have chosen regional stationary CCH, where the majority of inmates are children deprived of the parents’ care, for the further research.

3 Educator is the essential position at child care homes

The position of an educator is recognized in the resolution of the Board of the Ministry of education and science of 1994. This resolution introduces several types of staff of CCH:

· top executives (the director, his deputies);

· pedagogical staff (educators=”auklėtojas”, a psychologist, a music adviser, a coach, a special pedagogue, a speech therapist);

· support pedagogical staff (assistant educators, a librarian);

· medical staff (a physician, nurses);

· support housekeeping staff (accountants, a secretary, storekeepers, linen supervisors, tailors, shoemakers, cooks, laundry workers, building supervisors and repairmen, drivers, building watchmen, hairdressers).

Educator is the essential position at CCH. While other employees, fulfilling their duties, may contact with children more or less often, educators are the people, who must be beside the children all the time, secure care for them and their education.

At present the position of educators of child care homes is not strictly regulated at the state level – every care home approves independently prepared duty regulations at the session of its Council of pedagogues. However, the State formulates some landmarks of work of pedagogues in the Resolution on Child Care Homes (1996). In the mentioned resolution it is stated, that all pedagogues of care homes must:

· search for certain forms and methods of pedagogical activity, consistent with contents of education and its alterations;

· prepare for additional education events and arrange them skillfully;

· help children to form foundations of moral, healthy lifestyle and personal hygiene;

· bring up children’s diligence, responsibility, confidence, initiative, self-dependence, exactingness to themselves;

· accumulate knowledge in the fields of pedagogy and psychology, improve their qualification and pass a certification according to the established order;

· keep within norms of general and pedagogical ethics;

· watch, analyze and correct influence of legal guardians, parents as well as social and cultural environment on education of the children;

· analyze their pedagogical activity, evaluate education results and introduce them to colleagues, legal guardians (parents), heads of child care homes;

· keep documents, related to their pedagogical activity.

However, there are some additional requirements, raised to group educators (to ”auklėtojas”):

· to get to know each child, his individuality well, to use the gained knowledge during the educational process;

· to form personal hygiene habits;

· to afford the child with clothes, footwear and other domestic commodities;

· to organize doing homework and encourage studying motivation;

· to organize children’s spare time, taking into consideration their inclinations and interests;

· to create a family-like living environment for children;

· to help children to orientate themselves in a social environment, to prepare them for integration into the society;

· to base work with children on principles of democracy and humanism.

As we can see, the requirements are formulated too generally, not paying much attention to specificity and problems of the contingent of Child Care Homes. It is notable that describing the position of an educator in the documents mentioned such functions as child care, protection and representation of rights the child are not mentioned at all. And CCH is intended not only to educate children, but also to take care of them.

In the Civil Code (2001) the aim of child care is formulated as guaranteeing child’s environment, where he could safely and properly grow, develop and improve. There are proclaimed the child care tasks as follows:

1. To appoint for a child a legal guardian, who would take care of him, bring him up, represent him and protect his rights and legitimate interests.

2. To create for a child living conditions, consistent with his age, health and development.

3. To prepare a child for self-dependent life in a family and society.

It is the staff of CCH, and first of all educators, who must realize this task and the objectives. The educators’ role is the most significant, because they spend the most time with children, educating and patronizing them.

According to data of the scientific research, carried out by Lithuanian Work and Social Research Institute (2001), the structure of the skeleton (working directly with children) staff of residential child care homes is not optimal in respect to problems and needs of children, living there. It is more oriented towards schooling and educating services, but not towards social work with children and families regarding their social problems.

In many European countries traditionally the main work with children at CCH is done by social pedagogues (Social education and social educational practice in the Nordic countries, 2003). Recently it is widely acknowledged that social education originates from child care homes. Social pedagogues of CCH are used to rendering socioeducational assistance to children, suffering due to abuse, importunity, neglect by their parents, children having various special needs due to physical and mental disorders, anorexia, delinquency, drug abuse, etc.). Such work requires special preparation in the field of social education/social pedagogy.

Analysis of foreign literature (Social education and social educational practice in the Nordic countries, 2003; Brannen and Moss, 2003; Bannon and Carter, 2003; etc.) and presented above analysis of Lithuanian documents assured us that the position of educators of CCH in Lithuania should be changed. The educator should take care of children’s social education.

The essential condition for educators’ activity should become creation of a family-like environment suitable for the child: which means that it is necessary to create living conditions, consistent with the child’s age, health and development.

Functions of educators could be determined, taking into account tasks and objectives of social education of children:

· representation of the child and protection of his rights;

· evaluation (getting to know each child well, evaluation of his individuality and need for help);

· supervision (watching the child in order to prevent him from harming himself or the others);

· provision (affording the patronized children with proper clothes, footwear, domestic commodities, other material and spiritual values);

· teaching (organization of doing homework, help preparing for lessons, bringing up studying motivation);

· upbringing (help children to form foundations of moral, healthy lifestyle, personal hygiene, to bring up children’s diligence, responsibility, confidence, initiative, self-dependence, exactingness to themselves);

· correction (watch, analyze and correct influence of legal guardians, parents as well as a social and cultural environment on education of the children);

· prophylactic - preventive (arrange prevention of delinquency, pernicious habits and drug addiction, other social diseases);

· organization of leisure time (taking into consideration children’s inclinations and interests, address them to additional education institutions, clubs, arrange various events and pithy children’s leisure time);

· preparation for life in a family;

· preparation for life in society (help to orientate in the social environment);

· pedagogical self-education (accumulate knowledge in the fields of pedagogy and psychology, improve their qualification and pass a certification according to the established order; search for certain forms and methods of pedagogical activity, consistent with contents of education and its alterations; evaluate education results and introduce them to colleagues, legal guardians (parents), heads of child care homes);

· keeping documents (keep documents, related to their pedagogical activity, according to the order, established at the institution);

· mediation (an educator is a mediator between the child and his teachers, medical personnel, other specialists, relatives, permanent and temporary legal guardians);

· consulting (consult children on various life issues, such as choice of profession, solving of conflicts, friendship, etc.).

The above mentioned tasks and objectives of social education should be taken into account when creating a new functional model of work of an educator of CCH.

So, as we can see from analysis of documents and scientific literature, the position of an educator has no distinctive definition at the state level, despite documents, regulating child care, and European experience in the field of organization of such work. It is necessary to change an attitude towards the position of educators of CCH and to determine its functional model anew, emphasizing tasks and objectives of social education of children.

4 Professional expertise of educators of child care homes

Educators (”auklėtojas”) are specially trained for work at child care homes at none of higher schools of the country. On the whole there is no conception of training of such specialists in Lithuania.

In the Child Care Home Regulations (1994) it is recognized, that they are persons with higher or high pedagogical education, who may work as educators (”auklėtojas”) of CCH. Therefore in fact they are teachers of various subjects, primary school teachers, teachers of children of preschool age and specialists with another pedagogical education, who work as educators. However, while doing their work educators (”auklėtojas”) must improve their qualification. Every educator passes a certification according to the order, established by the Ministry of education and science, and is given a corresponding qualification, such as one of an educator, a senior educator, an educator-methodologist or an educator-expert. The certification helps to solve a problem of filling gaps in the educators’ expertise: even an educator, who is very poorly prepared for the job, is forced to raise his qualification, so that he would get a higher educator’s category.

We have to admit such a fact of today that a competition to vacancies of educators (”auklėtojas”) of child care homes increases together with growing teachers’ unemployment. During a conversation with specialists of the Department of education we found out that candidates take active part in competitions for filling positions of educators, announced by the regional department of education recently. Among participants of the competition there are quite a few social workers, social pedagogues, primary school teachers and subject teachers with the master’s degree. Such competitions allow child care homes to choose good specialists and to direct competent pedagogues to work at child care homes.

During the empirical research we tried to evaluate a professional expertise of working educators (”auklėtojas”). We made our opinion about the professional expertise according to several characteristics as follows:

· education gained;

· degree and category of qualification;

· motivation of choosing work;

· emotional attitude towards one’s position;

· personal evaluation of one’s expertise;

· attitude towards Convention on the Rights of the Child.

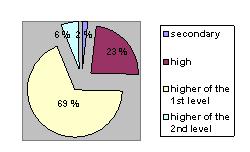

The handsome majority of educators (”auklėtojas”) of CCH have higher education of the first or the second level (67 and 6 percent correspondingly). However, approximately one fourth of educators have only high education, and some of them are studying at higher schools now (Figure 1).

According to the professional education gained at a higher school, a qualification of educators (”auklėtojas”) can be divided as follows: the majority of educators have a professional qualification of a teacher (biology, history, physical education, handicrafts, Lithuanian language and literature, Russian language and literature, mathematics, and most frequently – of a primary school) – 43 percent, of an educator (to be more precise – a teacher of children of preschool age) – 32 percent, of a social pedagogue or a social worker – 9 percent. Other educators (”auklėtojas”) have either not indicated their professional qualification at all or indicated, that they have a different professional education (8 percent), such as a technologist in light industry, a choreographer, a special pedagogue, etc.).

Figure 1: Education of the participants of the research

Although, as we can see, the handsome majority of educators (”auklėtojas”) did not gain a professional qualification of an educator (”auklėtojas”) within the period of their studies, with time passing they have deepened their expertise in the area of child upbringing and at present 63 percent of educators (”auklėtojas”) have a professional category of a senior educator, 14 percent – of an educator and 4 percent – of an educator – methodologist. None of the participants of the research has the highest professional category of an educator – expert.

We asked the educators to evaluate their professional expertise (knowledge, attitudes, proficiency and skills) at the beginning of work at CCH and now. 60 percent of the participants of the research evaluate their expertise at the beginning of work as middling. Even 21 percent think that they were very well prepared for the job; according to only 7 percent of educators, they were not prepared for the job and absolutely not competent. Evaluation of their present expertise is better: almost half of the participants of the research think their expertise is high and even very high. Only one person believes that his present expertise is scanty. All the others evaluate it as middling. So, these data show a general tendency as follows: expertise of educators grows together with seeking a higher category.

A motivation of a choice of the profession of the majority of educators (”auklėtojas”) is very positive: even 49 percent of the respondents state that work of an educator of CCH is their vocation, that they have chosen this work consciously, following an altruistic wish to help children deprived of the parents’ care. 36 percent of educators started working at CCH by accident, but do not regret about it at ll. However, work motivation of 15 percent of educators is very weak. They work as educators only because they have to earn their living, they would be glad to change their job, however fail to find a better one.

A motivation of choosing work is also related to an emotional attitude of educators (”auklėtojas”) towards their position. Since the motivation of most of the educators is positive, the majority (68 percent) are very pleased with their job. Emotional satisfaction of a quarter of the participants of the research (27 percent) is rather middling. Only a few persons are greatly dissatisfied with their position.

We can also come to certain conclusions about professional expertise of educators (”auklėtojas”) considering their attitude towards some most important documents, they should follow at their work. One of such essential documents is a Convention on the Rights of the Child. Unfortunately, only 43 percent of the participants of the research state that they follow the Convention in their everyday work. One third of the participants of the research (27 percent) have read this document at a library. A disturbing fact is that according to 17 percent of the participants of the research it is difficult to put the Convention on the Rights of the Child into practice at residential Child Care Homes.

So, the professional expertise of educators (”auklėtojas”) of CCH at the beginning of work is rather poor and, in fact, does not conform to tasks of social education of children. However, a positive motivation of choosing the work, a positive emotional attitude towards their work and the order of issues of pedagogues established in Lithuania constrain educators to improve their professional expertise. In educators’ opinion the present professional expertise is very high.

5 Work functions of educators of child care homes

Investigating educators’ (”auklėtojas”) work functions we analyzed how often educators carry out concrete functions, how the educators evaluate importance and problems of these functions and what problems are encountered while fulfilling the mentioned functions. Within the research we analyzed the functions, which should be carried out or are carried out by educators, in respect to tasks and objectives of social education of children, described in Section 2.

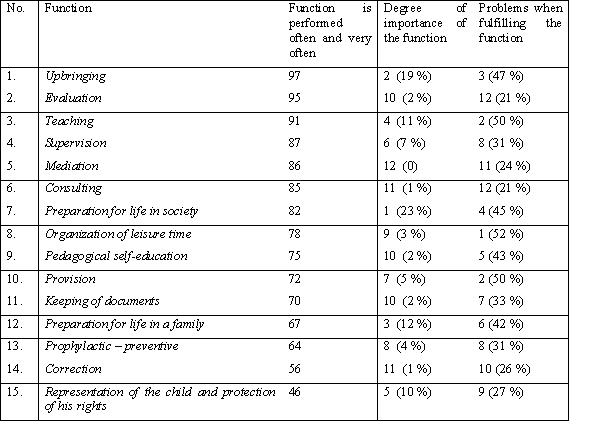

When analyzing data of the empirical research we became able to classify all functions of the educator according to the fact how often educators fulfil certain functions at their work (Table 1).

Table 1: Specificity of fulfillment of functions of educators of CCH

As we can see, at their work educators (”auklėtojas”) fulfil all functions we have indicated in Section 2 in respect to tasks and objectives of social education of children. The educators pay greatest attention to upbringing, evaluation and teaching of children. The educators pay quite a lot of attention to supervision of children, mediation, consulting, preparation for life in society and organization of leisure time. Rather often educators care for improvement of their expertise. The educators pay least attention to the function of representation and protection of the rights of the child: fewer than a half of the participants of the research state that they perform this function often and very often. The last-mentioned fact may be related to the attitude towards the Convention on the Rights of the Child discussed above. Collation of both these facts let us presume that on the whole educators of CCH pay too little attention to the rights of the child and protection of them.

It is understandable, that educators fulfil the functions demanded from them. However, it is also a personal educator’s attitude towards significance of the function that influences the way it is performed. After the investigation of educators’ opinion about this matter, it became possible for us to classify all the mentioned functions according to their importance (Table 1). A deeper analysis of the data, presented in Table 1, let us draw general conclusions as follows:

· An educators‘ opinion about significance of functions and the attention they pay to fulfillment of these functions at their work in reality substantially differ. According to the educators their most important functions should be preparation of children for life and family, upbringing, teaching and representation of children as well as protection of their rights.

· At the level, regulating activity of educators of CCH, not enough attention is paid to representation and protection of the rights of the child; therefore educators devote insufficient time to these functions in their activity.

· In educators’ opinion all the other functions, despite giving a great attention to them at direct work, are not essential.

· The educators consider a function of personal pedagogical self-education as absolutely non-essential. This conclusion is related to the above mentioned data on educators’ evaluation of their personal expertise, which is quite high. We can presume that the educators’ are satisfied with their professional expertise and do not see any necessity to improve it.

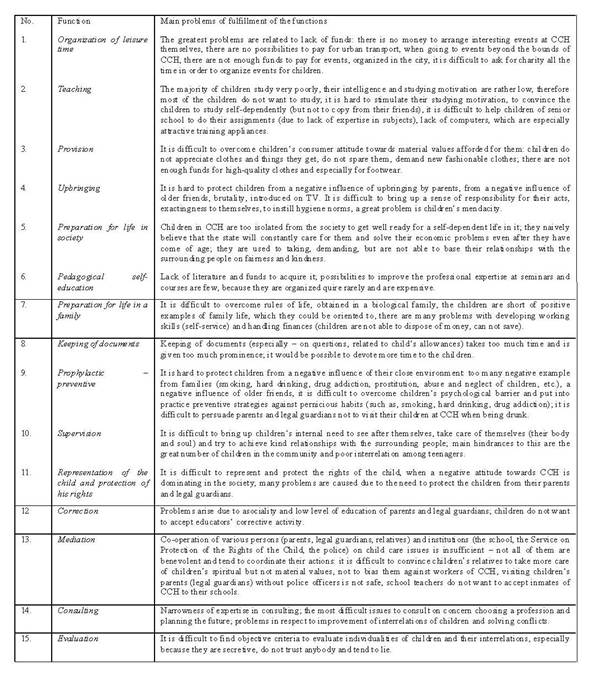

Trying to clarify problems, related to fulfillment of the functions, we asked the educators to indicate what problems they encounter with at their work when performing one function or the other. The results, presented in Table 1, show that most problems arise when fulfilling the functions as follows: organization of leisure time, teaching, provision and upbringing. The educators regard consulting, evaluation, mediation, correction, representation of the child and protection of his rights as the easiest. Problems, related to fulfillment of functions, are summarized and presented in Table 2.

Table 2: Problems, related to fulfillment of educators’ (”auklėtojas”) work functions

As it is seen from the analysis of fulfillment of educators’ functions, educators of CCH perform functions that more or less mirror tasks and objectives of social education of children. However, it is evident, that special socioeducational functions (such as, correction, prophylactic-preventive, representation and protection of the rights of the child, etc.), especially significant for the problematic contingent of CCH, are fulfilled insufficiently. The educators pay the greatest attention to the functions demanded from them. Therefore, aiming at better organization of social education of inmates of CCH, it is necessary to change a conception of the position of an educator and correspondingly – a professional functional model.

6 Conclusions

Investigating peculiarities of educators’ (”auklėtojas”) work at regional stationary child care homes, where the majority of inmates are children deprived of the parents’ care, we established that:

1. An activity of CCH is changing together with the care and education policy, where recently a conception of CCH as an institution for the care and education of children has been anchored.

2. The position of an educator of CCH is determined at the state level, however, quite vaguely, not highlighting significance of a social education of children.

3. The professional expertise of educators (”auklėtojas”) of CCH is distinguished by dynamism: rather poor at the beginning of educators’ work and rapidly growing with gaining experience.

4. Educators (”auklėtojas”) of CCH perform functions, which only partly mirror tasks and objectives of social education of children, groundlessly paying little attention to the functions, which could assist inmates of CCH to integrate into the society more successfully.

The research results encourage us to think that politicians, working in the field of child care and education, should pay more attention to organization of child care and education at child care homes. The position of the basic worker of CCH – an educator (”auklėtojas”) – should be determined more clearly. Following the mode of Western Europe it would be reasonable to replace the position of an educator by a position of a social pedagogue. A more definite functional model of this position, with goals of social education of the specific group of inmates of CCH highlighted, should be created. Educators (”auklėtojas”) of CCH should improve their expertise studying social pedagogy in consecutive and nonconsecutive study programs.

References

Brannen, J. and Moss, P. 2003 (eds.): Rethinking Children‘s Care, Buckingham/Philadelphia: Open University Press.

Braslauskienė, R. 2000: Bešeimių vaikų ugdymo ypatumai globos institucijose (socialinis ir psichopedagoginis aspektas), Daktaro disertacijos santrauka, Klaipėda: KU leidykla.

Lietuvos vaikai 2001: Vilnius: Statistikos departamentas prie Lietuvos respublikos vyriausybė Lietuvos Respublikos Civilinis kodeksas (2001), Vilnius: Saulužė.

Lietuvos Respublikos Švietimo ir mokslo ministro 1996 04 26 įsakymas Nr. 456 dėl Valstybinių globos namų.

Litvinienė, J. 1998: Ankstyvojo amžiaus vaiko saviraiška – socializavimosi šeimoje išdava. Socialinės grupės: raiška ir ypatumai. Vilnius: Lietuvos sociologų draugija, Lietuvos filosofijos ir sociologijos institutas, pp.331-350.

Bannon, M. and Carter Y.H. 2003 (eds.): Protecting Children From Abuse and Neglect in Primark Care, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Raslavičienė, G. 1996: Gyvenimo vaikų namuose įtaka auklėtinių psichinei ir socialinei gerovei. Lietuva socialinių pokyčių erdvėje, Vilnius: Lietuvos sociologų draugija, Lietuvos Filosofijos ir Sociologijos Institutas, pp.217-235.

Savivaldybių ir apskričių vaikų globos ir spec. ugdymo institucijų veiklos analizė ir vertinimas (mokslinio tyrimo ataskaita) 2001, Vilnius: Darbo ir socialinių tyrimų institutas.

Social Education and Social Educational Practice in the Nordic Countries 2003, Nordic Forum For Social Educators, Nordisk Forum For Socialpaedagoger.

Author's

addresses:

Prof Dr Liudmila Rupšiene

Department of Social Pedagogy

Klaipėda University.

S.Nėries 5

LT-5800, Klaipėda

Tel.: +37 046 398 637

E-mail: liuda@rupeksa.com

Prof Dr Irena Leliūgienė

Institute of Education

Kaunas Technological University

K.Donelaičio 73

LT-3000, Kaunas

Tel.: +37 037 300 133

E-mail: ei@smf.ktu.lt