Social Policy Interventions during COVID-19: EPFO's Role in Financial Resilience and Digital Transformation in India

Zakira Shaikh, Symbiosis College of Arts and Commerce

Abstract: The COVID-19 pandemic triggered a worldwide liquidity crisis, deeply affecting both employers and employees. To address this, India's Ministry of Labour and Employment, through the Employees’ Provident Fund Organisation (EPFO), has launched several schemes to alleviate financial hardships. This research assesses the effectiveness of EPFO's pandemic measures and their influence on financial stability, with a focus on grievance redressal, claim processing, communication, and digital adoption. Data were gathered from 34 Administrative Managers across small, medium, and large firms. A structured online questionnaire was distributed, and tests for validity and reliability ensured the robustness of the data. Chi-square analysis examined the links between digital platforms and employer satisfaction, as well as grievance resolution and claim processing times. A factor analysis of 24 items uncovered core relationships among the variables. Results showed significant links between grievance redressal and claim settlement (χ² = 18.516, df = 9, p < 0.05), employer communication and digital platforms (χ² = 11.453, df = 4, p < 0.05), and government contributions during COVID-19 and employer satisfaction (χ² = 21.587, df = 12, p < 0.05). The study also found a link between government support to employers and employees' net salaries, with a reduction in statutory rates (χ² (16) = 36.090, p < 0.05). Furthermore, Pearson correlation analysis validated relationships involving employee sustenance (.381*, p < 0.05), employer perspectives (.625**, p < 0.01), and EPFO's digital efforts (.359*, p < 0.05). Overall, these strategic actions underscore the EPFO’s pivotal role in mitigating the pandemic’s financial impact through digital advancements and enhanced operational efficiency.

Keywords: Employees’ Provident Fund; COVID-19; Financial Benefits; Employers; Employees

1 Introduction

The foundation of every economy is built on a sound and healthy labor force. Every nation strives to establish a robust labor market alongside a reliable social security system. Labor welfare, productivity, and social security are key factors in maintaining and enhancing a nation's competitiveness in the global market. A healthy, satisfied, and robust labor force is essential for the overall growth of households, society, and the economy. The welfare and social security of workers today are concerns and responsibilities shared by both employers and governments. The welfare of laborers extends beyond their own growth, development, and security to encompass the well-being of their immediate families. Regarding enforceability, the idea and practice of ‘welfare’ were never a core aspect of citizenship during post-colonial India (Jayal, 2012). Welfare encompasses a range of benefits, services, and conducive working conditions that ensure comfort and safety for employees (Baoosh & Memarzadeh, 2019). In postcolonial India, the concept of Welfarism, in its institutional and policy form, was never dependent on universal and standard human rights to social security policies, which were manifested in the centres of cosmopolitan capitalism after World War II (Nullmeier & Kaufmann, 2021; Pierson & Leimgruber, 2010). Many fields are increasingly attentive to welfare provision in an economy that isn't growing, as it presents complex fiscal, environmental, moral, and political dilemmas. These challenges impact various levels of the economy and society, with wide-ranging consequences (Corlet Walker et al., 2021). According to a report published by the Centre on Budget and Policy (2023), the priorities and benefits of social security are progressive in nature, representing a larger portion of income for low-income workers. It is often believed that developing nations lack comprehensive social safety nets, leading citizens to prioritize saving money as a precaution (Baiardi et al., 2020). In India, welfare initiatives are provided by various entities, including central and state governments, private and public sector organizations, and non-profit groups (Joseph et al., 2009). In China, the government has been increasingly investing in welfare programs and expanding coverage (Rudra, 2007). Another study concluded that welfare reforms in China are considered more productive than protective (Tillin & Duckett, 2017). The benefits of Social Security depend on the earnings on which an individual pays Social Security taxes. Every country establishes different social security schemes to promote and secure the financial well-being of its citizens.

For over seventy years, EPFO has played a crucial role in India's social security system by managing retirement plans, offering financial stability, and distributing benefits to millions of workers. However, the COVID-19 pandemic posed extraordinary challenges, causing job disruptions, falling household incomes, and increased demand for liquidity among members. To ease the financial burden on beneficiaries, the Indian government introduced several special measures through EPFO, such as reducing contribution rates, providing emergency withdrawal options, and accelerating claim processing. During the pandemic, the government recognized the importance of continuous access to social security benefits for its members and designated EPFO as one of the ‘essential services’. To meet members' urgent financial needs, EPFO created a new clause for COVID advances, allowing members to withdraw a part of their provident fund. The purpose of this study is to assess the effectiveness of EPFO during crises and whether its initiatives meet the needs of its members. Although EPFO has operated for many decades, the pandemic revealed several gaps in how it functioned before and during COVID-19, both in policy decisions and members' experiences. This paper examines this period to highlight the flexibility of India's social security systems in response to systemic shocks, thereby supporting the discussion on the importance of social protection in crisis management.

1.1 Research Objectives

The study was undertaken to examine the changing role and effectiveness of the Employees’ Provident Fund Organisation (EPFO) during COVID-19. Specifically, it aimed to identify the range of benefits offered by EPFO to both employers and employees in the periods before and during the pandemic, to assess the contribution of government initiatives in strengthening EPFO services during these phases, and to evaluate the level of satisfaction among employers and employees with the services provided by EPFO across the two timeframes.

1.2 Research Questions

RQ1. Is there an association between grievance redressal and claim settlement by EPFO?

RQ2. Is there an association between the communication made by the employer to employees about the benefits schemes of EPFO and the digital platform of EPFO satisfying the needs of employees, compared to the traditional processing of EPFO?

RQ3. Is there an association between the government helping employers by contributing to the PF during COVID-19 and the satisfaction level of employers towards EPFO?

RQ4. Is there an association between the contribution made under the PMGKY (Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Yojana) by the government to the employers and the take-home salary of employees due to a reduction in statutory rates?

RQ5. Is there any correlation between different factors extracted from the EPFO study?

2 Theoretical Background

2.1 Global Social Security Interventions

Nations frequently implement various social security programs to support individuals lacking stable income and financial security, making them vulnerable to hardship. Social security benefits aim to promote an efficient labor market and ensure a good standard of living for everyone (Nguyen et al., 2003). Among these, Social Security—particularly Old Age and Survivor Insurance—is the most significant and effective income support program ever introduced in the United States. It has been credited with reducing poverty for millions of Americans, especially the elderly (Engelhardt & Gruber, 2004). The expansion of social security tends to vary by country. In Malaysia, the retirement age under the EPF Act 1991 is set at 55 (Hassan, 2018). Several studies show that many EPFO contributors fully or partially withdraw their EPF savings once they reach 55 (Mohd Jaafar et al., 2020). An empirical study in Malaysia examined the relationship between economic growth and EPF, finding that EPF investments are statistically insignificant in the short term. The study also suggests that the savings and investments-driven growth hypothesis is more relevant as a long-term trend. The flexibility to withdraw a substantial portion of savings often results in retirees living on a small share of their funds (Schulz, 1993). Another study in Sri Lanka found that EPF members experience declining returns, leading to insufficient savings and, ultimately, financial hardship and insecurity post-retirement (Kanakaratnam & Yin, 2004). EPFOs are vital components of social security systems in many Asian countries, including India and Nepal.

These funds generally involve centralised management, individual accounts, and lump-sum withdrawals (Lindeman, 2002). In Nepal, the EPF has successfully used e-governance measures to improve efficiency and transparency (Rauniar & Pote, 2008). In contrast, EPFO India faces governance and regulatory challenges, which require reforms to enhance professionalism and implement a comprehensive, system-wide approach (Asher & Nandy, 2006). In Malaysia, the government introduced the i-Lestari and i-Sinar programs, allowing early withdrawals from the Employees’ Provident Fund (EPF), mainly used by young people and lower-income earners (Abd Ghani et al., 2023). The COVID-19 pandemic has also increased the use of Employee Assistance Programs (EAPs), emphasising the need for organizations to redefine employee well-being and expand EAP coverage (Veldsman & Van Aarde, 2021). Data shows that social protection measures adopted by governments worldwide in 2020, amounting to about 0.4% of global GDP or $5.68 trillion, greatly exceeded those during the 2007-2008 financial crisis (Gentilini et al., 2019). These estimates vary across countries. In some nations, pre-retirement withdrawals have significantly contributed to low savings among members. The ability to withdraw large sums often results in retirees living on a small portion of their funds (Dixon, 1993). The COVID-19 pandemic also caused psychological stress and anxiety, leading to social and economic decline in the labor market (Щербак et al., 2022). During the pandemic, per capita social protection and security response spending ranged from $123 in high-income countries to just $1 in low-income nations. Recent years have seen the COVID-19 pandemic severely impact household livelihoods (Tawsif et al., 2024).

2.2 Role of EPFO in India Pre and during COVID-19

Various social security reforms have become a major concern, giving policymakers the tough task of choosing from many potential policy options (van der Klaauw & Wolpin, 2008). In India, EPFO is the world's leading social security organization, with 150 million active members (Narasimhan et al., 2018). The literature shows that EPFO has traditionally operated as a bureaucratic legacy system with siloed functions and limited transparency. However, recent reforms aim to improve efficiency, accountability, and customer service by adopting ICT and process reengineering initiatives (Ravichandran & Narayanaswami, 2018). To improve EPFO services and lessen reliance on employers, EPFO introduced a Universal Account Number (UAN) in 2014 to collect members' Know Your Customer (KYC) data. The various Member IDs assigned by different organizations are now consolidated under the UAN. The goal is to link all Member Identification Numbers (Member IDs) assigned to a single member under a single Universal Account Number (as per the EPFO Annual Report 2014). In 2017, the Ministry of Electronics & Information Technology (MeitY) launched UMANG, a mobile app under the Digital India Initiative. UMANG aims to offer various Central and State government services, including registration, information search, and payments. During COVID-19, the UMANG app became an essential digital tool that enabled EPFO members to file, track, and access claims remotely. Claims submitted through UMANG increased by 180% between April and July 2020 compared to the pre-pandemic period, highlighting the platform's ability to handle mobility restrictions (EPFO Press release, 2020). Previous research indicates that during the COVID-19 pandemic, the government temporarily modified the EPF Scheme by permitting non-refundable advances of up to three months' income or 75% of the account balance. EPFO achieved this through online, contactless claim submissions. Later, during the 2021 wave, a second advance was introduced to address ongoing liquidity issues. Several annual reports from EPFO highlight a range of digital reforms and policy actions undertaken by the organization. However, there is limited empirical evidence on their effects on employers and employees. This study aims to go beyond the descriptive official reports and conduct empirical research to examine the relationship between grievance redressal and claim settlement by EPFO, as well as the link between digital communication by EPFO and employer-employee satisfaction. Additionally, the study will analyze the connection between government intervention in managing the PF and employer satisfaction during COVID-19.

3 Methods and Materials:

3.1 Research Design

The study used a quantitative, descriptive, and cross-sectional method to explore the perspectives and behaviors of employers and employees regarding the benefits provided by the EPFO before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. This research aimed to gain insights from Administrative Managers about various EPFO benefits received by employees and to evaluate the relationship between multiple factors, such as claim settlement, grievance redressal, communication from EPFO, employee satisfaction, and government reforms, as well as the satisfaction levels of both employers and employees before and during the pandemic.

3.2 Tool for Data Collection

Data was gathered through a structured online questionnaire developed with input from a Statistician and an Administrative Manager working with the EPFO, ensuring both methodological accuracy and practical relevance. A closed-ended questionnaire was created, featuring multiple-choice questions aimed at evaluating the awareness, usage, and perception of EPFO benefits among employers and employees before and during the pandemic. The final questionnaire was then distributed to various Administrative Managers across small, medium, and large firms.

3.3 Population and Sample Size

The study collected information from employers rather than individual workers to obtain accurate results. Administrative managers working in small, medium, and large businesses in a variety of industries provided the insights because they are directly in charge of overseeing EPFO-related procedures such as benefit disbursements, payroll deductions, contribution filings, and claim settlements. Their contribution to data collection, which focused on several employees rather than individual cases, offered a thorough and comparative view of EPFO utilization before and during the pandemic. Administrative managers who frequently interacted with EPFO offices' digital platforms and systems were better able to provide accurate insights regarding the effectiveness of digital initiatives, claim settlement times, and procedural efficiency because employees had limited direct access to procedural updates during the pandemic. 34 responses were gathered for analysis using a purposive sampling technique. The sample produces an approximate margin of error of ±16. 97 percent at a 95 percent confidence level and a population proportion of 60 percent. Although the small sample size is acknowledged as a methodological limitation, this approach minimized recall bias and guaranteed that the findings accurately reflected institutional practices because managers processed numerous claims during both time periods.

3.4 Data Analysis and Results

The data obtained were then systematically coded, followed by analysis using IBM SPSS 21. Descriptive statistics were used, including Simple percentages, frequency distributions, and mean values, to summarise the characteristics of respondents and the benefit utilisation patterns. To assess the hypotheses and identify correlations between the variables, inferential statistics were employed, such as Pearson's correlation coefficient and the Chi-square test.

RQ-1: Is there an association between grievance redressal and claim settlement by EPFO?

Statistical Test: Chi-square test

Hypothesis:1

H1: There is an association between grievance redressal by EPFO and claim settlement by EPFO.

Level of significance: 0.05

Table 1. Chi-square test

|

Chi-Square Tests |

|||

|

|

Value |

df |

Asymptotic Significance (2-sided) |

|

Pearson Chi-Square |

18.516 |

9 |

.030 |

|

Likelihood Ratio |

17.376 |

9 |

.043 |

|

Linear-by-Linear Association |

4.970 |

1 |

.026 |

|

N of Valid Cases |

34 |

|

|

Observation:

Chi-square=18.516, df=9, p-value<0.05

Based on the above statistics, we can conclude that the p-value is less than 0.05 and therefore, we reject the null hypothesis. Hence, the alternate hypothesis suggests that there is an association between grievance redressal by EPFO and claim settlement by EPFO.

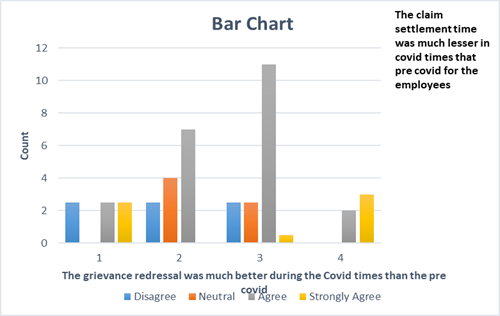

To understand this association better, we will investigate the bar chart below:

Figure 1. Association between grievance redressal and claim settlement time

From the above chart, we can say that yes, the grievance redressal was much better, and the claim settlement time was much lower, as per the responding managers.

RQ-2 Is there an association between the communication made by the employer to employees about the benefits schemes of EPFO and the digital platform of EPFO satisfying the needs of employees, compared to the traditional processing of EPFO?

Statistical Test: Chi-Square test of association

Hypothesis: 2

H2: There is an association between the communication made by the employer to employees about benefits under schemes of EPFO and the digital platform of EPFO satisfying the needs of employees compared to the traditional processing of EPFO.

Level of significance: 0.05

Table 2: Chi-square Test

|

Chi-Square Tests |

|||

|

|

Value |

df |

Asymptotic Significance (2-sided) |

|

Pearson Chi-Square |

11.543 |

4 |

.021 |

|

Likelihood Ratio |

10.959 |

4 |

.027 |

|

Linear-by-Linear Association |

8.993 |

1 |

.003 |

|

N of Valid Cases |

34 |

|

|

Observation:

χ2(4) = 11.453, p<0.05

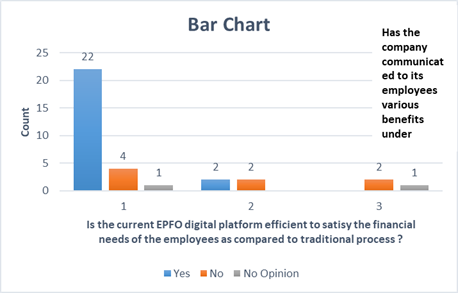

Based on the above observations, we propose rejecting the null hypothesis, thereby accepting the alternative hypothesis. This indicates that there is a significant association between the communication provided by employers to employees regarding benefits under EPFO schemes and the digital platform of EPFO, which better meets the needs of employees compared to the traditional EPFO processing methods. To understand this association, we will see the following cross-tab:

Table 3: Chi-square Test

|

|

Has the company communicated to its employees various benefits under the schemes of EPFO? |

Total |

|||

|

Yes |

No |

No opinion |

|||

|

Is the current EPFO digital platform efficient in satisfying the financial needs of the employees as compared to the traditional process? |

Yes |

22 |

4 |

1 |

27 |

|

No |

2 |

2 |

0 |

4 |

|

|

No opinion |

0 |

2 |

1 |

3 |

|

|

Total |

24 |

8 |

2 |

34 |

|

The above cross-tab suggests that if the company has communicated the various benefits under the schemes of EPFO to employees, such employees agreed that the digital platform of EPFO has efficiently satisfied their financial needs as compared to the traditional process. The same can be evident from the bar chart mentioned below:

Figure 2. Association between company communication and efficiency of the digital platform

RQ-3 Is there an association between the government helping employers by contributing to the PF during COVID-19 and the satisfaction level of employers towards EPFO?

Hypothesis: 3

H3: There is an association between the government helping employers by contributing to the PF during COVID-19 and the satisfaction level of employers towards EPFO.

Level of significance: 0.05

Table 4: Chi-Square Test

|

Chi-Square Tests |

|||

|

|

Value |

df |

Asymptotic Significance (2-sided) |

|

Pearson Chi-Square |

21.587 |

12 |

.042 |

|

Likelihood Ratio |

17.516 |

12 |

.131 |

|

Linear-by-Linear Association |

1.535 |

1 |

.215 |

|

N of Valid Cases |

34 |

|

|

Observation:

χ2(12) = 21.587, p<0.05

Based on the above observation, we suggest that we fail to reject the null hypothesis, and therefore, the alternative hypothesis is accepted. This indicates that there is an association between the government's contribution to the PF during COVID-19 and the satisfaction level of employers towards EPFO.

To understand this association, we will see the following cross-tab:

Table 5: Chi-Square Test

|

|

The government has helped employers in the tough time of COVID-19 by taking ownership of contributions to the PF, where employers were not in a position to contribute on their own. |

Total |

|||||

|

Strongly Disagree |

Disagree |

Neutral |

Agree |

Strongly Agree |

|||

|

Employers' level of satisfaction increased with the way EPFO has approached the employees' claims during COVID-19 compared to the pre-COVID-19 situation. |

Disagree |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

|

Neutral |

0 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

5 |

|

|

Agree |

0 |

0 |

2 |

18 |

1 |

21 |

|

|

Strongly Agree |

1 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

2 |

6 |

|

|

Total |

1 |

2 |

3 |

24 |

4 |

34 |

|

The above cross tab suggests that employers agree to the fact that the government has helped them during COVID-19, and hence their level of satisfaction is also there towards EPFO has also increased.

RQ-4 Is there an association between the contribution made under the PMGKY by the government to the employers and the take-home salary of employees due to a reduction in statutory rates?

Statistical Test: Chi-Square test of association

Hypothesis:4

H4: There is an association between the contribution made under the PMGKY by the government to the employers and the take-home salary of employees due to a reduction in statutory rates.

Level of significance: 0.05

Table 6: Chi-Square Test

|

Chi-Square Tests |

|||

|

|

Value |

df |

Asymptotic Significance (2-sided) |

|

Pearson Chi-Square |

36.090 |

16 |

.003 |

|

Likelihood Ratio |

29.025 |

16 |

.024 |

|

Linear-by-Linear Association |

.373 |

1 |

.541 |

|

N of Valid Cases |

34 |

|

|

Observation:

χ2(16) = 36.090, p<0.05

Based on the above observation, we suggest that we fail to reject the null hypothesis, and therefore, the alternative hypothesis is accepted. This indicates that there is an association between the contribution made by the government under the PMGKY to employers and the take-home salary of employees due to a reduction in statutory rates.

To understand this association, we will see the following cross-tab:

Table 7: Chi-Square Test

|

|

Reduction in statutory rates has helped employees to take home more salary during the COVID-19 period. |

Total |

|||||

|

Strongly Disagree |

Disagree |

Neutral |

Agree |

Strongly Agree |

|||

|

Since the government made the total contribution, employers and employees have benefited more from the PMGKY. |

Strongly Disagree |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

Disagree |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

|

|

Neutral |

0 |

0 |

2 |

5 |

1 |

8 |

|

|

Agree |

1 |

2 |

2 |

14 |

0 |

19 |

|

|

Strongly Agree |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

4 |

|

|

Total |

2 |

3 |

4 |

21 |

4 |

34 |

|

The above cross-tab suggests that employers agree to the fact that the government’s decision to reduce the statutory rates has helped employees to take home more salary.

The factor analysis has been performed on a set of 24 items; the analysis of the same is given below:

To assess the adequacy of the sample, the following statistics have been performed:

Table 8: KMO and Bartlett's Test

|

KMO and Bartlett's Test |

||

|

Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy. |

.622 |

|

|

Bartlett's Test of Sphericity |

Approx. Chi-Square |

566.778 |

|

df |

276 |

|

|

Sig. |

.000 |

|

Since Bartlett’s test of sphericity is less than 0.05, we can conclude that the sample is adequate in this case; hence, we see how much variance can be explained by the factors.

Table 9: Total Variance Captured

|

Total Variance |

||||||

|

Component |

Initial Eigenvalues |

Rotation Sums of Squared Loadings |

||||

|

Total |

% of Variance |

Cumulative % |

Total |

% of Variance |

Cumulative % |

|

|

1 |

8.348 |

34.784 |

34.784 |

4.219 |

17.580 |

17.580 |

|

2 |

3.011 |

12.545 |

47.329 |

3.201 |

13.336 |

30.915 |

|

3 |

1.871 |

7.794 |

55.123 |

2.891 |

12.047 |

42.962 |

|

4 |

1.607 |

6.696 |

61.819 |

2.563 |

10.679 |

53.641 |

|

5 |

1.473 |

6.137 |

67.956 |

2.266 |

9.442 |

63.083 |

|

6 |

1.299 |

5.411 |

73.367 |

1.981 |

8.253 |

71.336 |

|

7 |

1.159 |

4.830 |

78.197 |

1.647 |

6.861 |

78.197 |

|

8 |

.869 |

3.622 |

81.819 |

|

|

|

|

9 |

.801 |

3.340 |

85.159 |

|

|

|

|

10 |

.668 |

2.783 |

87.942 |

|

|

|

|

11 |

.571 |

2.378 |

90.320 |

|

|

|

|

12 |

.431 |

1.794 |

92.113 |

|

|

|

|

13 |

.374 |

1.557 |

93.670 |

|

|

|

|

14 |

.326 |

1.356 |

95.027 |

|

|

|

|

15 |

.288 |

1.199 |

96.225 |

|

|

|

|

16 |

.222 |

.924 |

97.149 |

|

|

|

|

17 |

.187 |

.778 |

97.927 |

|

|

|

|

18 |

.135 |

.565 |

98.492 |

|

|

|

|

19 |

.120 |

.502 |

98.994 |

|

|

|

|

20 |

.093 |

.388 |

99.382 |

|

|

|

|

21 |

.053 |

.223 |

99.604 |

|

|

|

|

22 |

.041 |

.172 |

99.777 |

|

|

|

|

23 |

.031 |

.130 |

99.906 |

|

|

|

|

24 |

.023 |

.094 |

100.000 |

|

|

|

|

Extraction Method: Principal Component Analysis. |

||||||

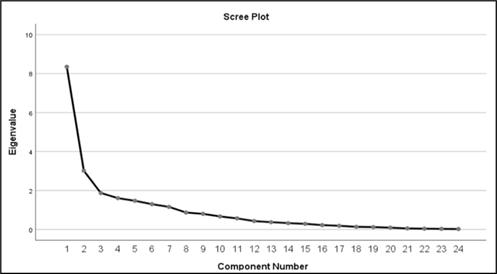

After running the PCA, we found that all the factors together explained 78% of the variation. The factor extraction is also visible through the scree plot mentioned below:

Figure 3: Screen Plot of 7 factors

Considering the above scree plot, we can see that the seven factors have been expected, but there is only one item that is getting loaded on factor 7; hence, we will only consider six factors for further research and analysis.

The loading of items on various factors is given below:

Table 10: Rotated Component Matrixa

|

Rotated Component Matrix |

|||||||

|

|

Component |

||||||

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

|

|

The EPFO claim disbursement was more convenient for employees during COVID-19 than in the pre-COVID-19 situation |

.818 |

.118 |

.207 |

.248 |

.160 |

.110 |

.153 |

|

The ECR filling was much easier during COVID-19 than in the pre-COVID-19 situation. |

.785 |

-.183 |

.101 |

.081 |

|

.103 |

.132 |

|

The EPFO has improved its services to the PF subscribers during COVID-19, as compared to the service provided pre-COVID-19 |

.722 |

.369 |

.195 |

.310 |

|

.161 |

.140 |

|

The claim settlement time was much less in COVID-19 times than in the pre-COVID-19 times for the employees |

.645 |

.211 |

-.104 |

.099 |

.214 |

.180 |

-.467 |

|

The grievance redressal was much better during the COVID-19 times than the pre-COVID-19 times. |

.626 |

.250 |

-.132 |

.207 |

.267 |

.377 |

.149 |

|

There was a rise in PF registrations considering its benefits to the beneficiaries. |

.088 |

.716 |

.254 |

.104 |

.070 |

.241 |

-.120 |

|

The employer’s contribution towards PF, pre vs during COVID-19, has affected employees’ financial security. |

|

-.675 |

-.172 |

|

.053 |

.065 |

-.163 |

|

The EPFO managed the change due to COVID-19 very well |

.474 |

.648 |

.378 |

.063 |

.192 |

-.080 |

|

|

Penal Damages for Delayed Remittance Waived for the employers to ease their financial burden was a good move from the government. |

.198 |

.611 |

-.078 |

.446 |

-.054 |

.181 |

.409 |

|

Employees' reasons for withdrawing the PF were more or less similar during the COVID-19 or pre-COVID-19 situation. |

-.090 |

.596 |

.190 |

-.073 |

.588 |

-.070 |

-.267 |

|

The PF transfer smoothly happened when new employees joined the Organisation, despite a heavy workload on the EPFO site |

.439 |

.177 |

.784 |

.157 |

|

|

|

|

Reduction in statutory rates has helped employees to take home more salary during the COVID-19 period. |

-.082 |

.217 |

.747 |

|

.138 |

-.230 |

.296 |

|

The PF policy of the government is complied with by the employers pre-COVID-19 and during the COVID-19 era. |

.378 |

.367 |

.653 |

.138 |

.084 |

.272 |

-.168 |

|

Employers' level of satisfaction increased with the way EPFO has approached the employees' claims during COVID-19 compared to the pre-COVID-19 situation. |

-.060 |

.489 |

.595 |

.356 |

|

.309 |

.120 |

|

When the PF scheme changed during COVID-19, we received adequate communication from EPFO. |

.246 |

.400 |

.407 |

.087 |

.375 |

.381 |

|

|

The EPFO scheme for waiving of contributions (employer/employees) has helped the company to retain its employees. |

.258 |

.116 |

|

.797 |

|

.061 |

.158 |

|

The Aatmanirbhar Bharat Rozgar Yojna has made a significant difference to employers and employees during COVID-19, which was not there pre-COVID-19. |

.113 |

|

.174 |

.755 |

.100 |

.231 |

|

|

Since the government made the total contribution, employers and employees have benefited more from the PMGKY. |

.182 |

.202 |

.185 |

.673 |

.088 |

-.183 |

-.389 |

|

Employees adequately understood the PF schemes pre- and during COVID-19. |

.340 |

.075 |

|

|

.883 |

.167 |

.057 |

|

The relaxation towards the contribution of the EPFO to the employers was relevant and adequate during COVID-19. |

.145 |

-.215 |

.088 |

.461 |

.671 |

|

.221 |

|

In general, the pre-COVID-19 PF benefit scheme has met employees' expectations more than during COVID-19. |

-.425 |

.133 |

.473 |

.062 |

.516 |

.309 |

-.134 |

|

During COVID-19, compared to pre-COVID-19, maximum EPFO services moved online |

.293 |

.120 |

|

.085 |

.179 |

.839 |

.171 |

|

The government has helped employers in the tough time of COVID-19 by taking ownership of contributions to the PF, where employers were not in a position to contribute on their own. |

.581 |

-.115 |

.238 |

.238 |

|

.594 |

-.177 |

|

Relaxation in Payment of Contributions was much relief to the employers when they employers are facing a liquidity crunch during COVID-19 compared to pre-COVID-19. |

.252 |

.168 |

.138 |

.090 |

.116 |

.101 |

.790 |

|

Extraction Method: Principal Component Analysis. Rotation Method: Varimax with Kaiser Normalization. |

|||||||

|

a. Rotation converged in 10 iterations. |

|||||||

Factor-1: 5, Factor-2: 4 , Factor-3: 4, Factor-4: 3, Factor-5: 3, Factor-6: 2 items have been loaded

The theme of the factors is given below:

1. Efficiency_EPFO_During_COVID-19

2. EPFO_Support_Employers_Employees

3. Perception_Employer_Towards_EPFO

4. EPFO_Employee_Sustainenance

5. Understanding_EPFO_Employees

6. EPFO_Digital_Contribution_Employer

RQ-5 Is there any correlation among various factors extracted from the EPFO study?

Statistical Test: Pearson Correlation

Hypothesis:5

H5: Correlation exists among various factors extracted from the EPFO study.

Level of Significance: 0.05

Table 11: Correlations

|

Correlations |

||||||

|

|

EPFO_Support_Employers_Employees |

Perception_Employer_Towards_EPFO |

EPFO_Employee_Sustainenance |

Understanding_EPFO_Employees |

EPFO_Digital_Contribution_Employer |

|

|

EPFO_Support_Employers_Employees |

Pearson Correlation |

1 |

.625** |

.381* |

.366* |

.254 |

|

Sig. (2-tailed) |

|

.000 |

.026 |

.033 |

.148 |

|

|

N |

34 |

34 |

34 |

34 |

34 |

|

|

Perception_Employer_Towards_EPFO |

Pearson Correlation |

.625** |

1 |

.418* |

.368* |

.315 |

|

Sig. (2-tailed) |

.000 |

|

.014 |

.032 |

.069 |

|

|

N |

34 |

34 |

34 |

34 |

34 |

|

|

EPFO_Employee_Sustainenance |

Pearson Correlation |

.381* |

.418* |

1 |

.330 |

.359* |

|

Sig. (2-tailed) |

.026 |

.014 |

|

.056 |

.037 |

|

|

N |

34 |

34 |

34 |

34 |

34 |

|

|

Understanding_EPFO_Employees |

Pearson Correlation |

.366* |

.368* |

.330 |

1 |

.346* |

|

Sig. (2-tailed) |

.033 |

.032 |

.056 |

|

.045 |

|

|

N |

34 |

34 |

34 |

34 |

34 |

|

|

EPFO_Digital_Contribution_Employer |

Pearson Correlation |

.254 |

.315 |

.359* |

.346* |

1 |

|

Sig. (2-tailed) |

.148 |

.069 |

.037 |

.045 |

|

|

|

N |

34 |

34 |

34 |

34 |

34 |

|

|

**. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). |

||||||

|

*. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed). |

||||||

EPFO_Support_Employers_Employees

· Perception_Employer_Towards_EPFO

· Understanding_EPFO_Employees

· EPFO_Employee_Sustainenance

EPFO_Digital_Contribution_Employer

· EPFO_Employee_Sustainenance

· Understanding_EPFO_Employees

The data analysis above indicates that there exists a correlation among various factors extracted from the EPFO study.

4 Discussions

The COVID-19 pandemic caused significant financial losses to individuals and businesses worldwide. During this period, the Government of India, under the Ministry of Labour and Employment, launched various relief mechanisms to help people cope with the financial crisis. One of the key initiatives by the Ministry of Labour and Employment during COVID-19 was to offer various EPF schemes and benefits to employees and employers. The analysis revealed that the result of the Chi-square test (χ² = 18.516, df = 9, p = 0.030) showed a significant correlation between grievance redressal and claim settlement by EPFO. This indicates that effective grievance management systems directly impact the speed of claim processing, which is also supported by shorter settlement times. During COVID-19, the claim settlement took place within 72 hours, with a 50 % increase in the speed of settlement when compared to pre-COVID-19. Employer communication and employee satisfaction with EPFO's digital platform are strongly linked, according to the chi-square analysis (χ² = 11.543, df = 4, p = 0.021). Employees found the digital system more effective than traditional methods when employers actively shared information about EPFO benefits. This cross-tabulation emphasises the importance of communication as a key factor in adopting digital services. During the pandemic, the Government of India under Atmanirbhar Bharat Rozgar Yojna announced a revised rate of EPF contribution, both from employee and employer, from 12 percent to 10 percent dearness allowances and basic wages. Using chi-square analysis [χ²(12) = 21.587, p < 0.05], the study found a significant relationship between employers' satisfaction with the EPFO and the government's contribution to the PF during the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, the analysis of the responses showed that the majority of employers (21 out of 34) agreed that this support raised their satisfaction levels.

In the month of March 2020, the Government also announced a special provision of withdrawal from the EPF under the PMGKY. The current analysis found a strong correlation between employees' better take-home pay and the government's PMGKY contribution. The results of the chi-square analysis (χ² (16) = 36.090, p < 0.05) supported the lower statutory rates. Moreover, component analysis identified six primary characteristics that account for71% of the variance, underscoring the critical elements influencing the benefits that PMGKY provides to employers and workers. During the pandemic, farmers and smallholders benefited greatly from India's COVID-19 social assistance package, the PMGKY. The initiative, which included direct cash transfers and in-kind assistance, helped remove credit constraints and increase investments in agricultural supplies like seeds, fertilisers, and pesticides (Varshney et al., 2021). Under the EPF schemes of 1952, the members were eligible for an amount of advance not exceeding the dearness allowances and basic wages for 3 months or up to 75 % of the amount standing to their credit in the EPF account, whichever is smaller (Financial Express, 2023). However, in the United States, Employer-sponsored health insurance remained remarkably constant, with similar premium hikes, offer rates, and employee contributions as before the pandemic (Claxton et al., 2021). The Islamic insurance industry in Indonesia showed no significant difference in gross contributions before and after the epidemic, indicating the possibility for expansion (Soleha & Hanifuddin, 2021). In Malaysia, the government permitted early withdrawals from the Employees' Provident Fund (EPF) to help members cope with economic challenges. Younger, lower-income people and those experiencing income reductions were more likely to use these withdrawal strategies (Abd Ghani et al., 2023). The analysis reveals that there is an association between grievance redressal and claim settlement by EPFO. As highlighted by (Mohd Jaafar et al.2020), the issue of early withdrawals poses a significant challenge for developing countries, where a large portion of the population struggles to meet basic livelihood needs. However, despite being a developing country, India managed the COVID-19 pandemic crisis efficiently. Notably, the Ministry of Labor and Employment, through the Employees' Provident Fund Organisation (EPFO), implemented crucial measures in April and May 2020. These included the settlement of a substantial number of claims, amounting to Rs. 36.02 lakh, and the disbursement of Rs. 11,540 crores to its members, showcasing a proactive approach to addressing financial distress during the crisis. (Financial Express, 2023a). EPFO successfully settled all claims in record time by utilising artificial intelligence in their systems and processes (ETGovernment.com, 2020). This information, combined with primary data, demonstrates a correlation between the communication provided by employers to employees regarding benefits under EPFO schemes and the EPFO digital platform, which effectively satisfies the needs of employees, compared to the traditional EPFO processing methods.

5 Conclusion

A comparative study was conducted to understand the benefits and schemes offered by EPFO pre and during COVID-19. The study also focused on understanding major strategies deployed by the Ministry of Labour and Employment to resolve the financial crises suffered by employers and employees during the pandemic. Another important aspect of research was to determine the effectiveness of digital platforms in communication, claim settlements, and other digital services to employers and employees. From the data collected, it can be inferred that EPFO played the role of a catalyst by developing a disaster preparedness model. The disaster-proof strategies were created by EPFO, which included auto-claim settlement, with no human intervention. This was possible by incorporating digitalisation in their processes and systems. EPFO formulated a multi-location work model to increase the speed of settlement and productivity of human resources by redistributing the workload of claim settlement across its 138 regional offices.

6 Limitations and Implications for Future Research

This study primarily focuses on the strategic interventions and digital transformation initiatives of the EPFO during the COVID-19 pandemic. The research is limited by a relatively small sample of 34 administrative employers, which could restrict the generalizability of the results. Nevertheless, the choice of employers as respondents was deliberate, as they serve as the main connection between employees and the EPFO/PMGKY schemes. Employers not only keep official records but also directly oversee statutory contributions and employee benefits, rendering them a reliable and suitable source of data for this study. Additionally, the study is confined to analyzing EPFO's initiatives during a specific timeframe, potentially overlooking long-term impacts and the sustainability of these measures. Future research could explore the enduring effects of these digital transformations and policy reforms on employee financial resilience and employer satisfaction. Comparative studies across different countries or regions could also shed light on the scalability and adaptability of similar interventions. Expanding the scope to include other social security Organisations could further enrich the discourse on crisis management and social protection.

ABBREVIATIONS

EPFO: Employees’ Provident Fund Organisation

PMGKY: Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Yojna

EPF: Employee Provident Fund

PF: Provident Fund

References:

Abd Ghani, M. A., Awang, H., Ab. Rashid, N. F., Yoong, T. L., Lung, T. C., Apalasamy, Y. D., Subbahi, K. F., & Mansor, N. (2023). Examining I-sinar and I-Lestari withdrawals among employees' Provident Fund (EPF) members during the COVID-19 crisis. Malaysian Journal of Consumer and Family Economics, 30(1). https://doi.org/10.60016/majcafe.v30.08.

Asher, M. G., & Nandy, A. (2006). Reforming provident and pension fund regulation in India. Journal of Financial Regulation and Compliance, 14(3), 273–284. https://doi.org/10.1108/13581980610685865.

Baiardi, D., Magnani, M., & Menegatti, M. (2019). The theory of precautionary saving: An overview of recent developments. Review of Economics of the Household, 18(2), 513–542. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-019-09460-3.

Baoosh, M., & Memarzadeh, G. H. R. (2019). Drawing model of welfare services in the Municipality of Tehran. International Journal of Human Capital in Urban Management, 4(1), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.22034/IJHCUM.2019.01.01.

Claxton, G., Rae, M., Damico, A., Young, G., Kurani, N., & Whitmore, H. (2021). Health benefits in 2021: Employer programs evolving in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Affairs, 40(12), 1961–1971. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01503.

Corlet Walker, C., Druckman, A., & Jackson, T. (2021). Welfare Systems Without Economic Growth: A review of the challenges and next steps for the field. Ecological Economics, 186, 107066. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2021.107066.

Dixon, J. (1993). National Provident Funds: The challenge of harmonizing their Social Security, social and economic objectives. Review of Policy Research, 12(1–2), 197–213. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-1338.1993.tb00517.x.

Gentilini, U., Grosh, M., Rigolini, J., & Yemtsov, R. (2019). Overview: Exploring universal basic income. Exploring Universal Basic Income: A Guide to Navigating Concepts, Evidence, and Practices, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-1458-7_ov.

Hassan, S., Othman, Z., & Din, W. (2018). Does the employees Provident Fund provide adequate retirement incomes to employees? Asian Journal of Economics, Business and Accounting, 7(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.9734/ajeba/2018/41930.

Hassan, S., Othman, Z., & Mohaideen, Z. M. (2018). The relationship between economic growth and Employee Provident Fund: An empirical evidence from Malaysia. Business and Economic Horizons, 14(2), 229–242. https://doi.org/10.15208/beh.2018.18.

Jayal, N. G. (2013). Citizenship and its discontents an Indian history. Harvard University Press. https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.4159/harvard.9780674067585/html?lang=en.

Joseph, B., Injodey, J., & Varghese, R. (2009). Labour welfare in India. Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health, 24(1-2), 221-242.

Kanakaratnam, A., & Yin, Y. P. (2004). Reforming the Sri Lankan Employee Provident Fund–A Historical and Counterfactual Simulation Perspective. https://www.gtap.agecon.purdue.edu/uploads/resources/download/1700.pdf.

Lindeman, D. C. (2002b). Provident funds in Asia: Some lessons for pension reformers. International Social Security Review, 55(4), 55–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-246x.00138.

Mohd Jaafar, N. I., Awang, H., Mansor, N., Jani, R., & Abd Rahman, N. H. (2020). Examining withdrawal in Employee Provident Fund and its impact on savings. Ageing International, 46(1), 70–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12126-020-09369-8.

Mohd Jaafar, N. I., Awang, H., Mansor, N., Jani, R., & Abd Rahman, N. H. (2020). Examining withdrawal in Employee Provident Fund and its impact on savings. Ageing International, 46(1), 70–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12126-020-09369-8.

Narasimhan, R., Vazhayil, J. P., & Narayanaswami, S. (2018). Employees’ provident fund Organisation: empowering members by Digital Transformation. Journal of Public Affairs, 18(4). https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.1844.

Nguyen, A. N., Taylor, J., & Bradley, S. (2003). Job autonomy and job satisfaction: new evidence. Lancaster University Management School, Working paper, 50. (25 pages).

Nullmeier, F., & Kaufmann, F.-X. (2021). Post-war welfare state development. The Oxford Handbook of the Welfare State, 93–111. (24 pages).

Pierson, C., & Leimgruber, M. (2010). Intellectual roots. Oxford Handbooks Online. https://academic.oup.com/edited-volume/34386.

Policy basics: Top ten facts about social security (2023) Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. (12 pages).

Rauniar, D., & Pote, R. K. (2008). Towards e-governance. Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance, 296–301. https://doi.org/10.1145/1509096.1509158.

Rudra, N. (2007). Welfare states in developing countries: Unique or universal? The Journal of Politics, 69(2), 378–396. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2508.2007.00538.x.

Schulz, j. H. (1993). Should Developing Countries Copy Chile's Pension System? Generations: journal of the American society on aging, 17(4), 70-72.

Shcherbak, V.; Ganushchak-Yefimenko, L.; Nifatova, O.; Yatsenko, V. (2022). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the intellectual labor market. International Journal of Human Capital in Urban Management, 7(1): 17-28. http://www.ijhcum.net/article_246027.html.

Soleha, A. R., & Hanifuddin, I. (2021). Perbandingan Kontribusi Bruto ASURANSI syariah sebelum Dan Sesudah pandemi covid-19. Journal of Islamic Economics and Finance Studies, 2(2), 142. https://doi.org/10.47700/jiefes.v2i2.3461.

Surabhi (2023) Financial express, The Financial Express. Available at: https://www.financialexpress.com/money/COVID-19 -19-advance-epfo-settles-claims-worth-rs-46000-cr/2993350/ (Accessed: 5 April 2023).

Surabhi (2023a) Financial express, The Financial Express. Available at: https://www.financialexpress.com/money/COVID-19 -19-advance-epfo-settles-claims-worth-rs-46000-cr/2993350/ (Accessed: 19 June 2023).

Tawsif, S., Paul, S. K., & Khan, M. S. (2024). Changing pattern of livelihood capitals of urban slum dwellers during COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Human Capital in Urban Management, 9(1). https://www.ijhcum.net/article_707648.html.

Tillin, L., & Duckett, J. (2017a). The Politics of Social Policy: Welfare Expansion in Brazil, China, India and South Africa in comparative perspective. Commonwealth & Comparative Politics, 55(3), 253–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/14662043.2017.1327925.

van der Klaauw, W., & Wolpin, K. I. (2008a). Social Security and the retirement and savings behavior of low-income households. Journal of Econometrics, 145(1–2), 21–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2008.05.004.

Varshney, D., Kumar, A., Mishra, A. K., Rashid, S., & Joshi, P. K. (2021). covid‐19, government transfer payments, and investment decisions in farming business: Evidence from Northern India. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy, 43(1), 248–269. https://doi.org/10.1002/aepp.13144.

Veldsman, D., & Van Aarde, N. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on an employee assistance programme in a multinational insurance organisation: Considerations for the future. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 47. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v47i0.1863.

www.ETGovernment.com (2020) Digital India: Epfo settles 36 lakh claims online during lockdown - et government, ETGovernment.com. Available at: https://government.economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/digital-india/digital-india-epfo-settles-36-lakh-claims-online-during-lockdown/76295266 (Accessed: 2 May 2023).

Engelhardt, G., & Gruber, J. (2004). Social Security and the Evolution of Elderly Poverty. https://doi.org/10.3386/w10466.

Ravichandran, N., & Narayanaswami, S. (2018a). Employee Provident Fund Organization (EPFO): Towards Consumer Centricity. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781529702385.

Employees' Provident Fund Organisation (2014). (publication). 62nd Annual Report- 2014-15. Retrieved from https://www.epfindia.gov.in/site_docs/Annual_Report/Annual_Report_2014-15.pdf.

Ministry of Labour & Employment (2020, August 10). EPFO Ensures Hassle Free Service Delivery through UMANG during COVID-19 Pandemic. Retrieved from https://www.epfindia.gov.in/site_docs/PDFs/EPFO_PRESS_RELEASES/PressRelease_10082020.pdf.

Author´s

Address:

Dr. Zakira Shaikh

Symbiosis College of Arts and Commerce, Pune

Senapati Bapat Road, Pune: 411004, Maharashtra, India

+918390883387

zakira.shaikh22@gmail.com