Novel coronavirus, COVID-19: Media Perspectives and Social Workers' Perceptions on Social Development and Human Rights Challenges in Malaysia

Sarasuphadi Munusamy, University of Malaya, Jalan University

Abstract: The identification of Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) as a major rapidly spreading influenza pandemic fuelled fears of a health crisis, destabilizing national socio-economic security, as well as global security. The paper aimed to explore the COVID-19 pandemic impact on the social and economic aspect in Malaysia thematically during 1 January to 31 May 2020. This article approaches the COVID- 19 pandemic in Malaysia thematically. The papers utilized secondary information from media, news coverage and government, published sources to explore the pandemic’s consequences in Malaysia. In addition, the study incorporates perspectives from eight NGO advocates and peer supporters working in health, migration, and human rights sectors to contextualize and validate the themes emerging from news coverage. Key findings indicate that media narratives and social workers’ perceptions closely align on the major socio-developmental and human rights challenges brought by COVID-19 in Malaysia. Both perspectives demonstrated, government’s staggered yet disciplined move toward a full lockdown was medically necessary, it generated significant socio-economic disruptions, exposed human rights vulnerabilities, and intensified cross-border and migrant workers issues. Also, found that a shortage of social work human resources including limited training particularly in psychological first aid, human rights advocacy, cultural and religious sensitivity, and information and communication. These limitations underscore an urgent need to strengthen and diversify social work competencies to effectively respond to future public health emergencies.

Keywords: COVID-19 Coronavirus; Malaysia; Human rights; Socio- economic impact; culture and multiethnic; Politics in Malaysia

1 Introduction

As of May 1 2020, there have been more than 3 million confirmed coronavirus cases and a report of above 200 thousand deaths worldwide (World Health Organisation [WHO], 2020). World leaders and social scientist attributed that the world is battling with an invisible enemy; thus, the pandemic is threatening and demanding extraordinary action as preparation for the next world war (Hughes, 2024; Khrushcheva, 2020;). Malaysia is not an exception, the country has over 6779 confirmed cases with a deaths toll of about 111 as of May 14 2020, indicating it as the 4th highest among Southeast Asian countries apart from Singapore, Indonesia, and the Philippines (World Health Organisation [WHO], 2020). Malaysia encounters multiple challenges in managing Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) incorporated with geo-politics, socio-economic, and ethno-religious issues. Historically Malaysia, formally known as Malaya has witnessed terrible experiences through the Spanish Influenza in 1918, which took a death toll estimated at 35,000 to 40,000 people (Janakey Raman, 2009; Khiun, 2007; Sasidaran, 2019). The British colony documented that the larger rural agriculture and poor plantation estates were the population mainly affected, stating that this attributed to the inaccessibility of medical facilities to the local rural areas in Peninsular Malaysia. Likewise, the H1N1 influenza outbreak in 2009 reported 12307 cases with 77 deaths in Malaysia. However, managing influenzas outbreak has remained difficult on several grounds in Malaysia, particularly during early pandemic (Tee, et al., 2009).

The adverse policy implementation and mitigation of pandemic outbreak put general public in anxious and anger (Abadi, et al., 2021). The media coverage plays an important role by exchanging opinions, letting government and relevant authorities know what general public’s opinion around emerging social security, risk issues, social implementation during pandemic. In such chaotic situations, Malaysia faced multiple systemic limitations, including fragmented communication, limited preparedness, disparities in healthcare access, and social inequalities that restricted an equitable pandemic response.

Therefore, this study adopts the Chaos Theory as its theoretical framework. Chaos Theory which posits that small errors, inconsistent decisions, or gaps within a system can rapidly escalate into widespread uncertainty and unintended consequences (Calistri et al., 2024). Within this chaotic environment, vulnerable populations became even more at risk, experiencing heightened fear, mistrust, reduced healthcare-seeking behaviour, and for some devastating emotional and economic pressures that led to suicide during the COVID-19 period. Understanding Malaysia’s pandemic response through the lens of chaos theory therefore offers critical insight into how structural vulnerabilities, communication failures, and policy inconsistencies collectively shaped public experience during times of crisis. Therefore, it is not easy, given these structural limitations and the unpredictable nature of pandemic crises for health care workers and social workers in Malaysia to respond effectively to the complex and rapidly evolving needs of vulnerable communities (Mahadzir 2020; Yong, 2020).

In terms pandemic mitigation, international studies consistently demonstrate that pandemic mitigation is extremely complex, particularly because governmental responses to COVID-19 varied widely across countries (Binny, et al., 2021; Bruinen de Bruin et al., 2020). Differences were evident not only in how strict or lenient policy interventions were, but also in how quickly governments acted once initial cases were detected. The effectiveness of any intervention is further complicated by local contextual factors such as healthcare capacity, public trust, socioeconomic inequalities, and political stability which can significantly shape how communities respond to public health measures. In many cases, policy decisions were also reactive to the severity of early outbreaks, leading to uneven implementation and inconsistent outcomes (Binny, et al., 2021).

The complexity of pandemic mitigation is closely tied to the role of media as a central conduit of public communication. Many studies noted, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the media served several essential functions that directly shaped public understanding and government accountability (Razek, 2022; Sun, 2020). First, media acted as the primary channel for information sharing, especially at a time when physical distancing and movement restrictions severely limited human interaction. This made the media the main source through which communities received updates on infection trends, health guidelines, and social risks. Second, media platforms played a crucial role in communicating government policies, including lockdown announcements, financial aid measures, travel restrictions, and public health directives. Third, the media performed overseer function by monitoring government actions, reporting policy inconsistencies, and amplifying public concerns regarding human rights, social protection, and emerging vulnerabilities. However, it was also blamed for spreading rumours and false information. Studies have shown that misinformation via social and mainstream media increased fear, anxiety, and mistrust among the public, particularly affecting vulnerable groups such as migrant workers, refugees, and people with chronic illnesses (Gutenschwager, 2021; Zhao et al., 2022). During Covid-19in Malaysia, media was the major communication means, this highlights the essential role of social workers in countering misinformation, providing accurate guidance, and supporting these populations to ensure access to healthcare and uphold human rights during the pandemic. Therefore, study integrates media perspectives with social workers’ perceptions to provide a comprehensive understanding of Malaysia’s COVID-19 response. While media reporting shaped public narratives around political decisions, religious gatherings, and health measures, social workers offered frontline in-depth insights that validated, challenged, or nuanced these portrayals. By understanding these two perspectives, the study reveals the gaps between public discourse and ground realities, and highlights the human rights and social development challenges faced by marginalized communities during the pandemic.

This study provides pertinent lesson on early disease outbreak management which Malaysian government overlooked the seriousness of Covid-19 in psychosocial perspective. This study focuses on the period between 1 January and 31 May 2020 because it represents the critical early phase of the COVID-19 outbreak in Malaysia, at the time when the country was still unprepared for the scale and complexity of the pandemic. During these initial months, policy responses were rapidly evolving, information gaps were evident, and significant psychosocial and operational challenges emerged particularly in communication, public reassurance, and support for vulnerable groups. Examining this early period is therefore essential for identifying initial missteps, understanding the cultural sensitivity of local community. The dynamics of early media framing, and drawing lessons that can strengthen Malaysia’s preparedness and psychosocial response mechanisms for future public health emergencies.

2 Methodology

The study consisted of two phases: an analysis of online news sources and an examination of social workers’ perspectives. Phase one analysed local and regional online news coverage related to Malaysia over two-week period between January and May 2020. A total selected of 32 sources published between January and May 2020 were analysed, comprising 25 news media and opinion articles and 7 official documents from government authorities and international or non-profit organisations. The online news sources included The Star, The Diplomat, Berita Harian, New Straits Times, The Straits Times, Malay Mail, and Free Malaysia Today. Articles were systematically screened for relevance and thematic alignment, and only the news that containing critical analysis related to the study objectives were retained. In addition, official reports and policy documents were reviewed from key government authorities and international or non-profit institutions, including the Ministry of Health Malaysia, the Prime Minister’s Office of Malaysia, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), and the World Health Organization (WHO).

This online news collected to gain insights into the early period of pandemic as well as to explore Malaysian government’s response in managing domestic social protection. The search was conducted with the keyword “coronavirus”, “Covid-19 and Malaysia”, “social protection”, “socio-economic impact” in the Google search database. A total of 200 articles were found with the keyword search, after excluded duplicate and unrelated article with social topic were excluded, after excluded 41 articles included with 19 government related official articles sources were remained the after re-reading process, final 32 was used to identify salient issues.

In the second phase, the study incorporated the perspectives of n=8 NGO advocates and peer supporters serving in the areas of health, migration, and human rights at the local level (refer Table 1). As many studies adopted telephone or online interviews during the COVID-19 pandemic (Galvin, 2021), this study also employed tele-interviews, were conducted between May 17, 2020, and June 1, 2020. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, face-to-face interviews were not feasible because of lockdowns, mobility restrictions, and social distancing requirements. Therefore, telephone surveys were used to address the urgent need for collecting timely and policy-relevant data to understand the socioeconomic impacts of the pandemic and to inform strategies for effective responses.

The participants were selected using convenience sampling, a non-probability sampling technique. Verbal consent was obtained via telephone before the interviews, and consent forms were shared with participants electronically. The eight participants represented from NGOs that focused on human rights, healthcare, and servicing marginalized communities in Malaysia. The participants are peer supporters or advocacy members. The use of telephone interviews aligned with established qualitative trustworthiness criteria, particularly during periods when face-to-face data collection was not feasible. The researcher’s long-standing professional engagement with social workers fostered rapport, openness, and honest disclosure, which helped minimise misinformation or intentional bias. In addition, the research design was developed by the corresponding author and carried out by a trained research assistant, ensuring consistency in interview procedures and contributing to methodological rigour. These measures collectively enhance the credibility and dependability of the data.

The reviewed data for both phases were managed Using QSR NVivo 10. The findings of the common theme were analysed to establish patterns of meaning and identify emergent themes. A themes matrix was constructed to ensure all significant themes related to the aim of the integrative review were specified.

3 Result

Table 1: Participant’s background

|

|

|

N=8 |

Percentage |

||

|

Age |

Mean=39 , SD=7 |

||||

|

Gender |

Male |

5 |

62.5 |

||

|

Female |

3 |

37.5 |

|||

|

Religion |

Hindu |

2 |

50 |

||

|

Christians |

2 |

25 |

|||

|

Buddist |

1 |

12.5 |

|||

|

Muslim |

3 |

50 |

|||

|

Education |

Secondary school educate |

5 |

62.5 |

||

|

Tertiary education |

3 |

37.5 |

|||

|

Salary |

Below 1000 |

1 |

12.5 |

||

|

|

RM 1001-2000 |

3 |

37.5 |

||

|

|

RM 2001-3000 |

4 |

50 |

||

|

Type of NGO the participant working with |

Health services |

3 |

37.5 |

||

|

Serving Marginalised community |

3 |

37.5 |

|||

|

Human rights |

2 |

25 |

|||

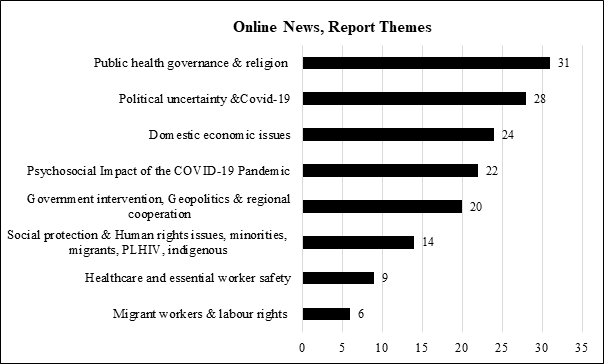

Figure 1: Themes of published online news in Malaysia on Covid-19 outbreak since 1 Jan- 31 May 2000

The analysis of the reviewed articles and data sources generated eight key themes (Refer Figure 1). These included Political Uncertainty During the Pandemic; Religion and Public Health Governance, reflecting the tensions between religious practices and health directives; Government Intervention and Regional Cooperation; Economic Impact; Healthcare and Essential Worker, Social Workers Safety , which exposed gaps in protection, training, and resources; Migrant workers & Labour Rights Challenges, focusing on job insecurity, workplace risks, and migrant labour vulnerabilities; Social Protection and Human Rights Issues; and Psychosocial Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic, encompassing widespread anxiety, stress, and mental health challenges across society. Each of these themes will be discussed in the following section, along with relevant sub-themes depicted in Figure 2.

3.1 A shift in focus from political uncertainty to COVID-19 prevention

Since China first reported novel influenza to the World Health Organisation (WHO) at the end of December 2019, ((The New Straits Times, 31 December 2019). the Malaysian government and health authorities underestimated the disaster of this disease and expected its consequences within normal parameters (The New Straits Times, 31 December 2019)). In relation to this, the influenza diseases were not subject to reporting or noticed requirements under the Prevention and Control of Infectious Diseases Act 1988 (Act 342) in Malaysia before this.

The Malaysian government was criticized for their initiated slow response against Covid-19 compared to Singapore, the Philippines, and Japan (Prashanth, 2020). The early prevention on Covid-19 being blurred due to domestic political uncertainty, such as the previous ruling coalition ‘Pakatan Harapan’, underwent internal coalition issues, meanwhile, former Prime Minister Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad was obsessed to sustaining his political power and announced that Malaysia allowed travelers from China and other international visitors, even though three visitors from Wuhan tested positive for the deadly novel coronavirus as well as being informed that China’s quarantining of the entire 11-million population as of January 25 2020 (“Wuhan Coronavirus: No plans to stop”, 2020). The globalization of people’s mobility, geographic boundaries, socio-cultural, economic relationship with China or other regions, allows the influenza to spread around to different places, including Malaysia. The first sporadic of COVID-19 cases in Malaysia were identified through three Chinese tourist women who were reported positive on January 25 2020. Then, it rose to 22 by the mid of Feb, which is believed to represent the first wave of COVID-19 cases in Malaysia (Diyana and Ahmad, 2020). In between, the resignation of Prime Minister Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad in mid of February 2020, gave room for power changes to a new coalition namely ‘Perikatan Nasional’, which is slammed as an unofficial government due to political coup (Pennington, 2019).

One of the peer supporters lamented the government’s lack of urgency in addressing the COVID-19 pandemic, stating that the leadership seemed unconcerned.

Actually, if you have notice, the government not much bother, maybe Mahathir (Prime Minister) take time to announce the ban of tourist, he took things for granted, we should band tourist quickly, see Singapore, Vietnam as already taken action, their early prevention

Here no any pre mitigation, our leaders are so much greedy on power until forget the safety of people (Political imbalance situation)

Age 34, Female, Peer Supporter of a Health NGO

3.2 Religion, public health governance, and the role of faith-based social workers

At the same time, Malaysia’s multicultural and multi-religious social structure significantly influenced public behaviour during the outbreak. Malaysia hosted the Islamic missionary movement Tablighi Jama’at gathering at Sri Petaling Mosque Complex from 27th February to 1st March. It was attended by 16,000 people, comprising 14500 Malaysians and 1,500 foreigners (Tharanya, 2020). The gathering was blamed for the fueling of the pandemic in Malaysia and even in Southeast Asia. Within this very short time period, the country has been hit by a hike of the influenza. Out of above 6000 confirmed coronavirus cases, nearly 2200 are linked to the Tabligh gathering in Malaysia (Tharanya, 2020). This gathering reported one of the largest COVID-19 clusters in Southeast Asia demonstrated how communal religious events can inadvertently accelerate viral transmission. Similar events were observed globally, such as the Shincheonji Church cluster in South Korea, which accounted for at least 60% of all national cases as of 18 March 2020 (Hernandez et al., 2020; Kang, et al., 2020). Likewise, transmission linked to pilgrimage sites in Qom, Iran spread to several Middle Eastern countries (Al-Rousan & Al-Najjar, 2020), while mass religious gatherings such as the Kumbh Mela in India created comparable public health challenges (Verma et al., 2021).

These incidents highlight a universal dilemma, whereas public health governance worldwide struggled to balance cultural and religious freedoms with urgent public health measures. Enforcement became particularly difficult due to the cultural sensitivities of diverse communities and the potential for misunderstanding or social unrest. In this context, the role of faith-based social workers is crucial. Their cultural competence, trusted community presence, and ability to communicate health risks in culturally respectful ways make them essential partners in promoting awareness, strengthening cooperation, and mitigating resistance during times of crisis. In such a situation, we can see how essential the contribution of religious or faith-based social workers is in a multi-ethnic and multi-religious country like Malaysia. Despite their significant presence and long-standing community engagement, the formal recognition and development of faith-based social workers in Malaysia remains limited. Many have been serving their communities for years providing counselling, psychosocial support, health education, and community mobilization yet the role of faith-based social workers for each ethnic groups are often overlooked in national social welfare frameworks.

Strengthening the implementation of structured support systems, capacity-building programmes, and formal collaboration mechanisms between government agencies, public health institutions, and faith-based organisations is essential. Such efforts would not only enhance community trust during public health crises, but also ensure that culturally sensitive and contextually appropriate interventions reach vulnerable groups more effectively, for example, it is crucial to have trained social workers who understand religious teachings and cultural sensitivities, as they are often better positioned to influence community behaviour especially in persuading people to avoid gatherings during a pandemic. Their messages carry moral and spiritual authority, which reaches communities in ways that common welfare social workers may not.

As a result, during a crisis, it becomes difficult to quickly locate and deploy the right people who can guide their communities effectively. Integrating faith-based social workers into broader social and health policies could significantly improve Malaysia’s resilience in managing future outbreaks and other complex social challenges. This approach also offers valuable lessons for other countries, particularly those with diverse cultural and religious landscapes, on how faith-based social workers can be strategically integrated into public health and social protection systems to strengthen community resilience during crises.

One of the peer supporters highlighted the lack of control during the initial stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly regarding ritual gatherings.

“No one controlled the situation, particularly regarding ritual gatherings. As you know, Malaysians are very active engaged in religious practices, yet there was no proper awareness given. Remember the large Muslim gathering at the Shah Alam mosque? Who should be blamed? The government failed to act early and advise people to avoid gatherings because they were afraid of losing support from the majority community, as it was seen as a religiously sensitive issue that could affect votes

Age 51, Male, Program Advocate for an NGO serving marginalized communities

“We need a social service group that represents different ethnic and religious communities. They can raise awareness, go out advise their people not to attend prayer gatherings during a pandemic, because they are trusted within their own communities and can influence behaviour more effectively. This is different from us (as general social workers) when we tell people not to go to the mosque or don’t enter temple, church. Do you think they will listen, definitely no! A trained pool or registry of faith-based social workers is essential, so that during a crisis we know exactly where to turn. (At present, such a resource does not exist)

Age 42, Male, Peer Supporter of a Health NGO

Moreover, Malaysia’s direction in preventing Covid-19 has been blurred on the preparation and steps taken to counter the influenza. There was a lack of clarity in the circulated information and communication. Nevertheless, as at mid of March 2020, the new Prime Minister Tan Sri Muhyiddin Yassin, put in place the key strategies to address the issues, such as lockdown on non-essential government and private sector services, educational institutions, including the imposition of the Movement Control Order (MCO) and continuation with Enhanced Movement Control Order (EMCO), no religious activities, mass movements and social gatherings were prohibited, restriction to travelling, border closures and strong advice given for Malaysians to stay at home.

Meanwhile, the majority of the Muslim population, who were celebrating Ramadhan, were strictly controlled in preparation for their festival, for example in buying new clothes and household items and were banned from travelling to their hometowns, reuniting with family and relatives. Despite this difficult situation, Muslims welcomed the holy month and fulfilled their religious obligation as best as they could with diligence. These restrictions were not unprecedented. A similar scenario occurred during the 1918 Spanish Flu outbreak in British colonial time in Malaya (Malaysia), which lasted from October to November 1918 (Kai, 2007). At that time, schools and educational institutions were closed, social activities were halted, and hospitals took extensive precautions such as disinfecting bed linens and patient materials. Historical accounts also describe how the public was encouraged to eat nutritious food, stay outdoors for fresh air, and how the streets were regularly watered and cleaned. Major religious and cultural events were also affected for instance, the Hindu festival of Deepavali was postponed until the influenza subsided. A

Researcher, Kai (2007) documented the situation thus:

“From October to November of 1918, school closures, empty cinemas, the deserted plantation estates and villages, corpses on streets and funerals became frequent as the influenza raged” (Kai 2007, p. 222)

This comparison shows that although COVID-19 brought significant restrictions on religious and cultural practices, Malaysia has faced similar public health challenges in the past, and communities have historically adapted with resilience.

Malaysia’s early pandemic strategies for managing a health crisis were significantly more robust than historical experiences, supported by strong government intervention and regional cooperation (Minderjeet, 2020). The government provided substantial support to the Ministry of Health (MOH), including USD 64.6 billion in stimulus packages to expand screening capacity, enhance treatment for those infected, procure ventilators and personal protective equipment (PPE), and stabilize the national economy (Prime Minister’s Office of Malaysia, 2020). Regional cooperation also played a key role, including cross-border measures, entry screenings, labour mobility restrictions, and the sharing of medical expertise, particularly from Chinese medical professionals.

3.3 Government Intervention and Regional Cooperation in Pandemic Management

The lack of medical facilities and economic aid resulted in a worse devastating effect for Malaysia at that period. However, the current strategies in combating the health crisis are more secure with government support and regional cooperation (Minderjeet, 2020). The Malaysian government had provided much-needed support to the Health Ministry (MOH) and stimulus packages approving USD 64.6 billion to increase its screening capacity, further intensify treatment for those infected, providing ventilators and personal protective equipment (PPEs), adding to the financial boost to economic stabilization (Prime Minister’s Office of Malaysia, 2020). For example, the regional cooperation comprises cross border measures, entry screenings, labour mobility restriction, and medical knowledge sharing particularly from China’s medical professional.

3.4 Economic Disruptions

The global economy has been disrupted due to the health crisis, resulting in devastating effects on Malaysia’s domestic and international economic growth. It is expected that there would be a decline in all economic sectors except the service sector, fall in household income and businesses, particularly the Small Medium Industries (SME), demand and supply chain and manufacturing sectors (Cheng, 2020). Apart from that, China’s economic shock may yield an unfavorable response effect on the Malaysian economic sectors, including tourism, because both countries maintain a favourable trading partnership (Cheng, 2020). Meanwhile, the costs to overcome COVID-19 have accelerated the nation’s economic burden, reaching a total of USD 64 billion stimulus package. The Malaysian Employers Federation (MEF) forecasts, noted that, the outbreak may increase the unemployment rate up to 13% this year compared to 3.3% in 2019. As end of February 2020, the unemployment rate rose to 3.3% or 525,500 labour force (Tan, 2020).

As part of the strategies to safeguard the economic and livelihood of Malaysia, the new government have budgeted a number of stimulation packages, including USD1 billion funds to assist Small Medium Enterprises (SMEs), small businesses, lower income individuals and workers (Aiman, 2020). For example, with the reduced interest rate to 3.5 percent for SMEs, each eligible SME can receive between RM 20,000 (USD4,500) and RM1 million (US$226,000) with a tenure of 5.5 years, on a 6-months payment moratorium. The Micro-credit scheme micro-enterprises, Credit guarantee corporation program (CGC), including BizMula-i and BizWanita-i schemes (Aiman, 2020), Working Capital Guarantee Scheme (WCGS) and Industry Restructuring Financing Guarantee Scheme (IRFGS), have been put in place to help SMEs gain access to financing from financial institutions. Additionally, there was a deferment of income tax and loan repayments, along with an exemption for companies from paying the Human Resources Development Fund (HRDF) for six months across all sectors. However, the government’s microcredit program and the six-month deferment payment moratorium are estimated to accrue unfavorable interest, potentially increasing the financial burden on lower- income loan holders in the future (Federation of Malaysian Consumers Associations FOMCA, 2020).

Furthermore, the government’s financial stimulus programme covers household earning up to RM4,000 per month, which will be given as a one-off cash pay-out of RM1600 per month (paid in two terms e.g. RM1000 in April and balance RM600 in May 2020 (Adam Aziz, 2020). In fact, various complication issues arose in getting these cash, such as the disapproval of most applications. Further, the payment covers little out of their many financial problems until June 2020 and it seems to be insufficient to cover the increased living cost (Nurafifah, 2019). In this regards, the one-off cash pay-out packages fail to cover the disbursement to the vast needy population in Malaysia. Many of them such as unemployed individuals, unemployed fresh graduates, housewives, elderly people and those suffering with disease, lamented that their applications were disapproved (Akmal Hakim, 2020). However, there have been delays due to bureaucratic processes, as one participant mentioned. This cash assistance is crucial for those in need, and participant have expressed gratitude to the government for providing relief. One individual, in particular, emphasized the struggles of the HIV community, where many people work part-time and have now lost their jobs.

I hope many people struggle, especially our community (HIV people), loss job, most of the doing part time basis, now loss it, hope government can offer financial assistance them in some way, yes sometimes problem but must apply again, sure get one. Should thank them.

Age 51, Male, Program Advocate for an NGO serving marginalized communities

3.5 Healthcare and essential worker safety challenges

In addition, The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted significant gaps in workplace protections for essential workers across various sectors, particularly healthcare, social work, logistics, and manufacturing. These workers played a crucial role in maintaining societal functions during the crisis but often faced heightened risks and inadequate safeguards, for instance healthcare workers and social workers were at the forefront of the pandemic response, long hours and burnout exposed to immense physical, emotional, and psychological challenges. The Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) Shortages encountered in many public hospitals, many healthcare facilities, especially during the initial stages of the pandemic, experienced severe shortages of PPE. Workers were forced to reuse masks, gowns, and gloves, used plastic bags and cling wrap to cover their body as PPE, this increasing their exposure to the virus (Wong & Soo, 2020). Many healthcare and social workers were not sufficiently trained to handle COVID- 19 cases, particularly in non-specialized hospitals, resulting in higher risks of infection.

What can we expect? Nothing, no proper safety dress, wear whatever we have, I see doctors and nurses working there wearing plastic covers to cover their full dress, as to protect, they said the protection stuff and dress finished, management and government unbale to provide. If we get infected with the virus, there’s nothing we can do.

Age 42, Male, Peer Supporter of a Health NGO

3.6 Labour Rights and Dilemmas

The cross-border migrant workers and emigrant workers economic opportunity was at strain. For instance, it is notable that, the Ministry of Human Resource Malaysia indicated that, there are around 40,000 Malaysians from various states working in Singapore (Yong, 2020; International Labour Office, 1997). Historically, Malaysia is represented as a ‘traditional labour source country’ for Singapore (Sparke et al. 2004). The geographical and historical ties between Malaysia and Singapore opens up the channel for migrant labour across the border since a post- independent period. However, during pandemic period both countries are struggling in maintaining labour issues due to the current COVID-19 crisis, about 1,170 Malaysians workers from Singapore were repatriated to Malaysia (Rizalman Hammim, 2020), it is estimated that, Singapore may retrench 150,000 to 200,000 workers, of which around half of them are migrant workers (Sen, 2020). This attributed as the highest retrenchments ever in Singapore’s history since independence. Malaysia’s ability to provide financial support and job opportunities for emigrant labours who returned from other countries together with 525,500 unemployed local labours is questionable (Sen, 2020).

Table 2: Government policies and actions regarding migrant workers during the COVID- 19 pandemic (2020) in Malaysia

|

Issues faced by migrant workers |

Policies or rule actions on migrant workers |

News date |

|

Job Loss / loss of income due to companies slowing down, shutting down.

Health security /emotional distress

Limited access to health care services, limited information Loss of Living Arrangements e.g. dormitory: Many workers were |

Exempted from outpatient fees. Individual suspected of having COVID-19 would receive free outpatient treatment |

January, 2020 (Andika Wahab, 2020). |

|

Announced that migrant workers would be required to pay for COVID-19 testing and treatment RM390 to RM400 (“Health DG Says Free Covid-19 Tests”,2020). |

March 2020 (“Health DG Says Free Covid-19 Tests”, 2020) |

|

|

MOH reannounced that COVID-19 treatment would be provided free of charge for foreign workers. (“Health DG Says Free Covid-19 Tests”,2020) Announced mandate testing for all migrant workers with the cost potentially borne by employers. |

12, May 2020 (Rozanna & Krishna, 2020) |

|

|

Handled undocumented migrant workers through large-scale raids and detentions. |

29, May 2020 (Amnesty International, 2020, June 21) |

Within Malaysia, the situation for migrant workers has also worsened significantly. Migrant workers, who constitute a substantial portion of Malaysia’s labor force, particularly in the construction, plantation, and domestic service sectors, faced job losses and heightened vulnerability during the pandemic. As stated in newspapers, Andika (2020) noted in her research article that Malaysia's policy on migrant workers during the COVID-19 pandemic appears to be created confusion and at times contradictory, particularly in relation to the treatment of undocumented migrants and refugees. As depicted in Table 2, initially, the government took a commendable stance by issuing a circular on January 30, 2020, that ensured migrant workers suspected of being infected with virus were exempted from outpatient fees. However, this policy shifted over time. In March 2020, the government initially announced that migrant workers would be required to pay for COVID-19 testing and treatment, estimated at RM390–RM400.This statement was later refuted by the Ministry of Health (MOH) only for Covid treatment and for testing foreign workers still need pay (“Health DG Says Free Covid-19 Tests”, 2020). Despite this, in May 2020, the government mandated that migrant workers undergo COVID-19 testing, with the cost may borne by employers, further complicating the situation (Rozanna & Krishna, 2020). The Malaysian Employers Federation (MEF) expressed disagreement with this decision, highlighting the burden it placed on employers.

Apart from the confusion caused by conflicting information on healthcare access, the situation for migrant workers worsened with large-scale raids and detentions in May 2020. This action created fear and mistrust, discouraging them from seeking COVID-19 testing and treatment. Earlier, the government had assured migrants they could safely access medical care without fear of arrest to encourage compliance with public health measures. Amnesty International Malaysia criticized the raids as “cruel and inhumane,” emphasizing that the Movement Control Order (MCO) should protect public health, not target vulnerable populations (Amnesty International (2020, June 21).

In brief, this scenario highlights the serious role of social workers in enhancing advocacy for migrant workers, particularly undocumented ones. Social workers are essential in providing accurate information, ensuring access to services, and upholding human rights and ethical principles such as dignity, respect, and social justice. They should address psychosocial needs, coordinate emergency aid, including food, healthcare, and mental health support. In addition, strengthen community networks by keeping group leaders, NGOs, and migrant workers connected even during movement restrictions.

3.7 Challenges on social protection and human rights issues

Apart from migrants, prevention, preparation and providing care and securing the minority group, who are considered to have higher health risks and vulnerable to the virus infection were the main challenging aspect for the Malaysian government, such as homeless people, refugees, asylum, indigenous people (Andika, 2020), including people with higher health risk such as HIV people, older persons, diabetic patients, hypertensive persons, those with kidney problem, heart disease, persons with disabilities, children, pregnant women as well as new born babies. There were no clear information circulation and communication from government and health authorities for these high-risk groups.

One of our members (HIV patient), high fever, he went hospital, finally they checked, got Covid (virus), (admitted), hospital staff said, not enough medical equipment has to wait for few days, almost one week he was in worse condition, fortunate he is getting better now.

Age 48, Male, peer supporter for an NGO serving HIV communities

Meanwhile Malaysian authorities were slammed for local human rights issue in handling MCO, they have arrested more than 15,000 civilians for disobeying the movement control orders (“Malaysia: Stop jailing, 2020”). The protection measure for detained people in prison, in immigration detention centres, are poorly conducted. This may also increase the risk to spread covid-19. A single mother was detained for eight days in a crowded cell of 38 people, imprisoned almost for 30 days, and slapped with RM1000 fine. The mother lamented that she was traumatized from the incident and was unable to care for and feed her children (Yiswaree, 2020). Further, the father of a deceased 17 years old boy was detained at the funeral procession for conducting a funeral, together with 26 youths for attending the funeral procession (Zack, 2020).

Ei, it is not simply to detain someone during pandemic, this is something weird beyond our usual daily routine. Remember they arrested the father who was conducting his young son’s funeral? include the father, the friends who attended funeral were arrested, and then the single mother case, she went out to buy things for the children, few days she was detained…tell me who going to feed her children. Sometimes I just don’t understand, we were not practice to get a proper information, awareness about disaster management earlier (pandemic management) because here at Malaysia we only have flood -information, and that’s not even done properly. Where got awareness on disease pandemic management. Once it happens then everybody chaos.

Age 34, Female, Peer Supporter of a Health NGO

3.8 Psychosocial Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic

Consequently, mental stress and widespread anxiety is common among the general public. Staying at home for a long period of days, self-isolation, quarantine, increased depression. In addition, loss or decline of household income, fear on health and financial problem, future direction extend stress among adult people. Several cases reported in Malaysian newspapers highlight the increase in suicide incidents during this period. For instance, by July 2020, the Malaysian Islamic Youth Force (ABIM) expressed concern over the increasing number of suicides linked to the economic and social hardships caused by the pandemic (Idrus, 2021). The organization's president highlighted that the situation had reached a critical point, with several heartbreaking incidents underscoring the severity of the crisis (Idrus, 2021; Razali et al., 2022)

One of the participants felt overwhelmed by the unimaginable stress and trauma brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic. They expressed that they never anticipated going through such a nightmare, with the loss of relatives and friends, and witnessing widespread death. The emotional strain was intensified when their wife contracted COVID-19, which nearly resulted in a devastating loss. As a social worker, they struggled to understand whom to help, feeling completely lost and unable to cope with the situation. The participant shared how fear and anxiety took over, leading to deep emotional distress.

Oh, it's unimaginable. I never thought we would go through something like this. My relatives and friends have passed away, and people are dying everywhere (of Covid 19 virus). I was traumatized when my wife contracted COVID-19, I almost lost her. As a social worker, I couldn’t even fathom who to help, feeling completely lost. I was overwhelmed, screaming in despair, fear of everything.

Age 33, Male, peer supporter of a Health NGO

Also, the frontline workers and medical personals were subject to burnout and psychological stress due to providing heavy workload, the risk of infection, the majority of them not returning home, and feeling guilty as they cannot care for their family members. There were limited mental health programmes and counselling were implemented during this period, for instance the Royal Malaysian Police Department reported a total of 631 suicide cases, include 46 migrant workers since March 2020 to May 2021 (Ganaprakasam et al., 2021). The deceased migrant workers are from Myanmar, Bangladesh, Nepal, Indonesia, India, Pakistan and Vietnam (Low, 2020).

In the educational context, the shift to e-learning introduced significant challenges, particularly for poor, rural-based students and their lower-income families, as it required access to laptops, internet broadband services, and other electronic devices. Although the Malaysian government provided free 1GB of daily data through selected telecommunications companies and distributed free smartphones to some underprivileged students, many students and teachers struggled with limited internet or Wi-Fi accessibility (Yeoh, 2020). Additionally, issues related to e-learning for disabled students and those with special needs, as well as unconducive learning environments, received far less attention. Furthermore, the cancellation of exams has contributed to increased mental stress and anxiety among students, potentially causing some to drop out of school. To prevent marginalized communities from being left behind, the Malaysian education system must explore alternative methods to deliver education effectively to disadvantaged groups.

4 Discussion

The pandemic's societal effect may be beyond the norm, including severe financial hardship, psychological distress, community alienation or stigma on victims or on their family, crime and social damage. The media played a critical role in highlighting emerging issues, such as political uncertainty, labour rights dilemmas, public health governance, and socio-economic disruptions. By systematically reporting on these events, the media not only informed the public but also created a foundation for social workers to identify pressing needs among vulnerable populations. Social workers’ perspectives largely supported the concerns raised in media reports, confirming that government measures, while medically sound, had unintended consequences on socio-economic conditions, human rights, and access to essential services. For instance, both sources highlighted the confusion surrounding policies affecting migrant workers, refugees, and other marginalized groups, including conflicting information about COVID-19 testing, treatment costs, and enforcement actions.

Social workers emphasized that these limitations contributed to fear, mistrust, and reluctance among vulnerable populations to seek medical care. In addition to healthcare avoidance, the lack of clear support systems during the pandemic intensified economic hardship and emotional distress, which were reflected in the rise of suicide cases reported during this period. These severe psychosocial consequences further reinforced the need for strong advocacy, culturally sensitive communication, and more accessible mental health support within social work. For instance, the study found that social work capacities were constrained by limited training and human resources, particularly in areas of crisis intervention, psychosocial support, human rights advocacy, and religious or cultural sensitivity. The convergence of media reports and social worker insights demonstrated the need to broaden social work competencies to include digital communication, early risk mitigation, and community engagement strategies during public health emergencies.

Beyond health and safety, Malaysia should be prepared in future on reducing social tension and reinforcing social cohesion, alongside economic mitigation efforts. It is also crucial that policies and interventions align with the healthcare system, the local socio-economic environment, and the geopolitical landscape, without conflicting with human rights or further marginalizing vulnerable groups. Besides, as noted earlier the lockdown policies allows high risk of recession or economic crisis, therefore, maximizing regional and global cooperation as well as international organization, is one of essential strategy in developing human rights and economic recoveries.

Simultaneously, religion or faith- based association play significant role to sensitize general public on health measures to prevent the spread of COVID-19. Therefore, religious and community leaders should be educated on pandemic prevention measures in order to disseminate faith -based health information for their followers. For instance, the Department of Islamic Development Malaysia (JAKIM), Malaysian Hindu Sanggam, Malaysian Chinese Muslim Association Selangor, Council of Churches of Malaysia may involve in educating general public on an importance of exemption of religious gathering and group spiritual activities, addressing the disease stigma and discrimination, supporting the lockdown measures.

Previous studies have shown that, how religious leaders have played the key role influence on the types of health-related activities being offered in their worshipers for example the Sri Lankan government cancelled all their Buddhist, Christian, Hindu, and Muslim religious festivals in public space and limiting the celebration to homes (Wijesinghe et al., 2022) and noted it led to reduce the number of new infections since earlier stage of pandemic. Similar, as early prevention measure, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), (2020) successfully trained the Islamic preachers (Imams) to disseminate the knowledge and awareness on Covid-19 during their sermons, they use their mosque megaphones and advice general population to pray from home.

In terms of information and communication government also should introduce measures to overcome the digital device in awareness and educational system during crisis and investment plan and strengthen the provision from the main central level to community level for the digitalisation processes especially for Small Medium Enterprises (SME), urban poor and rural communities.

Further in terms of social support, preparing sufficient social workers at domestic level and integrate their services with regional NGOs network is extremely important (for intake local NGOs build network with regional social workers or NGOs in Singapore, Indonesia to deal with Malaysian migrant workers wellbeing and rights) , this includes with developing training program related with health care knowledge, along with social care system to serve vulnerable group in order to manage their psychological and social needs in response of COVID-19 and future communicable disease.

In terms of theory, Chaos Theory aligns closely with this study’s findings because the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic created sudden, non-linear disruptions in social work practice, service delivery, and client wellbeing. For example, sudden The Movement Control Order (MCO updates or shifts in the classification of “essential services”, produced disproportionately large impacts on case management, client safety, and organisational functioning. This consistent with chaos theory, which emphasises how minor disturbances within complex systems can trigger significant, often unpredictable consequences.

Social workers were forced to adapt quickly, rely on improvisation, and develop new routines, reflecting the theory’s focus on flexibility and nonlinear responses. The unanticipated escalation of infections linked to a religious gathering further illustrates the “butterfly effect” within chaos theory, where a seemingly localized event generated widespread, cascading disruptions across the national public health and social care systems. This study contributes by demonstrating how applying chaos theory to the Malaysian social work context during the COVID-19 crisis provides insight into the unpredictable, rapidly shifting conditions faced by frontline practitioners, demonstrating how frontline practitioners navigated uncertainty which limitedly explored in existing pandemic-related social work literature

Finally, these mitigations only can be achieved with political stability and strong leadership at the domestic level. Hence in account of this, the COVID-19 post recovery encountered various challenges. The political instability led people loss credibility on government’s action towards prevention.

5 Conclusion

In conclusion, the counterfactual scenario of COVID-19 in Malaysia differs from that of other countries due to factors such as population size, socio-demographics, political dimensions, and economic power. The findings of this study reveal alignment between media perspectives and social workers’ perceptions regarding the social, economic, and human rights challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic in Malaysia. The spread of the pandemic was remained at a manageable level at the early period, and it is believed that Malaysia is on the path to overcoming COVID-19. However, the increasing government expenditure on the healthcare system, expand social work resources, household and business economic recovery are essential for the recovery of emerging socio-economic risks. The limited focus on building resilience based on the socio-demographics of the population and the economic environment is concerning.

Community sensitization on COVID-19 and long-term socio-economic mitigation strategies are crucial at all social levels. Social empowerment can help Malaysians better prepare to endure the effects of COVID-19 and continue to control the spread of the pandemic. Mental health support and anxiety behavior modification are essential for the entire population, particularly for victims and those grieving the loss of loved ones.

References:

Abadi, D., Arnaldo, I., & Fischer, A. (2021). Anxious and Angry: Emotional Responses to the COVID-19 Threat. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.676116.

Adam Aziz. (2020, March 27). Covid-19 stimulus package: One-off cash payout totaling RM10b for M40 and B40. The Edge Markets. https://www.theedgemarkets.com/article/covid19-stimulus-package-rm10b-oneoff-cash- payout-m40-and-b40/.

Akmal Hakim. (2020, May 12). BPN Application Denied? Here’s How you can make an appeal. The Rakyat. https://www.therakyatpost.com/news/malaysia/2020/05/12/bpn-application-denied-heres-how-you-can-make-an-appeal/.

Al-Rousan, N., & Al-Najjar, H. (2020). Is visiting Qom spread CoVID-19 epidemic in the Middle East?. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences, 24(10), 5813–5818. https://doi.org/10.26355/eurrev_202005_21376.

Amnesty International (2020, June 21). Immigration Raids on Migrant Workers During Lockdown 3.0. . https://www.amnesty.my/2021/06/04/immigration-raids-on-migrant-workers-during- lockdown-3-0/.

Andika Wahab, (2020) The outbreak of Covid-19 in Malaysia: Pushing migrant workers at the margin, Social Sciences & Humanities Open, (2)1-9.

Ayman. F.M. (2020, April 7). Malaysia issues second stimulus package to combat COVID-19: Salient features. ASEAN Briefing. https://www.aseanbriefing.com/news/malaysia-issues-second-stimulus-package-combat-covid-19-salient-features/.

Binny, R. N., Baker, M. G., Hendy, S. C., James, A., Lustig, A., Plank, M. J., ... & Steyn, N. (2021). Early intervention is the key to success in COVID-19 control. Royal Society open science, 8(11), 210488. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.210488.

Bruinen de Bruin, Y., Lequarre, A.-S., McCourt, J., Clevestig, P., Pigazzani, F., Zare Jeddi, M., Colosio, C., & Goulart, M. (2020). Initial impacts of global risk mitigation measures taken during the combatting of the COVID-19 pandemic. Safety Science, 128, 104773. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2020.104773.

Calistri, A., Francesco Roggero, P., & Palù, G. (2024). Chaos theory in the understanding of COVID-19 pandemic dynamics. Gene, 912, 148334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gene.2024.148334.

Cheng, C. (2020, March 26), COVID-19 in Malaysia: Economic impacts & fiscal responses, Institute of Strategic and International Studies. https://www.isis.org.my/2020/03/26/covid-19-in-malaysia-economic-impacts-fiscal- responses/.

Diyana. P, Razak Ahmad. (2020, April 28). Covid-19: Current situation in Malaysia, The Star Online. https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2020/03/23/covid-19-current situation-in-malaysia-updated-daily.

Federation of Malaysian Consumers Associations (FOMCA). (2020). Petition - Moratorium: BNM’s decision on Compounding Interest for all Rakyat need to be revoked!. http://www.fomca.org.my/v1/index.php/fomca-di-pentas- media/fomca-di-pentas-media-2020/846-petition-moratorium-bnm-s-decision-on- compounding-interest-for-all-rakyat-need-to-be-revoked.

Galvin, R., Burton, E., Cummins, V., O'Sullivan, M., Swan, L., Doyle, F., ... & Horgan, N. F. (2021). A qualitative study of older adults’ experiences of embedding physical activity within their home care services. Age and Ageing, 50(3), ii9-ii41.

Ganaprakasam, C., Humayra, S., Ganasegaran, K., & Arkappan, P. (2021). Escalation of Suicide Amidst The COVID-19 Pandemic in Malaysia: Progressive strategies for prevention. Malaysian Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities (MJSSH), 6 (10), 592-596.

Gutenschwager, G. (2021). Ambiguity, Misinformation and the Coronavirus. Academia Letters, 2. https://doi.org/10.20935/AL1395.

“Health DG Says Free Covid-19 Tests, Treatment for Foreigners, After PM Says Payments Required”. (2020, March 23) Code Blue. https://codeblue.galencentre.org/2020/03/health-dg-says-free-covid-19-tests-treatment-for-foreigners-after-pm-says-payments-required/.

Hernandez, M., Scarr, S., & Sharma, M. (2020). The Korean clusters. People, 119, 50. https://www.reuters.com/graphics/CHINA-HEALTH-SOUTHKOREA-CLUSTERS/0100B5G33SB/.

Hughes, D. A. (2024). “Covid-19,” psychological operations, and the war for technocracy: Volume 1. Springer Nature.

Rozanna Latiff & Krishna, N.D (2020, May 4) Migrant workers in Malaysia to undergo coronavirus tests as curbs eased. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/world/us-politics/migrant-workers-in-malaysia-to-undergo-coronavirus-tests-as-curbs-eased-idUSKBN22G0EE/.

Idrus, Pizaro. G. (2021, July 3). Suicide rising in Malaysia due to hardships amid coronavirus pandemic. Anadolu Ajansı. https://www.aa.com.tr/en/asia-pacific/suicide-rising-in-malaysia-due-to-hardships-amid-coronavirus-pandemic/2293079.

International Labour Office. (1997), Foreign construction workers in Singapore. Singapore: Industrial activities branch, Sectoral Activities Programme, https://books.google.com.my/books?id=Xz82PQAACAAJ.

Janakey Raman, M. (2009). The Malaysian Indian dilemma. Crinographicsn Sdn, Bhd, Selangor.

Kai, K. L. (2007). Terribly severe though mercifully short: the episode of the 1918 influenza in British Malaya. Modern Asian Studies, 41(2), 221-252.

Kang Y. J. (2020). Characteristics of the COVID-19 outbreak in Korea from the mass infection perspective. Journal of preventive medicine and public health, 53(3), 168–170. https://doi.org/10.3961/jpmph.20.072.

Khrushcheva, N. L. (2020, April 27). The fog of COVID-19 war propaganda. Project Syndicate. https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/trump-putin-covid19-war- rhetoric-by-nina-l-khrushcheva-2020-04.

Low C.C. (2020, December 4). Pressured during pandemic, more than 40 migrant workers end their lives. Malaysia Kini. https://malaysia.news.yahoo.com/pressured-pandemic- more-40-migrant-010000812.html.

“Malaysia: Stop jailing COVID-19 lockdown violators”. (2020, April 26). Human Rights Watch. Retrieved from https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/04/26/malaysia-stop-jailing-covid-19- lockdown-violators.

Mahadzir, D. (2020). Coronavirus, politics and economic headaches-Malaysia's defence procurement in disarray. Defence Review Asia, 14(2), 26-30.

Minderjeet, K. (2020, April 16). Asean must act, not just talk, on cooperation post-COVID- 19, say experts. Free Malaysia Today. https://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/nation/2020/04/16/asean-must-act-not- just-talk-on-cooperation-post-covid-19-say-experts/.

Nurafifah, M. S. (2019). Dissecting the rising cost of living in Malaysia. EMIR Research. https://www.emirresearch.com/dissecting-the-rising-cost-of-living-in-malaysia.

Pennington, J. (2019, January 17). Malaysia’s economy suffers as political instability continues post GE14. ASEAN Today., https://www.aseantoday.com/2019/01/malaysias-economy-suffers-as-political-instability-continues-post-ge14/.

Prashanth, P. (2020, April 7). Repatriation challenge puts Malaysia-Singapore relations amid COVID-19 into focus”. The Diplomat. https://thediplomat.com/2020/04/repatriation- challenge-puts-malaysia-singapore-relations-amid-covid-19-into-focus/.

Prime Minister’s Office of Malaysia. (2020), PM Muhyiddin shares with ASEAN Malaysia’s experience in fighting COVID-19, https://www.pmo.gov.my/2020/04/pm-muhyiddin- shares-with-asean-malaysias-experience-in-fighting-covid-19/.

Razali, S., Saw, J. A., Hashim, N. A., Raduan, N. J. N., Tukhvatullina, D., Smirnova, D., & Fountoulakis, K. N. (2022). Suicidal behaviour amid first wave of COVID-19 pandemic in Malaysia: Data from the COVID-19 mental health international (COMET-G) study. Front Psychiatry, 13, 998888. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.998888.

Razek, A., & Mustafa, M. (2022). Impact of coronavirus pandemic crisis on professional media practices. Egyptian Journal of Public Opinion Research, 21(3), 1-69.

Rizalman Hammim. (2020, April 7). 1,170 Malaysians working in Singapore have returned since April 1. New Straits Times. https://www.nst.com.my/news/nation/2020/04/582223/1170-malaysians-working- singapore-have-returned-april-1.

Sasidaran, Sellappa. (2019). Revisiting the death railway: The railway the survivors’ accounts. University of Malaya Press, Kuala Lumpur.

Sen, N. J. (2020, April 8). Covid-19 pandemic could lead to 150,000 to 200,000 retrenchments, say Maybank economists. Today Online. Retrieved from https://www.todayonline.com/singapore/covid-19-pandemic-could-lead-150000-.

Sun, Y. (2020). The Function and Significance of News Communication from the Perspective of Epidemic Prevention and Control. 6th International Conference on Social Science and Higher Education (ICSSHE 2020). 505, 581-584. 10.2991/assehr.k.201214.110.

Sparke, M., Sidaway, J. D., Bunnell, T and Grundy-Warr, C. (2004). Triangulating the borderless world: Geographies of power in the Indonesia–Malaysia–Singapore growth triangle. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 29(4),485-498.

Tan, R. (2020, April 22). Unemployment could hit 13%, says MEF. The Star. https://www.thestar.com.my/business/business-news/2020/04/22/unemployment-could-hit-13-says-mef.

Tee, K. K., Takebe, Y., & Kamarulzaman, A. (2009). Emerging and re-emerging viruses in Malaysia, 1997–2007. International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 13(3), 307-318.

Tharanya, A. (2020, March 14). 14,500 M’sians at ‘Tabligh’ gathering, 40 test positive for Covid-19”. The News Straits Times https://www.nst.com.my/news/nation/2020/03/574484/14500-msians-tabligh-gathering- 40-test-positive-covid-19.

The New Straits Times, (2019, December 31). Influenza infections still within normal parameters, says Health DG. NST online, https://www.nst.com.my/news/nation/2019/12/552217/influenza-infections-still-within- normal-parameters-says-health-dg).

United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). (2020, May 24.) Religious leaders play key role in battle against COVID-19. https://www.unicef.org/rosa/stories/religious-leaders-play-key-role-battle-against-covid- 19.

Verma, A., Verma, M., Yadav, V., Sarangi, P., & Manoj, M. (2021). An Exploratory Analysis of Activity Participation and Travel Patterns of Pilgrims in the World’s Largest Mass Religious Gathering: A Case Study of Kumbh Mela Ujjain, India. Transportation in Developing Economies, 7(2), 27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40890-021-00137-0.

Wijesinghe, M. S. D., Ariyaratne, V. S., Gunawardana, B. M. I., Rajapaksha, R. M. N. U., Weerasinghe, W. M. P. C., Gomez, P., Chandraratna, S., Suveendran, T., & Karunapema, R. P. P. (2022). Role of Religious Leaders in COVID-19 Prevention: A Community-Level Prevention Model in Sri Lanka. Journal of Religion and Health, 61(1), 687–702. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-021-01463-8.

Wong, S.W., Soo, W.J. (2020, March 23). Doctors, nurses turn to plastic bags, cling wrap amid shortage of PPE in Malaysia’s Covid-19 battle. Malaymail. https://www.malaymail.com/news/malaysia/2020/03/23/doctors-nurses-turn-to-plastic- bags-cling-wrap-amid-shortage-of-ppe-in-mala/1849203.

World Health Organisation [WHO].(2020). Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Situation Report – 115. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200514-covid-19-sitrep-115.pdf?sfvrsn=3fce8d3c_6.

Wuhan Coronavirus: No plans to stop Chinese tourists for now, says Dr M. (2020 March 25). The Star. https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2020/01/25/wuhan-coronavirus-no- plans-to-stop-chinese-tourists-for-now-says-dr-m.

Yeoh, A. (2020 April 27). MCO: As lessons move online, local teachers and students struggle with uneven Internet access. The Star Online. https://www.thestar.com.my/tech/tech- news/2020/04/27/mco-as-lessons-move-online-local-teachers-and-students-struggle- with-uneven-internet-access.

Yiswaree, P. (2020, May 7). Single mum who almost got jailed 30 days for breaking MCO cries foul, recounts traumatic ordeal. Malaymail, https://www.malaymail.com/news/malaysia/2020/05/07/single-mum-who-almost-got- jailed-30-days-for-breaking-mco-cries-foul-recoun/1864040.

Yong, S. S., & Sia, J. K.-M. (2023). COVID-19 and social wellbeing in Malaysia: A case study. Current Psychology, 42(12), 9577–9591. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02290-6.

Zack, J. (2020, April 17). MCO: 26 youths, father of deceased arrested at funeral procession in Kapar. The Star. https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2020/04/17/mco-26- youths-father-of-deceased-arrested-at-funeral-procession-in-kapar.

Zhao, Y., Zhu, S., Wan, Q., Li, T., Zou, C., Wang, H., & Deng, S. (2022). Understanding how and by whom COVID-19 misinformation is spread on social media: coding and network analyses. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 24(6), e376.

Author´s

Address:

Sarasuphadi Munusamy

Department

of Indian Studies, Faculty or Arts & Social Sciences

University of Malaya, Jalan

University

50603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

+60163045087

sarasuphadim@gmail.com.