Imprisonment in old age: The case of Germany

Stefan Pohlmann, University of Applied Sciences Munich

Abstract: Currently, there is a lack of reliable data on the effect imprisonment can have on the delinquent’s mental state. Little is known how individuals aged over 60 psychologically and socially adapt to long-term imprisonment, as well as into the enduring effects of their transition back into society post-release. In particular, the attributions through which older prisoners navigate and endure incarceration are insufficiently theorised and underexplored within existing scholarly literature. This article takes into consideration the perspectives of those affected. To this end, an explorative study with older ex-inmates in Germany is presented. The results illustrate different assessment dimensions. Furthermore, all findings were discussed with practice experts regarding implications for age-sensitive sentencing and resocialization. The data reflects the situation in Germany and can only be transferred to other countries and penal systems to a limited extent.

Keywords: Older offenders; age-sensitive sentencing; attribution; imprisonment; resocialization

1 Introduction

Despite the still small proportion of older persons in the German penal system, two remarkable trends in crime statistics are cause for concern (Spiess, 2022, p. 44). First, the share of 60plus among so-called long-term prisoners has risen to almost 30 percent in recent years. Second, there is an astoundingly high percentage of imprisoned people aged 70 and older, in stark contrast to the past. These developments provide sufficient reason to take a closer look at how law enforcement deals with age-related crime and how imprisonment affects elderly inmates. It remains to be seen whether the coming years will bring not only an absolute but also a relative increase.

Criminological research indicates a strong dependency of criminal behaviour on the age of the offender. While the number of crimes committed by young adults is increasing, the crime rate decreases in older age groups. This general tendency described as “the age crime curve” (cf. Loeber & Farrington, 2014; Steffensmeier, Lu & Na, 2020), is also reflected in German data (Bundeskriminalamt, n.d.). The crime rate among older people has remained largely stable over recent years (Görgen & Textores, 2023). Even in light of demographic change and the associated increase in the number of elderly individuals, the percentage is on constant level. In absolute terms, however, the number has grown due to the increased number of people in this age group (cf. Gruener & Pohlmann, in press). Moreover, the offenses committed by older persons tend to be less serious (Baier & Dreißigacker, 2022).

Interestingly, prison populations reveal a different pattern. While older offenders remain underrepresented compared to younger adults, the proportion of elderly delinquents in German prisons has increased noticeably over the last two decades (Görgen, 2022). Similar trends of a pronounced ageing of prison populations can be observed in many other countries, with supporting data from Australia (Ginnivan et al., 2022), the UK (Turner et al., 2018), the U.S. (Kheirbeck & Beamer, 2022), and Japan (Suzuki & Otani, 2023). Moreover, projections predict a significant increase of the absolute number of imprisoned older people in German-speaking countries (Görgen 2022). This nominal growth cannot be explained solely by demographic change but is also driven by harsher sentencing practices (Ghanem et al., 2023).

Obviously, official statistics only capture reported and detected crimes. As a result, the scale of problems and challenges may be underestimated. Nevertheless, considering their special needs and health risks, imprisoned persons of advanced age constitute a particularly vulnerable group. A fact that could have significant implications for court sentencing, prison placement, and rehabilitation strategies for older offenders. Yet, too little attention is currently being paid to age-specific requirements in these areas. Although demographic change has long been anticipated (Pohlmann, 2002), society has not been dealing with these issues sufficiently so far. Therefore, both research and practice are now urgently required to (re)act. This is especially relevant as aging people today remain healthier and are more active than in the past (cf. Tuichievna, Abdukhamidovna & Rasulovna, 2023) and may therefore also increasingly engage in criminal behaviour (cf. Kunz & Gertz, 2015). While still far from a mass phenomenon, this development should not be ignored with regard to law enforcement and the consequences of sanctions (cf. Merkt et al., 2020).

Research shows that the biological aging process accelerates in prisoners, and that the risks of associated geriatric symptoms increase (Greene et al., 2018). There are also indications that age-typical illnesses develop significantly earlier during imprisonment than in the general population (Starostzik, 2018). Whether this is due to lifestyle factors prior to imprisonment or to the conditions of imprisonment itself cannot be clearly determined at present. In addition to health burdens, prisoners exhibit a suicide rate up to 18 times higher than that of comparison groups in freedom (Bennefeld-Kersten et al., 2015; Fazel et al., 2017, Konrad, 2002, Matsching et al., 2006). The psychosocial and health effects of imprisonment are undoubtedly relevant, especially for the elderly. Key aspects of prison life, however, remain poorly adapted to their needs. Misplacement of prisoners, insufficient therapeutic services, inadequate staff training, and persistent legal violations within prisons have further drawn critical media attention to individual correctional facilities (cf. Schlieter, 2011). Current qualification programs within the penal system are primarily aimed at preparing inmates for successful employment. Completing school qualifications, vocational training, or higher education, however, is of little relevance for older individuals. Since most programs are designed to enable or improve a professional career upon release, people of retirement age are deprived of incentives for integration. At the same time, in line with the educational principle of lifelong learning, educational opportunities tailored to older inmates could still provide meaningful incentives. In addition to the lack of cognitive engagement, opportunities for physical activity are often limited, as sports programs, occupational therapy, and leisure activities may impose age-related restrictions. Against this background, the question arises of how the specific situation of older inmates can be adequately addressed. Since assessments of the effects of imprisonment are often provided by outsiders (cf. Suhling & Greve, 2009), the central research question is: How older people cognitively cope with prison sentences after release, and which forms of punishment appear sensible from an expert perspective.

2 Methodology

2.1 Research design

The study draws on oral interviews with older people after their imprisonment to examine subjective perceptions of detention. The focus is on cognitive and affective evaluating personal experiences of imprisonment. No emphasis is placed on objective infrastructure criteria in prisons such as structural barriers not suited for elderly people, as these already represent obvious obstacles and problems. In addition, participants completed several standardized screening tests. For comparison, a younger control group was also included. Furthermore, a small number of expert interviews with professionals in social work were conducted to contextualize the findings.

Since related studies are often conducted with only few participants, the results should be interpreted with caution, the small sample sizes making the findings less generalizable and less statistically reliable. It is crucial to validate any significant correlations with further research using more robust samples. Even though these findings can provide a preliminary understanding that guides future research.

There is also the question of the extent to which the assessments of convicted individuals can be trusted at all, as a variety of biases can occur (cf. Taylor et al., 2020). In this regard, many methodological artifacts are well documented in empirical social research. Against the backdrop of imprisonment, there is concern about interference from response tendencies that may be considered as an attempt to exaggerate positive representations of oneself. Furthermore, biases they may be caused by increased attention that comes with an examination. In social psychology and methodological research, such effects have been sufficiently described (cf. Diekmann, 2009). They are based on conscious and unconscious forms of self-deception as well as deception of others and are accompanied by exaggerations, illusions, and fade-outs. Nonetheless, the issue of trustworthiness constitutes a fundamental concern in every interview setting. Therefore, attributions in this study do provide an insight into the imprisoned persons’ views and thus more valid information about subjective prison experiences than the interpretations of outsiders.

2.2 Sample

One of the fundamental questions is when individuals are considered “old”. Given the enormous heterogeneity in age groups, chronological age proves to be a problematic construct. Any age classification therefore remains to some extent arbitrary. While the threshold of 50 years is frequently used for the label “older” by researchers in the field of criminology (Merkt et al., 2020), gerontological studies commonly consider the 60-plus age group separately (cf. Wareham, 2023). The latter definition is also more appropriate in the context of resocialization measures which are strongly labour market-oriented and often ill-suited for those aged 60 and above (cf. Humblet, 2021).

Unlike the few existing studies that focus directly on offenders (Ghanem, Hostettler & Wilde, 2023), this study included only individuals who had already been released from prison. The aim was to provide a retrospective assessment that also captures the individual consequences of imprisonment. A total of 22 individuals participated, with a significantly higher proportion of men (N=20). The participant’s age ranged from 62 to 78 years. The exact length of imprisonment was not always specified by respondents; however, a minimum sentence of at least one year was a prerequisite for participation. Almost all participants served their sentence in a regular prison (N=19). Only three individuals reported having spent time in special units or separate, age-related support services during incarceration. A total of seven participants had served at least part of their sentence in an open prison. An exclusion criterion for study participation was a stay in a forensic psychiatric clinic to avoid a possible pathological bias in the statements. For eight of the interviewees the most recent prison term had ended only a few months earlier, while all others had been released for at least one year. All participants had been at least 60 years old at the time of their (most recent) prison sentence.

The significantly younger individuals who also responded to the call for participation in the study were used as a control group to place the findings into better context. The control group consisted of 16 former inmates, exclusively male, between the ages of 36 and 51. This group had also served prison sentences of at least one year. However, data usability in this group was significantly lower than in the actual target group. A large share expected to receive an allowance or other incentive for participation in the study and provided detailed responses only on this condition. In some cases, answers were also avoided on the grounds that the focus should be exclusively on the future or that the imprisonment had already taken place too long ago. Only the above-mentioned depression screening was consistently available as a comparative parameter for the control group. The analysis therefore focuses primarily on the findings of the target group of elderly former inmates and draws on usable comparisons only in a few respects.

The study was accompanied by four expert interviews with professionals from the field of offender assistance who deal with older ex-prisoners in their work. The discussions focused on the assessing the appropriateness of punishments for older individuals. These findings will be discussed separately after the descriptive findings on the viewpoints of the imprisoned persons.

2.3 Data collection process

The empirical results below are not representative, as the survey was selective due to the voluntary nature and size of the sample. Data protection measures ensured that participants’ personal information was processed anonymously. The investigations were therefore dependent on the voluntary and self-determined decision to participate. This required field access which does not address potential participants directly and immediately. It required advertising campaigns to encourage participation, which could only succeed in cooperation and coordination with prisons, state ministries of justice, and the prisoner assistance system. The survey also demanded an active role on the part of the participants, which could potentially be accompanied by unwelcome selection effects. Against this background, interviewing older individuals with prison experience is not only an extraordinarily sensitive but also a difficult field of investigation.

A wide range of differently organized institutions were involved, including those providing or coordinating specific services for former prisoners and those offering comprehensive assistance for older people. (cf. Maguire, Atkin-Plunk & Wells, 2019). Cooperation with these agencies and the former inmates themselves was indispensable for generating the empirical data presented here and for investigating the perception of imprisonment. The participants attended two appointments. A contact and information meeting paved the way for the actual interview with informed consent and a separate screening process. The survey period covered six months and followed current applicable data protection regulations. Accordingly, all personal information was fully anonymized. An independent data protection authority reviewed the investigations, which were subsequently approved by a university ethics committee. Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study. Potential retraumatization was prevented by introducing termination criteria. Close cooperation with probation services also ensured that support was available when needed.

2.4 Investigations and data analysis

Detailed guided interviews were conducted with all study participants. In addition to the socio-demographic data the semi-structured and semi-standardized interview focused on clearly defined questions in the areas of self-image and external image, internal and external resources, life goals and biography, as well as perceived autonomy and attribution of guilt. All interviews were transcribed and systematically evaluated using a multi-stage content analysis. Content analysis is used to identify the presence of specific themes within qualitative data. This research method helps quantify and examine the frequency, meaning, and interrelationships of various attributions.

In addition, emotional components were surveyed as concomitants of incarceration. Moreover, an abbreviated geriatric assessment was performed. For this purpose, the short test DIA-S was used to screen for current depressive tendencies. This instrument is specifically designed for older people, with ten items formulated for clarity. Respondents evaluate brief statements about depression by answering yes or no (Heidenblut & Zank, 2010). The test, designed as a screening tool for use in clinical practice, is based on relevant diagnostic criteria for depressive disorders. This instrument does not replace a full diagnostic evaluation but is considered a useful indicator to improve detection of depressive symptoms in clinical practice as well as in research. Investigations show good results regarding the discriminatory power of the items, the internal consistency, and the correlation with the diagnostic criterion (Heidenblut & Zank, 2014). It can also be used for younger control groups and assesses basic emotions and cognitions over the past two weeks. Following Nikolaus et al. (1994), the areas of current contacts and activities as well as housing and economic situation were queried. A separately published article illustrates the qualitative findings obtained based on selected word contributions (Pohlmann 2023a). In contrast, the following analyses focus exclusively on aggregated data and descriptive evaluations. Patterns that have been identified should be abstracted and placed in relation to one another. The findings from the reports of the older released prisoners were presented to the experts chosen for the supplementary interviews. Based on their professional experience, the results were categorized and discussed in terms of possible hardships for older inmates and measures to facilitate their return to the community upon release. In the following considerations all interviews with imprisoned persons were converted into quantitative values, enabling comparisons and highlighting underlying trends.

3 Findings

The willingness of the older participants to provide information was surprisingly high given the sensitive nature of the topic. The interviews took an average of two hours and were consistently longer and more intensive than those conducted with the comparison group.

3.1 Subjective assessments

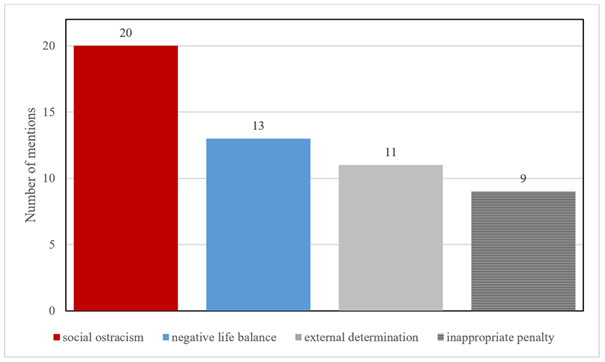

As expected from information on typical prison contexts, all respondents reported unpleasant experiences in detention. For all of them, the sanctions had a deterrent and aversive character. If one groups the statements into overarching categories, four particularly salient clusters stand out for the older interviewees, characterizing the subjectively perceived hardships of detention (cf. Fig. 1). There are striking indications of stress resulting from perceived social ostracism (N=20). It appears in the form of double exclusion, arising from the combination of old age and delinquency. According to the available statements, it is precisely this combination that results in discrimination during and after imprisonment and contributes to a negative self-image (cf. Pohlmann, 2016).

Fig. 1: Subjective detention hardships from the perspective of older participants

The older respondents were further affected by a negative life balance (N=13). Their prison sentence late in life has left them with too few opportunities to turn their lives in a positive direction upon release. At the same time, the offenders had to confront the negative life decisions that led to their detention. The restriction of autonomy that inevitably accompanies imprisonment was also perceived as a particularly sensitive and draconian sanction (N=11). This was particularly true for those who viewed their sentence as unduly harsh (N=9). From the perspective of these individuals, it was primarily a chain of unfortunate circumstances or third-party fault that led to the imprisonment. The younger comparison group also reported unpleasant experiences in detention. However, these remained vague and could not be adequately grouped together.

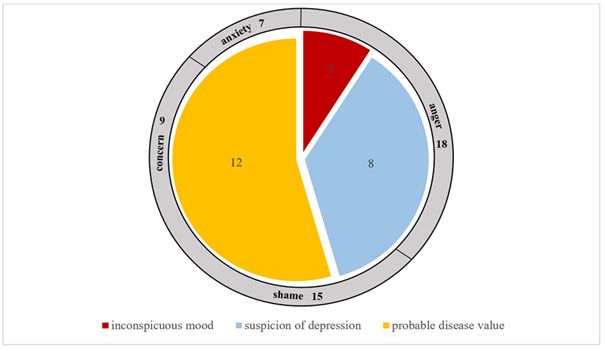

The emotions reported by the older participants during imprisonment were conspicuously negative (see Fig. 2). Anger, shame, worry, and fear, in that order, were the most frequent emotional side effects of imprisonment. The despair of many participants was repeatedly evident non-verbally during the interviews and was expressed, for example, through crying, pauses, and a breaking voice. The results of the DIA-S short test clearly demonstrate the vulnerability of the group studied (see Fig. 2). Three trends were derived from the results. A low score indicates an unremarkable mood. A higher score indicates a suspicion of depression. A threshold value indicates a probable illness. Yet, a high psychosocial need for action was evident. For twelve individuals, the results indicate a pathological tendency associated with depressed mood, excessive demands, brooding, loss of interest, dissatisfaction and inhibition of drive and thinking. For eight others, depression was suspected. Seven participants even openly reported having suicidal thoughts during or after their imprisonment. Only two participants appeared to be in an inconspicuous mood state. This alarming evidence corresponds with other studies indicating an increased risk of suicide in prison (Opitz-Welke et al. 2019; Falkingham et al., 2020). In contrast, no clear deviation was found in the comparison group of younger former inmates. Only one younger individual showed a significant illness score, and another an initial suspicion of depression. This significant discrepancy between the age groups is remarkable. Depressive disorders are considered one of the most common mental illnesses. According to the Federal Report of the Federal Government of Germany (RKI, 2022), the prevalence among the population aged 15 and older was 7.6 percent in 2021. The trends identified here suggest a significantly increased risk of illness for the group of elderly former inmates. In addition, other studies suggest that attributions and evaluations of one's own life situation tend to be significantly more positive among older people than in the group studied here (Pohlmann, 2023b). This was true even when objective circumstances appeared unfavourable. This phenomenon has been well studied and documented as the so-called “well-being-paradox” (Herschbach, 2002).

Due to the high prevalence of multimorbidity in old age, especially with respect to internal diseases, physical symptoms such as insomnia, appetite disorders or pain conditions, which can also be indications of an affective disorder were not recorded. According to these results, well-being appeared to be an exceptional condition among the participants. In response to the general question of whether the interviewees rated themselves as more physically impaired (N=13), the same (N=6), or physically healthier (N=3) compared to their peers, the answers indicate a relatively high degree of subjective impairment.

Fig. 2: Main emotions during incarceration and results on depression screening of older respondents

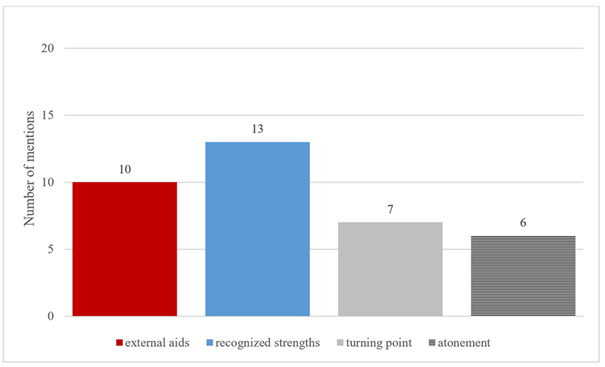

Despite these strong indications of stress, the older participants’ statements also contain distinct reflections. Here, different subjective gains or personal developments during imprisonment were emphasized. As a study by Avieli (2021) has already shown, older prisoners also experience prison as a place where they receive respect and affirmation, and that offers a certain security against poverty and loneliness. Our study results point in a similar direction (cf. fig.3). The interviewees reported being able to recognize and make use of their own strengths in detention (N=13). In this context, the respondents mentioned their own adaptability, life experience, the ability to lower their expectations and the support they received from outside. In addition, the participants noted external support (N=10), which can be interpreted as the prison taking over responsibilities. These include the transfer of planning, clear and manageable rules for everyday life and simplification of one’s own way of life compared to life in freedom. This is supplemented by statements that indicate prison time was regarded as a turning point in life (N=7) going hand in hand with purification and a conscious decision to steer future life in a new direction. Another group of respondents accepted imprisonment as a just punishment and legitimate form of atonement for their wrongdoings (N=6).

Fig. 3: Positive aspects of detention from the perspective of older respondents

These results show that there were different subjective assessments among older respondents. Nevertheless, it is interesting to note that the people surveyed here do not exclusively name positive or negative aspects but were able to differentiate between the individual aspects. The majority concluded that positive features of imprisonment exist alongside negative aspects (N=17). However, the areas mentioned were not equal and showed different levels of significance. The statements made it clear that the aspects of detention that were classified as stressful clearly outweigh the positives.

The control group of younger respondents also reported positive aspects associated with imprisonment. As in the case of stress reports, however, these statements do not allow for clear categorization and remain ambiguous.

The survey of the current social situation revealed a complex picture for the older respondents. Regarding contacts and social support as well as housing and economic situation, the majority of responses showed dissatisfaction (see Fig. 4). Only in the case of social activities were the responses more balanced, indicating a higher level of satisfaction or a neutral assessment (both N=8).

Fig. 4: Recording the current social situation of the older respondents

Even if there was only a low statistical effect size due to the small number of participants, it was important to examine possible interactions in the data to uncover initial patterns or relationships that may merit further exploration. The results showed a correlation pattern between the values recorded for the perception of detention on the one hand and the social situation and the depressive tendency of the elderly on the other. A negative experience of detention described in Fig. 1 correlated with a significantly higher risk of depression (r=0.77). At the same time, older respondents with a higher level of satisfaction regarding their current social situation were also more likely to report positively about their past imprisonment as illustrated in Fig. 3 (r=0.80). Considering the very high depression risks, however, even those with positive experiences of imprisonment were not protected from a pathological manifestation. Here, a “ceiling effect” came into play. Accordingly, positive prison characteristics did not protect from psychological stress risks or manifest disorders, at least for the group studied here.

3.2 Exemplary experiences of professionals in the field of offender assistance

The empirical results presented are based on a selective survey due to the voluntary nature and size of the sample and are hence not representative. To increase the study informative value of the study results, a supplementary qualitative survey was also conducted. Qualitative interviews conducted with a small number of professionals from the field of offender assistance helped to put the survey results from the group of ex-offenders into context. The experts interviewed confirmed that their older clients generally had a very high need for help, which was in line with results from previous studies (cf. Farrall, 2022). According to the professionals interviewed, maintaining social contacts and a familiar living space or the prospect of an adequate living arrangement (assisted living, placement in a retirement home) were of central importance for ex-offenders. From the practitioners’ perspective, these aspects were essential prerequisites for reintegrating older inmates into society (cf. Bruggencate, Luijkx & Sturm, 2018). In addition, financial security after imprisonment, e. g. in the form of basic security, was central. A decisive factor for a good prognosis is the so-called social reception area, such as the former inmates’ family, friends, or an institution supporting the person concerned. According to the experts, successful transition management after imprisonment was possible provided that financial provision and social integration were in place and housing could be obtained. In addition, social involvement, especially in leisure activities, was central for this age group.

The focus of reintegration assistance has so far been on finding suitable places in nursing or retirement homes for released offenders (cf. Oswald, 2022). Undoubtedly, our study’s participants were better resourced than those participating in classical release planning and transition management from prison, which typically focuses on particularly vulnerable and in need of care ex-offenders (cf. Pruin, 2017). In principle, the situation was especially difficult for people discharged without relevant social contacts outside prison, as there are hardly any adequate residential facilities for this clientele. This situation was further complicated by the fact that from the age of 65 the cost of housing is no longer covered by the supra-local social welfare agency but falls into the responsibility of the municipality in which the person had their last place of residence. Municipal facilities operating in accordance with § 67 of the German Social Code XII were often not barrier-free. Finding adequate forms of housing for older ex-prisoners with health restrictions who require care was associated with considerable difficulties. Especially for the very old, assisted living facilities or alternatives on the open housing market were scarce. Placements in retirement homes often became difficult as ex-prisoners often lacked an official classification of the care needed from social security institutions.

Even for those with an officially recognized care level, a placement in a nursing home was associated with obstacles, as criminal convictions were often considered an exclusion criterion. In addition, health insurance is often a critical issue for lifelong inmates who retire while imprisoned. According to the experience of professionals from the probation service, people aged 70 and older without social or financial resources have a particularly small chance for a positive life trajectory or successful ageing after prison. Without claiming to be exhaustive, the results presented here are therefore not random findings. They provide exemplary indications of the effects of imprisonment in old age. While we cannot claim the data to be representative, this excerpt already illustrates the broad spectrum of perception and experience. Practice experts involved agree that alternative penalties for older offenders are not being adequately examined and that unnecessary hardship for this group is being caused by the traditional custodial system. How such alternatives could be designed will be discussed in the next chapters. In the experts’ view, current experiences of age-adapted penal institutions (cf. Stöver & Weyl, 2023) should be used primarily for long-term prisoners.

4 Discussion

Currently, there is a lack of empirical surveys of suspected, convicted, and imprisoned individuals of older age (cf. Crewe, Goldsmith & Halsey, 2022). The systematic investigation of elderly criminals breaks a taboo. Crimes and punishment in old age do not fit common stereotypes (Pohlmann, 2022). In the public perception, this area of research is at best a marginal topic. This neglects how dealing with elderly prisoners could initiate new perspectives in criminal prosecution and sanctioning. Despite the lack of transferability and verifiability of the data, an explorative procedure (cf. Seddig & Reinecke, 2017) or exemplary presentations of individual cases (cf. Sudholt, 2022) remain essential.

The findings presented illustrated that older people assess their own imprisonment as a massive life changing event with serious long-term effects, in particular high levels of pathological stress (cf. Crawly & Sparks, in press). Above all, social image, personal failure, the forced loss of self-determination and a negative life balance in connection with a lack of options for changing one’s life play important roles. In addition to the consequences of imprisonment, which are perceived as massive hardships and emotional burdens, positive aspects can also be identified in the assessments. These include support services and assistance during and after release from prison as well as the perception of one’s own and others’ coping resources. Despite the lack of representativeness and the limitations of the study, the results point to a hitherto underestimated breadth of perceptions within the group of people affected (cf. HMIPS, 2017).

Undoubtedly, the sample studied here was a selected group of older ex-prisoners with residual resources, not generally representative of older people after imprisonment. However, the data still clearly showed a substantial age risk of mental illness. The long-term strain on mental health associated with imprisonment should be factored into the sentencing considerations, especially for older offenders. It is astonishing how little was known about the subjective dimension given by imprisoned persons in the assessment of appropriate prison sentences.

It is noteworthy that the survey revealed not only interindividual, but also intraindividual differences in subjective perception. This means that the study participants differentiated between various aspects of detention. Most participants mentioned both drastic impairments caused by imprisonment and supportive experiences such as different types of help from family, fellow inmates, or prison staff. Yet the statements received from those affected indicate variances in the experience of imprisonment and should therefore also be assessed separately. The attempt to divide the data into different assessment categories should be seen as an initial collection of relevant factors. Regardless of whether the ex post facto explanations given prove ultimately valid, the findings show very clearly that there cannot be only one view on imprisonment. It also becomes evident that the basic conditions for imprisonment, as well as the duration and implementation of the sentence, need to be carefully weighed against possible punishment alternatives for older people. Ultimately, this is the yardstick by which a modern and humane penal system in an aging society must be measured.

The fundamental question is actually achieved by imprisoning old people in an aging society. Section 2 of the German Prison Act states that the main goals of imprisonment are not only to protect the public and prevent recidivism, but also to enable offenders to lead a life of social responsibility in the future. Even if legal commentaries equate the formula “life in social responsibility” with a life without criminal offenses, such an operationalization seems rather short-sighted. Rehabilitation can also be interpreted in terms of social participation and acceptance of responsibility.

Imprisonment is not only about atoning for crimes and exacting retribution. A humane and modern legal system should always consider alternatives to locking away offenders. This requires persuasion – after all, broad public opinion tends to focus on retribution and protection against perceived danger (Ramsbrock, 2020). Addressing the public’s fear of crime and need for punishment is not necessarily tied to imposing prison sentences. Rather, an open-ended examination is needed to determine which measures deter, help restore order and prevent recidivism.

The consideration of a life course perspective remains an important factor in crime research (Farrington, Kazemian & Piquero, 2019). Perhaps it is through studying the effects of imprisonment on the mental state of older offenders that we can gain an approach to the penal system and rehabilitation programs which contributes to both effective and appropriate sanctioning of crime in an aging society. Alternative forms of punishment, such as community service, residence monitoring, reparation, or rehabilitation programs, have been suggested as potential alternatives to imprisonment. Ultimately, the decision on the best form of punishment should consider factors such as the severity of the crime, the potential for rehabilitation, and the goal of achieving justice and societal well-being. Exploratory studies such as those described here can make an important contribution to this end. While they show the negative consequences of imprisonment on the cognitive disposition of older offenders, the study also highlights positive assessments that provide insights into supportive factors to build upon. This is an important factor that has been neglected too much so far. The present study and other contributions in this special issue show that greater involvement of those affected can provide new impetus for research and practice.

When it comes to the effectiveness of different forms of punishment, there are various factors to consider (Baidawi, 2019). While imprisonment is commonly used as a means of punishment, it is important to evaluate its overall impact on individuals and society. The general assessments of the effectiveness of penal systems are not very flattering (Global Prison Trends, 2022). The tenor in Germany is also clear: too many people are still locked up without consideration for potentially better suited alternatives (cf. Schäfer & Kupka, 2021). In fact, several measures can be applied, but their effect on the group of elderly offenders has not yet been systematically tested (Pohlmann, in press). The findings above show how serious the effects of imprisonment can be in old age, even after a person has served their sentence. It has also become clear that for many older people, punishment does not end with release from prison. The statements made by offenders do not allow any direct conclusions to be drawn about the design of alternative sentences. However, the opinions of the practical experts indicate that other forms of punishment should be examined more closely. Such supplementary sentencing measures have been under discussion for some time in Germany (cf. Maelicke & Wein, 2020).

5 Conclusions

The findings show how profoundly and unsparingly a prison sentence is experienced, especially in old age. At the same time, the results emphasize the importance of support services for this group. When imprisonment is unavoidable even for older individuals, an important task remains to offer an appropriate perspective for a subsequent life in freedom. Some legislation limits options for socially responsible living upon release. For example, according to the German Criminal Code (Section 45, 1), a prison sentence of at least one year imposed for a crime is linked to a ban on holding elective public office for a period of five years. This is an aggravated condition for individuals who do not have much time left in their lives. There are many other civic roles that are conditional on a clean police record. This does not prevent delinquents from taking up volunteer work in principle, but it does make it more difficult. Sanctioning older people should not take away the compass for a successful lifestyle (WHO, 2002). It is precisely the option of contributing to society that can be meaningful and be perceived as a genuine form of probation. In the expert discussion on civic engagement, the basic psychological need to experience social belonging through one’s own actions and to gain meaning for one’s own existence emerged repeatedly (Fischer & Levenig, 2021). This should also have an impact on the orientation of offender assistance.

For people who are supposed to find their way back into “normal life” after a prison sentence, their own strengths are often not sufficient to fulfil the respective requirements. In this case, help is needed from outside. The importance of having a purpose in life has been described many times in gerontology (Hammerschmidt, Pohlmann & Sagebiel, 2014). The conventional focus on reintegration into the labour market fails for this group. Thus, alternative approaches are needed for older ex-offenders. The work of offender assistance, together with careful release preparation by the penal institution, therefore, has a supporting role. After serving a prison sentence, older people are also entitled to what Sen (2000, p. 29) described as “opportunities for realization”. This does not only refer to individual efforts, but also to the framework conditions necessary for living life according to one’s own wishes and personal values. In rehabilitation, therefore, the question must be addressed as to when and why options for action are unjustifiably restricted – especially in the case of elderly individuals. In addition to avoiding a repetition of punishment, the assessment of the effects of imprisonment must also consider which options people retain after their imprisonment to subsequently act in a prosocial manner. According to a ruling by the Federal Constitutional Court on April 27th in 2006, age does not in principle protect against imprisonment, nor does the shortness of the remaining life prohibit a maximum sentence (Case 4 StR 572/05). After assessing the underlying offense, however, the option remains to further examine a person’s susceptibility to imprisonment. This can also be understood in a preventive sense, meaning that the possibility for a socially responsible life should remain after serving a sentence. Taking this in consideration is not only the responsibility of the judges involved in sentencing (Steffensmeier, Kramer & Ulmer, 1995) but can also be part of the package of measures in the penal system and in the transition to freedom.

The descriptions of the study participants presented above indicate (see Figure 3) that a prison sentence can also create conducive conditions for this. However, work on this subject still remains too unsystematic (Farrall, 2022). It will therefore be increasingly important in the future to support elderly offenders in building and strengthening resources for a socially responsible life. To this end, they could be encouraged to engage in voluntary tasks that provide public benefit and reparation opportunities before age-related care needs and dependency become predominant.

6 Recommendations

In case that neither a risk of escape nor an imminent danger is to be expected, and the individuals concerned appear to be advisable, other security measures instead of a prison sentence can be implemented. Many countries have their own regulations and guidelines for this. If there is no alternative to a prison sentence, detention could be carried out under relaxed security conditions. Surveillance measures could be kept to a minimum. Such concepts can prepare people for a life in freedom and encourage a more responsible lifestyle. For older individuals they would also mitigate unnecessary hardship. In principle, consideration must be given to whether imprisonment makes sense at all. While the age of delinquents is not a carte blanche and should not protect them from all punishment, it could be sensible to grant deferred sentences (also known as probation), especially for first-time offenders. Provided the offense is less serious and the prognosis is positive, courts can link a conviction to certain conditions to replace a prison sentence. In this case, an imminent prison sentence can only be avoided if fixed and verifiable conditions are met. In addition, residual prison sentences could be suspended, provided that the person in prison makes efforts to atone for the harm and demonstrates through character and circumstances that a repeat offense is unlikely (Bindler & Hjalmarsson, 2017). However, a probation system tailored to the circumstances of older people does not yet exist (cf. Wahidin, 2006). There is a lack of verifiable criteria in sentencing practice that address age-related sensibilities. In addition, probation conditions often seem to focus primarily on preventing further antisocial behaviour. Far conditions seem to aim at encouraging positive behaviour (cf. Cadet, 2021).

Finally, restrictions on freedoms are also possible without detention. Electronic residence monitoring uses a digital ankle bracelet to restrict offenders to their homes or certain areas and to control which activities are available to the wearer of the device. Further options are bans on contact, revocation of a driver’s license, or house arrest. If such measures prevent a person from committing further serious crimes and detention itself entails too high risks and costs, they are alternatives worth considering. Instead of imprisonment, other types of reparation can also be considered. In addition to financial penalties, these include community service or agreements for special offender-victim compensation, which also strengthen the role of injured parties. Processes of this kind require accompaniment by professional social workers.

If imprisonment is unavoidable for older people because the violation of the law is too serious or the person continues to pose a danger, the question arises as to how an age-appropriate prison system should be designed (cf. Adrian et al., 2013). In Germany, various models are currently under experimentation. These include mixed-age and senior-specific units as well as prisons geared towards the growing number of prisoners with chronic illnesses and/or in need of care. Advantages and disadvantages of such specific prison services still need to be evaluated (cf. Kenkmann et al. 2020; Marti, 2020). It is gratifying that the special needs of older prisoners are increasingly being considered in applied research (e.g., Clinks & Recoop, 2021). Nevertheless, successful resocialization in old age still receives little attention.

Older people do not have a special or privileged legal status. Furthermore, there should be no automatic age limit for punishing older offenders. The data and conclusions presented here make it clear that the discretionary powers of the courts should systematically include considerations of age. In addition to fundamental examinations of culpability and fitness for imprisonment, greater consideration should be given to age-related differences in the consequences of imprisonment. It would also be beneficial to assign greater weight to the positive effects of imprisonment as indicated by the subjects. To obtain a complete and reliable picture of the long-term consequences of imprisonment in old age, further studies and additional methods are undoubtedly needed.

References:

Adrian, J.; Burns, A., Turnbull, P. & Shaw, J. J. (2013). Social and custodial needs of older adults in prison. Age and Ageing, 42(5), 589–593.

Avieli, H. (2021). A sense of purpose: older prisoners experiences of successful ageing behind bars. European Journal of Criminology, 1–18.

Baidawi, S. (2019). Older prisoners: a challenge for correctional services. In Ugwidike, P., Graham, H., McNeill, F., Raynor, P., Taxman, F.S. & Trotter, T. (Eds.). The Routledge Companion to Rehabilitative Work in Criminal Justice. Abingdon: Routledge.

Baier, D. & Dreißigacker, A. (2022). Straftaten älterer Menschen – ein Überblick. In: Pohlmann, S. (Ed.). Alter und Devianz, 53–69. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer.

Bennefeld-Kersten, K., Lohner, J. & Pecher, W. (eds.) (2015). Frei Tod? Selbst Mord? Bilanz Suizid? Wenn Gefangene sich das Leben nehmen. Lengerich: Pabst Science Publishers.

Bindler, A. & Hjalmarsson, R. (2017). Prisons, recidivism and the age–crime profile. Economics Letters, 152, 46–49.

Bruggencate, T., Luijkx, K. & Sturm, J.A. (2018). Social needs of older people: a systematic literature review. Ageing and Society, 38(9), 1745–1770.

Bundeskriminalamt (n.d.). Polizeiliche Kriminalstatistik (PKS). https://www.bka.de/DE/AktuelleInformationen/StatistikenLagebilder/PolizeilicheKriminalstatistik/pks_node.html.

Cadet, N. (2021). An ageing client base: How can probation deliver support for older service users? British Journal of Community Justice, 17(2), 119–133.

Clinks & Recoop (2021). Understanding the needs and experiences of older people in prison. London: Clinks.

Crawley, E.& Sparks, R. (in press). Age of Imprisonment. Willan Publishing.

Crewe, B., Goldsmith, A., & Halsey, M. (Eds.) (2022). Power and Pain in the Modern Prison: The Society of Captives Revisited. Oxford: University Press.

Diekmann, A. (2009). Empirische Sozialforschung. Grundlagen, Methoden, Anwendung. Reinbek: Rowohlt.

Falkingham, J., Evandrou, M., Qin, M. & Vlachantoni, I. (2020). Accumulated life course adversities and depressive symptoms in later life among older men and women in England: A longitudinal study. Ageing and Society, 40(10), 2079–2105.

Farrall, S. (2022). Rethinking what works with offenders. New York: Routledge.

Farrington, D.P., Kazemian, L. & Piquero, A. (Eds.) (2019). The Oxford Handbook of Developmental and Life-Course Criminology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fazel, S., Ramesh, T., Hawton, K. (2017). Suicide in prisons – an international study of prevalence and contributory factors. The Lancet Psychiatry, 4, 946–952.

Fischer, U. & Levenig, M. (2021). Bürgerschaftliches Engagement zwischen individueller Sinnstiftung und Dienst an der Gesellschaft. In: APuS – Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte; bpb.de.

Ghanem, C., Hostettler, U., & Wilde, F. (Eds.) (2023). Alter, Delinquenz und Inhaftierung – Perspektiven aus Wissenschaft und Praxis. Wiesbaden: Springer.

Ginnivan N. A., Chomik, R., Hwang, Y. I. J., Piggott, J., Butler, T. & Withall. A. (2022). The ageing prisoner population. International Journal of Prisoner Health, 18(4), 325–334.

Global Prison Trends (2022). Report –Penal Reform International & Thailand Institute of Justice. Penal Reform International.

Görgen, T. (2022). Alter und Strafvollzug. In: Pohlmann, S. (Ed.). Alter und Devianz, 227–239. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer.

Görgen. T. & Textores, L. (2023) Delinquenz im höheren Lebensalter. In: Ghanem et al. (Eds.). Alter, Delinquenz und Inhaftierung – Perspektiven aus Wissenschaft und Praxis, 3–20. Wiesbaden: Springer.

Greene, M., Ahalt, C., Stijacic-Cenzer, I., Metzger, L. & Williams, B. (2018). Older adults in jail: high rates and early onset of geriatric conditions. Health Justice, 6, 3.

Gruener, T. & Pohlmann, S. (in press). Age bias in the Perception and Assessment of Crime. Submittet in: Social Challenges in Social Sciences.

HMIPS (Her Majesty's Chief Inspector of Prisons for Scotland) (2017) Who Cares? The Lived Experience of Older Prisoners in Scotland's Prisons. Edinburgh: HMIPS.

Hammerschmidt, P., Pohlmann, S. & Sagebiel, J. (Eds.) (2014). Gelingendes Alter(n) und Soziale Arbeit. Neu Ulm: AG Spak.

Heidenblut, S. & Zank, S. (2010). Entwicklung eines neuen Depressionsscreenings für den Einsatz in der Geriatrie. Development of a new screening instrument for geriatric depression. Zeitschrift für Gerontologie und Geriatrie, 43 (3),170–176.

Heidenblut, S. & Zank, S. (2014). Screening for Depression with the Depression in Old Age Scale (DIA-S) and the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS15). The Journal of Gerontopsychology and Geriatric Psychiatry, 27(1), 41–49.

Herschbach, P. (2002). Das „Zufriedenheitsparadox” in der Lebensqualitätsforschung. Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik, Medizinische Psychologie, 52(3/4), 141–150.

Humblet, D. (2021). The Older Prisoner. Springer Nature.

Kenkmann, A., Erhard, S., Maisch, J. & Ghanem, C. (2020). Altern in Haft – Angebote für ältere Inhaftierte in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Kriminologie, 1, 101–122.

Kheirbeck, R.E. & Beamer, B.A. (2022). Incarcerated older adults in the coronavirus disease 2019. Public Policy & Aging Report, 32(4), 149–152.

Konrad, N. (2002). Suizid in Haft – europäische Entwicklungen unter Berücksichtigung der Situation in der Schweiz. Schweizer Archiv für Neurologie und Psychiatrie, 153(3), 131–136.

Langendorff, G. (2015). Lebensältere Gefangene im Strafvollzug in Deutschland und in den Bundesländern. Forum Strafvollzug, 64, 1, 8–10.

Kunz, F. & Gertz, H.-J. (Eds.) (2015). Straffälligkeit älterer Menschen. Heidelberg: Springer.

Loeber, R. & Farrington, D.P. (2014). Age-Crime Curve. In: Bruinsma, G., Weisburd, D. (eds) Encyclopedia of Criminology and Criminal Justice. Springer, New York.

Maelicke, B. & Wein, C. (Eds.) (2020). Resozialisierung und Systemischer Wandel. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

Maguire E., Atkin-Plunk C., Wells W. (2019). The effects of procedural justice on cooperation and compliance among inmates in a work release program. Justice Quarterly, 17 July.

Marti, I. (2020). A ›Home‹ or ›a Place to Be, But Not to Live‹: Arranging the Prison Cell. In: J. Turner & V. Knight (eds.). The Prison Cell, 121–142. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Matsching, T., Frühwald, S., Frottier, P. (2006): Suizide hinter Gittern im internationalen Vergleich. Psychiatrische Praxis, 33, 6–13.

Merkt, H., Haesen, S., Meyer, L., Kressig, R. W., Elger, B. S. & Wangmo, T. (2020). Defining an age cut-off for older offenders: a systematic review of literature. International journal of prisoner health, 16(2), 95–116.

Nikolaus T., Specht-Leible N., Bach M., Oster P., & Schlierf, G. (1994). Soziale Aspekte bei Diagnostik und Therapie hochbetagter Patienten. Erste Erfahrungen mit einem neu entwickelten Fragebogen im Rahmen des geriatrischen Assessment. Zeitschrift für Gerontologie und Geriatrie, 27, 240–245.

Opitz-Welke, A., Konrad, N., Welke, J., Bennefeld-Kersten, K., Gauger, U. & Voulgaris, A. (2019). Suicide in older prisoners in Germany. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 154.

Oswald, S. (2022). Der Weg nach draußen – Wiedereingliederungshilfe für ältere Gefangene. In: Pohlmann, S. (Ed.). Alter und Devianz, 318–326. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer.

Pohlmann, S. (2016). Altershilfe. Band 1: Hintergründe und Herausforderungen. Neu Ulm: AG Spak.

Pohlmann, S. (2022) (Ed.). Alter und Devianz. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer.

Pohlmann, S. (2023a). Wieder in Freiheit – Strafempfinden älterer Strafentlassener. In: Ghanem, C., Hostettler, U., & Wilde, F. (Eds.). Alter, Delinquenz und Inhaftierung – Perspektiven aus Wissenschaft und Praxis, 239–256. Springer.

Pohlmann, S. (2023b). Allen Widrigkeiten zum Trotz – vom Alter lernen. ProAlter, 4(23), 58–60.

Pohlmann, S. (ed.) (2002). Facing an Ageing World – Recommendations and Perspectives. Regensburg: Transfer.

Pohlmann, S. (in press). Angemessene Strafzumessung und Resozialisierungsoptionen im Alter. Submitted in: Neue Praxis.

Pruin, I. (2017). Die Gestaltung der Übergänge. In: Cornel, H.; Kawamura‐Reindl, G.; Sonnen, B.‐R. (eds.). Handbuch Resozialisierung, 572–590. Baden‐Baden: Nomos.

Ramsbrock, A. (2020). Geschlossene Gesellschaft. Das Gefängnis als Sozialversuch – eine bundesdeutsche Geschichte. Frankfurt/Main: Fischer.

RKI – Robert Koch-Institut (2022). Journal of Health Monitoring. Gesundheitsverhalten und depressive Symptomatik: Veränderungen in der COVID-19-Pandemie. Berlin: RKI.

Schäfer, L. & Kupka, K. (2021). Freiheit wagen – Alternativen zur Haft. Frankfurt: Lambertus.

Schlieter, K. (2011). Knastreport – das Leben der Weggesperrten. Frankfurt/Main: Westend.

Seddig, D. & Reinecke, J. (2017). Exploration and explanation of adolescent self-reported delinquency trajectories in the CrimoC study. In: Blokland, A. & van der Geest. V. (Eds.), The Routledge International Handbook of Life-Course Criminology, 159–178. London, New York: Routledge.

Sen, A. (2000). Ökonomie für den Menschen. Wien: Hanser.

Spiess, G. (2022). Methodische Herausforderungen altersdifferenzierter Kriminalitätsstatistiken. In: Pohlmann, S. (Ed.). Alter und Devianz, 37–52. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer.

Stöver, H. & Weyl, W. (2023). Pflege und Gesundheitsversorgung für ältere Menschen im Justizvollzug. In: Ghanem et al. (Eds.). Alter, Delinquenz und Inhaftierung – Perspektiven aus Wissenschaft und Praxis, 329–348. Wiesbaden: Springer.

Steffensmeier, D. J., Kramer, J., & Ulmer, J. (1995). Age Differences in Sentencing. Justice Quarterly, 12(3), 583–602.

Steffensmeier, D. J., Lu, Y. & Na, C. (2020). Age and Crime in South Korea: Cross-National Challenge to Invariance Thesis. Justice Quarterly, 37(3), 410–435.

Sudholt, E. (2022). Die Dauer der Schuld. Reportagen, 62, 70–91.

Suhling, S. & Greve, W. (2009). The consequences of legal punishment. In M. E. Oswald, S. Bieneck & J. Hupfeld-Heinemann (Eds.)., The social psychology of punishment of crime, 405–426. Chichester, UK: Wiley.

Suzuki. M. & Otani, A. (2023). Ageing, institutional thoughtlessness, and normalisation in Japan’s prisons. International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice. Online publication

Taylor, S. G., Eisenbarth, H. Sedikides, C. & Alicke, M. D. (2020). Explaining the better-than-average effect among prisoners. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, Volume51, Issue2, 90–106.

Tuichievna, M. O., Abdukhamidovna, N. M. & Rasulovna, K. B. (2023). Risk Factors for the Development of Diseases in Old Age and their Prevention. Research Journal of Trauma and Disability Studies, 2(3), 15–21.

Turner M., Peacock, M., Payne, S., Fletcher, A. & Froggatt, K. (2018). Ageing and dying in the contemporary neoliberal prison system. Social Science and Medicine, 212, 161–167.

Wahidin, A. (2006). No problems – old & quiet: Imprisonment in Older Life. In: Wahidin, A. & Cain, M. (Eds.) Ageing, Crime & Society, Chapter 11. Cullompton: Willan.

Wareham, C. S. (Ed.) (2023). The Cambridge handbook of the ethics of ageing. New York: Cambridge.

WHO – World Health Organisation (2002). Active ageing: A policy framework. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/67215.

Author´s

Address:

Prof. Dr. Stefan Pohlmann

University of Applied Sciences Munich

Am Stadtpark 20, D-81243 Munich, Germany

+49(0)8912652300

pohlmann@hm.edu

https://sw.hm.edu/kontakte_de/phonebook_detailseite_779.de.html