Why Freeter and NEET are Misunderstood: Recognizing the New Precarious Conditions of Japanese Youth

Akio Inui, Tokyo Metropolitan University, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences

1

In developed countries, the transition from school to work has radically changed over the past two decades. It has become prolonged, complicated and individualized (Bynner et al. 1997; Walther et al. 2004). Young people used to transition directly from school to stable employment, or with a very short unemployed period. In many European countries, this situation has been changing since the eighties: overall youth unemployment has increased, and many young people experience long periods of unemployment, government training schemes and part-time or temporary jobs. In Japan, this change has taken a decade later to appear, becoming prevalent by the late nineties (Inui 2003).

The transiting process has become not only precarious for young people, but also difficult for society to precisely understand the risks and problems. Traditionally, we have been able to recognize young people’s situation by a simple category: in education, employed, in training or unemployed. However, these categories no longer accurately represent young people’s state. In Japan, most young people used to move from school directly to full-time employment through the new graduate recruitment system (Inui 1993). Therefore, in official statistics such as the School Basic Survey, ‘employed’ includes only those who are in regular employment, while those who are in part-time or temporary work are covered by the categories ‘jobless’ and ‘others’. However, with the increase in non-full-time jobs in the nineties, these categories have become less useful for describing the actual employment conditions of young people. Indeed, this is why, in the late of nineties, the Japanese Ministry of Education changed the category name from ‘jobless’ to ‘others’.

2 Advantages and Disadvantages of New Classifications

As the working situation of young people changes, new terms and categories are emerging to describe them, such as status zero and NEET (Not in Education, Employment nor Training) in the UK, and freeter and NEET in Japan. In the UK, researchers and policy makers introduced these terms to recognise the precarious condition of 16 to 18 year olds as the benefits regimes changed and the category of ‘unemployed’ disappeared from official statistics. In Japan, ‘freeter’ was a term introduced by a advertisement magazine in the late eighties, combining ‘free lance’ and ‘albeiter’ (a students’ slang that means part-time or periodical side job). The term became popular as freeters increased in the nineties. In 2000, the Japanese Ministry of Labour for the first time estimated the quantity of freeters in its Annual Report on Labour (Ministry of Labour 2000). The term NEET emerged in Japan just in the last year and has rapidly become popular.

As Furlong mentions, these categories and terms have both advantages and disadvantages (Furlong 2005). The advantage is that they better capture the precarious condition of today’s young people than the traditional dichotomy between employment and unemployment does. ‘Freeter’, especially, fits the sense of those young people, as they often refer to themselves as freeters. The terms are also useful to help policy makers focus interventions on those who need it most. In Japan, the government launched some policies for freeters in these years and a few policies for NEET last year.

However, there are also disadvantages to these terms. One that Furlong suggests is the heterogeneity of those whom the terms represent. He says that in the UK, NEET includes young people who are long-term unemployed, fleetingly unemployed, looking after children or relatives in the home, temporarily sick or long-term disabled, putting their efforts into developing artistic or musical talents, or simply taking a short break from work or education. Groups of vulnerable young people who require distinct forms of policy intervention are grouped with the privileged that may not require any assistance to move back into education or employment. Furthermore, this heterogeneity can interfere with society’s recognition of problems and misdirect the focus of policies.

3 Are Freeters and NEET Idle Youth?

Freeters in Japan have been increasing rapidly since the late nineties with the rapid fall in demand for young labour. This fall is due to the radical restructuring of the Japanese economy and employment system. Many researchers point that social impacts, and most of them account it as the social structural problem (Genda 2001; Miyamoto 2002; Inui 2002). However, the mass media and many politicians have presumed that the rise in freeters is due to young people’s attitude toward work. They presume freeters avoid regular jobs requiring hard work, preferring temporary work and more free time, with parental support. In 2003, the Japanese government launched a new policy for youth, the Wakamono Jiritu Chosen Plan (plan to encourage youth/challenge for independence), that focuses mainly on how to improve young people’s attitudes toward work.

Another government report, the White Paper on Labour Economy 2004 (WPLE2004, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare 2004), announced last September the increase of NEET in Japan. Mass media have eagerly run NEET stories since then, and many politicians refer to NEET. Most mass media and politicians presume NEET are troubled young people who have no will to work. They say that NEET depend on parents and enjoy casual life, have no desire to work because of their affluent childhood, and therefore NEET need better work ethics. Others say that NEET suffer from psychological difficulties, such as depression, that prevent them from any social activity. In any case, to be a NEET is worse than to be a freeter, because freeters have at least a little will to work, but NEET have none. The dominant belief held by the media and politicians is that NEET is a problem among socioeconomically advantaged young people who have no will to work.

While these characterizations may apply to some freeters and NEET, they are very incomplete. Some of these young people have university degrees, come from middle class family back ground, and/or are engaged in musical or other activities. Some stay at home without any social contact because of depression. But it is still not known if they are representative of most freeters and NEET. In this paper, I use official quantitative data and some qualitative data to attempt to answer this question.

4 Government’s Definition of NEET

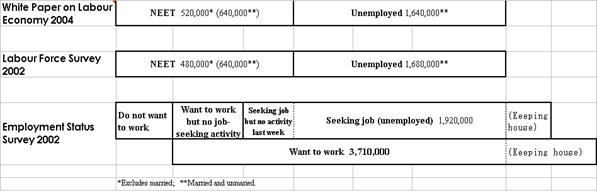

The most well-known definition of NEET in Japan comes from WPLE2004. It defines NEET as young people from 15 to 34 years old who are out of the labour force, single, not in education, and not keeping house. An important difference between this definition and the UK’s is that the UK includes those unemployed (looking for work), while Japan excludes them. This is why the mass media in Japan presume NEET have no will to work. WPLE2004 estimates the number of NEET in 2003 at about 520,000, an 8.3% increase from the previous year.

The WPLE2004’s data come from the 2003 Labour Force Survey (LFS2003). The survey asked participants about their behaviour during the previous week. If he or she worked more than one hour, the respondent is counted as ‘at work’; if he or she did not work but had any job-seeking activity, the respondent is counted as ‘unemployed’; and if he or she did not work nor had any job-seeking activity, the respondent is counted as ‘not in the labour force’. Therefore, those who are seeking jobs but happen to have no such activity in the last week are not counted as unemployed, but as NEET.

The other official data source that will be used for this analysis is the Employment Status Survey 2002 (ESS2002). ESS2002 is larger than LFS2003, but is taken only every five years. Data from the ESS2002 can only be validly compared with the LFS2002. From LFS2002, the number of NEET according to the WPLE definition was 480,000; if married people are included, the number was 640,000.

In ESS2002, there were about 3,710,000 15 to 34 year olds who were not in education, had no job and wanted to work. Among this group, 1,920,000 had some job-seeking activities. This is about 15% more than the number unemployed according to LFS2002 (about 1,680,000). The difference between ESS2002 and LFS2002 is due the survey question asked: LFS2002 asks about activities during the previous week, while ESS2002 asks about the respondent’s usual state. Another difference is that LFS2002 classifies one person to one category according to his or her main activity: employed, unemployed, in school, keeping house or other. However, ESS2002 classifies people into one of two categories: at work and not at work; those not at work are then asked if they want to work and are seeking a job. Therefore, the ‘seeking job’ category of ESS2002 includes not only those classified as unemployed by LFS2002, but also those people in LFS2002’s ‘house keeping’ and ‘other’ categories (NEET of WPLE) who are actually job seeking. This means that NEET from the WPLE2004 definition include some of those who are actually seeking jobs but are excluded from unemployed in LFS2002 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: WPLE2004 Definition of NEET and Its Breakdown

The other important point is that there are two times as many young people who want to work as those who are actually seeking jobs. Though they want to work, they have some difficulties preventing them from seeking jobs, such as no appropriate jobs around them, having a family member to look after or being tired of job seek. According to LFS, the average unemployment term for young people has been getting longer since the mid-nineties, and the longer they are unemployed, the less active their job seeking activities tend to be.

Therefore, we can conservatively estimate that more than half of the WPLE2004 NEET are willing to work or are actually job seeking. The other part includes those looking after children or relatives in the home, those temporarily sick or long-term disabled, those engaged in volunteer activities and those putting their efforts into developing artistic or musical talents. Contrary to mass media and politicians’ presumptions, idle young do not represent the majority of NEET.

5 Government’s Definition of Freeter

The features of freeters are similar to NEET. Many mass media and politicians presume that freeters prefer temporary or part-time jobs to avoid prolonged hard work, or they have not found a suitable job yet and are trying-out various jobs. Either way, they presume most of freeters prefer temporary or part-time jobs over regular ones.

There are two official definitions of freeter and estimates of their numbers. The WPLE2004 defines freeters as people 15 to 34 year olds who are not in education or keeping house and either work as temporary, part-time or dispatched workers from temporary labour agency, or are jobless and want to work as temporary, part-time or dispatched workers. By this definition, WPLE2003 estimated the number of freeters in 2003 at about 2,090,000.

The other definition is from the White Paper on National Life 2003 (WPNL2003). It defines freeters as people 15 to 34 year olds who are not in school or housewives and work as temporary, part-time or dispatched workers, or are jobless and want to work in any capacity. By this definition, WPNL2003 estimated the number of freeters in 2001 at about 4,170,000.

The main difference between these measures is that WPNL2003 includes not only those who want to work as temporary, part-time or dispatched workers, but also those who want to work in any capacity. This would seem to over-estimate the number of freeters. But it fits the condition of jobless young people: though many want a regular job, finding one is much more difficult than a freeter job. According to WPNL2003, only 14.9% of people fitting the definition of freeter wanted to be freeter at first, and 72.2% wanted a regular job. Of those unemployed, 64.3% wanted a regular job; but 51% of those who found a job got only temporary or part-time work within a year. WPNL2003 comments that those who strongly preferred regular jobs tended to be unemployed longer.

The important similarity between WPLE2003 and WPNL2003 is that both define freeter to include young people who are unemployed and NEET. Originally freeter means a young person in temporary or part-time work and not in school. Therefore, these reports’ definitions are inaccurate. However, they seems fit to the actual condition of many young people.

6 Actual Condition of Precarious Youth

I would examine other qualitative data of our research (Inui et. al. 2005). In our research we are following 90 young people who graduated from two high schools in Tokyo in March of 2003. We interviewed 51 of them 8 to 10 months after graduation and categorize twelve of them as freeters. However, most had experienced not only temporary work, but various other situations during that period. Three left regular work and, after a period of jobless, became freeters. Some started as temporary workers and then moved to other temporary jobs, sometimes with short breaks. Only one individual had worked continuously as temporary worker without breaks.

One example is Sasakura. When we interviewed her in January 2004, she was a temporary worker in a mobile phone shop. She started the job in November 2003, seven months after her graduation. She wanted to go to cooking school for cooking licence, but could not afford the tuition; so, she was saving tuition money from her temporary work. She had applied to more than ten temporary jobs since her graduation, but was rejected from all except her current one. When she questioned the working conditions during these job interviews, the employers sometimes responded with verbal abuse, which so upset her that she could not continue to seek work for a while. Until she found this job, she lived off her earnings from occasional short-term jobs (most are one day) and her mother's support; sometimes her mother was also unemployed. Examining Sasakura's experience over the 10 months, she is long-term unemployed, with two months freeter and some short periods of NEET and temporary worker.

Another example is Miyamoto. When we interviewed him in December 2003, he was working three days a week as a dispatched worker and two days a week (for one hour each day) as a yoga instructor. He started out as temporary worker in a pub, but left within a week because of bullying. After two months unemployed, he got a temporary job in a drug store, but left within a month, again because of bullying. After a few other short-term temporary jobs, he got the dispatched work in September 2003. His situation for the first half of the nine months is a mix of freeter, unemployed and NEET.

Our samples show us that:

· Many freeters work in unstable and bad conditions (often illegal)

· Their work situations are often a mix of freeter, unemployed and NEET

· Most of them have a strong will to work but find it very difficult to get a regular job or even a rather continuous temporary job

7 Social Background of Freeter and NEET

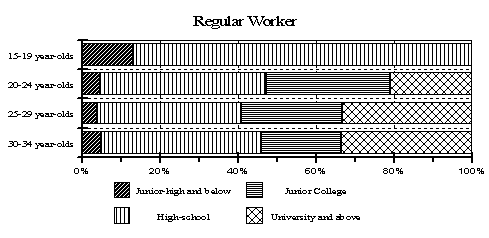

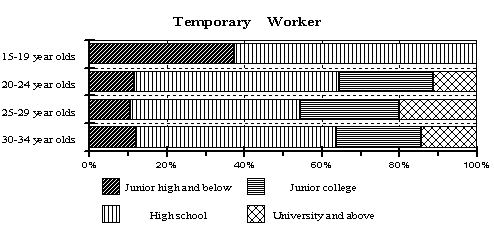

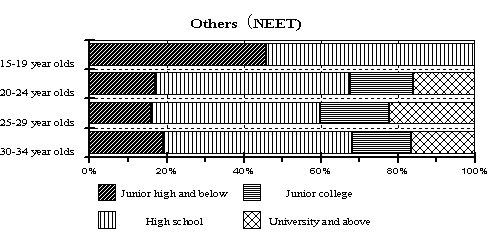

In the last section, I would examine the social background of freeter and NEET. Figure 2 shows the academic qualifications of temporary workers (freeters), and those who are jobless and not in education or keeping house (NEET)[1]. In general, NEET and freeters have lower qualifications than regular workers. Among those aged 25 to 29, the probability of being NEET is four times greater for those whose highest level of education is junior high or less, as compared to those whose highest education is junior college, specialized training college, college of technology, university or higher. And the probability of being freeter in this age group is 2.5 times greater for those with junior high education or less, as compared to those with higher education. Conversely, the probability of being a regular worker is 1.8 times greater for those with higher education, compared to those with junior high education or less.

There is little data on the family backgrounds of freeters and NEET. Based on data from the Japan Institute of Labour, Mimiduka reports that those whose fathers have higher academic attainment and higher occupational status are less likely to be freeter, a tendency that is clearer in younger age groups (Mimiduka 2002). It means that inequality is getting larger in recent years. We can generally suppose the lower family status of NEET and freeter because academic level and their family status have positive relations.

Figure 2: The Ratio of Academic Qualifications of Regular Workers, Temporary Workers (Freeter) and Others (NEET) (Data from ESS2002)

8 Conclusion

In Japan, precarious situations, such as freeter and NEET, have been rapidly increasing among young people in the last decade. Official government statistics have only recently begun to recognise theses categories. These statistics have brought public focus to this growing issue, but ambiguities in the reports have lead to misperceptions about the causes of the problem.

One aspect of the ambiguity is that the government reports focus on only a small subgroup of freeters and NEET who have no motivation to work or come from affluent backgrounds. The mass media and politicians have incorrectly taken this too represent all freeters and NEET. In reality, most are interested in working, and come from less privileged backgrounds and lower educational levels.

The other aspect of the ambiguity is that it is difficult for traditional statistical methods to recognise precarious employment situations. Young people’s employment situations can change frequently—an individual may be freeter, unemployed and NEET.

Government policies intended to help these young people do not appear to serve many of those who most require support. The policies focus on increasing young people’s will to work, but the actual problem for most freeters and NEET is a lack of stable employment opportunities and unstable status are more likely to distribute to disadvantaged young people.

To guide policy makers, we need to accurately identify the condition of young people. This requires instituting new survey categories and methods. In particular, we need to go beyond the current method of collecting only a snapshot of employment status, and also look at the employment histories of young people. Another one for Japan is to recognise disadvantaged young people’s condition deeply.

References

Bynner, J., Chisholm, L. and Furlong, A. 1997: Youth, citizenship and social change in a European context. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Cabinet Office 2003: White paper on national life 2003. Tokyo.

Furlong, A. 2005: Not a very NEET solution: Representing problematic labour market transitions among early school-leavers. Working Paper. Glasgow University.

Genda, Y. 2001: Shigoto no nakano Aimai na Huan (Ambiguous anxieties for working).: Tokyo: Chuoh-koron-sha.

Inui, A. 1993: The Competitive Structure of School and the Labour Market: Japan and Britain, in: British Journal of Sociology of Education, 3, pp. 301- 313.

Inui, A. 2002: Sengo-gata Seinenki to sono Kaitai Saihen (The post-war youth and its restructuring), in: Poritiku, 3, pp. 88-107.

Inui, A. 2003: Restructuring youth: Recent problems of Japanese youth and its contextual origin, in: Journal of Youth Studies, 2, pp. 219-233.

Inui, A. et. al. 2005: Koko Sotsugyo Ich-nenme wo Ikinuku Wakamonotachi (Young people who are surviving the first year after leaving high-school), in: Jinbun-gaku-ho, No. 359, pp. 133-148.

Mimiduka, H. 2002: Dare ga Freeter ni Narunoka (Who becomes freeter?), in: Kosugi, R. (ed.): Freeter: Jiyu no Daisho (Freeter: Costs of Freedom). Tokyo: Rodo-seisaku Kenkyu Kenshu Kiko (Japan Institute of Labor).

Ministry of Education, Science, Culture and Sports: Annual report of school basic survey. Tokyo.

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare 2004: White paper on the labour economy 2004. Tokyo.

Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications 2003: Report of employment status survey 2002. Tokyo.

Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications: Report of labour force survey. Tokyo.

Ministry of Labour (changed to Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare) 2000: Annual report on labour 2000. Tokyo.

Miyamoto, M. 2002: Wakamono ga SHakaiteki Jakusha ni Tenrakusuru (Young people are dropping down to social disadvantaged). Tokyo: Yousen-sha.

Walther, A., Blasco, A., McNeish, W. and Blasco, A 2003: Young people and contradictions of inclusion: Towards integrated transition policies in Europe. Bristol: Policy Press.

[1] The definition of freeter and NEET is a little different from that of WPLE or WPNL. In this section, freeter includes only temporary workers, and NEET includes married. Data are based on ESS2002.

Author´s

Address:

Akio Inui

Tokyo Metropolitan University

Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences

1-1, Minami-ohsawa, Hachiohji-shi,

J - Tokyo 192-0397

Tel.: ++81 426 77 2083

Email: jbb03316@nifty.ne.jp