A New Regime of Governing Childhood? Finland as an Example

Children’s problems have become familiar to the Finnish public since the media has portrayed many children as being ‘at risk of exclusion’ or involved in delinquent acts. The new public concern for children and childhood has been followed by interests in regulating and intervening in the lives of children and their families also in many other countries (e.g. Bloch et al 2003, Parton 2006). The simultaneous emergence of new models of welfare states and social-economic policy regime reforms present childhood (and parenting) as the current target of 'social investments' (Esping-Andersen 2002; Lister 2003). We assume the resulting improved investment, moral panic and social control are aimed at firmly linking childhood to the social economic goals of success in the markets of global capitalism, although we do not presently have a comprehensive picture of what is going on with regard to Finnish socio-legal practices. Hence we have started a research project which aims to critically analyse the inexplicable transformation in child welfare work in Finland both from an historical and a sociological viewpoint in the frame of generational and social legitimacy and solidarity. The study aims to develop a history of the present in the field of Finnish child welfare and to some extent also in comparison with some other European countries (see http://www.valt.helsinki.fi/blogs/sociolegal ).

In the following we describe some changes in the Finnish childhood policy during the past ten years. We assume that something very significant has happened in the ways of speaking of and reacting to children, as well as the young and families with children. We describe this ‘strategic’ change as a transition from a welfare policy regime towards risk politics (see Harrikari 2004). Welfare policy and risk politics can be regarded as historical formations, certain types of overall strategies containing a distinguishable set of concepts, discourses, rationalities, tactics, authorised speakers and reactions which entitles us to talk about distinctive eras or periods in governing childhood. This paper is based on some preliminary results of our research group. The group was founded in 2004; its orientation has been influenced e.g. by David Garland’s (2001), Caroline Skehill’s (2004) and Nigel Parton’s (2006) ‘history of the present’ -oriented analyses. In addition, we have adopted influences both from critical realism, and the doctrine of multilevel historical time, as we are interested in continuities and discontinuities in different contexts and levels of social interaction.

Finnish context

The status of children and families with children has changed during the past 15 years. The change took place in connection with economic, political and societal changes which were carried out in the 1990s as a result of a particularly deep and long lasting economic depression. Several Finnish studies point out that both direct implications of the economic depression and practiced social policy during the depression era were exceptionally harsh towards families with children in Finland (e.g. Bardy, Salmi & Heino 2001). Implications for policy making were manifold. For example, compared with other types of households, the incomes of families with children generally declined. Consequently, the proportion of poor and low-income families increased and the number of children below the poverty line grew. Income transfers to families with children were cut off while low-income families with children became increasingly dependent on welfare. In addition to the reductions of family allowances and the changes in working life, basic social services for families with children declined in all domains, ranging from maternity clinics to youth work.

In the following we are going to present some data why we tend to believe that during the last ten years a new type of regime in governing children, the young and families with children has emerged. Since the recession, the uncontested cornerstone of the new regime, which we call ‘risk politics’, has been ‘distributing scarcity’. Raising income transfers and increasing universal social services for families with children were the keystone tactics of the 1970s and 1980s - the period we call welfare policy. At the same time the principles of welfare policy were no more regarded conceivable, but illogical, insane and perverse.

Changes on topics and themes of child and family policy

As the first indicator of the new regime, we want to highlight the changes on the topics of public debate. We use the Finnish parliamentary initiatives as our example. In 1970s and 1980s members of the Finnish parliament produced a large number of initiatives which were aimed at supporting families by income transfers and services. The motions concerned, for example, raising family allowances, supporting young couples by low-interest loans and different types of support for maternity. The amount of initiatives of this kind increased rapidly until 1990. This era, which began from the end of the 1960s and came to a sudden end year 1991, could be called the period of welfare policy.

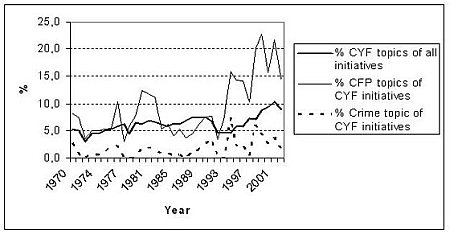

No particular topics regarding children, the young and families with children could be observed during the actual years of the economic depression. This silence indicated confusion and indecisiveness was due to changes on the borders of making politics. Definitions of welfare policy were no longer regarded possible, and no new proposals to define the new policy were made. Since the mid-1990s the parliamentary initiatives concerning children, the young and families with children increased rapidly. In 2001 nearly a tenth of all the parliamentary initiatives were targeted on children, the young and families with children (Figure 1.). The child population and families with children began to attract considerable public attention.

However, the issues of the initiatives and public debate had changed in comparison to those before the economic depression. The debate over children and the young was now permeated by concern, fear and panic (Figure 1.). For instance, crime as a societal problem has obviously been highlighted in the issues of children and the young during the past 7-8 years more than during the past decades (Figure 1.). There emerged a pronounced political interest to focus on the criminal activity of those young people who are younger than fifteen, which has been the age of criminal liability in Finland since 1894. A keystone target of public discussion has particularly been the age of criminal responsibility which it was suggested to lower several times in 1998-2004 in the Finnish parliament, and even to be removed totally. From a historical perspective, the age of criminal responsibility was never before a bone of contention in the Finnish law-making practice. It is definitely a matter of ‘post-depression period’. It is evident that this debate has been influenced by the present international discussion, especially from Great Britain (e.g. Muncie 1999; James & Jenks 1996).

The rise of early intervention and ‘hot-spot’ -thinking

Due to the changes in the national financial policy, the universal utopia of social politics became weaker and eventually faltered. The development and maintenance of the comprehensive and high-level social service system, which prevents all types of social problems among families with children, was challenged. This meant that the principle of prevention as the leading strategy was now rejected, at least in the meaning in which it was understood and implemented in the welfare policy era. New concepts were adopted and the old ones adapted. Alongside the social prevention of the welfare policy, ‘early intervention’ appeared as a dominant orientation of social policy and social work since the end of the 1990s. The concept was spreading like wildfire from maternity clinics to geriatric wards to become a leading reference point for social work.

‘Early intervention’ was an applicable concept and working orientation for the new regime where the ‘economic necessities’ and ‘the scarcity of the public recourses’ were the unquestionable bases for debate and starting points for policy-making. The expensive strategy of the welfare policy (prevention e.g. by raising income transfers and increasing social services for families with children) was considered incompatible with the main ideas of the new regime.

Despite formal similarities, there are significant material differences between the concepts of prevention and early intervention in the Finnish context. As the strategy of prevention was targeted to the whole population so that it could avoid the emergence of social problems, the strategy of early intervention does not at all aim at wide-ranging implications. Implicitly it accepts the emergence of social problems by having the intention to correct them and to fill the ‘holes’ of insufficient prevention. It does not pay attention e.g. to the issues of income distribution, inequality and poverty. Early intervention emphatically observes and allocates control activities to the problems which have already emerged. The concept reflects ‘risk-oriented hot-spot’ thinking in which control sensitivity to societal reactions is significantly lower if compared to the old idea of social prevention.

From avoiding labelling towards situational prevention, incapacitation and direct intervention

Consequently, the new regime is not much interested in the deep and complex social mechanisms which may underlie the actual problems or ‘symptoms’. It focuses on the immediately perceivable phenomena, like behaviour defined e.g. as risky, criminal, antisocial or violent. This means the concept of prevention is used in a different sense from the way it was used in the welfare policy regime. In the risk politics regime it is a question of a situational prevention perspective instead of social prevention. The perspective of situational prevention highlights the questions of controlling and ‘inhibiting’. The transformation of the concept of prevention might indicate the transformation of criminological thought in a way David Garland has encapsulated thus:

“The criminologies of the welfare state era tended to assume the perfectability of man, to see crime as a sign of an under-achieving socialization process, and to look to the state to assist those who had been deprived of the economic, social, and psychological provision necessary for proper social adjustment and law-abiding conduct. Control theories begin from a much darker vision of the human condition. They assume that individuals will be strongly attracted to self-serving, anti-social, and criminal conduct unless inhibited from doing so by robust and effective controls, and they look to the authority of the family, the community, and the state to uphold restrictions and inculcate restraint. Where the older criminology demanded more in the way of welfare and assistance, the new one insists upon tightening controls and enforcing discipline” (Garland 2001, 15).

These types of changes can also be seen as taking place in the Finnish context. On the ‘post-crime field’ and ‘individual level’, the dominant tactic of the welfare policy was to avoid labelling young offenders. Forceful reactions were believed to increase a likelihood of non-conforming behaviour in the future. In Finland this type of labelling theory thinking has not totally disappeared (Lappi-Seppälä 2006). However, new types of orientations towards ‘direct intervention’ could be perceived. For instance, the national juvenile delinquency working group (2004) noted in its report ‘immediate and powerful intervention is a generally accepted and consistent starting point in inhibiting criminal activity of the young’. This type of claim would not have been either possible nor successful as part of the welfare policy debate.

Furthermore, this ‘inhibiting’ or ‘incapacitation’ tactic is implemented not only on the individual level but also on the community and nation level. A distinctive feature of the risk politics is governing a majority of the child population by those measures which were only directed at a minority group of children in the welfare policy regime. Local child and youth curfews which have been put to practice during the past five years in some of the Finnish municipalities are a very good example of the ‘incapacitation tactics’. A study regarding youth curfews in the Southern Province of Finland (Harrikari 2006) pointed out that the curfew activity appeared approximately in 15 per cent of the municipalities (n=66). As local deviancy and tolerance factors were compared between ‘curfew’ and ‘non-curfew’ municipalities in the light of societal reaction theory (Lemert 1951), the level of total deviancy did not significantly differ between the groups. However, a level of total tolerance was significantly lower in the ‘curfew’ municipalities.

It seems that the Finnish control atmosphere has hardened on children and the young since the economic depression of 1990s. Even if the change did not happen during the actual years of depression, it could be seen, not only as a ‘post-traumatic’ societal reaction to the events of the recession era, but as a background to a new regime of governance as well. Thus, the risk politics regime uses very conservative standpoints and in the terms of Anthony Giddens (1994) ‘tradition evacuation’ as a basis for policy-making. Public concern, fear and panic are mainly based on interpretations derived from ‘basic Christian values’. ‘Parenthood is lost’ has been a widespread chant in public debate which has led - for instance - to highlight asymmetrical generational relations and the primary nature of adulthood and parenthood in relation to childhood and youth.

On the other hand, the continuous feeling of crisis has increasingly been handled with the tactics of ‘risk management’. The official solutions of ‘early and direct intervention’ could be without frills combined with a conservative ‘family movement’ in the civil society in the late 1990s (Jallinoja 2006), constituting ‘the ethos of intervening’. Children and the young are presented to be ‘risks for society’ or to be subject to different types of risks which may lead them to be societal risks later. This debate is based on ‘the escalation of evil’ (Jallinoja 2006, 109-130), in other words, the topics of improving welfare - income transfers and services, stressing children’s participation and provision - are put aside and the topics of risk politics - pornography, paedophilia, crime, mental health problems, drugs and intoxicants - are highlighted as the primary themes of the debate (cf. Parton 2006).

Consequently, at least eighty parental projects based on communitarian and Christian values (e.g. one of the projects has as a motto: ‘it takes the whole village to raise a child’) have been started all over the Finnish municipalities since the end of 1990s. In them children are emphatically seen as the objects of adult interventions. Moreover, these projects have been combined, not only with the aims of the police-led local crime prevention programs as the National Crime Prevention Program concludes 1999, but also with the local child welfare programs stressing ‘support for parenthood’ and ‘early intervention’ instead of the old ideas to promote children’s participation and provision according to the ethos of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. Together these programs and practical efforts constitute a new keystone strategy to implement the new regime of risk politics in practice.

Changes between the authorised speakers

The last indicator we will take up here is the obvious change of who are the authorised speakers concerning the problems of children and their families. The self-evident experts in these problems in the welfare policy regime were e.g. social workers, psychologists, and psychiatrists. The discourses and definitions of policy were based on the knowledge and doctrines of these professions who were also regarded as the ‘authorised speakers’, possessing ‘the truth’ of children, the young and families with children. Children and families were seen to be in need of support and therapeutic treatment.

It seems that the order of the authorised speakers has changed during the past few years. The more the status of children, the young and families has been permeated with the topics and presentations of risk politics, and when ‘crime problem’ came to be regarded as a ‘security problem’, the more the police has enhanced its share in the definitions of childhood and family policy. Focus of the interventions is no more preventing ‘symptoms’ which were believed to derive from poverty, inequality or dysfunctional family system. The focus is instead on governing and inhibiting observable behaviours to which is now reacted by the means of the police, like curfews and zero-tolerance practices (cf. Young 1999). The change is significant in comparison with the debate of the 1970s and 1980s in which the professional skills of the police were regarded as insufficient for working with children, and the means of straight control were excluded from the social sector whenever possible.

The perspectives and practices of the risk politics regime have been permeated through multiprofessional cooperation this being one of the keystone authority tactics since the economic depression. Discourses and practices adapted among these ‘battlefields for professional hegemony’ show evidence of high-level consensus over the risk politics regime. Heterogeneity of concepts and discourses has disappeared and all the cooperative professions are jointly putting risk politics into practice. Thus, the status of social work and especially child protection work has been put under critical discussion during the past few years. As the crime prevention perspective is the dominant element of the risk politics, child protection has gradually become seen as one of the essential actors among other crime prevention activities. The recent Finnish studies provide some evidence how the child protection professions have successfully been combined to carry out the crime prevention program and the strategies designed by the police (Harrikari 2006; Soine-Rajanummi & Korander 2002). This may lead to practices which contradict the norms of professional ethics and self-understanding of social workers. For instance, social work profession in the UK seem to be significantly more critical of bringing in these new influences from outside of its own doctrines and self-understanding (see Garrett 2004).

Final Comment and Conclusion

We have briefly described the recent changes of the Finnish childhood policy. We would like to state that the regimes of welfare policy and risk politics should not be seen as exclusive of each other. They have to be regarded as the sedimentary cultural layers which constantly contend for a status of hegemonic concepts, discourses, tactics, authorised speakers and practices. As mentioned above, we presume that a new type of regime - risk politics - has emerged during the past ten years in the Finnish context. A comparison and the main conclusions between welfare policy and risk politics regimes are presented in table 1.

References

Bardy, M., Salmi, M. and Heino, T. 2001: Mikä lapsiamme uhkaa (What is threathing our children?). Reports of Stakes no. 263. Helsinki: Stakes.

Bloch, M. N.,Popkewitz, T, Holmlund, K. and Moqvist, I. (eds.) 2003: Governing Children, Families and Education. New York: Palgrave.

Esping-Andersen, G. 2002: A child-centred social investment strategy, in: Esping-Andersen, G., Gallie, D, Hemerijck, A. and Myles, J. (eds.): Why we need a new welfare state. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp.26-67.

Garland, D. 2001: The Culture of Control. Crime and Social Order in Contemporary Society. Oxford: University Press.

Garrett, P. M. 2004: Talking child Protection. The Police and Social Workers ‘Working together’, in: Journal of Social Work, 4, pp. 77-97.

Giddens, A. 1994: Living in a Post-Traditional Society, in: Beck, U., Giddens, A. and Lash, S. (eds.): Reflexive Modernization. Politics, tradition and aesthetics in the modern social order. Cambridge: Polity Press, pp. 56-109.

Harrikari, T. 2004: From Welfare Policy towards Risk Politics?, in: Brembeck, H., Johansson, B. and Kampmann, J. (eds.): Beyond the Competent Child. Roskilde: Roskilde Universitetsforlag, pp. 89-105.

Harrikari, T. 2006: Lasten ja nuorten kotiintuloaikoja koskevat käytännöt Etelä-Suomen läänin alueen kunnissa (Child and Youth Curfew Activity and Regulations in the Southern Province of Finland. Publications of State Provincial Office of Southern Finland) no. 106. Helsinki: Hakapaino.

Jallinoja, R. 2006: Perheen vastaisku (The Backlash of Family). Helsinki: Gaudeamus.

James A. and Jenks, C. 1996: Public Perceptions of Criminal childhood, in: British Journal of Sociology, 47, pp. 315-331.

Lappi-Seppälä, T. 2006: Finland: A Model of Tolerance?, in: Muncie, J. and Goldson, B. (eds.): Comparative Youth Justice. Critical Issues. London: Sage, pp. 177-195.

Lister, R. 2003: Investing in the citizen-workers of the future: Transformations in citizenship and the state under New Labour, in: Social Policy & Administration, 37, pp. 427-443.

Lemert, E. M. 1951: Social Pathology. A systematic approach to the theory of sociopathic behaviour. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Muncie, J. 1999: Institutionalised intolerance. Youth justice and the 1998 Crime and Disorder Act, in: Critical Social Policy, 19, pp. 147-175.

Parton, N. 2006: Safeguarding Childhood. Early intervention and surveillance in a late modern society. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

Skehill, C. 2004: History of the Present of Child Protection and Social Work in Ireland. Lewinstone: The Mellen Press.

Soine-Rajanummi, S. and Korander, T. 2002: Sosiaali- ja nuorisotyön näkökulmia rikoksentorjuntaprojektissa. (The Perspectives of Social and Youth Work in the Crime Prevention Project), in: Korander, T. and Soine-Rajanummi, S. (eds.): Kahdeksalta Koskarille - samantien sakot (Koskari Eight o’clock - immediately fined). Studies of the Police Academy, no. 13. Helsinki: Edita, pp. 170-210

Young, J. 1999: The Exclusive Society. London: Sage.

Appendix

Table 1. Historical formations of Welfare Policy and Risk Politics

|

|

Welfare Policy |

Risk Politics |

|

Child and family policy in relation to economic policy |

Strong economic growth, increasing income transfers & services for families with children |

Scarce economic resources, conditioned by ‘new global economy’ and ‘new public management’ |

|

Status of public sector |

A call for protection from the state, society causes deviance, best of citizens |

A demand for protection by the state, deviance causes problems for society; protection of society |

|

Rationality of decision making |

Cost-effectiveness analysis, weighing advantages and disadvantages |

Risk rationality, rhetoric of the worst case, ‘the art of scaring’. Continuous feeling of crisis. |

|

Keystone positions of children, the young and parents |

Well-being child, child possessing rights. Projects promoting children’s participation and Supporting parents by income transfers and services for families with children |

Childhood as risk, children at high-risk, youth in danger of marginalisation, identifying previously ill-mannered children Discourses of parental responsibilities and ‘parenthood is lost’. Tradition evacuation. Ideologies of communitarism - parental groups and adult-leaded educational projects (it takes the whole village to raise a child) |

|

Key actors in child policy |

Social workers, psychologists, psychiatrics |

The police, multiprofessional co-operation, risk calculation professionals |

|

Feature of social problems |

Focusing and influencing deeper mechanisms behind behaviour (symptom). |

Focusing, influencing and governing visible behaviour (risk, antisocial, criminal, violent) |

|

Measures, techniques, methods |

Prevention, avoiding labelling, rehabilitation |

Early recognition and intervention, immediate and powerful intervention. immediate ‘correctional’ measures. Incapacitation.

|

Figure1. Percentages of 1) initiatives regarding children, the young and families with children (CYF) of all initiatives, 2) the topics of concern, fear and panic (CFP) of CYF initiatives, and 3) crime topic of CYF initiatives in the Finnish parliament 1970-2002 (N=118 867).

Author´s Address:

Dr Timo Harrikari / Prof Mirja Satka

University of Helsinki

Faculty of Social Sciences, Department of Social Policy

Snellmaninkatu 10 (Box 18)

FIN-00014 University of Helsinki

Finland

Tel: ++358 9 191

Fax: ++358 9 191 24564

Email: timo.harrikari@helsinki.fi / Mirja.Satka@helsinki.fi

urn:nbn:de:0009-11-7314