The Deprofessionalisation Thesis, Accountability and Professional Character

Chris Clark, University of Edinburgh, School of Social and Political Studies

1

It is said that the deprofessionalisation of social work and other welfare occupations reduces workers' professional discretion and autonomy, and thus their capacity to act in the best interests of their client. Without necessarily regarding the deprofessionalisation thesis as conclusive, this paper will ask how the state's control of the role and task of social workers impacts on their role-implicated obligations as professionals. If workers are reduced (as claimed) to the status of mere functionaries in systems they neither approve of nor control, does this exonerate them from bad outcomes or service failures? How should we view the dramatic increase in formal regulation now seen in the UK – as professionalisation or deprofessionalisation? The paper will argue that whatever the drift of policy, workers remain in some measure personally accountable. Service failures imply faults of practical reason that are partly attributable to the moral and intellectual character of professionals as individuals. It is therefore up to professionals, and their organisations, to attend to the improvement of professional character.

2 The deprofessionalisation thesis

I want to start by describing what I will call the 'deprofessionalisation thesis'. It has already been outlined by the organisers of this conference. I am sure that many of us believe it represents an important critique of developments in the welfare state.

The deprofessionalisation thesis contains the following arguments:

Part 1: Policy Shifts

· Welfare policy is moving away from the key concepts and values of inclusion and citizenship

· In welfare policy the aims are:

o to control public expenditure

o to shift responsibility from the public sector to the private sector (including NGOs)

o to shift responsibility from formal services to the private individual/family

o to maintain/increase social control (e.g. in responsibilities of parents; workfare; crime and deviance)

· Because of these policy aims, the work environment of welfare professionals is changing:

o more prescription by policy and by management of aims and methods of intervention

o more regulation and control of procedures, outputs and costs

Part 2: Changes in Professional Role

· This means professionals have reduced opportunity to choose broad objectives (autonomy) and reduced discretion in how they treat individual cases

· Sometimes welfare workers have to do things that are contrary to their professional opinion of the client's best interest.

· Instead, professionals are increasingly required to enforce policies and objectives that are not of their choosing ((Jordan and Jordan, 2000): 'enforcement counsellors')

· More welfare policies are carried out by workers who are not required to be professionally trained

· The result is a process of deprofessionalisation. Workers in welfare can no longer offer clients a proper professional service because as workers, they do not have the necessary authority and resources. Instead of being professionals they become functionaries.

I need to explain my own view of this thesis. It seems to capture several important aspects of contemporary policy in a unified scheme of explanation. It certainly reflects the worries that you can hear from many social workers in the public sector. But I do have some reservations about it. The question of whether welfare professionals really have less autonomy and discretion than they did, for example, 30 years ago is an empirical question and we do not have good research to answer it. Although the social work of 30 years ago was certainly much less prescribed and regulated, it can be argued that it also had less effective tools, far fewer resources and much less legal power than social work today. It is not obvious to me that the less regulated policy environment of yesterday was more effective in promoting social inclusion and the welfare of citizens than today's highly complex systems. One could even say that today's social workers are more professional because they exercise much stronger and more varied powers on behalf of society, instead of – as before – just having small regions of professional autonomy surrounded by large areas of professional ineffectiveness. And briefly, there is no reason to think that spending on social welfare is decreasing. In the UK, spending on social work increased even in the Thatcher years.

3 Who is responsible when things go wrong?

Professionals are accountable – that is true almost by definition. Professionals not only accept, but claim, responsibility for providing a good service. If a service fails, professionals have a moral and practical responsibility for making reparations. Freidson (Freidson, 2001) refers to the idea that professionals must be held accountable for their actions as part of the 'professional project'.

This is the standard idea of professional accountability. I want to take one example of a service failure to illustrate the difficulty with this idea in practice. Sadly examples of this type will be quite familiar to you.

Caleb Ness was an infant of 11 weeks, living in Edinburgh, who was killed by his father. The father was found guilty of culpable homicide. The family was well known to the social work and health services and the police. They had serious concerns about the parents' ability to look after their baby. The mother's older children had been in public care and she was a known drug user. The father was known to have serious psychological problems.

The enquiry report came to the following conclusion:

“No single individual should be held responsible. We identified fault at almost every level in every agency involved. Many concerned professionals did their best for this family, but too many operated from within a narrow perspective without full appreciation of the wider picture. We are concerned that, two years after Caleb’s death, there is still complacency about this blinkered approach to child protection, particularly at a management level.

We are aware that many of our recommendations are not new, and that many have been made before, in earlier reports and reviews.”

(Report of the Caleb Ness Enquiry, Chair Susan O'Brien, October 2003)

This example illustrates a very general problem. Service failures in large and complex organisations are hardly ever clearly the responsibility of one person alone, or even a small clearly identifiable group of persons. It can seem that if, to some degree, everyone was responsible, then in the end no-one is really accountable. Obviously this makes the claim of professional accountability seem somewhat empty.

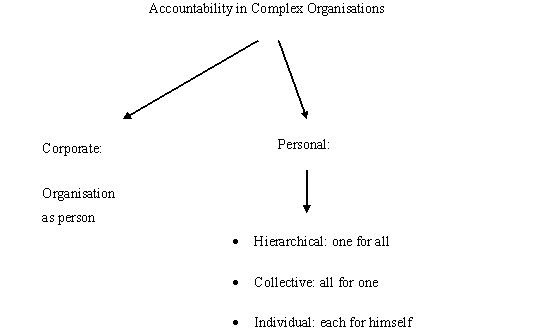

Mark Bovens (Bovens, 1998) refers to this as this problem of accountability in complex organisations as the ‘problem of many hands'. In Bovens' analysis, accountability can be seen as either belonging to the organisation as an entity in itself, or to the persons as individuals who work within it. Here is Bovens' scheme, simplified:

Figure 1: (after Bovens, M. 1998: The Quest for Responsibility: Accountability and Citizenship in Complex Organisations. Cambridge University Press).

Bovens' conclusion is broadly that all these models of accountability have their place, but none is a panacea for the problem of many hands. Of course, there are circumstances when services break down which we do not consider to be culpable failures – I mean unpredictable disasters or demands that it was never intended the organisation should be able to cope with. But under normal circumstances – when a service fails that was the acknowledged and accepted responsibility of the organisation – the responsibility of individuals for their activities as professionals cannot be completely eliminated. While I do not have space to develop this argument further, it is also the general conclusion in the literature that professionals cannot avoid all personal responsibility for the consequences of their actions.

I will base the rest of my discussion on this conclusion. Professionals are responsible for their conduct. Failure to carry out their responsibilities properly usually involves an element of culpability. The conclusion of the Caleb Ness report (and one could quote many other examples) that no single individual should be held responsible is not an argument that no-one should be held responsible.

4 Professional expertise: knowledge and character

I am saying that professionals have to accept responsibility for service failures because that is part of what it means to be a professional. How are we to understand the professional's engagement with this responsibility? What kind of relationship exists in the professional's mind between the privilege and burden of responsibility, and the way he goes about his daily work? Does being a professional mean approaching one's work responsibilities in a special way?

I think it is clear that this is just one aspect of the wider question: how do professionals think in action? How do we approach, appreciate, analyse, engage and tackle the problems that come up in everyday work? What is the nature of professional expertise?

Now this is a very big subject, so I will treat it rather schematically and perhaps over-simplify. I will say that there are two ideal-type ways of thinking about professional expertise. I will call them respectively knowledge focused and agent focused.

3.1 The knowledge focused perspective

The knowledge focused perspective concentrates on the advanced scientific and technical knowledge of the subject area:

Professional Expertise (1): Knowledge perspective

· formal scientific knowledge: systematic and theoretical

· based on accredited research by recognised authorities

· written and publicly accessible (libraries, journals); publicly disputable

· offers explanations of natural and social phenomena

· recommends explicit methods for intervention, for example:

o case management

o cognitive-behavioural methods

o risk assessment

· the validity of these interventions rests upon their being evidence based (tested by approved scientific methods)

According to this concept, professionals' expert knowledge is informed by the familiar logic of western science and its application in technology or applied social interventions. Scientific knowledge is advanced by accredited research, reported in the academic media and transmitted in the textbooks and industrial journals of the relevant scientific subject. Well known conventions of validity and reliability are very widely accepted for the secure advancement of scientific knowledge.

The logic of the scientific method applies not only in the physical sciences and their tangible technological products; it is also pressed to work in the services and industries designed to change human understanding, attitudes and behaviour – for example, advertising, teaching, political campaigning or criminal corrections. In some fields of the human services, particularly perhaps in medicine, the relevant scientific knowledge and understanding changes and develops extremely fast. Practitioners are rightly expected to have a good up-to-date command of knowledge relevant to their field.

The double assumption of scientific rationality is (i) that professional interventions should be demonstrably based on the best possible scientific understanding of the underlying problem, and (ii) should proceed by methods and protocols that have been accurately specified and objectively tested in the light of that scientific knowledge. The underlying scientific knowledge and the recommended methods of intervention will have been tested according to the most rigorous scientific standards and exposed in peer-reviewed publications to the scrutiny of the expert community.

3.2 The agent focused perspective

The agent focused perspective concentrates on the characteristics of the professional as an able and virtuous person.

Professional Expertise (2): agent perspective

· professionalism resides in the character of the professional as a person; it consists of certain kinds of personal excellence, worth or virtue (for example:

o spiritual wisdom

o ability to promote healing

o capacity to inculcate understanding

o understanding of law and justice in society

o empathic capacity for emotional support)

· a professional is someone who through a prescribed form of experience (apprenticeship, etc) has absorbed and mastered the normative methods, disciplines and practices of his/her profession

· a professional accepts personal responsibility for the intended purposes of his/her work

· a professional must be a person worthy of trust: is a fit person to be hold power and influence over non experts, vulnerable individuals, etc.

The idea of the professional as someone who holds a particular kind of standing in the community primarily because of his special worth and character as a person originates in the pre-scientific era. When medicine had little scientific basis and few effective treatments it was the expected character of the doctor that was the basis for his authority. With the rise of scientific knowledge in the hard sciences and biomedicine, the professional is transformed into the vehicle of knowledge that is beyond the reach of the lay person. And the ideal professional is one who has perfect scientific knowledge in his specialist field.

The agent focused perspective is therefore necessarily individualistic and subjective. It recognises that everyone has their own, partly idiosyncratic, ways of interpreting situations and solving problems in professional practice. It takes into account not merely the formal intellectual knowledge that the agent possesses but also that their way of doing things stems from their character, personality, values, experience, habit and so forth. Of course we know that these personal ways of acting often seem somewhat irrational, at least from the point of view of those who recommend that professional intervention be based on scientific knowledge and formal methods.

3.3 Practical reason combines knowledge and agent focused perspectives

To repeat: the knowledge focused and agent focused perspectives are ideal types. Neither one adequately describes what happens in reality. It will be obvious that an adequate model of professional expertise and practical reason requires both perspectives. Let me refer briefly to two models from the literature. The first is from Donald Schön. Schön (Schön, 1983) criticises what he calls Technical Rationality as a model of professional expertise in action, or in other words what I have called the knowledge focused perspective. Instead he emphasises the semi-articulate but fluent acquired expertise of the experienced practitioner. The practitioner is usually incapable of rigorously justifying his expertise. Problem solving in the real world is not based on fully demonstrated scientific knowledge or guided by rigorous methodologies. Instead it proceeds by what Schon calls 'reflection-in-action' that continuously adapts itself to the changing and uncertain world of practice.

My second example of a model of problem solving is from two medical educationists, Kassirer and Kopelman (Kassirer and Kopelman, 1991). On the basis of teaching and clinical experience they propose a five stage model of diagnosis: hypothesis generation; hypothesis refinement; diagnostic testing; causal reasoning; and verification. The point in this context is that they argue that diagnosis, a 'special case of unstructured problem solving' (p.7) proceeds by inductive reasoning often 'making extensive use of rules of thumb or short-cuts' (p.4) and relying on recognising familiar patterns or examples rather than knowledge of statistical prevalence. It is only partly governed by the strict logic of the hypothetico-deductive scientific method.

My conclusion on practical reason is therefore as follows. Professional expertise clearly does and should draw from scientific knowledge. But it is an error to think of professional expertise as if it consisted only of a body of rigorous scientific knowledge that is somehow downloaded into the head of the professional through training or other means. The practice of a professional's expertise consists not only the application of formal knowledge but its selection and interpretation through the character of the professional as an individual and unique person. Practical reason is always personal. To understand professional action and accountability we must use simultaneously both the knowledge focused and agent focused perspectives.

5 Service failures and practical reason

What then can we say about Caleb Ness and all the other sorry stories of service failure? I am sure the enquiry was right to 'find fault at almost every level in every agency involved'. What is quite striking in stories of organisational failure is that it is relatively rare to find outright intentions that would be regarded as morally corrupt. Even when there is clear corruption it is usually only one or a few isolated individuals in a sea of quite normal standards of morality. Much more common is ordinary stories of good intentions but ineffective practices: omissions, ignorance, overwork, poor resources, lack of training, poor organisational culture, complicated environments, and so on. Reading stories of service failure I think it is fair to describe what happens as failures of practical reason. The failures, although unacceptable, are easily understandable as ordinary human limitations.

To explain service failures as failures of practical reason is therefore to assert the importance of agent focused perspectives on professional action. How does this compare with the assumptions of the deprofessionalisation thesis? Now it is a key feature of the new managerialist policies that they purport to be based on improved scientific knowledge. They claim that their highly elaborated methods and extensive written procedures will more reliably lead to the desired policy outcomes than just leaving the choice of intervention to the whim of the individual professional. By following the books of guidelines and codes, rules and procedures, methods and treatments we will more effectively and economically reduce reoffending, or unemployment, or child abuse.

I would say that the methods associated with managerialism are biased towards the knowledge perspective. In specifying the role of welfare professionals we should, I think, reassert and reclaim the agent perspective against the one-eyed scientism of the new managerialism. We do need binocular vision here. However, in reasserting the agent perspective we are automatically committed to the significance of professional character. We should understand and welcome what is, I believe, the fact that in real life welfare professionals do not actually behave in the way prescribed by the new managerialist models. That means that professionals' capacity to be accountable for their actions rests as much on the character of each professional as an individual person as it does on the body of technical knowledge which the profession as a whole is supposed to possess and practice.

6 The test of character

Wether or not you agree with my conclusion that we must look to the character of the individual professional in order to ensure proper accountability of professional services, you may be interested to know of the new requirements for professional registration in the UK. Under new legislation, social workers and social care workers (which means people working in residential, day care and domiciliary care services) have to be officially registered (from April 2005) with a regulatory agency – in Scotland, the Scottish Social Services Council. Without registration it will not be possible to get a job. This belatedly brings social work into line with nursing, teaching and other personal service professions.

Workers who register with the Council must conform to a code of practice – reproduced in part here (Scottish Social Services Council, 2003).

|

5 |

As a social service worker you must uphold public trust and confidence in social services. |

|

|

|

|

|

In particular you must not: |

|

|

|

|

5.1 |

Abuse, neglect or harm service users, carers or colleagues; |

|

|

|

|

5.2 |

Exploit service users, carers or colleagues in any way; |

|

|

|

|

5.3 |

Abuse the trust of service users and carers or the access you have to personal information about them, or to their property, home or workplace; |

|

|

|

|

5.4 |

Form inappropriate personal relationships with services users; |

|

|

|

|

5.5 |

Discriminate unlawfully or unjustifiably against service users, carers or colleagues; |

|

|

|

|

5.6 |

Condone any unlawful or unjustifiable discrimination by service users, carers or colleagues; |

|

|

|

|

5.7 |

Put yourself or other people at unnecessary risk; or, |

|

|

|

|

5.8 |

Behave in a way, in work or outside work, which would call into question your suitability to work in social services. |

It includes the requirement: As a social service worker ... you must not ... behave in a way, in work or outside work, which would call into question your suitability to work in social services. You may ask what kind of behaviour this is meant to refer to. Interestingly, the rules and norms are not explicitly specified beyond what it says here. It will be up to the discipline panels to interpret – and there are very extensive procedural rules they must follow. It is also remarkable that behaviour outside work comes under official scrutiny. Obviously, if a professional is found guilty of a major crime against the person, everyone will agree that they should be considered unsuitable. But it is clear that this test could conceivably be interpreted in a very extensive and illiberal way. Altogether it is much more plainly a test of personal character than anything found in previous legislation or in the ethics literature of social work.

7 Conclusion: the deprofessionalisation thesis and professional character

I am saying that professionals are accountable for their actions. To understand their practical reason we should refer simultaneously to both the knowledge and agent focused perspectives. I will use these conclusions to re-appraise the deprofessionalisation thesis.

The deprofessionalisation thesis claims that current social policy trends are excessively prescriptive and ultimately repressive of the autonomy and inclusion of disadvantaged citizens. It claims that welfare professionals, by being drawn in to serve these repressive policies, are losing the possibility of practising according to their true professional values. From the perspective I have offered on practical reason, I think this puts too much of the blame on social policy and not enough of the responsibility on professionals and their organisations.

Some professionals – or at least, their academic advocates – perhaps resent the new managerialism. They feel that an alien and mechanical framework is being imposed on them, that it reduces their scope for professional judgement in the best interests of their clients. But since any plausible account of professional action must, as I have argued, give full recognition to the agent perspective, to attribute the current ills of welfare to managerialist social policy is to fail to live up to precisely those true ideals of professionalism that advocates of the deprofessionalisation thesis wish to support.

There is a complementary point raised by the new compulsory professional registration. In Britain official regulation of welfare services now lays down not only methods of service delivery and procedures of intervention, but also prescribes, as we have seen, tests of professional character. This raises what, for advocates of the deprofessionalisation thesis, seems to be a paradox: more official regulation may lead to more professionalism, not less. That is certainly the intention of both the leaders of the profession who led the move to registration and the government that supported it.

The deprofessionalisation thesis perhaps offers some insight into current social policy. However, I would not accept an implication that deprofessionalisation somehow exonerates welfare professionals from responsibility for social policies they do not approve of. Because professionalism subsists to a large extent in the professional's character, professionals are accountable even in the face of methods and programmes they do not entirely support. The real core of professionalism is taking responsibility in the real world we inhabit and for the systems and policies we actually operate – not wishing we were in some kind of welfare utopia and blaming bad outcomes on unwelcome policies beyond our control.

References

Bovens, M. 1998: The Quest for Responsibility: Accountability and citizenship in complex organisations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Freidson, E. 2001: Professionalism: The third logic. Cambridge: Polity.

Jordan, B. and Jordan, C. 2000: Social Work and the Third Way: Tough love as social policy. London: Sage.

Kassirer, J.P. and Kopelman, R.I. 1991: Learning Clinical Reasoning. Baltimore: Williams & Williams.

O'Brien, S., Hammond, H. and McKinnon, M. 2003: Report of the Caleb Ness Enquiry. Edinburgh: Edinburgh City Council. (http://download.edinburgh.gov.uk/CalebNess/Caleb_Ness_Report_October_2003.pdf)

Schön, D.A. 1983: The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. London: Temple Smith.

Scottish Social Services Council 2003: Code of Practice for Social Service Workers and Code of Practice for Employers of Social Service Workers,. Dundee: Scottish Social Services Council.

Author´s

Adress:

Dr Chris Clark

University of Edinburgh

School of Social and Political Studies

31 Buccleuch Place

Edinburgh EH8 9JT

UK

Tel: +44 131 650 3909

Email: Chris.Clark@ed.ac.uk