Social and Policy Responses to Maternal Mental Health: The Experiences of Primigravida Mother’s in India During COVID-19

Zuhdha Yumna Z., Bharathiar University

B. Nalina, Bharathiar University

Revanth R., PSGCAS

Abstract: This scoping review synthesises evidence on the mental health and maternity care experiences of primigravida women in India during the COVID-19 pandemic. Guided by Arksey and O’Malley’s (2005) framework and Braun and Clarke’s (2006) thematic analysis, 39 studies were reviewed to map key patterns. Seven interconnected themes emerged, with consistently reported psychological distress driven by anxiety, depression, and uncertainty. Disruptions to antenatal services and uneven access to telemedicine further limited care and heightened isolation. Community health workers played a critical supportive role, though their capacity was constrained by workload and resource shortages. Financial hardship and restricted access to welfare schemes additionally impeded care-seeking, particularly among socioeconomically disadvantaged women. Evidence on pandemic-specific maternal mental health initiatives showed mixed effectiveness and limited reach. Overall, the review indicates that COVID-19 intensified existing inequities and introduced new barriers to maternity care, underscoring the need for strengthened support systems, expanded digital access, and responsive social policies to protect maternal well-being in future crises.

Keywords: Primigravida mothers; Maternal mental health; COVID-19 pandemic; Antenatal care; India.

1 INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 pandemic emerged as an unprecedented global crisis, disrupting health systems livelihoods, and everyday life across the world. The World Health Organization emphasized the need for enhanced maternal mental healthcare during the pandemic, recommending the integration of mental health services into maternal healthcare to mitigate its impact on pregnant women (World Health Organization, 2020). Globally, the pandemic exacerbated existing challenges faced by pregnant women, with research indicating that anxiety and depression significantly increased during this period. A systematic review and meta-analysis revealed that the overall prevalence of anxiety among pregnant women was 42%, while depression was 25% during the pandemic (Arzamani et al., 2020). However, India faced particularly severe consequences due to its unique socio-economic landscape, healthcare infrastructure limitations and cultural factors. Prior to the pandemic, it was estimated that 10–35% of women in India suffered from depression during pregnancy and the postpartum period (Panolan et al.,2024). The uncertainty surrounding COVID-19 further intensified these concerns, with pregnant women experiencing social isolation, heightened fear of infection, and reduced access to health facilities.

Primigravida women are particularly susceptible to psychological distress, as they face the uncertainties of pregnancy without prior experience leading to elevated anxiety, greater worry about the future, and increased fear of childbirth (Kc et al.,2020 ; Kalra et al., 2021 ).These vulnerabilities were further intensified during the COVID-19 pandemic, when fear of infection, concerns about delivery and disruptions in prenatal services created additional stressors. Supporting this, a multicentric study conducted across five medical colleges in India reported significant generalized anxiety among pregnant women, driven by worries about contracting the virus, difficulties in accessing healthcare, and concerns for their infants’ well-being (Kalra et al., 2021). This discouraged many women from seeking timely medical assistance. A qualitative study found that over 60% of pregnant women faced difficulties in accessing healthcare services during the lockdown, with mandatory COVID-19 negative reports for hospital admission, unavailability of drugs and transportation challenges serving as major barriers (Shrivastava et al.,2021 ; Goyal et al.,2022 ).Within family settings, pregnant women faced increased domestic responsibilities, strained relationships and in some cases, domestic violence, further aggravating psychological distress (Chandra et al.,2020).

The loss of employment or reduced household income due to economic instability heightened financial stress, particularly for lower-income families, which in turn affected prenatal nutrition and access to healthcare (Gopalakrishnan et al.,2022; Tripathi et al., 2025). Recognizing the challenges of pregnant women, the Indian government has earlier implemented Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana (PMMVY) centrally sponsored scheme, designed to provide financial assistance during pregnancy to promote better health and nutrition for both mother and child all over India. Similar to the maternity benefit scheme in other low and middle income countries, Tamil Nadu state along with PMMVY scheme has integrated and introduced as Dr.Muthulakshmi Reddy Maternity Benefit Scheme in 2018. It is also a cash assistance scheme provided to Pregnant mothers, which uniquely serving first-time and second-time mothers providing a total of Rs.18,000 (Rs.14,000 cash assistance plus Rs.4,000 in nutrition kits) released in three installments (Jagannath et al., 2025). During Covid19, the Government took initiative to enroll all the eligible pregnant women to benefit from these schemes in order to mitigate their financial crises. In addition, Telemedicine services and digital healthcare platforms were expanded to facilitate remote consultations and mental health counseling for pregnant mothers (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW,2021). The National Mental Health Programme was expanded to include tele-counseling services for expecting mothers, while state-level initiatives incorporated community-based mental health interventions (Gundi et al., 2025). Despite these efforts, several challenges hindered the effectiveness of these initiatives. This paper aims to evaluate the social and policy responses to the mental wellbeing of primigravida pregnant mothers during COVID-19 in the Indian context, with a specific focus on understanding how existing government schemes and their implementation challenges affected first-time mothers. By analyzing the impact of these initiatives and identifying gaps and effectiveness, this scoping review seeks to provide evidence-based recommendations for enhancing maternal mental health policies and strengthening social support systems in future public health emergencies. Addressing this issue is crucial to ensuring holistic maternal care and preventing adverse mental health outcomes for both primigravida mothers and infants during and after the crisis.

2 REVIEW METHODS

This paper has adopted Scoping review Arksey and O’Malley’s (2005), design with special focus on India as the primary setting. Indian studies were prioritized for inclusion, given the country’s specific socio-economic and policy context. Global literature is drawn on selectively to provide context and points of comparison, but the core findings and analysis pertain to India. The population of interest is primigravida pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic. Relatively few studies disaggregate findings by parity, the review also considers studies on pregnant women more broadly, highlighting where results are explicitly relevant to or distinguishable for primigravida women.

2.1 Search Strategy

A comprehensive search was conducted to identify relevant literature exploring the social impact and policy measures affecting the mental well-being of primigravida pregnant mothers during the COVID-19 pandemic in India. The search was systematically conducted across prominent databases, including PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, ScienceDirect, Google Scholar, and BMC Public Health. The strategy aimed to capture a wide range of peer-reviewed articles, governmental reports, policy documents, and grey literature that provided insights into maternal healthcare challenges during the pandemic. A combination of keywords and Boolean operators was used to refine the search results. The primary search terms included: ("Primigravida" OR "first-time pregnant women") ("Maternal mental health" OR "psychological distress" OR "perinatal anxiety" OR "antenatal depression") ("COVID-19" OR "pandemic" OR "SARS-CoV-2 impact") ("Maternal healthcare accessibility" OR "antenatal care" OR "telemedicine for pregnant women") ("Government policies" OR "healthcare programs for pregnant women" OR "public health response").

The search strategy combined these terms using Boolean operators such as AND, OR, and NOT to narrow or broaden the search results as necessary. Filters were applied to include only open-access full-text articles, English-language publications, and studies published between 2020 and 2025 to ensure that findings were relevant to the pandemic period. Additional manual screening of reference lists in selected articles was performed to identify further relevant studies. The search results were imported into EndNote for reference management and duplicate records were removed before proceeding with the screening and selection process. PRISMA Chart was utilized to structure the inclusion and exclusion of articles, ensuring a rigorous and systematic approach to data extraction. This strategy enabled a comprehensive understanding of the barriers, policy gaps, and recommendations related to maternal mental healthcare for primigravida mothers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Table 1: Inclusion & Exclusion Criteria

|

Inclusion |

Exclusion |

|

Studies focusing on primigravida mothers during COVID-19. And articles comparing pre pandemic & pandemic maternal care. |

Studies focusing only on physical health outcomes. |

|

Studies examining mental health dimensions, experiences relating to social and policy responses . |

Case studies, opinion pieces, unpublished reports. |

|

Studies conducted in India and multi-country studies with clearly identifiable Indian data. |

Indian language publications were excluded for feasibility and consistency in interpretation. |

|

Studies published between 2020 and 2025 |

Articles lacking full text access. |

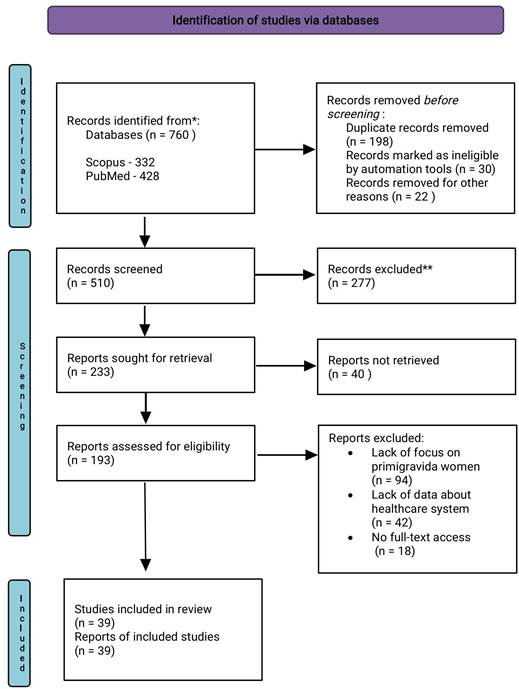

Figure 1: PRISMA Flow chart (Page MJ et al., 2021)

The initial database search across Scopus and PubMed yielded a total of 760 articles (Scopus: 332, PubMed: 428). After removing 198 duplicate records, 30 records marked as ineligible by automation tools, and 22 records removed for other reasons, a total of 510 articles remained for the title and abstract screening phase. During the screening process, 277 articles were excluded due to irrelevance to the research topic, leaving 233 full-text articles for further assessment. At this stage, 40 reports could not be retrieved, reducing the number of eligible full-text reports to 193. These studies were then reviewed against the inclusion and exclusion criteria, leading to the removal of 94 articles due to lack of focus on primigravida women,42 studies lacked the data on Healthcare system, and 18 articles were removed due to no full-text access.

As a result, 39 studies met all inclusion criteria and were included in the scoping review. These studies provided valuable insights into psychological distress among first-time pregnant mothers, disruptions in maternal healthcare, the role of telemedicine, gaps in mental health support, and policy recommendations for future public health crises. This step by step approach, guided by the PRISMA flowchart ensured a comprehensive and unbiased selection of studies, contributing to a deeper understanding of the social impact and policy measures affecting primigravida pregnant mothers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

3 RESULTS

The results of this scoping review synthesize evidence on the experiences of primigravida pregnant mothers during the COVID-19 pandemic in India. Following study selection and data charting, the extracted findings were systematically coded and organized using Braun and Clarke’s (2006) thematic analysis approach, which facilitated the identification of recurring patterns across the literature. This process led to the development of key themes that collectively capture the complex challenges faced by first-time mothers during the pandemic. These themes reveal how structural constraints, socio-economic pressures and disruptions within the healthcare system shaped maternal mental health and access to care. The following sections present these themes in detail, outlining the specific challenges encountered by primigravida mothers and the broader implications for maternal health systems during public health crises.

3.1 Psychological Distress of Primigravida Pregnant Mothers During COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic significantly increased psychological distress among primigravida mothers due to uncertainty, fear of infection, and disruptions in antennal services compounded the inherent anxieties of a first pregnancy (Coussons-Read, 2013; Amin et al., 2022). Globally, rates of anxiety and depression among pregnant women rose by 25–35% , compared to pre-pandemic levels of 10–15% (Lebel et al., 2020).This surge reflected the unique stressors introduced by COVID-19, including social isolation, healthcare restrictions, and concerns for maternal and fetal health.In the Indian context, several studies have echoed similar patterns of distress. Jungari and Singh (2020) highlighted that uncertainty surrounding the pandemic contributed to heightened depressive symptoms among pregnant and postpartum women. While a national survey by UNICEF (2021) revealed that approximately 60% of pregnant women, particularly in rural and low-income populations, reported severe stress and anxiety arising from inadequate social and healthcare support during lockdowns. Further, Bankar et al. (2022) observed significant elevations in anxiety and depression among perinatal primigravida mothers, directly linked to pandemic-related disruptions in antenatal visits and community healthcare services.

Primigravida mothers, lacking prior pregnancy experience, faced intensified stress due to social isolation, limited healthcare access, and hospital safety concerns (Yan et al., 2022). Studies in India have reinforced this vulnerability, Amin et al. (2022) found that nearly 80% of COVID-19-positive pregnant women reported mild to moderate depression. while Bachani et al., (2021) observed clinically significant anxiety among expectant mothers admitted for delivery during the pandemic. Basutkar et al. (2021) further reported that lockdown-induced isolation, financial strain, and lack of partner support substantially worsened perinatal distress, particularly among first time mothers. The consequences of such psychological strain are far-reaching. Research demonstrates that maternal stress and anxiety are associated with physiological changes that may increase the risk of pregnancy-induced hypertension, preterm birth, and low birth weight due to stress-related hormonal imbalances (Nath et al., 2021).

A meta analysis of 221,974 women reported the highest anxiety prevalence in the third trimester (24.6%) compared to earlier stages of pregnancy due to stress as delivery approaches (Dennis et al., 2017; Choedon et al., 2023). Beyond medical risks, poor maternal mental health can also impair maternal-infant bonding and negatively impact fetal development and long-term child well-being (Pankaew et al., 2024). Additional fear prevailed during COVID19 was potential vertical transmission, uncertainties about vaccine safety and limited family or institutional support further heightened distress, especially among first-time mothers (Chen et al., 2020). Brooks et al. (2020) emphasized that lockdowns and prolonged social isolation magnified psychological distress among vulnerable populations. A trend mirrored in Indian studies too, depression and anxiety among women in their first or third trimesters and among low-income households were higher (Amin et al., 2022). Given the pivotal role of maternal mental health in fetal and neonatal outcomes, addressing psychological distress among primigravida women during public-health crises is essential. Integrating mental-health screening into routine antenatal care, promoting digital counseling services, and developing community-based psychosocial support networks can help safeguard maternal well-being in future pandemics.

3.2 Healthcare Disruptions and Prenatal Care Accessibility

The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted healthcare systems worldwide, severely affecting the accessibility and quality of prenatal care services for pregnant women, particularly primigravida mothers. Lockdowns, movement restrictions and healthcare resource reallocations to pandemic response efforts led to widespread disruptions in antenatal care (Chmielewska et al.,2021; Bankar et al.,2022). Many healthcare facilities reduced in-person consultations, postponed non-emergency visits, and shifted to digital health services, leaving expectant mothers with limited access to essential prenatal screenings, routine checkups, and diagnostic procedures (Goyal et al., 2022; Kassa et al., 2024). One of the major challenges during the pandemic was the suspension of regular antenatal care services, including ultrasounds, blood tests, and fetal monitoring. Research indicates that over 50% of pregnant women in India experienced difficulties in accessing routine prenatal services due to pandemic-related restrictions (Twanow et al., 2022). The fear of contracting COVID-19 at hospitals further discouraged pregnant women from seeking timely medical assistance, leading to increased risks of pregnancy-related complications such as gestational diabetes, hypertensive disorders, and fetal growth restrictions (Wei et al., 2021). These disruptions were particularly detrimental for high-risk pregnancies, where delayed care exacerbated both maternal and fetal vulnerabilities.

The pandemic also had a profound impact on maternal healthcare services in rural areas, where accessibility was already limited. Bhaumik et al.,2020 found that rural healthcare centers faced severe shortages of medical staff, essential medicines and diagnostic equipment due to supply chain disruptions. Consequently, many pregnant women in remote areas struggled to access institutional deliveries and often had to rely on traditional birth attendants, increasing the risks associated with unassisted childbirth (Farizi et al., 2023). Restrictions on public transportation made it even more challenging for women in low-income communities to reach healthcare facilities, exacerbating disparities in maternal healthcare access (Chmielewska et al., 2021). Although healthcare providers expanded telemedicine services to mitigate service gaps, digital illiteracy, poor internet connectivity and limited awareness prevented many women, particularly in rural and low-income communities, from benefitting fully from these alternatives (Farizi et al., 2023; Arora et al., 2024). Overall, the pandemic exposed critical vulnerabilities within maternal healthcare systems, highlighting the need for more resilient, equitable, and adaptable models that can sustain essential prenatal services during public-health emergencies.

3.3 The Role of Telemedicine and Digital Health in Maternal Care

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the rapid shift in healthcare delivery, with telemedicine emerging as a critical tool for ensuring continued maternal care when in-person services were restricted. Teleconsultations enabled pregnant women, especially primigravida mothers to access prenatal guidance, mental health support, and emergency consultations remotely (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare [MoHFW], 2021). A report by MoHFW (2021) indicated that teleconsultations for maternal health increased by 25% during the pandemic, allowing women to stay connected with healthcare professionals despite lockdowns and hospital service disruptions.

However, the benefits of telemedicine were unevenly distributed. Research by Arora et al.,2024 revealed that only one-third of rural women could access telemedicine services due to barriers such as limited internet connectivity, lack of smartphones, and inadequate digital literacy (Polavarapu et al., 2024). As primigravida mothers already navigating unfamiliar anxieties these barriers meant inconsistent access to essential prenatal advice and psychological support. In this context, community health workers (CHWs), including Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) and auxiliary nurse midwives (ANMs), played a pivotal role in bridging the digital gap. They assisted women in using telehealth platforms, facilitated virtual consultations, and conducted in-person follow-ups when necessary, ensuring that even those facing technological or literacy challenges could benefit from telemedicine interventions (Arora et al., 2024).

Despite these constraints, evidence suggests that telemedicine significantly improved maternal health outcomes where accessible. According to Kassa et al., (2024), women with access to telehealth reported higher satisfaction with prenatal care, as they could consult healthcare providers on nutrition, fetal development, and emotional well-being without exposure to hospital-related infection risks. Through video consultations, helplines, and mobile applications, women received psychological counseling and stress management guidance, reducing the risk of postpartum depression (Abraham et al., 2021).While telemedicine proved instrumental in maintaining maternal healthcare access, its limitations highlight the need for sustained digital health investment in expanding rural internet infrastructure, improving digital literacy among women and CHWs and integrating hybrid care models that combine telemedicine with in-person support. Such initiatives would help ensure equitable and inclusive maternal healthcare delivery in future crises.

3.4 Role of Community Workers During COVID-19

Community health workers (CHWs), including Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) in India, played an indispensable role in sustaining maternal healthcare during the pandemic, particularly for primigravida women who required more guidance and reassurance. They ensured the continuity of essential services by delivering medications, conducting home visits and offering psychosocial support to expectant mothers, particularly in rural and underserved areas (Wei et al., 2021; Nair et al., 2024). CHWs served as the primary link between pregnant women and the healthcare system when institutional access was disrupted due to lockdown and overburdened healthcare facilities (Kc et al., 2021). Their grassroots engagement helped alleviate anxieties among primigravida mothers by offering vital information about pregnancy care, COVID-19 precautions, and emotional reassurance (Salve et al., 2023).

Despite their essential contributions, CHWs encountered significant barriers that undermined their effectiveness during the pandemic. Inadequate training on infection control and insufficient access to personal protective equipment (PPE) heightened their risk of exposure, restricted them from community-based interventions (Ali et al., 2023; Sankar et al., 2024). Simultaneously, the digital divide further constrained service delivery, as many CHWs lacked smartphones, stable internet connectivity or training to use telehealth tools effectively (Arora et al., 2024). These interlinked barriers both material and technological restricted CHWs’ ability to provide consistent, safe, and responsive maternal healthcare. Integrating CHWs into digital health networks and equipping them with both protective and digital resources could strengthen healthcare resilience in future crises, enabling remote monitoring, virtual counseling, and efficient communication between pregnant women and healthcare professionals (Craighead et al., 2022; Sankar D et al., 2024).

Addressing these structural gaps requires long-term policy interventions. Governments must prioritize sustained investments in CHW training, PPE provision, and digital capacity-building to enhance both their safety and efficiency (MoHFW, 2021). Moreover, recognizing CHWs as frontline workers with fair wages and social protection would improve morale and retention, ultimately strengthening maternal health outcomes (Kurapati et al., 2024). By empowering CHWs with the necessary resources and recognition, health systems can ensure continuity and equity in maternal care during future public health emergencies.

3.5 Economic Hardships and Their Impact on Maternal Well-being

Economic instability during the pandemic severely affected the physical and psychological well-being of pregnant women, especially primigravida mothers who often require more frequent antenatal support and nutritional care (Basu et al ., 2021 ) . Job losses, reduced household income and rising healthcare costs increased financial distress, making it challenging for many expectant mothers to afford essential prenatal care, balanced nutrition, and medical support (Gurley et al., 2021). United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA, 2021) reported that economic insecurities among pregnant women led to decreased healthcare utilization, elevating the risk of adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes. In India, nearly 65% of pregnant women faced financial difficulties during COVID-19, limiting their ability to purchase supplements such as iron, folic acid, or prenatal vitamins and reducing access to routine antenatal checkups (Sharma et al., 2021). Proper maternal nutrition is crucial for fetal development, yet many women were unable to afford nutrient-rich foods, increasing risks of gestational complications such as anemia and low birth weight (Singh et al., 2023). The National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5) showed an increase in undernourishment among pregnant women during the pandemic, highlighting the direct link between financial hardship and maternal health (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare [MoHFW], 2021).

Although the Public Distribution System (PDS) was expanded to support vulnerable families, many women especially in rural and tribal areas experienced inconsistent access due to supply chain disruptions and strict lockdown measures (UNICEF, 2021). The lack of targeted economic relief for pregnant women highlighted systemic gaps in welfare provision. Strengthening social safety nets, simplifying benefit disbursement, and expanding digital financial inclusion are essential to ensuring that primigravida mothers do not bear disproportionate health burdens during future crises.

3.6 Challenges in Accessing Government Policies and Programs

Despite various government efforts to ensure maternal health support during the COVID-19 pandemic, several obstacles hindered pregnant women particularly primigravida mothers from fully benefiting from these services. The shift towards telemedicine and digital health consultations was meant to bridge healthcare gaps, but digital illiteracy and lack of technological access posed significant barriers (Goyal et al., 2022) . Singh et al., (2023) found that only 38% of rural pregnant women were aware of telehealth services, and even fewer had access to smartphones, reliable internet or digital literacy skills to utilize them effectively. Internet connectivity issues in remote regions further complicated access, leaving many women without crucial maternal health guidance and care (Craighead et al., 2022). Language barriers and the lack of culturally sensitive communication further restricted the reach of government initiatives. Many public health campaigns and digital consultations were predominantly available in English and Hindi, making them less accessible to non-Hindi-speaking populations in Tamil Nadu and other South Indian states (Krishnan et al., 2022). Pregnant women from marginalized communities also reported hesitancy in approaching institutional healthcare services due to perceived discrimination or mistreatment (Jungari et al., 2021) The fear of inadequate care, coupled with mistrust in the healthcare system, prevented many women from seeking necessary prenatal and postnatal services, increasing risks of complications and adverse maternal health outcomes.

Financial support programs such as the Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana (PMMVY) and state maternity schemes were designed to provide direct financial assistance to pregnant women. However, during the pandemic, many women reported not receiving their entitled funds due to bureaucratic hurdles, delays in processing payments and technical glitches in government portals (Mehta et al., 2023). The requirement for multiple approvals, in-person verification, and physical documentation further complicated the disbursement process, creating additional burdens for women who were unable to travel due to lock downs and fear of COVID-19 exposure (Bhaumik et al., 2020). Additionally, supply chain disruptions led to shortages of essential maternal healthcare commodities, including iron and folic acid supplements, vaccines, and even sanitary kits for postpartum care (Nguyen et al., 2021) .The lack of integration between healthcare and social welfare services exacerbated these challenges, highlighting the urgent need for streamlined, inclusive, and technologically accessible maternal health policies that ensure uninterrupted support for pregnant women, especially during public health crises.

3.7 Government Initiatives for Maternal Mental Health and Their Effectiveness

The COVID-19 pandemic underscored the urgent need for maternal mental health support in India, particularly among primigravida mothers who experienced heightened anxiety, stress, and depressive symptoms. In response, the Indian government strengthened the National Mental Health Programme (NMHP) and launched Tele-MANAS, a national tele-counseling helpline designed to deliver remote psychological assistance to vulnerable groups, including pregnant women. Although these initiatives increased the availability of mental health services, evidence indicates that their utilization remained limited due to persistent stigma, low digital literacy, and limited awareness of available intervention (Suwalska et al., 2020; Kalra et al., 2023). In Tamil Nadu, state-led community-based psychological support programs implemented through primary health centers (PHCs) and women’s self-help groups provided structured emotional support, stress-management guidance, and coping strategies for expectant mothers. Direct engagement by Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) and Anganwadi workers, through home visits and informal counseling, was particularly impactful: studies show that these grassroots efforts reduced isolation, enhanced perceived social support, and mitigated distress among pregnant women, especially in rural and marginalized communities (Navaneetham et al., 2002; Bhaumik et al., 2020; Mistry et al., 2021).

However, the overall effectiveness of these government initiatives was constrained by systemic challenges. A major limitation was the insufficient integration of maternal mental health into primary healthcare services. Many frontline workers lacked specialized training to identify or manage perinatal mental health conditions, contributing to under-diagnosis and inconsistent support (Ali et al ., 2023). Even when community workers played central roles in outreach, their efforts were hindered by inadequate PPE, increased workload, and heightened infection risk, reducing continuity of care (Bhaumik et al., 2020; Nair et al., 2024). Telemedicine intended as a key alternative during lockdowns also yielded uneven outcomes. While platforms such as Tele-MANAS expanded remote access, the actual reach was limited for low-income and rural pregnant women due to poor internet connectivity, low smartphone access, and socio-cultural barriers to seeking mental health support (Suwalska et al., 2020). These constraints reveal that although national and state initiatives introduced valuable mental health infrastructure during the pandemic, sustained improvements will require greater community-level awareness, enhanced provider training in maternal mental health, and more inclusive digital access to ensure a effective support for pregnant women during future pandemic.

4 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FUTURE PUBLIC HEALTH CRISES THROUGH GOVERNMENT INITIATIVES

The COVID-19 pandemic revealed substantial fragilities in India’s maternal-health system, reinforcing the need for stronger, crisis-responsive public-health strategies to support primigravida women. Future preparedness requires expanding digital health capacity through rural broadband enhancement, affordable mobile-data schemes and integration of maternal mental-health counselling within virtual consultation platforms, as emphasised in the Government of India’s National Digital Health Blueprint and the Guidelines for Telemedicine Services (MoHFW, 2020). Strengthening frontline health workers is equally essential: ASHAs, ANMs, and Anganwadi workers should receive structured capacity-building in perinatal mental health, reliable access to protective gear and crisis-specific financial incentives, in line with the National Health Mission’s operational guidance for maternal healthcare during emergencies (NHM,2020). To prevent disruptions in antenatal and postnatal care, states should institutionalise mobile outreach teams, emergency maternal-health units and digital tracking systems, reflecting recommendations raised in the NITI Aayog Health Systems Strengthening Report (2021).

Economic safeguards also require bolstering; maternity benefits such as PMMVY should adopt simplified enrolment and prompt disbursement mechanisms, supported by evidence that timely financial assistance mitigates maternal stress during crises (Singh et al., 2023). Integrating maternal mental health into routine care is a further priority. Finally, building resilient infrastructure including decentralised emergency response units, strong supply chains for essential medicines & supplements and strategic resource reserves is crucial for ensuring continuity of maternal services, aligning with global recommendations on pandemic-ready maternal healthcare(Kotlar et al., 2021).Collectively, these recommendations emphasise coordinated investments across digital systems, community health workforce, mental-health integration, and social protection to enhance India’s maternal-health resilience.

5 DISCUSSION & CONCLUSION

The COVID-19 pandemic unfolded as an unparalleled global crisis that disrupted healthcare systems and exacerbated psychological vulnerabilities among pregnant women, particularly primigravida mothers, who experienced pregnancy for the first time without prior coping mechanisms or established support networks. Globally, the prevalence of anxiety and depression among pregnant women rose significantly, with anxiety affecting 42% and depression 25% during the pandemic (Lebel et al., 2020). In India, where socio-economic disparities, inadequate healthcare infrastructure, and cultural constraints already challenged maternal well-being, the psychological impact was even more profound (Jungari et al., 2020). For primigravida women, fear of infection, uncertainty about delivery, and disruptions to antenatal care services heightened emotional distress. Many experienced anxiety related to the health of their unborn child, compounded by the absence of familial reassurance and limited access to healthcare facilities during lockdowns (Banerjee et al., 2023).

The psychological burden faced by primigravida mothers in India was amplified by systemic factors such as interrupted medical services, social isolation, and economic instability. Studies indicate that over half of pregnant women encountered challenges accessing prenatal checkups and essential medical services due to travel restrictions, staff shortages, and the diversion of healthcare resources to COVID-19 response efforts (Bhaumik et al., 2020). For first-time mothers, who are already susceptible to heightened pregnancy-related anxiety, these obstacles translated into significant emotional and physiological strain. Fear of visiting hospitals for routine checkups, compounded by misinformation and restricted mobility, led to deferred medical consultations and reduced adherence to prenatal care schedules (Shrivastava et al., 2021). Research further demonstrates that sustained maternal anxiety and stress during pregnancy are linked to adverse outcomes such as preterm birth and low birth weight (Goyal et al., 2022), making the plight of primigravida women during the pandemic a pressing public health concern.

Amid these challenges, the rapid deployment of telemedicine and digital health interventions offered an alternative means of continuity in maternal care. Teleconsultations for prenatal and mental health support increased by 25% nationwide, allowing many women to access professional guidance from home (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare [MoHFW], 2021). However, the benefits of telemedicine were unevenly distributed; only about one-third of rural primigravida mothers could access these services due to limited internet connectivity, poor digital literacy, and lack of awareness (Polavarapu et al., 2024). To bridge this gap, community health workers (CHWs), especially Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs), played a pivotal role by assisting expectant mothers with teleconsultations, home visits, and psychosocial counseling (Nair et al., 2024). Despite their invaluable contribution, the absence of adequate protective equipment, digital training, and fair compensation hindered their effectiveness (Ali et al., 2023). Economic hardships further compounded these mental health challenges. A significant proportion of Indian households faced job losses and income reductions, restricting access to nutritious food and healthcare essentials. Nearly 65% of pregnant women reported financial distress affecting their ability to afford prenatal vitamins and checkups (Nguyen et al., 2021). Although welfare programs like the Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana (PMMVY) and state maternity benefit schemes provided conditional cash transfers, bureaucratic hurdles and digital exclusion often delayed or denied benefits to those most in need (Mehta et al., 2023). These structural gaps underscore the necessity for simplified benefit distribution systems and crisis-sensitive maternal welfare policies.

In this context, Kerala’s Amma Manasu programme emerged as an exemplary best-practice model, demonstrating how maternal mental health can be systematically integrated into routine care (Government of Kerala, 2019). By incorporating universal screening for anxiety and depression during antenatal and postnatal visits, training frontline providers and creating stepped-care referral pathways, the programme effectively addresses the psychological dimensions of pregnancy often neglected in India’s maternal-health framework (Ganjekar et al., 2021 & The New Indian Express, 2019). Its proactive, integrated and scalable approach underscores how state-led mental-health initiatives can strengthen maternal resilience during crises. By replicating Kerala’s inclusive approach nationwide, India can build a system in order to safeguard the well-being of primigravida mothers.

References:

Abraham, A., Jithesh, A., Doraiswamy, S., Al-Khawaga, N., Mamtani, R., & Cheema, S. (2021). Telemental health use in the COVID-19 pandemic: A scoping review and evidence gap mapping. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 748069. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.748069.

Amin, R., Maqbool, M., Nazir, T., & Maqbool, M. (2022). Depression, anxiety and stress in pregnant females who tested positive for COVID-19: A cross-sectional study from South Kashmir, India. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 64(Suppl. 3), S593. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5545.341729.

Ali, A., & Kumar, S. (2023). Indian healthcare workers’ issues, challenges, and coping strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 3661. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043661.

Arora, S., Huda, R. K., Verma, S., Khetan, M., & Sangwan, R. K. (2024). Challenges, barriers, and facilitators in telemedicine implementation in India: A scoping review. Cureus, 16(8), e67388. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.67388.

Arzamani, N., Soraya, S., Hadi, F., Nooraeen, S., & Saeidi, M. (2022). The COVID-19 pandemic and mental health in pregnant women: A review article. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 949239. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.949239.

Bachani, S., Sahoo, S. M., Nagendrappa, S., Dabral, A., & Chandra, P. (2021). Anxiety and depression among women with COVID-19 infection during childbirth-Experience from a tertiary care academic center. AJOG Global Reports, 2(1), 100033. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xagr.2021.100033.

Bankar, S., & Ghosh, D. (2022). Accessing antenatal care (ANC) services during the COVID-19 first wave: Insights into decision-making in rural India. Reproductive Health, 19(1), 158. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-022-01446-2.

Basu, A., Kim, H. H., Basaldua, R., Choi, K. W., Charron, L., Kelsall, N., Hernandez-Diaz, S., Wyszynski, D. F., & Koenen, K. C. (2021). A cross-national study of factors associated with women’s perinatal mental health and wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLOS ONE, 16(4), e0249780. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0249780.

Basutkar, R. S., Sagadevan, S., Sri Hari, O., et al. (2021). A study on the assessment of impact of COVID-19 pandemic on depression: An observational study among the pregnant women. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology India, 71(Suppl. 1), 28–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13224-021-01544-4.

Bhaumik, S., Moola, S., Tyagi, J., Nambiar, D., & Kakoti, M. (2020). Community health workers for pandemic response: A rapid evidence synthesis. BMJ Global Health, 5(6), e002769. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002769.

Brooks, S. K., Webster, R. K., Smith, L. E., Woodland, L., Wessely, S., Greenberg, N., & Rubin, G. J. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet, 395(10227), 912–920. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8.

Chen, H., Guo, J., Wang, C., Luo, F., Yu, X., Zhang, W., Li, J., Zhao, D., Xu, D., Gong, Q., Liao, J., Yang, H., Hou, W., & Zhang, Y. (2020). Clinical characteristics and intrauterine vertical transmission potential of COVID-19 infection in nine pregnant women: A retrospective review of medical records. The Lancet, 395(10226), 809–815. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30360-3.

Choedon, T., Sethi, V., Killeen, S. L., Ganjekar, S., Satyanarayana, V., Ghosh, S., Jacob, C. M., McAuliffe, F. M., Hanson, M. A., & Chandra, P. (2023). Integrating nutrition and mental health screening, risk identification and management in prenatal health programs in India. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 162(3), 792–801. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.14728.

Chandra, P. S., & Nanjundaswamy, M. H. (2020). Pregnancy-specific anxiety: An under-recognized problem. World Psychiatry, 19(3), 336–337. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20781.

Chmielewska, B., Barratt, I., Townsend, R., Kalafat, E., van der Meulen, J., Gurol-Urganci, I., & Khalil, A. (2021). Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and perinatal outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Global Health, 9(6), e759–e772. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00079-6.

Coussons-Read, M. E. (2013). Effects of prenatal stress on pregnancy and human development: Mechanisms and pathways. Obstetric Medicine, 6(2), 52–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/1753495X12473751.

Craighead, C. G., Collart, C., Frankel, R., Rose, S., Misra-Hebert, A. D., Edmonds, B. T., & Farrell, R. M. (2022). Impact of telehealth on the delivery of prenatal care during the COVID-19 pandemic: Mixed methods study of the barriers and opportunities to improve health care communication in discussions about pregnancy and prenatal genetic testing. JMIR Formative Research, 6(12), e38821. https://doi.org/10.2196/38821.

Farizi, S. A., Setyowati, D., Fatmaningrum, D. A., & Azyanti, A. F. (2023). Telehealth and telemedicine prenatal care during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review with a narrative synthesis. Hospital Practice, 51(5), 241–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/21548331.2023.2284635.

Ganjekar, S., Thekkethayyil, A. V., & Chandra, P. S. (2020). Perinatal mental health around the world: Priorities for research and service development in India. BJPsych International, 17(1), 2–5. https://doi.org/10.1192/bji.2019.26.

Gopalakrishnan, L., Gutierrez, S., Francis, S., Saikia, N., & Patil, S. (2022). Barriers to maternal and reproductive health care in India due to COVID-19. Advances in Global Health, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.1525/agh.2022.1713935.

Goyal, L. D., Garg, P., Verma, M., Bhatia, R., Kumar, A., & Rana, M. (2022). Effect of restrictions imposed due to COVID-19 pandemic on the antenatal care and pregnancy outcomes: A prospective observational study from rural North India. BMJ Open, 12(e059701). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-059701.

Gundi, M., Kaikobad, R., & Sharma, S. (2025). Diversity in approaches in community-based mental health interventions in India: A narrative review and synthesis. Cambridge Prisms: Global Mental Health, 12, e89. https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2025.10046.

Gurley, N., Ebeling, E., Bennett, A., Kashondo, J. K., Ogawa, V. A., Couteau, C., ... & Shearer, J. C. (2021). National policy responses to maintain essential health services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 100(2), 168. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.21.286852.

Jagannath, R., & Chakravarthy, V. (2025). The impact of Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojna scheme on access to services among mothers and children and their improved health and nutritional outcomes. Frontiers in Nutrition, 11, 1513815. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2024.1513815.

Jungari, S. (2020). Maternal mental health in India during COVID-19. Public Health, 185, 97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2020.05.062.

Jungari, S., Sharma, B., & Wagh, D. (2021). Beyond maternal mortality: A systematic review of evidences on mistreatment and disrespect during childbirth in health facilities in India. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 22(4), 739–751. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838019881719.

Kc, A., Gurung, R., Kinney, M. V., Sunny, A. K., Moinuddin, M., Basnet, O., ... & Målqvist, M. (2020). Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic response on intrapartum care, stillbirth, and neonatal mortality outcomes in Nepal: A prospective observational study. The Lancet Global Health, 8(10), e1273–e1281. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30345-4.

Kalra, H., Tran, T., Romero, L., Sagar, R., & Fisher, J. (2023). National policies and programs for perinatal mental health in India: A systematic review. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 91, 103836. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2023.103836.

Kassa, Z. Y., Scarf, V., Turkmani, S., & Fox, D. (2024). Impact of COVID-19 on maternal health service uptake and perinatal outcomes in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(9), 1188. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21091188.

Kurapati, J., & Anitha, C. T. (2024). Community health workers’ challenges during COVID-19: An intersectionality study. Indian Journal of Community Medicine. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijcm.ijcm_53_23.

Lebel, C., MacKinnon, A., Bagshawe, M., Tomfohr-Madsen, L., & Giesbrecht, G. (2020). Elevated depression and anxiety symptoms among pregnant individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Affective Disorders, 277, 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.07.126.

Mehta, B. S., Alambusha, R., Misra, A., Mehta, N., & Madan, A. (2023). Assessment of utilisation of government programmes and services by pregnant women in India. PLOS ONE, 18(10), e0285715. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0285715.

Mistry, S. K., Harris-Roxas, B., Yadav, U. N., Shabnam, S., Rawal, L. B., & Harris, M. F. (2021). Community health workers can provide psychosocial support to the people during COVID-19 and beyond in low- and middle-income countries. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 666753. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.666753.

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW). (2020). Telemedicine Practice Guidelines (25 March 2020). Government of India. https://www.mohfw.gov.in/pdf/Telemedicine.pdf.

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW). (2021). Guidelines for maternal healthcare services during COVID-19. https://www.mohfw.gov.in.

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW). (2021). Tele MANAS: A national initiative for mental health support. https://www.mohfw.gov.in.

Nair, H. V., Sasidharan, N., Sreedevi, A., & Ramachandran, R. U. (2024). Role and function of frontline health workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in a rural health center in Kerala: A qualitative study. Cureus, 16(9), e69128. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.69128.

Nath, A., B, S., Raj, S., & Metgud, C. S. (2021). Prevalence of hypertension in pregnancy and its associated factors among women attending antenatal clinics in Bengaluru. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 10(4), 1621–1627. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_1520_20.

Navaneetham, K., & Dharmalingam, A. (2002). Utilization of maternal health care services in Southern India. Social Science & Medicine, 55(10), 1849–1869. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00313-6.

Nguyen, P. H., Kachwaha, S., Pant, A., Tran, L. M., Walia, M., Ghosh, S., ... & Avula, R. (2021). COVID-19 disrupted provision and utilization of health and nutrition services in Uttar Pradesh, India: Insights from service providers, household phone surveys, and administrative data. The Journal of Nutrition, 151(8), 2305–2316. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/nxab135.

Panolan, S., & Thomas, M. B. (2024). Prevalence and associated risk factors of postpartum depression in India: A comprehensive review. Journal of Neurosciences in Rural Practice, 15(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.25259/JNRP_584_2023.

Pankaew, K., Carpenter, D., Kerdprasong, N., Nawamawat, J., Krutchan, N., Brown, S., Shawe, J., & March-McDonald, J. (2024). The impact of COVID-19 on women’s mental health and wellbeing during pregnancy and the perinatal period: A mixed-methods systematic review. The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing. https://doi.org/10.1177/00469580241301521.

Polavarapu, M., Singh, S., Arsene, C., & Stanton, R. (2024). Inequities in adequacy of prenatal care and shifts in rural/urban differences early in the COVID-19 pandemic. Women’s Health Issues, 34(6), 597–604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2024.08.003.

Press Information Bureau, Government of India. (2021, July 30). Telemedicine regulations – Government issues Telemedicine Practice Guidelines on 25 March 2020. https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1740756.

Shrivastava, S., Rai, S., & Sivakami, M. (2021). Challenges for pregnant women seeking institutional care during the COVID-19 lockdown in India: A content analysis of online news reports. Indian Journal of Medical Ethics, VI(3), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.20529/IJME.2021.004.

Singh, T., Kaur, R., Kant, S., Mani, K., Yadav, K., & Gupta, S. K. (2023). Effect of COVID-19 pandemic on utilization of maternal healthcare services in a rural area of Haryana: A record-based comparative study. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 12(11), 2640–2644. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_99_23.

Suwalska, J., Napierała, M., Bogdański, P., Łojko, D., Wszołek, K., Suchowiak, S., & Suwalska, A. (2020). Perinatal mental health during COVID-19 pandemic: An integrative review and implications for clinical practice. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(11), 2406. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10112406.

Tripathi, S., Singh, P. K., Singh, L., Kaur Bakshi, R., Adhikari, T., Nair, S., Singh, K. J., Grover, A., & Sharma, S. (2025). Maternal and child health services during the COVID-19 pandemic in India: An interrupted time-series analysis. Frontiers in Global Women’s Health, 6, 1578259. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgwh.2025.1578259.

Twanow, J. E., McCabe, C., & Ream, M. A. (2022). The COVID-19 pandemic and pregnancy: Impact on mothers and newborns. Seminars in Pediatric Neurology, 42, 100977. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spen.2022.100977.

UNICEF. (2021). Nutrition crisis during COVID-19: Ensuring food security for pregnant women and children. https://www.unicef.org.

United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on maternal and child health. https://www.unfpa.org.

Wei, S. Q., Bilodeau-Bertrand, M., Liu, S., & Auger, N. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on pregnancy outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal, 193(16), E540–E548. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.202604.

Yan, H., Ding, Y., & Guo, W. (2020). Mental health of pregnant and postpartum women during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 617001. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.617001.

Author´s

Address:

Zuhdha Yumna Z., Research Scholar

Department of Social Work, Bharathiar University

Coimbatore, Tamilnadu– 641046

zuhdhayumna07@gmail.com

Author´s

Address:

Dr. B. Nalina, Assistant Professor

Department of Social Work, Bharathiar University

Coimbatore, Tamilnadu 641046

nalina@buc.edu.in

Author´s

Address:

Revanth R, Assistant Professor

Department of Social Work, PSGCAS

Coimbatore, Tamilnadu 641014

revanthr@psgcas.ac.in