Civic Education in Pre-Service Training Program for Teachers and Children Welfare Professionals

Introduction

This article was designed to evaluate the effects of the Project Citizen and an innovative master’s degree program aimed at preparing educators to address the social and academic needs of children in Lithuania. We the People…Project Citizen Materials [1] are an instructional product for adolescent students, which was developed and published in 1992 by the Center for Civic Education at Calabasas, California. The Project Citizen engages students in learning experiences designed to affect positively their civic development, which involves three basic components of democracy citizenship: civic knowledge, skills, and civic dispositions. In our opinion Civic Education and Democracy Schooling tradition should not only involve free, positive, and constructive participation of citizens in civic and political associations. We should and we can, on the one hand, ensure education of values, concept of social inclusion, social partnership, social capital and context of cultural diversity, which require willingness to participate in pluralistic political structures based on principles of justice and equitable distribution of material and symbolic resources. On the other hand, we analyze the civic education within the processes of social and political change. We consider that the essential role of the social educator is to provide general welfare for children and families as well as to foster the creation of school environments that can serve as places where teachers and students can experience democracy every day. In this article we explore how themes and concepts from civic education and social work fields have been woven together in this unique program to provide the foundation for its graduates to address the numerous challenges faced by children and families in contemporary Lithuania.

We study the Project Citizen experiences, the project which is used by the teachers and students in 50 states of the United States of America and more than 30 countries in different regions of the world. In this article we use the study, conducted at Indiana University, Bloomington by Social Studies Development Center and the Indiana Center for Evaluation. We evaluate the effects of the Project Citizen on the civic development of adolescent students in Indiana, Latvia and Lithuania. This inquiry began in August 1999 with the study program and ended with the publication of monograph in November 2000 needs [2] . Study was repeated in 2001 and 2002 in MA degree studies. We integrated the Project Citizen as the method of Democracy Education and Civic Education Curriculum syllabus for baccalaureate degree students (2001) and created a new Master degree program with specialization: “Civic Education and Communication”(2002). The main idea of this article is to conceptualize what skills and competencies teachers and children welfare professionals require organizing the learning processes in such a way as to promote the development of life skills for civic, social, economic and political participation.

We will briefly trace the history of the Civic Education integration in the pre - service education of social pedagogues, leisure pedagogues and social workers needs [3] study program in Social Communication Institute, Social Pedagogy’s Department, in Vilnius Pedagogical University. Civic Education methods, study program or syllabus are not models that can be imported. It can work only if it has roots. We started to adopt the Civic Education and the Project Citizen Program in Lithuanian in-service and pre-service teacher training program, when Lithuania became a democratic country, and when we could re-establish the tradition of democratic institutions. The introduction of the Project Citizen in Lithuania in pre-service program of social pedagogues is one of the examples of the initiative necessary to build democracy education tradition in Lithuania. It began in August 1997 when the College of Democracy (NGO) in collaboration with Pedagogical University started a partnership with the Center for Civic Education in California to implement a pilot program of Project Citizen. Under the supervision of the College of Democracy, the Project Citizen Classroom materials were translated into Lithuanian, and 1,000 copies of the student book were published. The process of globalization, while representing economic and social progress in many ways, also presents numerous risks for further disparities among nations and among people. The economic instability that has occurred throughout Europe, particularly in the newly created republics of the former Soviet Union, has resulted in high rates of unemployment and the collapse of many social services upon which many people depended for health and security needs [4] . According to one analyst, “The past decade has seen growing international concern with social cohesion as the social fabric in all regions of the world has increasingly been under the strain of greater inequalities in income distribution, unemployment, marginalization, xenophobia, racial discrimination, school based violence, organized crime and armed conflicts or war.” [5] Political scientists who point to the proliferation of democratically elected governments around the world since the mid – 1970’s refer to ours as the “democratic age.” But the data presented in this end-of-the-century report make clear that ours has not only been a century of bloody struggle between people and ideologies, but that it has also been a century of struggle for national sovereignty and for the individual’s democratic sovereignty within the state. In a very real sense, the 20th century has become the “Democratic Century". We adapt Democracy and Civic Education methods to our education and culture tradition and to our political and socio-economic situation. “A more fully developed democracy exceeds this minimal standard by providing constitutional guarantees for civil liberties and rights, which, if justice prevailed, are exercised and enjoyed equally by all individuals in the polity.” [6] There certainly is such democracy in the memorable words of Abraham Lincoln, “government is both empowered and limited by the supreme law of a constitution, to which the people, by the people, for the people.” [7] The process of globalization, while representing economic and social progress in many ways also presents numerous risks for creating further disparities among nations and among people.

The Department of Social Education was established in Vilnius Pedagogical University in 2000. By examining how the role of the social educator has evolved over the time, we will see how the social educator’s work operates within the context of the overall mission of schools within a democratic society. We work on new study programs and syllabus comes in economic and political transition in Lithuania. The range of educational challenges includes attracting youth dropouts and retaining them within more engaging youth schools that provide more personalized learning, or responding to the increase in the number of children in “institution for social care”. Numerous initiatives have been undertaken in Lithuania to combat these problems. Among these there is a comprehensive national school reform program that includes as one of its priorities the “improvement of social-pedagogical conditions of learning and studies.” As part of this initiative, the Lithuanian government created the position of social pedagogue” [8] to ensure optimal social conditions for learning in educational institutions and to establish a staff of special pedagogues and social pedagogues for schools and other institutions responsible for the education and socialization of young people. The professional training of the social pedagogue is defined and based on international documents regulating children’s rights and their interests, legislation and other legal acts of the Republic of Lithuania, and principles of pedagogical ethics. Social pedagogues are trained in compliance with the Law on Education of the Republic of Lithuania, 2000 – 2004 Governmental Program (Valstybės Žinios No. 98-3081, 2000), the Law on Education of the Republic of Lithuania (Valstybės Žinios No. 23-593, 1991; No. 67-1940, 1998), the National program on Children and Juvenile Crime Prevention (Valstybės Žinios No. 21-510, 1997), the program on Creation of Social and Pedagogic Conditions for Children Education (Valstybės Žinios No. 52-1696, 1999), the implementation mechanisms of the 1999 – 2003 Program on Drug Control and Prevention, the Program on Introduction of Social Educators' Position in Training Institutions, and other legal acts and approved programs of studies. Within the current context of schools the school social worker who addresses the individual problems of children facing difficulties in socialization or who are at-risk for behavior, social, or physical problems may not adequately address other important forms of education and development, notably in the area of political socialization. Social pedagogy includes a concept of promoting the well being of the whole person. This includes an educational function. Pedagogy relates closely to the French meaning of education, which includes education in schools and the social and moral education of a person. Among the concerns about the nature of social work (or youth work) in British schools expressed by (Smith, 1988) is that “social educational practice has been dominated by a focus on the individual and small group and a lack of attention to the political nature of practice”. [9] Smith suggests that personal troubles need to be understood as public issues. Thus, social education should focus not only on prevention and remediation but also a deeper understanding of the social conditions and structures that cause children to be at-risk for a variety of social problems. Social pedagogues can work in the sphere of youth work, in residential or day care with children or adults or in fieldwork settings. Their role can include the kind of work done in the UK by occupational therapists and nursery nurses. One of the most attractive features of social pedagogy is the practical training that pedagogues can receive, for example in drama or in art, so that they are equipped with techniques for direct work with groups or individuals. An important component of this knowledge concerns educating students in democracy and their role within it. Given the speed with which the Central and Eastern Europe must democratize many of the projects emanating from the U.S. partnerships include the adaptation of the existing civic education curricula. Most prominent among those adaptations is the Center for Civic Education's Project Citizen. This curriculum typifies the trend in post-communist civic education to re-involve citizens in their political lives and future as members of a democracy. The Project Citizen prescribes a format for students to investigate a public issue and develop a reasoned policy that will address the issue. Suitable to all democracies, the Project Citizen is an example of the trend to adapt existing U.S. materials that meet the needs of individual post-communist educational contexts. Research conducted by Vontz, Metcalf, and Patrick (2000) on the Project Citizen in Latvia and Lithuania indicates that this approach is successful when indigenous educational reformers collaborate with U.S. partners in teacher education programs and schools throughout post-communist Central and Eastern Europe. [10] We create our syllabus and study programs at the same time are being integrated in EU, new fields of syllabus, like: Civic Education, Education and Democratic, Critical thinking, Positive Socialization, Leisure Pedagogy, Life Long Learning, Social Exclusion and Social Inclusion, Social Partnership, Social Justice, Social Capital and etc. Social Education is primarily related to supporting the process of socialization, or the creation of conditions for children and other persons to integrate themselves into the social culture, social thinking, values and conduct, and the acquisition of the means to successfully join the ranks of society. There is an idea that voluntary organizations have great educational potential and a long history in adult education and youth work. Alexis de Tocqueville called these traits of responsible behavior the “habits of the heart” that represent the indispensable morality of democratic citizenship. [11] Europe without these “habits of the heart” firmly implanted in the character of citizens, said Tocqueville, the best constitutions, institutions, and laws cannot bring about a sustainable democracy. [12] Europe from there it is useful to look at a couple of ideas often related to community. First, it is worth looking at the idea and theory of association (and associations' life) - especially as theorists like Tonnies have set association against community (Gesellschaft and Gemeinschaft). Second, the interest in social capital is a useful way of entering into current debates about the theory and practice of community. It is also worth looking at related theory about civic community. Third, it is worth exploring the notion of community in relation to the contemporary concern with the theory and experience of globalization . To what extent, for example, does globalization threaten community? What is the impact of the so-called 'risk society' on community? Social Partnership is a “problem solving” approach where interest groups, outside and insight of organization have common aim and work together in order to agree on the policy. The Social Partners consist of the following groupings or pillars, as they are known • Community • Voluntary • NGO• Universities Employers • Trade Unions Individuals • Farmers and others.

Whereas physical capital refers to physical objects and human capital refers to the properties of individuals, social capital refers to connections among individuals – social networks and the norms of reciprocity and trustworthiness that arise from them. In that sense social capital is closely related to what some have called “civic virtue.” The difference is that “social capital” calls attention to the fact that civic virtue is most powerful when embedded in a sense network of reciprocal social relations. A society of many virtuous but isolated individuals is not necessarily rich in social capital. [13] Social capital refers to the institutions, relationships, and norms that shape the quality and quantity of the society's social interactions. Social capital is not just the sum of the institutions, which underpin a society – it is the glue that holds them together. Social capital consists of the stock of active connections among people: the trust, mutual understanding, and shared values and behaviors that bind the members of human networks and communities and make co-operative action possible. Social capital refers to the norms and networks that enable collective action. Increasing evidence shows that social cohesion — social capital — is critical for poverty alleviation and sustainable human and economic development. This web site is the World Bank’s link with external partners, researchers, institutions, governments and others interested in understanding and applying social capital for sustainable social and economic development. [14]

Family is the main actor in socialization and social education of child’s personality. In the family a child satisfies his/her basic needs for communication: here the child's basic ideas and plans become imminent and implemented. As a child grows older, he/she leaves the family and is more and more influenced by the micro and macro social environments. Socialization (also called enculturation) is the process in which the culture of a society is transmitted to children; the modification from infancy of an individual’s behavior to conform to demands of social life. [15]

An institution that plays an important role in the socialization of the individual is school . The child’s entry into school gives him/her new opportunities, but here the child also faces a number of changes. Children enter an environment with established rules, where they receive the attention of other adults, where they encounter new evaluation criteria, and where they have the opportunity to establish themselves in new spheres. For some children this is a relatively easy process; for others, particularly those for whom the school’s norms and values differ greatly from those at home, this transition can be very challenging. As we shall see, facilitating this transition constitutes one of the important roles of the social educator. The definition of “social studies” presented by the NCSS Board of Directors says: “Social studies is the integrated study of the social sciences and humanities to promote civic competence. Within the school program, social studies provide co-ordinated, systematic study drawing upon such disciplines as anthropology, archaeology, economics, geography, history, law, philosophy, political science, psychology, religion, and sociology, as well as appropriate content from the humanities, mathematics, and the natural sciences. The primary purpose of the social studies is to help young people develop the ability to make informed and reasoned decisions for the public good as citizens of a culturally diverse, democratic society in an interdependent world.” [16] While the individual and family needs of children are addressed by the school social worker, the education for democratic participation of young people, at least in the U.S., has traditionally been the focus of civic education as a branch of the social studies.” [17] Individuals who have a deep and abiding comprehension of the prevailing principles of democracy, the big ideas that define democratic government and citizenship, are more likely than other individuals to exhibit several desirable dispositions of democratic citizenship such as a propensity to vote and otherwise participate in political and civic life, political tolerance, political interest, and concern for the common good. [18] Historically, the cultural and social diversity of the American people has required that schools undertake the responsibility for the political socialization of its citizens, so schools have included courses in civics to familiarize students with democratic values and institutions and to promote active civic participation. According to a recent statement published by the Centre for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE 2003), [19] competent and responsible citizens are…

- informed and thoughtful

- participate in their communities

- act politically

- have moral and civic virtues

The purpose for engaging in those efforts was "to develop in youth the knowledge, skills, and attitudes needed to live effectively in a world possessing limited natural resources and characterized by ethnic diversity, cultural pluralism, and increasing interdependence." More fully developed conceptualization of democracy in today's world includes electoral democracy in concert with such core concepts as representational government, Constitutionalism, human rights, citizenship, civil society, and market economy. [20] For instance, the Civitas International Exchange Program produced a book of comparative lessons for democracy through collaboration between teachers from five post-communist countries and the United States. Translations and adaptations of successful U.S. programs for civic education world-wide, such as "We the People: The Citizen and the Constitution and Project Citizen," also distinguish the Civitas International Exchange Program. [21] The idea of constitutionalism is the key to comprehending an advanced conceptualization of democracy. The first office of the social organ we call the school is to provide a simplified environment. It selects the features, which are fairly fundamental and capable of being responded to by the young. Then it establishes a progressive order, using the factors first acquired as means of gaining insight into what is more complicated. The terms such as society, community, are thus ambiguous. Both of them have an eulogistic or normative sense, and a descriptive connotation; a meaning de jure and a meaning de facto. In social philosophy, the former connotation is almost always uppermost. Society is conceived as one by its very nature… Family life may be marked by exclusiveness, suspicion, and jealousy as to those without, and yet be a model of amity and mutual aid within. Any education given by a group tends to socialize its members, but the quality and value of the socialization depends upon the habits and aims of the group. [22]. Starting with the emergence of the notion of social pedagogy – as education fo r sociality - in Germany in the 1840s, the idea migrated to North America via such forms as socialized education and social education (Scott). We will also examine the idea of social education as education through social life in Britain in the 1860s (via writers such as Hole); social education as learning about society (in both North America and in Britain by the Charity Organization Society; and its use by youth workers in the early 1900s to refer to education for social relationship. Social education is the evolution of an idea. What is social education and how has it evolved as a practice and as a theory? We explore the emergence of social pedagogy and the different strands of thinking that developed in Britain and the USA [23]. Over the course of the twentieth century a number of attempts have been made, especially in some Western European countries, to integrate the roles of social worker and civic educator. It resulted in the formation of the role of social pedagogue (or educator) ; [24] the one who assumes the role of advocate for students who might otherwise find themselves marginalized within the school setting and who actively promotes democratic practices at all levels within the school. Thus, the social educator assumes responsibility for working with individuals as well as seeking influence upon the social and academic climate in the school. In Great Britain “social education is the conscious attempt to help people to gain for themselves the knowledge, feelings, and skills necessary to meet their own and others developmental needs” (Smith 1982). As early as 1908 Scott suggested that “The individual must learn that he is to be held responsible for his acts . . . He must feel that either singly or in combination with others he is the cause of what happens” (p. 281). [25] Scott placed an emphasis on education for democratic citizenship. Crucially, he recognized the pedagogic implications and advocated a self-organized approach to group work. This portrayed the school as a social organism that could be used for developing co-operative attitudes and competencies. ‘Liberty can only be realized by conduct, and its expression is always self-direction, self - organization, and self-control’ (p. 13). [26] Within the current context of schools the school social worker who addresses the individual problems of children facing difficulties in socialization or who are at-risk for behavior, social, or physical problems may not adequately address other important forms of education and development, notably in the area of political socialization. Thus, social education should focus not only on prevention and remediation but also a deeper understanding of the social conditions and structures that cause children to be at-risk for a variety of social problems. Professionals of children welfare [27] cannot study the problem individually. When creating Social Education network, social partnership, social capital and social communication are becoming a core concept. “Social capital is a metaphor about advantage. Society can be viewed as a market in which people exchange all variety of goods and ideas in pursuit of their interest. An important component of this knowledge concerns educating students in democracy and their role within it. The National Council for the Social Studies defines social studies as “the integrated study of the social sciences and humanities to promote civic competence.” [28] According to (Patrick 2001) [29] the foundation for civic competence lies in the development of knowledge, skills, and dispositions related to core concepts. In their four-component model for civic education (knowledge, intellectual skills, participatory skills, and dispositions), they identify a set of concepts that form the basis of successful civic participation. These concepts fall into the categories of representative democracy (republicanism), constitutionalism, rights (liberalism), citizenship, civil society (free and open social system), market economy (free and open economic system), and types of public issues in a democracy such as those arising from the inevitable tensions between majority rule and minority rights or liberty and equality. We believe providing students with active experience that promote the acquisition of these concepts constitutes an education for democracy (as opposed to merely about democracy) and builds a foundation for the kind of systemic intervention advocated by the field of school social work that we have described here before. In this sense, true social education can be seen as a synthesis of social work and civic education. The Parliament of the Republic of Lithuania ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child on July 3, 1995. Since then, the laws of the Republic of Lithuania have been adjusted in accordance with the provisions of the mentioned Convention. The Parliament of the Republic of Lithuania passed the Law on Fundamentals of Protection of the Rights of the Child on 14 March 1996, transferring all the fundamental rules of CRC to the national level. According to Article 2 of this Law, the fundamental rights, freedoms and obligations of the child are based upon the Constitution of the Republic of Lithuania, the 1989 Convention on the Rights of the Child, and other norms and principles of international law. In this approach there is a considerable emphasis on “learning by doing”. Most of the problems that we face in our everyday lives can only be solved by us taking action of some kind. We need to be able to deal with officials, make decisions about money, and search for information and so on. Yet little has been done in the past in formal education to help people gain the knowledge, feelings and skills necessary to perform these tasks. Globalization of the economy, internationalization and technological progress are leading to changes in production and organization in the workplace and are placing new demands for knowledge and up-to-date competence. Competence development [30] is necessary in order to strengthen competitiveness and enhance flexibility in a changing work situation, and to provide individuals with a wider range of choices and greater opportunities to fulfil their needs and desires. The Competence Reform is based on a broad understanding of knowledge, in which theoretical and practical knowledge, creativity, initiative, the development of self-confidence and social skills all work together. There must be better interaction between the providers of education and the workplace, with a view to allowing employees to take part in competence development without taking them away from their jobs more than is necessary. The Competence Reform is based on interaction between many parties: Public authorities, organizations, private and public institutions and the workplace. The reform has a long-term perspective, and implementation will take place gradually on the basis of a framework of economic and organizational requirements. Employers, employees and the public sector must contribute towards the financing, organization, preparation, development and implementation of the Competence Reform.

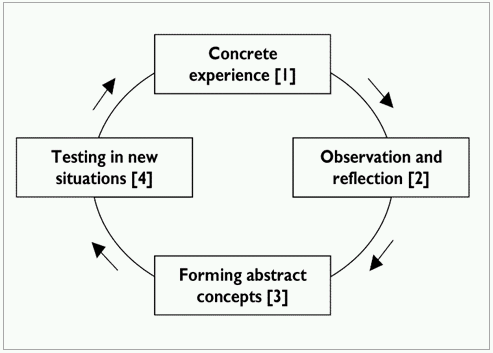

Information is necessary for spreading knowledge about the Competence Reform and creating interest, understanding and motivation in the workplace, in educational institutions and for individuals. Easy accesses to information about opportunities for education and correct guidance for adults who want to benefit from competence development are essential. We can use started in order to produce new, non-traditional methods for reaching out to the groups, which have the least enthusiasm for education. Leaders of Lifelong Learning and Learning by doing are Scandinavian Countries. The Norwegian University Network for Lifelong Learning (The Norwegian Council of Universities and State Colleges and the social partners) has developed a database for information on continuing education and training at university and college level. In Lithuanian Pedagogical University we have started the design of New Civic Education in Pre - Service Training Program for Teachers and Children Welfare professionals with taken foundations’ Lifelong Learning and Learning by doing [31] the concept an experiential learning method, which is based on three assumptions, that:

- People learn best when they are personally involved in the learning experience;

- knowledge has to be discovered by the individual if it is to have any significant meaning to them or make a difference in their behavior; and

- a person’s commitment to learning is highest when they are free to set their own learning objectives and are able to actively pursue them within a given framework.

Figure: Stages in Learning by doing (experiential) learning

In recent years there has been a growth in teaching social skills, but teachers have faced considerable difficulties because they are dealing with experience at second or third hand. In many respects youth workers have the same difficulty. The workers involved with the ice skating trip were able to use a real event with an outcome (the trip) that definitely mattered not just to the organizers but also to the other twenty or so youngsters who wanted to go skating. The fact that people were engaged in something ‘real’, rather than a classroom simulation, is a considerable aid to learning. Here the workers were able to see at first hand what was happening but for much of the time we have to deal with feelings and descriptions of events that we have little immediate or direct knowledge of. Workers are not there when her father or when his mates reject Stephen hits Debbie. Their knowledge is gained vicariously. Social educators therefore have to be skeptical about what is presented as “experience”. In a sense their most useful role is to help people identify and understand significant experiences. Yet this is not enough because one of the stranger aspects of adolescence is the way we try to cut ourselves off from certain new experiences.

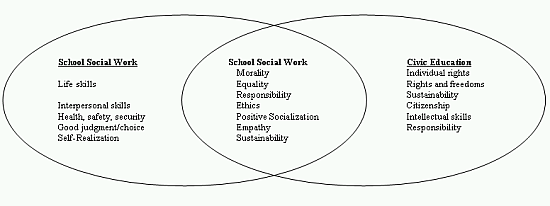

Following Figure illustrates how social education incorporates key concepts and themes from these two fields as it seeks to address the individual and social development of children within the context of a democratic society.

Figure: Social Education as a Synthesis of Civic Education and School Social Work

As school social workers shift their focus to the effects of such social ills as homelessness, domestic, gang, and school violence, and AIDS, too often scant attention is being given to the ways in which schools can promote social justice or foster active participation in democratic institutions as a form of systemic intervention on behalf of the children and families who are not adequately served by their schools. Thus, an important connection between social work and civic education has not been exploited. With the preceding as a conceptual and historical context, and before turning to a description of the Social Educator Master’s Program at VPU which does link these two fields within its curriculum, let us turn to the current situation in Lithuania and the centrality of the social educator in the transition to democracy.

The practice of social education in Lithuania is closely related to social work or youth work. The following are the key elements of social pedagogic research and practice: the interaction of institutions performing training functions in children’s socialization, the prevention of deviant child behavior, childhood security and assistance to abused and deprived children, encouragement of children’s self-awareness, social, civic and political activity, development of participatory skills, adaptability in dynamic environments, prevention of anti-social behavior, guidance in leisure time activities, and recreational pedagogy. Thus, the social educator is conceived as a professional who guides the individual development of children, actively intervenes in the child’s family and community life, and fosters the personal and political socialization of youth.

The VPU Social Educator Master’s and Baccalaureate’s Program

According to Lithuanian law, a social educator is a person holding a degree in social pedagogy (or a combined degree with a bachelor of social work and professional degree of pedagogue) who is prepared to work in social institutions performing various training functions, implementing programs in socialization, early prevention, assistance for at-risk children, social rehabilitation as well as social interactions in social groups of different levels. The key objective of the professional activity of a social educator is to support and sustain child welfare, early prevention, and training for social competence, provision of social services necessary for the child, while creating conditions for successful human socialization and civil maturity of the growing child. The purpose of the social educator is to be an advocate for the child in all-critical situations. As based on the aforementioned, it should be emphasized that the social educator must attend to the child’s problems in order to support the child or his/her custodians, be a mediator between a child and other professionals, assist in settlement of problems or suggest other professionals (institutions) likely to assist in solving such problems, if the social educator is unable to settle a particular problem himself.

Conceptual Framework. In establishing criteria for the qualities that are desirable in an effective social educator the curriculum of the Social Educator Master’s Program at VPU is organized to promote the principles outlined by Smith (1982) which include characteristics and dispositions such as honesty, consistency, flexibility, freedom of choice, equality, and confidentiality. Drawn from these values the following basic principles and duties in social pedagogic work in Lithuania have been identified and form the basis of the VPU program:

- Individual access - the dignity of every child is preserved;

- Evaluation of equal opportunities - every child is given an equal opportunity to exercise rights guaranteed by Lithuanian laws and the UN Conventions as articulated in A World Fit For Children (2002);

- Confidentiality - security of information is guaranteed including that related to problematic situations of a child, professional problems entrusted to a specialist as well as personal difficulties; the qualification and certification of social educators who violate these principles should be reviewed;

- Responsibility and competence - a pedagogue is responsible for his interventions in cases of prevention and crisis. Therefore, regular upgrading of professional qualifications is necessary.

Social educators operate in different social establishments, but they are most often employed by public agencies and are thus maintained out of taxpayers’ funds. Therefore, being responsible not only to his own institution or community but to the whole society as well, the social educator should maintain: 1) responsibility for regular improvement of professional qualifications, fulfillment of particular obligations and duties; 2) responsibility for formation of a professional team to settle social – pedagogical problems of children; 3) responsibility for initiating and guiding co-operation, supporting democratic environment and civil incentives both on an institutional and wider levels. While interacting with their clients, social educators are to base their activities on the principles of co-operation and mutual trust, support of a child and his determination, and direct intervention and support of the child’s interests. Social educator’s use Jean Piaget influential theories on intelligence development in the children in the 1920s, was also one of the first psychologists to understand that a child constructs new mental processes as he or she interacts with the environment. “What I have found in my research seems to me to speak in favor of an active methodology in teaching. Children should be able to do their own experimenting and their own research. Teachers, of course, can guide them by providing appropriate materials, but essential thing is that in order for a child to understand something he must construct himself, he must reinvent it. Every time we teach a child something, we keep him from inventing it himself. On the other hand, that which we allow him to discover by himself will remain with him visible for all the rest of his life”.

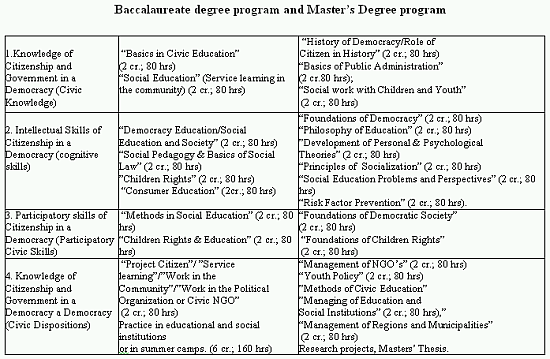

Table 1: The Integration of Civics Education into the Social Education Programs at VPU

Education is of great importance for everyone: for the personal development of individual citizens and for society as a whole. Study Programmers of Social Education in Baccalaureate and Master Degree levels integrated knowledge of Social Communication, which includes concepts on Communication, Welfare Theory, Children Rights, Right to Education as the Fundamental Human Rights, Democracy and Citizenship and Government in a Democracy, etc. Knowledge, intellectual skills, participatory skills of citizenship help ensure the students are trained general life skills aimed at preparing them for flexible and innovation work in the field. “The four – component model of education for citizenship in a democracy shown in Table 1, is congruent with the preceding descriptions of democracy and democratic citizenship illustrates how Patrick and Vontz’s (2001) [32] four components of civic education--civic knowledge, cognitive civic skills, participatory civic skills, and civic dispositions—are incorporated into the baccalaureate and masters’ programs. The first component of Table 1 pertains to knowledge of democracy, which involves teaching and learning systematically and thoroughly a set of concepts by which a democratic government in today’s world is defined, practiced, and evaluated. These concepts are: 1) representative/electoral democracy; 2) constitutional/limited government and the rule of law; 3) human right to life, liberty, equality, and property; 5) civil society or a free and open social order; and 6) market economy or a free and open economic order.

Social educators trained in the VPU Bachelor and Master Degree Program are expected to adhere to the following principles as the work within the various settings and contexts outlined above: [33]

1. Democracy and Active Participation (Positive Socialization). If a child fails to internalize the first lessons of socialization within the primary socialization institution – the family – his development will be hindered. Even under favourable conditions such as a safe environment and proper medical treatment in the case of illness, if the social functions of the family are not properly carried out or are out of balance, there will be a direct impact on the quality of the child’s socialization. Thus special attention must be paid to the socialization of the so-called at-risk children; those deprived of parental care, and homeless children. Additional positive socialization programs need to be instituted for these children that incorporate intensive socio-pedagogic assistance.

2. Equality and Justice. Children need to have equal opportunities to choose institutions of secondary education to assist in their social and creative skill development. All children need to have equal access to positive socialization experiences and extra curricular programs, to enjoy equal state support, to participate in children’s summer camps, and other socialization and creative skill development programs. We consider all children to be gifted, however, many children, starting from early childhood; do not experience optimal conditions for developing their intellectual and creative capacities. It is the responsibility of the social educator to assist in creating those conditions.

3. Human Rights and Social Responsibility / provision of better opportunities. All children need to have access to greater opportunities for participation and to take responsibility for their own lives, the life of their school, their community, their town, and their country. The child should be encouraged to actively participate in decision-making together with adults, to express opinions and to be heard. Thus, democratic education should be promoted within each and every organization that deals with children. Getting to know one’s social environment and maintaining communities to examine and learn to solve social problems are among the most effective methods applied in the contemporary educational institutions.

4. Sustainability/Diversity and inclusion. Every state should provide positive socialization programs to integrate children with disabilities, rehabilitate youth offenders, and other at-risk groups of children. Governments must ensure that more possibilities are created and maintained for those in need of social support or for socially excluded children, paying special attention to their socialization and integration.

In order to cultivate children’s social and civil capacity, social responsibility, social resistance, and self-control, social educators facilitate activities within children and youth organizations, involve them in civic activities, and promote the planning and implementation of projects (e.g. service learning, civic participation). Since the introduction of the social educator in Lithuanian schools, administrators of educational and training institutions have observed that social educators have contributed to improving the linkage between schools and other regional social agencies and report that there is now a person giving priority to social problems of children at schools. Also, the linkage with parents, children, and other child welfare institutions is improving, along with improved preventive work with children at risk, improved safety of schoolchildren and increased school attendance. Social educators have successfully applied the project method and, therefore, institutional involvement in different projects has significantly increased. Animation of cultural life in rural communities has been shown to be one of the preventive methods for successful socialization of children and youth.

Through the analysis of the new trends and challenges in Europe and the U.S. it is evident that modern schools need professionals who are able to analyze social problems in the field and who possess the skills to create concrete solutions to the problems within the social environment of children and families. These professionals must acquire the knowledge and skills to be major actors in the positive socialization process of children, performing the function of child welfare advocates. In addition, social educators, in assuming responsibility for promoting a democratic, humane, and student-centered school environment, must be familiar with the principles and practices of civic education. Since there are only 4-5 lessons per week devoted specifically to civics in Lithuanian secondary schools and teachers may select the content of these lessons from among various texts and materials (e.g., Project Citizen, Foundations for Democracy ) it is impractical for universities to provide programs that focus exclusively on civic education. Graduates would not be able to find positions in schools with only the civic education preparation. By incorporating civic education within the social education major, however, VPU graduates receive a broader preparation and have the opportunity to become more holistic and flexible professionals. This approach has been inspired by the influence of the international civic education exchanges conducted in conjunction with the Civitas program in Lithuania under the direction of Professor John Patrick and his associates at Indiana University. As a result of these contacts, VPU has integrated civic education and some other syllabus from democracy teaching fields in baccalaureate program of future Social Pedagogues (2001) and designed a new Master’s degree program with addition qualification “Civic Education and Communication”(2002).

Conclusions

The trend towards globalization and the greater unification of Europe provides new opportunities for personal growth and the social development of children. A social educator can serve as a major actor in the development of the positive socialization and the protection of children’s welfare, as well as creating an effective social-pedagogical assistance system. The family, the local community, churches, and schools together with NGOs and other informal and extra curricular organizations are the major institutions that provide positive socialization for children. The additional concentration for social educators in civic education in VPU programs is important because the positive socialization of children and welfare are directly related to the children’s welfare policy implemented by the national and local government. A lack of balance within children welfare policies in new democracies and other less well-developed countries creates a negative impact on child development and the human resources of the country. The absence of the emphasis on civic and social education in schools will limit the possibilities for some children to become full fledged, well functioning citizens. It is necessary to train professionals who are able to competently guide the socialization process within and outside educational establishments and are able to assist in the development of good citizens, educating them in civic knowledge, cognitive and participatory civic skills, and civic dispositions. The social education programs at VPU are helping Lithuania cope with the sweeping changes occurring within its borders by taking a leading role in the formation of new ideas and the creation of new institutions to benefit the society now and for the future generations.

[1] Center for Civic Education. WE THE PEOPLE. A SECONDARY LEVEL STUDENT TEXT . Calabasas, CA: Center for Civic Education, 1990. ED 339 644.

[2] Vontz, Metcalf and Patrick. PROJECT CITIZEN AND THE CIVIC DEVELOPMENT OF ADOLESCENT STUDENTS IN INDIANA, LATVIA, AND LITHUANIA .

Bloomington, IN: ERIC Clearinghouse for Social Studies/Social Science Education, 2000. ED 447 047.

[4] Diversity and Equality for Europe. Annual Report 2001, EUMC. 2002, p. 22.

[5] Tawil 2002: Responding to social exclusion through curriculum change. Geneva, p. 6.

[6] Patrick, J.J. 2003: Defining, Delivering, and Defending a Common Education for Citizenship in a Democracy / Civic Learning in Teacher Education, in: Patrick, J.J., Hamot, G.E. and Leming, R.S. (eds.): International perspectives on Education for Democracy in the Preparation of Teachers, p. 6.

[7] See Abraham Lincoln’s “Gettysburg Address”, in: Delbanco, A. (ed.) 1992: The Portable Abraham Lincoln. New York: Viking, p. 259.

[8] In this paper we consider the term social educator to be synonymous with social pedagogue.

[9] Smith, M. 1988: Developing Youth Work: Informal Education, mutual Aid, and Popular Practice. London: Open University Press, p. 93.

[10] Vontz, Metcalf, and Patrick 2000: PROJECT CITIZEN AND THE CIVIC DEVELOPMENT OF ADOLESCENT STUDENTS IN INDIANA, LATVIA, AND LITHUANIA . Bloomington, IN: ERIC Clearinghouse for Social Studies/Social Science Education, 2000. ED 447 047.

[11] Patrick: Bendrojo ugdymo formuojant piliečius demokratinėje valstybėje apibūdinimas, teikimas ir pagrindimas.//Demokratinis ugdymas socialiniame kontekste. Socialinis ugdymas. VIt. – ISSN 1392-9569, p. 13.

[12] Tocqueville 1945: Democracy in America, Volume 1. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, p.229. (Published originally in France, 1835).

[13] Putnam, R. 2001: Community-Based Social Capital and Educational Performance, in: Ravitch, D. and Viteritti, J. (eds.): Making Good Citizens: Education and Civil Society. Yale: Yale University Press.

[15] Putnam, R. 2001: Community-Based Social Capital and Educational Performance, in: Ravitch, D. and Viteritti, J. (eds.): Making Good Citizens: Education and Civil Society. Yale: Yale University Press.

[17] Jary, D. and Jary, J. 1991: Socialization, in: The Harper Colins Dictionary of Sociology. HarperPerennial, p. 452.

[18] A Vision of Powerful Teaching and Learning in the Social Studies: Building Social Understanding and Civic Efficacy. www.socialstudies.org/positions/powerful

[19] A Vision of Powerful Teaching and Learning in the Social Studies: Building Social Understanding and Civic Efficacy. www.socialstudies.org/positions/powerful

[20] ERIC Identifier: ED480420 Publication Date: 2003-10-00 Author: John J. Patrick Source: ERIC Clearinghouse for Social Studies/Social Science Education Teaching Democracy. ERIC Digest: www.ericdigests.org/2004 -2/democracy.html

[21] CIRCLE 2003: The Civic Mission of Schools. New York: The Carnegie Corporation and the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement, p. 10

[22] ERIC Identifier: ED480420 Publication Date: 2003-10-00 Author: John J. Patrick Source: ERIC Clearinghouse for Social Studies/Social Science Education Teaching Democracy. ERIC Digest: www.ericdigests.org/2004 -2/democracy.html

[23] ERIC Identifier: ED480420 Publication Date: 2003-10-00 ERIC Identifier: ED474300

Publication Date: 2003-03-00 Author: Hamot, Gregory E.. Source: ERIC Clearinghouse for Social Studies/Social Science Education Bloomington IN. Developing Curriculum for Democracy through International Partnerships.

[24] Kvieskienė, Mason, 2004: Integration Perspectives on Education for Democracy in the Preparation of Teachers. Vol 3. The Social Studies Development.

[26] Beyond Social Education//Developing Youth Work:

[27] Beyond Social Education//Developing Youth Work:

[28] In this paper we consider the term Children Welfare Professionals we gut as the synonymous with social educator, social pedagogue, social worker other professionals, who work with children welfare programmes.

[29] Building Social Understanding and Civic Efficacy: www.socialstudies.org/positions/powerful

[30] Patrick and Vontz (eds.) 2001: Components of Education for Democratic Citizenship in the Preparation of Social studies Teachers: Civic Learning in Teacher Education, Volume 1. Bloomington, In: ERIC Clearinghouse for Social Studies/Social Science Education, pp. 39-64.

[31] Patrick and Vontz (eds.) 2001: Components of Education for Democratic Citizenship in the Preparation of Social studies Teachers: Civic Learning in Teacher Education, Volume 1. Bloomington, In: ERIC Clearinghouse for Social Studies/Social Science Education, pp. 39-64.

[32] In Social Education BA and MA degree programmes we designed Portfolio of Competences, which our students created in all study years and after used it in their work places as the perfect methodical materials.

[33] Kvieskienė, G. 2004: Socialization and Children Welfare. Vilnius: Baltijos kopija, p. 35.

References

Allen-Meares, P., Washington, R.O. and Welsh, B. L. 2000: Social Work Services in Schools ( 3rd ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

A World Fit for Children (Resolution A/S-27/19/Rev.1 and Corr. 1 and 2 adopted by the General Assembly. Geneva: United Nations 2002.

Bajoriunas, Z.: Basics in Family Research. Vilnius: Vilnius Pedagogical University.

Barkauskaite, M. 2002: Teenagers. Socioeducational Dynamics. Klaipeda.

Bitinas, B. 2000: Philosophy of Education. Vilnius: Enciklopedija.

Brown, C., Harper, C., and Strivens, J. 1986: Social Education: Principles and Practice. London; New York: Falmer Press.

Center for Civic Education 1997: We the People…The Citizen and the Constitution. Calabasas, CA: Center for Civic Education.

Center for Civic Education 1998: We the People…The Citizen and the Constitution. Calabasas, CA: Center for Civic Education.

Child and Family Well-Being in Lithuania. (Country paper on the regional monitoring report), Vilnius, Lithuania: Lithuanian Department of Statistics, 2000.

CIRCLE 2003: The Civic Mission of Schools. New York: The Carnegie Corporation and the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement.

Costin, L. B. 1987: Social Work Services in Schools: Historical Perspectives and Current Directions. Washington: National Association of Social Workers.

Dewey, J. 1983: Experience and Education. New York, Macmillan.

Dewey, J.: Democracy and Education. Accessed 27/6/06 < http://www.ilt.columbia.edu/publications/dewey.html >

EUMC 2002: Diversity and Equality for Europe: Annual Report 2001. European Monitoring Centre on Racism and Xenophobia.

Gutmann, A 1987:. Democratic Education. Princeton, N. J.: Princeton University Press.

Hemming, J 1949: The Teaching of Social Studies in Secondary Schools. London: Lorigman.

Jary, D. and Jary, J. 1991: Socialization, in: The Harper Colins Dictionary of Sociology. HarperPerennial, p. 452.

Johnson, L.C 2001: The Practice of Social Work: General views. Vilnius.

Juodaityte, A. 2002: Childhood Socialization. Klaipeda.

Kvieskiene, G. 2004: Socialization and Children Welfare. Vilnius: Baltijos kopija.

Lauzikas, J. 1933: Human and Sociocultural Society. Kaunas.

Lee, R. 1980: Beyond Coping. London: Further Education Unit.

Leliugiene, I. 2002: Social Pedagogy. Kaunas.

Nie, N.H., Junn, J. and Stehlik-Barry, K. 1996: Education and Democratic Citizenship in America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

National Council for the Social Studies 1993: A vision of powerful teaching and learning in the social studies: Building social understanding and civic efficacy, in: Social Education, 57, pp. 213-223.

Patrick, J.J. and Vontz, T. 2001: Components of education for democratic citizenship in the preparation of social studies teachers, in: Patrick, J. and Leming, R. (eds.): Principles and Practices of Democracy in the Education of Social Studies Teacher. Vol. 1, Civic Learning in Teacher Education. ERIC Clearinghouse for Social Studies/Social Sciences.

Patrick, J.J. 2003: Definding, Delivering and Defending a Common Education for Citizenship in a Democracy//Civic Learning in Teacher Education. International Perspectives on Education for Democracy, in: Patrick, J.J., Hamot, G.E. and Leming, R.S. (eds.): The Preparation of Teachers. Pp. 5-23.

Patrick, J.J. 2003: Teaching Democracy. Published October 2003. Accessed 27/6/06 < www.ericdigests.org/2004-2/democracy.html >

Putnam, R. 2001: Community-Based Social Capital and Educational Performance, in: Ravitch, D. and Viteritti, J. (eds.): Making Good Citizens: Education and Civil Society. Yale: Yale University Press.

Salkauskis, S. 1936 Societal Education. Kaunas.

Smith, M. 1982: Creators Not Consumers: Rediscovering Social Education. Leicester, UK: National Association of Youth Clubs.

Smith, M. 1988: Developing Youth Work: Informal Education, mutual Aid and Popular Practice. London: Open University Press.

Scott, C. 1908: Social Education. Boston: Cinn and Co.

Tawil, S. 2001: Responding to social exclusion through curriculum change: Perspectives from Baltic and Scandinavian countries. Final Report of the Regional Seminar held in Vilnius, Lithuania, UNESCO International Bureau of Education, (December 2001): Geneva.

Uzdila, J. V. 2001: The Lithuanian Family: Critical Familistic Analysis. Vilnius.

Vaitkevicius, J. 1995: The Principles of Social Pedagogy. Vilnius: Egalda.

Vontz, T., Metcalf, K.K. and Patrick, J.J.: Project Citizen and the Development of Adolescent Students in Indiana, Latvia and Lithuania.

Zaleskiene, I. 1999: National Identity and Education for Democracy in Lithuania, in: Torney-Purta, J., Schwille, J. and Amadea, J.-A. (eds.): Civic Education across Countries: Twenty Four National Case Studies from IEA Civic Education Project Amsterdam: International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement.

Author´s Address:

Assoc Prof Dr Giedrė Kvieskienė

Vilnius Pedagogical University

Social Communication Institute

Studentų st. 39

LT-08106 Vilnius,

Lithuania

Tel: ++370 5 2752290

Fax: ++370 5 2752290

Email: giedre@vpu.lt

urn:nbn:de:0009-11-5372