The Tapestry of Social Care Work History: A Pointillism Approach

Kara O’Neil, Leuphana University

Abstract: This paper <postulates that the understood ‘early history’ of social care work must be re-evaluated using methodology intended to deconstruct, decolonize, and delineate historical events from the current, common patriarchal influence of modern teachings. This paper disagrees with a history of social care work that too narrowly focuses on several male theorists of social care work but only a few pioneering female practitioners, resulting in a gendered bias of social care history. Previous historical methodologies have left social care work bereft of inclusivity and without a thorough investigation of the epistemological base of social care work(s) prior to professionalization. A more advanced history of social care work requires a new approach to historical documents which attempts to build or construct a more inclusive historical base of social care work. The Pointillism Approach offers a step-by-step model with which social care work historians can re-analyze and reinterpret important events in the development of social care work by evaluating hegemonic paradigms of care-work foundations.

Keywords: Social work; social care work; social pedagogy; sociology; inclusivity; antenarrative history; feminism, collective consciousness; internal bias

Introduction

"I draw on this method, because along with some feminists, I wish to challenge conventional research methods, epistemologies, pedagogical practices and writing style … I believe that the implication for feminist research is not only a contribution to both theory development, method and writing style, but also to pedagogy – how can we engage with the material, how can we learn, and what can we learn from these women?" (Williams 2020a pp. 67 - 68).

While it is commonly understood that social work as praxis began in the United States, England, and German-speaking Europe in the late 19th century with the Charity Organization Societies and friendly visitors (Chamberlayne, 1988; Trattner, 1999; Katz, 1996; Agnew, 2004; Hering, 2014), this paper postulates that social care work as a generalized theory developed much more broadly, eventually producing professional praxes which encompass social work, social pedagogy, community development work, childcare and education work, intervention work, etc.; and that while social care work may be considered ‘a thin concept’ (Cameron, Moss, Petrie 2021), these deficiencies in the definition or strength of the phrase are a result of lack of interdisciplinary understandings of care work through history, which has resulted in an incomplete and untheorized epistemic base.

This paper postulates that the taught history of social care work – to include social work, social pedagogy, adult education, early childhood education, prison reform, addiction care, and more – is reductive and somewhat fragmented. This paper disagrees with a history of social care work that too narrowly focuses on several male theorists of social care work but only a few pioneering female practitioners, resulting in a gendered bias within the historical narrative. The understood ‘early history’ of social care work must be re-evaluated using methodology intended to deconstruct, decolonize, and delineate historical events from the current, common patriarchal influence of modern teachings. As with many disciplines and professions, the history of social care work has been greatly reduced and minimized in modern teaching so that its current framework reflects primarily male influence. (It must be noted here that the use of ‘male’ and ‘female’ as identifiers is not intended to exclude individuals on the gender spectrum, but is merely intended to portray the paradigm of gender binary commonly recognized through historical narratives of the time; ‘men’ and ‘women’ are used in this paper to refer to those mentioned as they have been previously identified during the time in history in which they are presented.) Researchers must be careful of the influence of internal bias or collective consciousness as a result of patriarchal influences on the historical narratives which reflect the epistemic base of social care works. In fact, as King (2012) reminds us,

“The ideal of ‘scientific’ historical writing on the part of disinterested professionals was never impartial” as the “…normative nineteenth-century vision of historical production, as Bonnie Smith has persuasively argued, framed not only the type of history worth writing and determined its research methods, it also elected a chosen few – privileged, elite males – to be its most capable practitioners. Historical research and writing was ‘manly’ work, and women were dismissed as incapable or uninterested in its pursuit" (p. 18).

In this paper I will briefly problematize the common use of methodologies such as frame analysis, critical discourse analysis, and social movement theory as a means of constructing epistemological bases of social care works, and instead encourage the reader to engage in a more cross-disciplinary, inclusive means of re-analyzing ‘known’ historical ‘facts’ and reimagining epistemic narratives. Pulling from Kristin Williams’ (2020) feminist critical historiography and Kathrin Braun's (2015) work on the analysis of framing, the Pointillism Approach introduces a map by which analysts may re-evaluate texts, discourses, and events in the timeframe which predate the professionalization of social work and social pedagogy that have contributed to an early epistemic of social care work.

The Taught History of Social Care Work as Problematic

Sociology has historically been understood as the study of social problems, social relations, and social interactions. How the development of sociology as an academic discipline has been taught has generally framed the epistemic understandings of many praxes of social care work(s), and is a narrative that holds incredible influence over how the early development of social care work is understood. In the great paradox of human reasoning, how early social care work is understood holds incredible influence over how it continues to be perpetuated and understood. This historical narrative of care works cannot be fully considered without acknowledgement of influence from sociology as an academic discipline. Prior to the establishment of the disciplines in Western culture, terms relating to social care work - such as social work, social pedagogy, and sociology - began to shift and diverge from country to country, conceptualized relative to the culture and needs of the practice area. “This beginning period was followed by a paradigm ‘based on [the] authority of expert consensus and tradition’” (Jindra, 2017, p. 6), established primarily in German-speaking Europe. However, the wording of ‘expert consensus’ matters when the acknowledged ‘experts’ in question are too often predominately men and include little to no indication of the contribution of women within the field.

Ellwood (2019/1913) wrote in one of the first, and certainly one of the most well-known textbooks of sociology, Sociology and Modern Social Problems:

“It has been largely the agitations of the socialists and other radical social reformers which have called attention to the need of a scientific understanding of human society. The socialists and other radical reformers, in other words, have very largely set the problem which sociology attempts to solve," (pp.13 – 14).

In addition, Schwartz (1997) argued that:

"…’industrial problems, political problems, educational problems, and all other social problems must be viewed from the collective or social standpoint rather than simply as detached problems by themselves.’ The urge to achieve such a standpoint rendered one a sociologist, not a socialist.” (p. 288)

And that:

“One could argue that the individuation of ‘social problems,’ often at the hands of activist Anglo-American women, ran in parallel with a feminized concern for society’s multiple effects upon a sensitive self in need of healing and harmony” (Schwartz, 1997, p. 287; emphases added).

This language of “Anglo-American women” and “other radicals” offers little insight into who comprised these populations of women, and how or why their work contributed to social care work in a much greater capacity than currently appears. The history of social care work is not exempt from the phenomena “…that women receive little or no attention in traditional history writing, but even among radical and socialist historians they are all too often mentioned as an afterthought if at all, tagged on rather than present in their own right,” (Alexander & Davin, 1976, p. 4). As recently as 2022, texts have been published with bold, but perhaps not entirely factual, statements which acknowledge that, “…the social work profession was slow to take up feminist theory” (Epstein et al., 2022, p77). The seeming ‘ultimate’ goal of these texts, intended to encourage and facilitate feminist theories of social work, are necessary, important, and fully supported within this paper. However, statements such as these, innocuously made, continue to echo the neo-liberal agenda of social work education as they fail to recognize major events and contributors to the discourse and foundation of social care work.

If, as noted by Miehls and Moffat (2000), “The development of the social work identity has been long held as a central component in the training of social work students (Reynolds, 1942; Towle, 1952; Bandler, 1960; Kaplan, 1991; Memmot and Brennan, 1998)” (p. 340), then the perception of the individuals responsible for writing the texts which are now upheld as the 'archives' of social care work must be critically considered. Those reading and interpreting said archives are also influenced by their perceptions (Ben-Zeev, 1988). When both those writing and those reading are too similar in background, education, experience, and other socio-economic and political markers, the analyses provided become nothing more than an 'echo chamber' which reproduces hegemonic narratives (Smith, 1974). The stories people tell regarding how social care work has developed – the epistemics people accept and reproduce – continue to affect the development of social care work. Resources written by those who perceived the world in a different manner than the hegemonic elite who controlled the writing, publishing, and teaching of texts – which would ultimately culminate in new professions - were too often ignored and discredited, limiting even the possibility of rigorous and useful analysis (Lutz, 1990). This is problematic as a history built with limited narratives brings disadvantages for a truly evolved discipline.

To illustrate this point, take for example, Albion Small and George Vincent, prominent figures in the historical development of sociology as a recognized discipline (Buxton & Turner, 1992, p. 382). “Albion Small was a central figure in the organization of the [American Sociological Association] and therefore his views on women are particularly relevant” (Deegan 1981, p. 15). Small notably believed that a woman’s place was in the home, that women should not be taught to compete, personally or professionally, and that women should not be allowed to be breadwinners (Deegan, 1981, p.15). With such bigotry gatekeeping the burgeoning professions in social care work - which were often either lent credibility or labelled as nonsensical at the whims of ‘modern’ sociologists - it’s no surprise that women working in the field of social care work (often in areas which could be considered ‘applied sociology’) were not to be considered ‘sociologists.’

It is important to note that this misogyny and erasure is not limited to the annals of history, but exist still in works like Peter Burke’s History and Social Theory, which is considered an important classroom text. As Ahlkvist (2007) notes in his critique of Burke’s work:

“Despite its strengths, there are two aspects of Burke's book that sociology instructors should be concerned about. First, there is little discussion of women as either the producers or subjects of social theory and historical research. Second, Burke's preference for brief summaries of a large number of historical studies from various times and places over more detailed discussions of a smaller number of cases may frustrate sociologists who are likely to be unfamiliar with at least some of these historical examples” (p. 193).

These aspects, that of women as producers of social theory and missing diversity, show a distinct lack of social sustainability in the historical narratives of both sociology and social work, which have been perpetuated from the late nineteenth century and persist today.

Small’s classifications of ‘sociologist’ clearly pre-date Schwartz’s definition by over a century, but the point can be clearly argued that these understandings of who could be a ‘sociologist’, what was ‘applied sociology’, and who could be considered a ‘social worker’ were assigned, in part, as a result of the power paradigms of the time, echoed through history. This in spite of the fact that the women of the first conference of the International Congress of Women met in 1888, and published hundreds of pages of meeting minutes which showed a clear debate regarding the ‘social problems’ as viewed from a ‘collective standpoint’ 6 years prior to Small and Vincent’s publication of the 1894 textbook An Introduction to the Study of Society (Schwartz, 1997; ICW Report, 1888).

Problematizing Methodology

Methodology matters

Current methodologies and approaches to how historical narratives are written are not impervious to these patriarchal, exclusive imprints. Previous historical narratives regarding the development of social care work have been heretofore bereft of inclusivity and without a thorough investigation of the epistemological base of social care works prior to professionalization. A more advanced history of social care work requires a new approach to historical documents which attempts to build or construct a more inclusive historical base of social care work. In agreement with Anastas’ (2014) postulation that there is more than one possible contemporary epistemology that can support a ‘science of social work’ (p. 573), historians must explore a broader inclusion of events which occurred in history, parallel to that of Jane Addams’ settlement house movements and literary achievements, Mary Richmond’s compendium literary and practical works, and Alice Salomon’s educational outreach efforts. While the history and work of these women should not be understated, the narrative surrounding their work is often reductive, both limiting history to these 'primary' actors, and overly romanticizing their contributions (they did all and enough).

Interpretation of historical data must be ontological, ethnographical, and biographical. If empirical data is, “…anything for which a science has a protocol of decidability” (Fuchs & Plass 1999, p. 271) then there is not yet an agreed upon methodology (protocol of decidability) for reconstructive social care work history. By re-analyzing normative understandings of the development of the professionalization of sociology, social work, social pedagogy, and other social care work fields, the narrative of social work reconstructs into a more inclusive picture. An inclusive reconstruction of the history, and subsequent development of epistemology, requires that normative understandings of the development of the professionalization of sociology, social work, social pedagogy, and other social care work fields, be re-analysed and, when necessary, refuted. However, this is equally true regarding empirical understandings of social care work as even the most mundane description of a historical event carries the weight of the perception, bias and experiences of those making the claims. This paper is not intended as a review or critique of the following methodologies, per se, but rather a quick problematization of these methods as single-use approaches to the development of a new narrative of social care work.

Frame Analysis

One methodology frequently used for assessing important events is that of frame analysis, an important tool for unpacking relations between a historical event and how that event is understood in later times. While this method can be a powerful complement to archival research, ultimately the point is to determine what factors about or within an event constitute meaning in a historical setting. However, what is considered ‘important’ to any one researcher is subjective, rendering frame analysis subject to potential problems in accuracy and validity. In essence, frames are based on perspectives, and perspective alone cannot be used or determined as valid in analysis of historical events – there must be a deeper, or possibly a less subjective, means of analyzing such moments. Again, who is lauded as an ‘expert’ matters greatly here. This is to say that while a frame analysis can absolutely supplement the construction of a historical narrative, the repetition of hegemonic perspectives, which simply reproduce analyses, can become dangerous. To illustrate with Pointillist art theory, one may say: a field of blue dots gives the image of ‘blue’ without depth, but the addition of green, yellow, or white dots can bring the viewer to imagine water or clear skies. The picture cannot be completed without the blue dot, but other colors are absolutely necessary, even when not the primary focus of the viewer. This is also true regarding the relation of one analysis to another; it is the complement of many approaches which produces the greater clarity.

Critical Discourse Analysis

While discourse analysis is also critically important, the often-used method of Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) can be limiting. CDA aims to interpret past realities rather than hold space for a plurality of interpretations possible within the reality of historical memories. CDA is a necessary tool for historical analysis as, “…social interactions cannot be fully understood without reference to the discourses that give them meaning. As discourse analysts, then, our task is to explore the relationship between discourse and reality.” (Phillips and Hardy, 2002, p. 3) However, while the narrative may be interpreted using CDA, the story cannot be told through this method alone. This is to say that critical discourse analysis, by narrowing its scope too often to written texts, often fails to recognize the "cultural memory" derived from oral traditions and storytelling easily overlooked in text analysis. Historians may be able to interpret what ‘happened’ during the event, from the text, but what additional data is needed to understand the emotions, impetus, and thought behind the identified actions? Thus, while it is critically important to analyze the texts available, as a methodology for furthering insight and inclusivity within the field of social care work history, discourse analysis is also both useful and limited.

As Repina (2017) argues, “The content of the collective memory changes in accordance with the social context and practical priorities” (p. 334), which means that the relationship between the discourse reported and the ‘reality’ presented in modern histories of social care work are unreliably marred as a result of current social understandings of the male-dominated development and professionalization of social care work fields. In addition, discourse analysis, by the sheer nature of the methodology, lends to a narrative chronotype which is "the construction of plot and order" (Czarniawska 1997, p.11) and becomes, by default, reductive.

Organization and Social Movement Theory (framing analysis within social movement theory)

Social movement analysis also cannot offer a full and inclusive view of the impact of important events on or within the developing epistemology of social care work. History-theorists have argued ‘traditional’ social movement theory as problematic even within normative analyses of historical events. However, it is especially important when dealing with feminist reconstruction to note the class reductionism in Marxism for analysis of collective action. “Marxism’s class reductionism presumed that the most significant social actors will be defined by class relationships rooted in the process of production and that all other social identities are secondary at best in constituting collective actors” (Buechler, 1995, p. 442).

As “gendered notions were woven into the very fabric of the research process itself” (King 2012, p.18), it seems quite clear that traditional social movement theory is problematic for inclusive historical analysis. ‘Newer’ social movement theories were meant to offer a less exclusive methodology by, ironically, including more analysis of symbolic actions, processes, values, and social constructions in the development of social movements. However, these means of analyses, while well intentioned, are still exclusive of the women inherent in the myriad of social movements (Foreman 1998 & 2016). Nonetheless, analysis regarding the organization of important events in social care work history can offer a deeper understanding of the process behind the work, and potentially some insight into the thought behind the action.

A Pointillism approach to epistemology

Why Pointillism?

“Do you see? We have only two choices. We can believe, stubbornly, that the picture on the wall is whole. Or we can imagine Seurat as a boy, holding a fresh brush in his hand, thinking, ‘I will show them how easily they are tricked,’ then narrowing the tip with his mouth.” (Gehrke, 2002, p. 684)

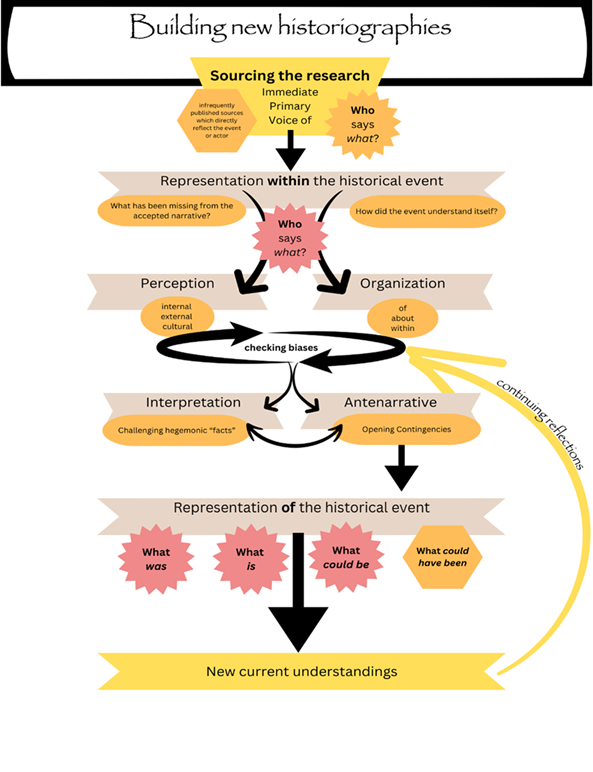

Pointillist Art was developed by the famous Impressionist era artist, Georges Seurat, as a means of pushing the development of art with the addition of scientific theory (Venturi, 1941). Pointillism engaged theories of color, refraction, and perception, offering viewers a means of reconstructing and re-analyzing art. Although “… a simplistic system of optical mixture, based on the primary colors alone, was never Seurat’s goal” (Broude, 1974, 581), the mechanics of the method act as a powerful analogy for approaching historical research and analysis. The Pointillism Approach to social care work history is a model of antenarrative, post-positivist historical reconstruction built with the intention of challenging current accepted paradigms of leadership or epistemology upheld in modern teachings of social care work development. The Pointillism Approach is not intended to replace methodologies but rather act as a model that may encourage and guide reflective practices which offer more inclusive and critical analyses of historical events through a compendium of methodologies and approaches to narrative-building.

“Impressionists were well aware that what they painted was not reality, but the appearance of reality.” (Venturi, 1941, p.36) Historians are often aware of the same. ‘History’ is an intangible fluid entity of ‘truth’ which assumes much and reproduces even more. Thus, while it is necessary that we learn and teach from our history in humanity, it is dangerous to teach that which has not been challenged, as it may propagate ideologies which are more hurtful than helpful. The Pointillism Approach offers a step-by-step model with which social care work historians can re-analyze and reinterpret important events in the development of social care work by evaluating not only hegemonic paradigms of care-work foundations, but also their personal biases and modern societal norms which influence and control our understandings of ‘truth’.

Critical historiography, antenarrative histories, and the Pointillism Approach

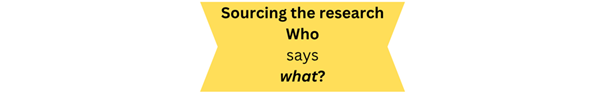

Sourcing the research

Pointillism Approach: Sourcing the research

Critical historiography requires that researchers first broaden their understanding of 'acceptable' sources – as already reflected in the increasing acceptability of ethnographic sources within social science fields. This acceptability of 'other' or 'new' sources is pertinent to building a more epistemically valid understanding of social care work. Many historical analyses begin with an 'event', whether this be a conference, a biography (or autobiography), an archaeological discovery, or other 'significant' instance in history. The sources gathered are subjectively obtained, but ought to offer representation within historical events which refers to immediate, primary sources that describe, explain, or illustrate a critical event. An epistemological understanding of epistemics, however, requires that researchers critically engage from a more representational model of constructivism. “Taken all together, the primary frameworks of a particular social group constitute a central element of its culture…" (Goffman 1974, p. 27). Thus, the framing of an event influences the understood epistemic, which then affects the historical framing surrounding said event. Braun (2015) reminds the reader, however, of, "the possibility that dominant frames may precede and shape actors' perceptions, self-understandings and identities in ways that are not wholly transparent to them" (p. 449).

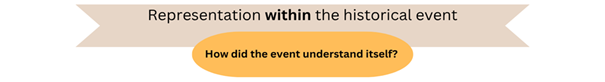

Representation within historical event

Pointillism Approach: Step 1

Naturally, primary sources are not always available. When this is the case, researchers must begin to apply a critical lens immediately, questioning their use of sources, the source authors or publishers, and the ready availability of sources. This is to say that the source(s) used must reflect a diverse population, differing voices, and perhaps 'ought' to be less readily accessible; readily accessible sources are the result of a pushed or previously accepted narrative, perpetuating the hegemonic ideal rather than examining a concurrent historical possibility. The argument that one must be careful not to simply echo or reproduce knowledge, but must consistently question and evaluate ‘truth’, is not singular to this paper (Cluxton & Horst, 2019; Teich, 2015; Williams, 2020). When ‘knowledge’ is simply reproduced, contingencies for broader understanding close. Primary source(s), then, become paramount as a means to offer a starting point to analyze how an event was represented at the time, by voices directly involved or directly watching said event (primary or secondary sources). This 'representation within' may include a singular source, such as an official event report, or several sources, such as a compilation of articles, biographies and autobiographies, and other pieces of data, that offer a Pointillist approach to storyline construction.

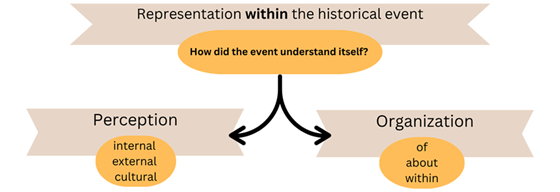

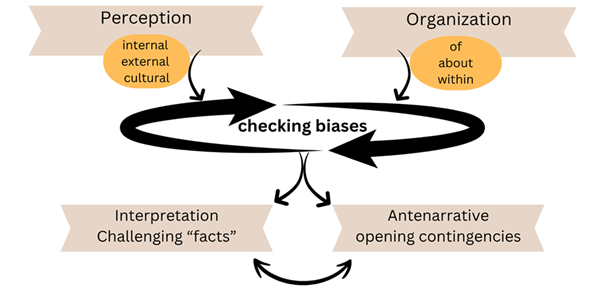

"I believe that making history actually happens in the present and it is a practice which should not only chase so-called facts, but examine their context, examine what has been collected, who collected it, and why it was collected and held as important or significant" (Williams 2020 p. 62). This context is the representational canvas of the Pointillism approach. As documentation from the past, primary source representation(s) of an event reside(s) in a perpetual state, thus, analysis must begin at the source point. The nearer to primary sources, the more powerful the voice of representation becomes. It is important that researchers be critically aware of who says what. Centering representation, the researcher then begins to apply Braun's pillars of perception, organization, and interpretation, which are inherent in how people "represent their knowledge of the world" (Braun 2015, p. 445). However, as stated above, simple analysis of these pillars is not solely sufficient for an inclusive analysis. Williams' approach through feminist critical historiography must be applied, as well.

Applying Feminist Critical Historiography to Braun’s pillars

I present an example of a researcher wishing to explore an event through a framework of a more traditional discourse analysis. Let me assume for a moment that the researcher is determined and interested in examining the number of times the phrase 'women's work' appears within a particular document. Naturally, it is quite possible to simply count these words and assign meaning to the number found. A network analysis may even examine the primary source for the number of times the phrase 'women's work' and the word 'social' appear within the same sentences in said document and assign meaning to these findings. However, while it is of course possible to assign a word to a ‘value’ and count the number of times said word appears, and to empirically quantify that word, one cannot then ‘prove’ what was meant by it. A rigorous historian may next attempt to analyze the meaning of said word by tracing its usage and understanding through history, assigning action to the word or phrases analyzed. Through this example of language analysis, the entire document is then assigned as the 'representation within'. The extrapolated data must then be analyzed through lenses which focus specifically on the perception, organization, interpretation, and representation of the data.

This application is applied in many small steps, as outlined first by Williams (2020b), and complemented by the model provided within this paper. Williams (2020b) states that, “feminist theorists need to be aware of the hidden subjectivities which are discursively at work to produce so-called normative (male) knowledge and patriarchal power relations” (pp. 242-243). In her dissertation (2020a), Williams offers a new approach to historical analysis which she coins as ficto-feminism, stating that, “ficto-feminism offers scholars the means to study lost female figures of significance, surface their lost lessons and contributions, uncover the discourses, which hide them from view, and rhetorically challenge the limited domain of current study with a defiantly feminist lens" (p. 7). This paper presents Williams' feminist critical historiography as relevant for a developmental understanding of the epistemology of early social care work.

First, the researcher must apply a critical feminist historiographical lens by: reflecting on possible personal bias; ensuring that the language being applied to conclusions and discussions embodies the voice of the actors taken from within the primary source – as well as considering the native language background, environment, and life situations which may have influenced that voice; and by offering an interrogation of power in each application. So, for example, when counting the number of times the phrase women's work is applied within a source, it must also be noted who used the phrase and what the phrase means to them (when possible to discover), and why the phrase was used. From this deconstruction, the analyst then gathers new or different bits of information – dots of color for the canvas – with which to begin construction of an antenarrative historiographical record.

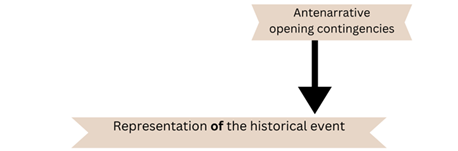

The idea of antenarrative writing was inspired by the language of 'living story', which argues that story, unlike narrative, "has no borderlines" (Jørgensen 2011, p. 288). This is absolutely vital, as storytelling, as opposed to narrative reproduction, "means to uphold the unfinished and open character of interpretations" (Jørgensen 2011, p.284). To write an antenarrative is not to write an anti-narrative – a story with no clear line of argumentation or chronological application – but to paint a clearer picture of an already existing narrative by offering parallel lines of argumentation, open-ended possibilities for alternative movements, and a recognition of the inability to construct a full or absolute unbiased ‘truth’ in narrative.

Pointillism Approach: Step 2

Perception

Perception of the meaning of each word or phrase would need to be analyzed not only with a critical lens regarding each individual use of the word within the text and by the actors, but also with a careful 'examination of one's own position' by the researcher. This requires humility and self-reflection. In addition, researchers must consider how the meaning of the phrase or word is perceived through their personal bias, and why that perception is present. Perhaps the researcher considers 'women's work' to be a phrase which denotes a demeaning of worth or effort. While this is a modern, socially accepted understanding of the phrase, such modern bias cannot be reasonably applied within interpretation of historical data. There are moments in history where 'women's work' was considered as positive and constructive engagement with the local society, to include several aspects of care work which are today professional fields of care. Additionally, when considering global linguistic variety, claims to understand or assign 'meaning' to any given word or phrase become nothing short of hubris. Therefore, the variability for analysis using the assigned phrases or words as data used to illustrate a given value or social construction is too great to be reliable.

Organization

Continuing with this example, researchers must also reflect on their own organizational practices. Researchers must reflect on the reason(s) that certain organizational research models were chosen, the ideology behind the organization of one's research, and the chronology of research expectations. For example, a researcher may reflect on their justification for setting the boundary of 'women's work' and 'social' as needing to occur within the same sentence. They may ask what internal bias, prior experience, or assumed knowledge led the researcher to the determination that 'women's work' and 'social' may be closely enough related to one another to be analyzed in the manner determined. Every decision holds internal bias and, as such, every decision must be reflected upon.

Clearly, one cannot assess every word of a large corpus; selection is always subjective. Application of Williams' feminist critical historiography requires that reflection on practices be applied for every decision, which continues to interrogate power and engage in discursive understandings of how each analysis has been conducted, to disrupt normative thinking and hegemonic regurgitation. It is important to note that this is not a linear recommendation, but rather a circular movement of reflection, or hermeneutic circle (Macdonald & Pinar, 1995; Van de Ven & Chateau, 2025; Putra, 2023). Reflecting on one's perception may bring organization into question, and vice versa. Thus, this process must be revisited several times to ensure that biases are understood and accounted for within the best ability of the researcher before interpretation begins.

Pointillism Approach: Step 3

Interpretation

The newly critiqued perceptions, reflected on the organizational structure of the research, and vice versa, offer space for new understandings of events. Collected results must always be interpreted by the researcher, and placed into a storyline, report, or narrative – the most crucial aspect of any research. Interpretation of 'findings' requires a critical use of reflexivity. "The reflexivity element in auto-ethnography is about taking a critical perspective on our own process of writing, knowledge production and on our own position with respect to the subject of inquiry" (Styhre and Tienari, 2013 - as found in Williams, 2020b). The intention of personal reflection regarding the perception and organization of data is to assist the researcher in critically engaged interpretations of findings. This interpretation of findings then becomes, through writing, the new representation of the historical event being analyzed. This representation matters a great deal as it adds to the corpus of knowledge and can be an important tool in disrupting the hegemonic, normative narrative.

This reconstructive interpretive storyline writing may best occur within the above-mentioned antenarrative analysis framework in which the author resists placing events in a linear history as a before/middle/end sort of history but rather establishing an idea of the historical story which allows for multiple ‘truths’ and understandings to happen simultaneously, eliminating the possibility (and need) for one truth. It is here that the Pointillism analogy resurfaces. It is not necessary to brush findings together to build a new color of truth; each individual point is important and necessary. Once the canvas is covered, a picture emerges while maintaining the integrity of each individual dot. However, while there is the possibility of either more or alternative truths regarding the development of social care works through history, it remains necessary that the points of reference which illuminate these truths remain methodologically controlled and transparent in the scientific community. It is for this reason that I postulate the Pointillism Model as a potential approach to restructuring and re-analyzing the impact of events and people on this development.

Pointillism Approach: Step 4

The 'New' Historical Epistemology

This concept of a freedom to reimagine must be held firmly as findings are interpreted and shared, building a new framework which upholds the representation of the historical event being reviewed. "To emphasize the story instead of narrative means to uphold the unfinished and open character of interpretations" (Jørgensen 2011, p. 284). It is the compilation of dotted colors on a canvas of history which enables theorists to begin to establish a larger picture regarding the epistemology of social care work. Perhaps 'blue' dots emerge most clearly, as in Paul Signac's The Port of Rotterdam or the 'orange' of Henri-Edmond Cross' Les pins catches the eye. However, despite the orange domination, the blue in Les pins remains visible and obvious; the truth remains within, unblended, untainted, and worthy of closer review. This is no less true for the findings and interpretations of historical events. Rather, directly opposing the theory-ladder of prior social work history means disrupting the narrative and beginning to dot the canvas of history with colorful stories, intent on building a more cohesive picture without tainting the purity of the story simply to offer 'aid' to the viewer. It is important to also note Williams’ (2020b) acknowledgment that inclusivity requires historians make a conscious and deliberate attempt to make space for “non-traditional voices in theory while acknowledging the challenges that come from speaking for others” (p. 243). This sort of disruptive thinking is vital in reconstructing the history of social care work and teasing out an appropriately representative epistemology of care.

The language of modern social work is reflected in one such event, the International Congress of Women of 1888 (Report, 1888). Participants of the ICW 1888 clearly stated their desire to “view from the collective or social standpoint” (Schwartz 1997, p.228) the problems facing society. Yet, the ICW 1888 event remains relatively unknown and underappreciated as a significant event in the development of social care work. Therefore, the ICW 1888 may act as a case-study to situate the history of social care work within the well-documented phenomena of excluding women’s voices, works and contributions within several various fields throughout history (See: Repina 2017; Williams, 2020). Re-evaluation may offer a vastly different understanding of the early epistemologies and ideologies of social care work, which may in turn change the trajectory of current teaching and, as such, current epistemic of ‘care work.’

Pointillism Approach Model

References:

Agnew, Elizabeth (2004). From Charity to Social Work: Mary E. Richmond and the Creation of an American Profession. University of Illinois Press, Chicago.

Alexander, S., & Davin, A. (1976). Feminist History. History Workshop Journal, 1(1), 4–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/hwj/1.1.4.

Ahlkvist, J. (2007). Reviewed work(s): History and Social Theory by Peter Burke. Teaching Sociology, 35(2), 192-193.

Anastas, J. W. (2014). The Science of Social Work and its Relationship to Social Work Practice. Research on Social Work Practice, 24(5), 571–580. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731513511335.

Bandler, B. (1960). Ego-centered teaching. Smith College Studies in Social Work, 30 (2), pp. 125 – 136.

Ben-Zeev, A. (1988). The Schema Paradigm in Perception. The Journal of Mind and Behavior, 9(4), pp 487-513.

Braun, K. (2015). Chapter 23: Between representation and narration: Analysing policy frames. In Handbook of Critical Policy Studies (pp. 441–461). Edward Elgar Publishing, Inc.

Broude, N. (1974). New Light on Seurat’s “Dot”: Its Relation to Photo-Mechanical Color Printing in France in the 1880’s. The Art Bulletin, 56(4) pp. 581-589.

Buechler, S. M. (1995). New Social Movement Theories. Sociological Quarterly, 36(3), 441–464.

Burke, P. (2005). History and Social Theory. Ithaca, NY. Cornell University Press.

Buxton, W., & Turner, S. (1992). From Education to Expertise: Sociology as a “Profession.” In Sociology and its publics: The forms and fates of disciplinary organization (pp. 373–408). University of Chicago Press.

Cameron, C., Moss, P. & Petrie, P. Towards a social pedagogic approach for social care. IJSP. 2021. Vol. 10(1). DOI: 10.14324/111.444.ijsp.2021.v10.x.007.

Chamberlayne, P., Cooper, A., Freeman, R., Rustin, M. (1999). Welfare and Culture in Europe: Towards a new paradigm in social policy. Jessica Knightly Publishers, Ltd. London, England.

Czarniawska, B. (1997). Narrating the Organization: Dramas of Institutional Identity. University of Chicago Press.

Deegan, M. J. (1981). Early Women Sociologists and the American Sociological Society: The Patterns of Exclusion and Participation. The American Sociologist, 16(1), 14–24.

Ellwood, C. A. (2019/1913). Sociology and Modern Social Problems. Good Press.

Epstein, S., Hosken, N., & Vassos, S. (2022). Chapter 5: A Pedagogy of Our Own: Feminist Social Work in the Academy. In Rethinking Feminist Theories for Social Work Practice (pp. 77–96). Palgrave macmillan.

Foreman, A. (1998) Georgiana. Duchess of Devonshire. Harper Perennial.

Foreman, A. (Creator) (2015). The Ascent of Woman [television series]. BBC Documentary mini-series.

Fuchs, S., & Plass, P. S. (1999). Sociology and Social Movements. Contemporary Sociology, 28(3), 271–277.

Gehrke, S. (2002). The Invention of Pointillism. The Georgia Review, 56(3), 683-684.

Goffman, E. (1974). Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience. University Press of New England.

Hering, Sabine & Münchmeier, Richard. (2014) Geschichte der Sozialen Arbeit: Eine Einführung. Beltz Juventa, Weinheim und Basel.

ICW History. (n.d.). [..Com]. The International Council of Women Is the First Truly Global Women’s NGO Which Was Founded in 1888 for the Advancement of Women All over the World. Retrieved March 7, 2023, from https://www.icw-cif.com/history/.

Jindra, I. W. (2017). The emerging “science of social work” in the United States and German-speaking countries: A comparison. International Social Work, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872816682581.

Jobs.ie. (2023, August 16). What does a social care worker do? Jobs.ie. https://www.jobs.ie/job-talk.

Jørgensen, K. M. (2011). Antenarrative Writing—Tracing and Representing Living Stories. Routledge.

Kaplan, T. (1991). Reducing student anxiety in field work: Exploratory research and implications. The Clinical Supervisor, 9 (2), 105 – 117.

Katz, Michael B. (1996). In the Shadow of the Poorhouse: A Social History of Welfare in America. Library of Congress, New York, NY.

King, M. (2012). Working With/In the Archive. In Research Methods for History (pp. 13–29). Edinburgh University Press.

Lutz, Catherine (1990). The Erasure of Women’s Writing in Sociocultural Anthropology. American Ethnologist, 17(4), pp 611-627.

Memmott, J. & Brennan, E. (1998). Learner-learning environment fit: An adult learning model for social work education. Journal of Teaching in Social Work Education, 16 (1,2), 75-98.

Miehls, D. & Moffat, K. (2000). Constructing social work identity based on the reflexive self. The British Journal of Social Work, 30 (3), 339 – 348.

NiDirect. (2023, Sept 25). Careers in social care. Nidirect government services. https://nidirect.gov.uk/articles/careers-in-social-care.

Phillips, N., & Hardy, C. (2002). Discourse Analysis: Investigating Processes of Social Construction. Sage Publications, Inc.

Repina, L. (2017). Historical Memory and Contemporary Historical Scholarship. Russian Social Science Review, 58(4/5), 318–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/10611428.2017.1365546.

Report of the International Congress of Women. (1888). ProQuest Information and Learning Company.

Reynolds, B. (1942) Learning and teaching in the practice of social work, New York, Farrar and Rinehart.

Schwartz, H. (1997). On the Origin of the Phrase “Social Problems.” Social Problems, 44(2), 276–296.

Schugurensky, Daniel (2016). Social Pedagogy in North America: Historical Background and Current Developments. Pedagogia Social. Revista Interuniversitaria, 27 pp 225-251. DOI: 10.7179/PSRI_2016.27.11

Smith, Dorothy (1974). The Social Construction of Documentary Reality. Sociological Inquiry, 44(4) pp225-294.

Social Care (25 Sept 2023). Cambridge Dictionary. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/social-care.

Styhre, A., & Tienari, J. (2013). Self-reflexivity scrutinized: (pro-)feminist men learning that gender matters. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal, 32(2), 195-210.

Thempra (2023, 09, 24). What social pedagogy means. Thempra Social Pedagogy. https://www.thempra.org.uk/social-pedagogy/.

Towle, C. (1952) The learner in education for the professions. Chicago, IL. University of Chicago Press.

Trattner, Walter I. (1999). From Poor Law to Welfare State: A history of social welfare in America. The Free Press, New York, NY.

Venturi, L. (1941). The Aesthetic Ide of Impressionism. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 1(1), 34-45

Williams, K. (2020a). Conversing in time with overlooked, historical female proto-management theorists: A ficto-feminist polemic [Doctoral Dissertation]. Saint Mary’s University.

Williams, K. (2020b). Feminist critical historiography: Undoing history—A conceptual model. In Handbook of Research on Management and Organizational History (pp. 242–255). Edward Elgar Publishing, Inc.

Author´s

Address:

Kara O’Neil, MA (Doctoral Student)

Leuphana University

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2554-5018

oneil@leuphana.de