Research for better intervention: A diagnosis of loneliness in older people in times of Covid-19

Marta Mira-Aladrén, University of Zaragoza

Azucena Díez Casao, Zaragoza City Council

Pilar Sanz Martínez, Zaragoza City Council

Victoria Pérez Fernández, Zaragoza City Council

Inmaculada Leonarte Sánchez, Zaragoza City Council

Javier Martín-Peña, University of Zaragoza

Abstract: Identifying loneliness within the biopsychosocial needs of older adults is crucial for future interventions. Through a collaboration between the Municipal Social Services Centre (MSSC) Arrabal and the University of Zaragoza (Spain), an analysis of loneliness in older people has been undertaken. The objective is to explore the biopsychosocial needs and loneliness perception among elderly MSSC users, particularly following the impact of COVID-19. Methodology. This exploratory study involved 13 participants aged 65 and over, MSSC users, selected from a similar 2019 study. A semi-structured interview, designed specifically for this research, was administered using both qualitative and quantitative approaches. The script for this interview serves as a tool aimed to enhance social work practice by improving the diagnosis of situations of unwanted loneliness. Findings. Six main findings emerged: 1) COVID-19 has affected daily life. 2) Participants were satisfied with continued access to medical and social services. 3) Most did not report significant health changes, though some linked new conditions to the pandemic. 4) Social interactions with family and neighbours remained frequent, either in person or by phone. 5) Loneliness perception increased, particularly among childless and non-religious individuals. 6) Threat perception was not high, but certain activities were discontinued. Conclusions. This collaboration highlighted the importance of integrating practice with research to enhance knowledge and develop new tools, ultimately improving social work interventions with older adults. Connecting universities and social services strengthens the profession and broadens understanding.

Keywords: Social exclusion; social work; elderly; loneliness; Covid-19

1 Introduction

Loneliness and social isolation pose significant challenges for health and social services in relation to older individuals, as they impact people's well-being (e.g., NASEM, 2020; Prohaska et al., 2020). Loneliness is commonly defined as the personal perception of being alone, regardless of whether one is physically accompanied or not, while social isolation refers to the objective absence of social interactions with others (NASEM, 2020). These two conditions can be interconnected through various associated risk factors (e.g., widowhood, declining health, retirement), leading to a variety of consequences (Baarck & Kovacic, 2022).

Within Covid-19 pandemic, older adults have been identified as being at higher risk of poor outcomes if infected (WHO, 2021) experiencing greater restrictions and altering social connections (Dahlberg, 2021). The literature on loneliness/social isolation during Covid-19 have shown an increasing trend, especially during the pandemic than before the pandemic (Bhutani & Greenwald, 2021; Buecker & Horstmann, 2021; Ernst et al., 2022). In addition, some studies have noted that loneliness were higher among some general collectives of older people. For instance, findings noted that frail participants reported higher levels of loneliness compared to non-frail individuals (Joseph et al., 2023). Similarly, research conducted by Aartsen, Rothe & von Kügelgen (2023) revealed increased loneliness among older adults residing in care homes and long-term facilities, as compared to older people receiving homecare services (Wang et al., 2022).

Nevertheless, it is important to note that the effects of loneliness and social isolation on older adults' well-being and health outcomes have shown varying degrees of significance, with some studies reporting small and inconsistent effects (Beadle, Gifford & Heller, 2022; Bhutani & Greenwald, 2021; Ernst et al., 2022). Several possible explanations have been suggested in the literature. Firstly, the coping capacity, resilience, and adaptability of older adults in facing stressful situations may influence the impact of loneliness and social isolation (Fuller & Huseth-Zosel, 2021; Kadowaki & Wister, 2023; Özdemir & Çelen, 2023; Pearman et al., 2021). Secondly, the daily lives of many older adults probably did not experience significant changes compared to before the pandemic, particularly when compared to younger age groups (Lebrasseur et al., 2021). Thirdly, the heterogeneity within the older adult population, including varying levels of vulnerability and distress, such as chronic illnesses (Gruiskens et al., 2023), may contribute to the contradictory findings (Kulmala et al., 2021; Lebrasseur et al., 2021; Özdemir & Çelen, 2023).

Precisely, that heterogeneity is associated to risk factors that promote loneliness and social isolation. For instance, living alone and having a low household income predicted greater loneliness during the Covid-19 pandemic (Beadle, Gifford & Heller, 2022). However, Bu, Steptoe & Fancourt (2020) noted than risk factors during Covid-19 were similar to risk factors for loneliness before the pandemic. Thus, findings are in line with research (e.g., Dahlberg et al., 2022) from before the pandemic on risk factors of loneliness, where the most prominent risk factors were not being married/partnered and partner loss; a limited social network; a low level of social activity; poor self-perceived health; and depression/depressed mood and an increase in depressive symptoms.

Given the complexity of the issue, interventions to reduce or prevent loneliness and social isolation during Covid-19 should be targeted at those identified as high-risk individuals (Beadle, Gifford & Heller, 2022; Campaign to End Loneliness, 2021; Holt-Lunstad, 2021; Lim, Eres & Vasan, 2020; NASEM, 2020; Prohaska et al., 2020; WHO, 2021). Screening and early detection of individuals at risk of loneliness, along with understanding the underlying causes, are crucial for developing effective interventions. This preventive approach can guide the creation of suitable interventions for those most vulnerable to loneliness.

To carry out the above intervention, the role of social services and the practice of social work is crucial, in relation to the care and support of older people and to cover the psychosocial needs they may have, including the detection and prevention of loneliness. For instance, the Municipal Social Services Centres (MSSC) have access to the older people for the detection of risk factors for loneliness and psychosocial needs. And, therefore, they can focus the work and existing resources on those people who really are or could find themselves in a situation of loneliness or/and social isolation (Pinazo-Hernandis, 2020). Thus, a collaboration between the practitioners, in this case, social workers, and researchers in the academic setting is of interest to achieve evidence-based practice (Drisko & Grady, 2019). On evidence-based practice, Jones and Sherr (2014) highlight the importance of merging research and practice to achieve better care and daily practice in improving interventions.

Consequently, this paper presents an exploratory study linking social services, through the MSSC Arrabal in Zaragoza (Spain) and the University of Zaragoza. It is aimed at investigating the psychosocial needs and loneliness in times of Covid-19 of the older people of this MSSC. Thus, the work intends to be useful for MSSC specialists, helping their professional practice and their interventions on the participants of the study: the older people using social services.

1.1 Purpose of the Present Study

In this study, we proposed to contribute to generating a more optimal service for older people. The following general objective is to explore the psychosocial needs and the perception of loneliness in older people using the MSSC Arrabal, derived from the situation of Covid-19. Our specific objectives are:

1. Apply a tool (Supplementary material) adapted to the specific context of social intervention with older adults during COVID-19, which facilitates the assessment of their main psychosocial needs using the MSSC Arrabal, with a view to a possible more effective future intervention.

2. To detect the potential psychosocial needs that users may demand.

3. To analyse the users' perception of loneliness.

1.2 Social context

The MSSC Arrabal is one of the 28 MSSCs in the city of Zaragoza (Spain). It is located on the left bank of the Ebro River, near the city centre. These social services centres are responsible for general care, meaning not specialized, for the entire population of a district (a set of neighbourhoods). Specifically, this centre serves 3 neighbourhoods in Zaragoza, covering a large area with regions that vary considerably in characteristics, from the year of its creation to the demographics of the area. The neighbourhood where this study was carried out has an average age higher than the other neighbourhoods addressed by the CMSS and is considered part of the historic centre of the city, linked to its history since the 19th century.

It was also decided to initially focus on the area considered part of the historic centre of the city, integrated into the Comprehensive Historic Centre Plan (PICH) 2013-2020. This area is characterized by an aging population, old buildings under renovation, and a population historically connected to the area. All of these are considered potential risk factors. Additionally, the inclusion of this area in the PICH favoured the possibility of developing a larger number of pilot interventions to study their future implementation in the rest of the basic social services area of Arrabal, such as the expansion of preventive services (e.g., smoke detectors, energy efficiency, memory booklets, etc.) in homes and/or the promotion and participation in community meetings (talks, volunteering, specific projects, etc.) linked, among others, to the health centre, the neighbourhood association, or the CMSS itself.

2 Methodology

2.1 Approach

This study is based on a previous collaboration, conducted in 2019 with the MSSC Arrabal, in which a pilot instrument was developed to assess various social needs and the perception of loneliness among elderly individuals using the MSSC. Building on that first study, this second study was proposed in 2021 to assess the impact of Covid-19 on those same participants, including some new items in the instrument used in 2019. According to this context, this is a study oriented to an exploratory and descriptive sequential mixed method (Creswell & Creswell, 2018; Creswell & Plano, 2018) in which the research begins first with a qualitative research phase, and the information is used to build a second quantitative phase. Thus, in this study data of participants were collected through a semi-structured first model of interview. The interview collected data through qualitative and quantitative items and was then transformed into a more quantitative approach, through the construction of a database, in which the interview variables were coded. The construction of databases can foster the systematic and regular recording of information from MSSC users, fostering more efficient medium- and long-term decision making. This methodology can contribute to the future creation of an assessment instrument useful for the MSSC and their users, and to obtain richer and more complete data and future modelling.

2.2 Participants

Participants were older people over 65 years old (both men and women) users of MSSC from Arrabal neighbourhood, in Zaragoza (Spain). These users were beneficiaries of the Home Help Service (HHS) and/or Telecare Service (TC). The sample (N = 13) was selected from the HHS list of users, and it was completed with some other users randomly selected from the TC list, all from the MSSC archives. Furthermore, considering that we had data from 2019 on 33 older adults who use the MSCC, we added as an inclusion criterion that these participants had been previously interviewed in 2019. In this way, we could compare the data collected in this study with that from 2019, allowing us to assess the impact of COVID-19 on some aspects related to the perception of loneliness. The exclusion criteria were several cognitive impairments that prevented the understanding and development of the interview. Finally, 13 of the above participants could be selected in 2021, allowing some comparisons to be made between 2019 and 2021.

Participants were interviewed in February and March 2021, once their consent for the interview was obtained from MSSC social workers. Three interviews were conducted by telephone and 10 face-to-face. Average duration of the interviews was 25 minutes.

The characteristics of the participants (see Table 1) were mainly female, widowed, living alone, and users of HHS and TC.

Table 1. Sample characteristics

|

Variables

f |

|

|

Sex |

|

|

Man |

3 |

|

Woman |

10 |

|

Marital status |

|

|

Single |

2 |

|

Widowed |

9 |

|

Divorced |

2 |

|

Level of studies |

|

|

No education |

1 |

|

Basic education |

11 |

|

Secondary education |

1 |

|

Sons/Daughters |

|

|

Yes |

9 |

|

No |

4 |

|

Live alone |

|

|

Yes |

13 |

|

No |

0 |

|

Age |

Years |

|

Average |

84,2 |

|

Median |

86 |

|

Standard Deviation |

7,87 |

|

Minimum |

68 |

|

Maximum |

92 |

2.3 Data collection

To assess the potential needs of the participants, a semi-structured first interview model was designed, looking for a relatively easy and quick to use instrument, adapted for older people and useful for social workers. The interview was classified into six dimensions: 1) sociodemographic by participants; 2) Daily life; 3) Access to services; 4) Health; 5) Social-relational; 6) Perception of risk, and coping. The interview questions were open-ended, dichotomous and also Likert-type scaled. These items were based in the needs of the MSSC, previous research (e.g., Van Tilburg et al., 2021) about loneliness and health during Covid-19, and items on stress and depression collected from strategies and measures on social and behavioural dimensions were also used (Adler & Stead, 2015). Specifically, to assess the perception of loneliness, the De Jong scale was used in its short version adapted to Spanish (Buz & Prieto, 2013; Tomás et al., 2017). The reasons for selecting this questionnaire over other instruments for assessing loneliness were: 1) the reduced number of items, with questions that are reasonably easy for the elderly to understand; 2) the more intuitive way of answering, with only 3 options; 3) its adaptation to Spanish language; 4) its recommendation as a standardised instrument (NASEM, 2020).

2.4

Procedure

The study was carried out within the framework of the professional practice of social workers, at the MSSC Arrabal in the city of Zaragoza (Spain), in collaboration with the University of Zaragoza. The director of the MSSC and three social workers conducted the interviews. The university researchers participated in the design, analysis, and supervision of the study. As Jones and Sherr (2014) pointed out, academics interactions with practitioners may provide information to act toward addressing social problems within social work practice. In this sense, this study is framed within the public policies and institutional recommendations on the care and protection of the elderly.

All the participants received information about the study, about the commitment to treat the information according to the ethical principles of research and the Helsinki Declaration, and were instructed to accept an informed consent (verbal or written). They were informed about the confidentiality of the collected data, with no access by third parties, and not to use them for purposes other than those described in the project. Participants and family members were given feedback on the data collected in 2019, through a leaflet and a video: https://youtu.be/k3x-HeavZK0 inviting them to participate in a new interview.

2.5 Data analysis

The interviews were transcribed (Mayring, 2014) and the variables comprising the interviews were coded in a database created in PASW-20 software. Quantitative variables were analysed through a descriptive analysis. Qualitative variables were analysed through a simple inductive content analysis, where the main codes are extracted from the open-ended responses of participants. The codes used were: Need for communication and social relationships; satisfaction/dissatisfaction with institutions; use of coping strategies; aging and health problems; and satisfactory family relationships. The unit of analysis was the complete response to each interview question. The interview transcripts were anonymised by the interviewers, assigning a random number to each participant, which replaced any personal reference that could identify them throughout the text. According to the aims of the study, the demographics data (sex, age, marital status, level studies, etc.) of each of the participants were also analysed in detail, providing to the social workers key information for a better intervention.

3 Results

Within the results, and with respect to the first objective of this study, a database has been created, comprising the variables used in the interview. The model of interview is a first model of instrument focused on the needs considered by social workers in the MSSC. Thus, the results obtained from the interviews are shown below, classified according to the six dimensions mentioned above (sociodemographic by participants, daily life, access to services, health perception, social-relational, and perception of risk and coping).

3.1 Sociodemographic by participants

In detail, Table 2 shows the sociodemographic data of each participant, which may be useful for social service providers in order to identify the needs of each user. This, in turn, promotes individual and person-centred assistance, according to the principles of social work.

Table 2. Sample characteristics by participant

|

Participant |

Age |

Sex |

Marital status |

Children |

Education Level |

Practice of religious

belief |

|

1 |

86 |

Woman |

Widowed |

Yes |

Basic |

Yes |

|

3 |

92 |

Man |

Widowed |

Yes |

Basic |

No |

|

4 |

82 |

Woman |

Widowed |

No |

Basic |

NS-NC |

|

5 |

92 |

Woman |

Widowed |

Yes |

Basic |

Yes |

|

6 |

83 |

Woman |

Single |

No |

Basic |

Yes |

|

8 |

89 |

Woman |

Widowed |

Yes |

Basic |

Yes |

|

12 |

91 |

Woman |

Divorced |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

|

18 |

91 |

Man |

Widowed |

Yes |

Basic |

Yes |

|

20 |

73 |

Man |

Single |

No |

Basic |

No |

|

22 |

89 |

Woman |

Widowed |

Yes |

Basic |

Yes |

|

26 |

75 |

Woman |

Divorced |

Yes |

Basic |

Yes |

|

29 |

68 |

Woman |

Widowed |

No |

Secondary |

No |

|

33 |

84 |

Woman |

Widowed |

Yes |

Basic |

Yes |

Note. All participants live alone. The age corresponds to the year 2021.

3.2 Daily life

In relation to aspects linked to daily life, regarding the quantitative results, the participants indicated whether the Covid-19 situation affected their daily life. When asked what they believed had worsened in their daily life due to the Covid-19, participants pointed out some aspects: feeling low (Participants 1, 6, 8, 12, 20), impact on restrictions on daily life, such as not seeing the family or not going out much (Participants 1, 4, 8, 12, 22, 33). Although some participants (N = 3) indicated that there have been no relevant changes in their daily life, they did not feel that their daily life was affected. In terms of affectation, going out less was one of the most frequently mentioned aspects.

In Table 3, the complementary qualitative results provided by the participants can be seen:

Table 3. COVID-19 situation and day-to-day experiences

|

Participant |

What do you think has

become (more) worse with the COVID-19 situation on a day-to-day basis? |

What has changed with

COVID-19 in your day-to-day life? |

|

1 |

I notice that I am

feeling low. I think of my children and grandchildren. |

I am still doing the

same as before. |

|

3 |

--- |

He does not leave the

house |

|

4 |

I am still the same,

little comes out. |

--- |

|

5 |

Nothing |

Yes it has changed |

|

6 |

I go out less and when

I do, I go out in fear of contagion |

A niece was supposed

to visit me for a few days, but was unable to go |

|

8 |

I am sadder, even

though my children are "on top" of my. |

--- |

|

12 |

I am more nervous

because of what we are going through, and I can't visit my children or my

granddaughter, who used to go to lunch with me on some days. |

--- |

|

18 |

I think I am better. |

Nothing, it is the

same. |

|

20 |

Yes, I am afraid |

Coexisting with

people, I think we are distancing ourselves. |

|

22 |

Yes, it can't get any

better being cooped up, when the good weather comes I plan to go to the

village to get out more. |

I can't go out that

much |

|

26 |

Yes, it has worsened |

I hardly ever leaves

the house and is less self-sufficient. |

|

29 |

Yes, because I had a

stroke, then I broke my knee and has more difficulty walking. |

Nothing |

|

33 |

Not being able to

communicate (see) with the family. |

Would like to be able

to go out more. |

3.3 Access to services

Regarding access to services in the Covid-19 the majority of users were able to remain in contact with health services by phone, if they needed them (both doctors and nurses). When asked whether they felt they received the response they needed from health services, 10 out of 13 answered in the affirmative.

The 13 users said they were happy with the Home Help Service, 12 said they were happy with the person who assists them at home, and one said she was not (Participant 26). As to whether they preferred not to have the assistant come to the house for fear of contracting Covid-19, two people answered yes, compared to 11 who did not. Two people had food delivered to their homes, and they were happy with this service.

In respect of how their needs in activities of daily living (help to have a shower, cook, shopping, go to the doctor, etc.) have changed with Covid-19, seven participants indicated that there were no changes. With reference to whether they felt that they needed help with housework, and if they asked for this help, five participants indicated that they did not need this help at the moment. Other participants indicated that when they needed some additional support, they received it.

On the needs that they felt were not met, Participant 8 indicated that she "thinks she needs more company", while most of the rest tended to indicate that they did not feel they had an unmet need. When we asked them if they would like to be offered any additional services, such as a home library or similar, a large number of participants said no. Participant 33 said that the library might be a good idea. The majority of users (9), did not use technology to communicate and interact with their friends. Six participants explicitly stated that they use mobile phones. Finally, talking about economic needs for access to extra services, ten people indicated that they were able to meet their expenses on a regular basis every month, while three indicated that they were not (Participants 5, 18 and 20).

In qualitative open answers, they explained: "No, because I normally went out of the house very little, plus my children help her" (Participant 12); "I changed because of my state of health, not because of Covid" (Participant 29); "I am the same as before" (Participant 22). Among those who said that these needs changed, they indicated, for example: "I need my daughters to do my shopping" (Participant 26); "I changed in terms of my social networks" (Participant 33); "as I am undergoing chemotherapy, I am recommended to walk, but I go out with great caution" (Participant 20).

3.4 Health perception

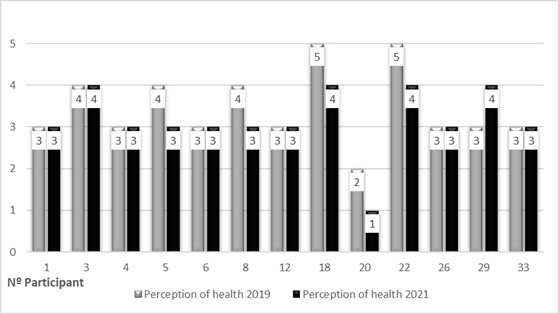

A Likert scale was used to measure the perception of health status, where 1 means "very bad" and 5 means "very good". It showed a somewhat lower mean in 2021 ( = 3.15 SD = 0.87), compared to 2019 ( = 3.46 SD = 0.80), and with a median of three points in both years. Eight participants rated it as "fair", one as "very poor", and four as "very good". Figure 1 shows the comparison of this perception in the years 2019 and 2021, for each participant. Seven interviewed people maintained their perception between these years, five indicated that it decreased, and one person scored higher. Looking further into the possible causes of Participant 20's getting worse health perception, the fact that he was receiving chemotherapy at the time explained this change, knowing, moreover, that he previously had another cancer diagnosis.

Figure 1. Participants' perception of health in 2019 and 2021

Note. 1= Very Bad 2= Bad 3= Fair 4= Good 5= Very Good.

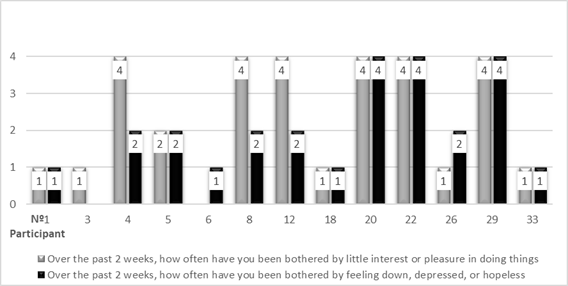

In relation to their health status in the previous week, participants experienced little interest or pleasure in doing things. We obtained the following results in terms of mean and standard deviation: = 2.58; SD = 1.50. And they also felt discouraged, depressed or hopeless: = 2.17; SD = 1.19. More specifically (see Figure 2), three participants had maximum scores in both losses of pleasure and discouragement (Participants 20, 22 and 29). And Participants 4, 8 and 12 obtained maximum scores in feelings of discouragement. Participant 20 stood out in terms of health decline, as he indicated that he is currently receiving chemotherapy. Additionally, 15 years earlier, he underwent surgery for colon cancer, and his health has been declining since, according to this participant.

Figure 2. Perceived frequency of disinterest and discouragement.

Note. Scale: 1 = Not at all 2 = Several days 3 = More than half of the days 4 = Nearly every day

Regarding the quantitative results concerning the impact on health due to the Covid-19 situation, five participants indicated that it did not affect them, while others indicated that it affected them in some way (see Table 4). About whether the person could adapt both inside and outside their home, the majority of respondents said that they could protect themselves inside their environment, unlike outside the home, where they might need help.

Table 4. Health status and health condition in COVID-19 situation for each participant (P)

|

Participant |

How is your health? |

How has this situation affected your health? |

|

1 |

I have osteoarthritis, body pain at night and

headaches, and my blood pressure is regulated. |

I am happy because, although I have not gone

out, I like my house. |

|

3 |

Sugar, dizziness, lightheadedness |

|

|

4 |

Swollen legs; shuffling of feet. |

|

|

5 |

Not very well, tired, tired legs |

|

|

6 |

I am fine but a bit worse since I had a fall a

year and a half ago. |

I don't think it has affected me, only that I

have walked less. |

|

8 |

I have bad knees, and the "curve" is

bad for me, I also have diabetes, which causes low blood sugar, I measure my

blood sugar three times a day. |

It has affected me because of the sadness I

suffer from. |

|

12 |

Going to days, have decalcification of bones. |

I used to eat with my children, but since my

daughter-in-law works at the hospital [...] and my granddaughter is a nurse,

we see each other as little as possible to avoid contagion. |

|

18 |

Just had a headache |

It has not affected me |

|

20 |

I have undergone thyroid surgery and a biopsy

and also has cancer and respiratory insufficiency. |

Yes, because of fear, psychologically it affects

me. |

|

22 |

I have a pacemaker, have had surgery on her

uterus, have pains in my leg. |

I think that this is not good for anyone and

that it will have consequences, I think that it has affected me

psychologically quite a lot. |

|

26 |

I have heart problems, apnoea and a hiatus

hernia. |

My health was worse than before |

|

29 |

I am well, but have mobility problems. |

It has not affected |

|

33 |

I am well. |

I have not been affected, I am as before. |

3.5 Social-relational

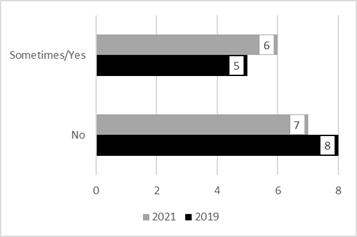

Participants were asked about the variables linked to the perception of loneliness in two different ways, in order to achieve greater precision in their answers and to observe possible contradictions in their responses. On the one hand, by means of a direct question and on the other hand, by means of the De Jong scale (Buz & Prieto, 2013; Tomás et al., 2017). Figure 3 shows the answers to the direct question on whether or not they feel lonely, comparing the years 2019 and 2021, in which a slight increase in loneliness can be seen in 2021.

Figure 3. Experiencing loneliness on a day-to-day basis

Regarding the De Jong scale (Buz & Prieto, 2013; Tomás et al., 2017), descriptive statistics show a slight increase in the mean, between 2019 and 2021 (2019: = 2.15; SD = 1.63 - 2021: = 2.54; SD = 1.56). With respect to the median, it increased from two to three points, respectively. With respect to subscales of De Jong scale, both the social subscale as well as emotional subscale showed an increase, though it was not statistically significant: social subscale (2019: =1.30; SD = 0.94 - 2021: = 1.46; SD = 1.05); emotional subscale (2019: = 0.84; SD = 0.98 - 2021: = 1.08; SD = 1.04).

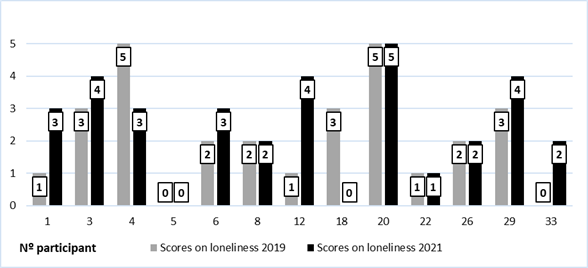

Considering each of the participants, six increased their perception of loneliness, four maintained it, and three decreased it (see Figure 4). The highest scores in 2021 correspond to a total of seven participants: 3, 12, 20, and 29, with scores of 4 and 5 points; and participants 1, 4, and 6, with 3 points. In terms of gender, among men, the variation was equally distributed between those who increased, equalised and decreased their score (33%). In the case of women, 50% increased their perception of loneliness, 40% maintained their perception and only 10% decreased their score.

Figure 4. De Jong scale loneliness scores per participant, years 2019 and 2021

When the variable "feeling lonely in everyday life" is related to having children, three of the four participants who do not have children felt lonely "sometimes". Among the nine participants who have sons, two said that they "do" feel lonely. In relation to the question of whether the participants would like to receive visitors, in 2021 seven gave a positive answer about this, compared to four in 2019. Among the participants who indicated that they felt lonely on a daily basis in 2021, four of them (all the men and one woman) would like to be visited (Participants 3, 8, 12 and 20). On leisure-time, 10 people indicated that they did engage in some activity, and three responded that they did not engage in any activity.

Nine participants were practising a religion, and they indicated that although they were not able to go to mass as before (at the church, for example), they were able to continue the practice of the belief, either through television, radio, or prayer. When linking the practice of a religion to loneliness scores, those who were practitioners had a median loneliness score of two points, while those who were not practitioners had higher loneliness scores, with a median of four points.

In relation to the social-relational aspect, participants mostly had contact with their sons and daughters, neighbours and other relatives, on a daily or weekly basis (see Table 5). As for the form of contact with the aforementioned people, it was mostly face-to-face or in person and by telephone. When talking about entities or administrations that contacted the participants, they mentioned that it was mainly the managers of the TC and HHS services, which they are users of. Therefore, none of the participants seemed to suffer from a severe form of social isolation, as they maintain interactions with other people, as well as with the TC and HHS services.

Table 5. Characteristics of the contact maintained by the participants

|

Persons with whom you have had contact during the

COVID-19 situation |

f |

|

|

|

|

Children

living away from home |

9 |

|

Neighbours |

7 |

|

Grandchildren

living away from home |

6 |

|

Daughter-in-law

and/or sons-in-law |

5 |

|

Other family |

4 |

|

Friends or

acquaintances |

3 |

|

Frequency

of contact with these people |

|

|

Almost every day |

10 |

|

Approximately weekly |

8 |

|

Occasionally |

2 |

|

Approximately monthly |

1 |

|

Never |

0 |

|

Contact

from administrations or entities |

|

|

Teleassistance (TS) |

11 |

|

Home Help Service

(HHS) |

6 |

|

Health centre |

2 |

|

Municipal

Social Services Centre (CMSS) |

2 |

|

Others:

(Neighborhood Associations; ZaragozaVivienda,

etc.) |

2 |

|

Elderly care office |

1 |

3.6 Perception of risk and coping

Concern and perceived stress were rated on a scale of 1 to 5 on the perception of risk within the Covid-19 experience (get sick, death, etc.), where 1 means "nothing" and 5 means "very much". In general, the scores were not very high, below 3 points on average (Worry: = 2.58; SD=1.83; Stress perception: = 2.0; SD=1.35). However, nine participants pointed out that they have stopped doing certain activities, such as going to places, and seeing people, among others, because of the Covid-19. Thus, there were four main avoidance behaviours that they were not able to do:

· Attend mass (Participants 3, 8, 33 and 26)

· Go out for a walk or exercise (Participants 3, 6, 20, 22, 26, 33)

· Socialise with friends or family (Participants 3, 8, 33, 26)

· Activities such as workshops, or at the elderly person's home (Participants 22 and 33).

In relation to how they coped with the situation, participants indicated some behaviours, grouped into six categories:

· Watching television (Participants, 1, 3, 4, 8, 18, 20, 33)

· Reading (Participants 8, 20, 26, 33)

· Praying (Participants 4, 26)

· Entertaining (e.g., crossword puzzles, painting) (Participants 1, 5, 20, 26)

· Miscellaneous errands to walk more (Participant 1)

· Talking more on the phone (Participant 33).

Table 6 shows open-ended comments from participants' experiences, as well as interviewer annotations, which provide a wealth of information useful to better identify some potential risk factors. Thus, some issues are derived from these excerpts: The need for communication and social relationships (Participant 1, 3, 12, 18, 20), satisfaction/dissatisfaction with institutions (Participant 6, 33), use of coping strategies (Participant 20, 22), aging and health problems (Participant 20, 29), and satisfactory family relationships (Participant 18, 22, 26). In addition, a detailed analysis of some participants' responses helps us to visualise some patterns, potentially useful for future interventions. For example, as a factor at the individual level, Participant 12 noted: "I would like people to come and visit me, because when I was young, I was used to being with a lot of people". Participant 1 showed a strong need to explain everyday stories, in contradiction to her responses, for example, of not wanting visitors. Participant 20, who had a complicated health situation, did not have children, did not seem to sleep well, scored high in loneliness, disinterest, and discouragement, and would like to receive visits. This indicated that the situation affected him psychologically due to the fear of becoming ill and the need for support (which his children could have provided, had he had any). Similarly, Participant 29, childless, with significant mobility problems, using a wheelchair since 2020. Although she perceived her health as good, she scored high on disinterest and discouragement, and showed a high perception of loneliness. She reported a long-standing feeling of emptiness throughout her life. However, she reported that he did not wish to receive visitors. She pointed out that she has become accustomed to not having much contact with people, that she has always felt lonely, and that “it is worse to feel lonely in company than when she is voluntarily alone”. She also said that her main problem is not so much Covid-19, because she did not go out much, but rather her mobility problems.

Table 6. Notes collected by interviewers (professionals) during the interview

|

Participant |

|

|

1 |

Enormous

need to talk, although contradictory to not needing to be visited. She seems

to enjoy talking and telling stories of what happens to her in everyday life,

with her family, etc. |

|

3 |

Difficulties

in understanding. He misses his wife. Compares the current situation with the

situation during the war. |

|

6 |

She is

happy with the institutions because they have treated her well. She is happy

that her HHS assistant has been the same since the beginning. On Christmas

Eve they brought her dinner and she liked it. She has never stopped doing

things. If she did, she thinks it would get worse. Weakness in arms and hands. |

|

12 |

She

would like people to come and visit her, when she was young she was used to. |

|

18 |

He has

no children, but his niece is more than a daughter to him. Therefore, it's as

if he did have children. You can see that he feels like sharing some

experiences that have happened to him, (e.g., a problem he had some time ago

with a doctor) and about a hospital admission he had some time ago. |

|

20 |

Many

days, at 4-5 in the morning, listening to the radio because he can't sleep.

"Music calms the beasts," he says. Every day I put on the radio and

stop thinking and listen. He is currently undergoing chemotherapy. He also

underwent surgery for colon cancer 15 years ago, and his health declined. |

|

22 |

The

daughter eats with her every day, because she lives downstairs. She likes to pray. |

|

26 |

Two

daughters, face-to-face contact, every day. She does pedalling. She has been

alone for many years and is used to. |

|

29 |

It is

worse to feel lonely when you are accompanied than when you choose to be

alone. She has been in a wheelchair since March 2020 (1 year) approx. At home

with a crutch, outside with a wheelchair. Feels a lifelong sense of

emptiness. Takes sleeping pills. She does not feel affected by COVID-19,

because she does not go out much. What

has affected her is her mobility problem. |

|

33 |

Finally,

she comments on how unhappy she is with the medical service. She says that

she fell in the street on a raised tile and broke her shoulder. She filed a

complaint but could not send a photo because it was a tile that moved. The

police helped her and filed a complaint. The council reviewed the

documentation but have not replied and it has been two years. Social Worker

offers to review what has happened with her request. |

4 Discussion

This study analyses the experiences of users from the MSSC Arrabal, within the framework of collaboration between social services and the university. Therefore, the aim of the study was to investigate how some MSSC users experienced the COVID-19 situation, to determine whether it had an impact on their psychosocial needs in different areas, with the goal of promoting better intervention in the prevention and response to unwanted loneliness among elderly people. To achieve this, a mixed-methods study was conducted, paying special attention to those participants who might need assistance, providing social workers with a better diagnosis of the situation of vulnerable elderly individuals at risk of unwanted loneliness.

Our findings have revealed the following issues. Firstly, an aspect common to all the participants, is that they were principally women, lived alone and were beneficiaries of the HHS service and the TC.

Secondly, in relation to: daily life, access to services in general; and in relation to the impact caused by the Covid-19 situation, the participants perceived relatively few changes, apart from not being able to go out frequently. Based on the participant responses, it can be stated that their life was not significantly different from the situation resulting from Covid-19. That is, the lockdown situation did not cause significant changes in the activities and contacts they had in their daily lives. Lebrasseur et al., (2021) observed conflicting findings regarding the impact of Covid-19 on this population, highlighting that the pandemic resulted in relatively minimal changes to their daily lives as compared to pre-pandemic times.

In addition, our participants were helped by their sons and daughters on the one hand; and, by the HHS and TC services on the other hand, with which the vast majority are happy. Both these services and the interaction, especially with sons, may be serving as protective elements. Most of the participants indicated that they were able to meet expenses on a regular basis, and in general, they indicated that their needs were covered. In terms of communication, apart from mobile phones, participants did not use technologies such as the internet. In this regard, it can be stated that, when making interventions, it would be preferable to conduct them through more traditional means such as face-to-face or phone communication.

Contrasting the quantitative and qualitative results, although the quantitative data seem to indicate that needs are covered, the qualitative data highlights a lack of income, as most participants only had their retirement/widow’s pension. Additionally, some mentioned needing help with tasks such as grocery shopping, which was not covered by the HHS. Therefore, interventions should aim to promote the inclusion of this service in the HHS catalogue and strengthen community ties that enhance the support network for these types of tasks.

Thirdly, the data showed a slight deterioration in perceptions of health status, someone related to the aging processes and in one case with an oncology process. In respect of the effect on health due to the pandemic situation, although there are heterogeneous responses, those who indicated that there was an effect focus on different facts: they were not able to go out much, to go for walks or exercise; they saw less of some family members; while other people indicated that their health has not been affected, not feeling significant changes compared to their state prior to the pandemic. On the perception of disinterest and discouragement, mean scores were not high, but some individual participants did show high scores on both dimensions, principally those who had a chronic disease or a mobility trouble. In this sense, research has also shown that individuals living with frailty and health conditions such as chronic diseases or disabilities during the Covid-19 pandemic may experience increased vulnerability to the challenges of isolation, worry, and loneliness due to their existing vulnerabilities (Aartsen, Rothe & Von Kügelgen, 2023; Baarck & Kovacic, 2022; Gruiskens et al., 2023; Joseph et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2022).

Fourthly, in the social-relational dimension, the frequency of regular contact with children and family members, also neighbours, as well as contact with the HHS and the TC, stood out by phone and TC system. The experience of loneliness in everyday life increased from 2019 to 2021, and also there was a trend of increasing scores on the loneliness scale in half of the participants. This increasing was slightly both in total scale as well as in social and emotional subscales. Similarly, the majority of studies noted increased levels of loneliness during Covid-19 comparing to prior the pandemic, however, the results are mixed and inconclusive (Beadle, Gifford & Heller, 2022; Ernst et al., 2022; Bhutani & Greenwald, 2021) due to the high heterogeneity within the elderly population (Kulmala et al., 2021). Nevertheless, the professionals who conducted the interviews pointed out in their comments (Table 6) that in some cases there were contradictions, as participants would verbalize not feeling lonely and having sufficient social relationships, but then they did not want the professionals to leave their homes, invited them for coffee, asked them more questions, etc. This point highlights that the perception of unwanted loneliness remains something difficult to socially accept due to its stigmatization.

Fifthly, risk perception scores for the Covid-19 situation were low, although participants did engage in avoidance behaviours, of places or people, as a form of protection from pandemic risk. Coping strategies seem to play a role here. Some studies have noted it (Fuller & Huseth-Zosel, 2021; Kadowaki & Wister, 2023; Lozano & Gallardo, 2022) in the sense that older adults in Covid-19 have had the ability to shape the lived situation and transform leisure time into activity, this proactive coping is a possible strong resilience factor for stress, especially when older adults were compared to younger adults (Pearman et al., 2021).

Although the overall scores for aspects such as loneliness, depression, or stress are not high, as well as various psychosocial needs, the results (qualitative and quantitative) of some participants described in the findings do show risk situations. Therefore, there is an interaction between risk factors (e.g., health status, living alone, lack of emotional and social support, among others) that may be amplified by the Covid-19 situation, which shows the great variability in the responses to the pandemic situation (Kulmala et al., 2021; Özdemir & Çelen, 2023). This coincides with previous literature, which highlighted the need to consider the specific combination and accumulation of risk factors affecting the individual, as the mechanisms of loneliness are multifactorial and can vary based on situational, demographic, and individual differences (Beadle, Gifford & Heller, 2022; Bu, Steptoe & Fancourt, 2020).

4.1 Limitations and future research

This study has several limitations that should be considered. Although the results from the qualitative part can be considered sufficient, the same cannot be said for the quantitative data and the validation of the instruments due to the small sample size, even though this was not the main focus of the study. The advanced age of some participants (median age of 86) posed challenges in answering interview questions due to factors such as hearing difficulties and uncertainties regarding scale-type questions. Additionally, alternatives to face-to-face interviews, such as telephone interviews, should be considered. Despite these limitations, the participants generally felt comfortable during the interviews and shared their experiences openly. Some level of loneliness emerged as a common theme, highlighting a need for companionship that was not explicitly expressed despite the absence of high loneliness scores.

Based on these limitations, future research should aim to increase the number of participants from the same or different neighbourhoods to expand the database. The use of simplified standardized scales would facilitate data collection from older adults with cognitive and sensory impairments, ensuring accurate and reliable measurements that accommodate their unique needs. It is also crucial to develop strategies to overcome barriers to evidence-based practice in social work, such as addressing time constraints and administrative practices that hinder its implementation (Drisko & Grady, 2019; Pereñiguez, 2012; Scurlock-Evans & Upton, 2015).

5 Conclusions

This study examines the impact of the situation caused by COVID-19 on the psychosocial needs, focusing on loneliness and social isolation, of a selection of MSSC users (HHS and TC services). To this end, we have achieved the goal of applying a first pilot instrument in practice to detect the needs and perceptions of loneliness in this situation. The professionals at the MSSC continue to use this tool and report that it is useful in their daily work. Through this tool, they are able to gather evidence on aspects such as social relationships and the support network of elderly individuals, facilitating the diagnosis of the need to strengthen community support; their perception of health status, which can be cross-checked with actual medical data, thus reflecting possible issues; their satisfaction with the services they receive, and therefore the utility of these services and whether they need to be modified or expanded; and the activities they can engage in on a daily basis, facilitating the diagnosis regarding their occupation and the possibility of complementing them with, for example, healthy aging activities, among others.

Specifically, the results related to detecting psychosocial needs indicate that, in general, participants perceived relatively few changes in their daily lives due to COVID-19. In this sense, regarding the third of our objectives, this can be attributed to the significant social support provided by their children, family, and social services, which played a crucial role in maintaining a reasonably normalized daily life. However, it is important to note that health problems and chronic illnesses were identified as variables that had a more negative impact on the feelings of loneliness and social isolation of participants, as well as other issues. The results shed light on the experiences of the participants and contribute to the development of more effective interventions by social services, such as promoting healthy aging activities, the preference for telephone and in-person interventions over technological ones, and the need to review HHS benefits to include aspects such as help with grocery shopping. This highlights the need for personalized interventions that address the unique challenges faced by individuals with health problems.

5.1 Contributions

Several contributions can be made based on the findings of this study. 1) This study contributes to providing a comprehensive and individualized map of the needs of social service users in the MSSC, which facilitates the detection of risk factors and promotes the development of more individualized interventions. This is a small local study that has the potential to expand its development, both within the community itself and to other settings with larger and more diverse samples. 2) Although the small sample size has prevented the validation of the employed instrument, this initial tool for detecting unwanted loneliness in older adults serves as a starting point for its optimization, with the potential to develop, in the near future, a tool tailored to the needs of social services for their elderly users, contributing to improving decision-making in the future. 3) From a methodological point of view, the use of a mixed-method approach contributes to this study in both dimensions. On the one hand, the qualitative approach, as Wigfield and Alden (2018) point out, allows: a) to better consider the heterogeneity of the construct loneliness, which can help to address aspects closely linked to the local area (e.g. in a particular neighbourhood area); b) to consider and have a better understanding of the diverse needs, contexts, and influencing factors on older people, who may experience loneliness and social isolation (Akhter-Khan & Rhoda, 2020; Dare et al., 2019); c) to consider users' experiences with the functioning of social services. On the other hand, the quantitative approach allowed us to support the systematization of these experiences and create a database with future potential for detecting patterns in the MSSC. 4) The research contributes, to a certain extent, to the body of knowledge on the impact of COVID-19 on the psychosocial well-being of MSSC Arrabal users. By recognizing the significance of social support, acknowledging the challenges posed by health conditions, and emphasizing the potential for broader applicability, this research informs the development of evidence-based interventions by the MSSC Arrabal. 5) By establishing a collaborative link between social services and the academic world, gerontological social work is empowered (Lozano & Gallardo, 2022), aiming to adopt an evidence-based approach (Jones & Sherr, 2014). This collaborative effort significantly contributes to the shared goal of improving service delivery to users, enhancing their overall experience. In conclusion, all of this enables the development of future interventions that align with the principle of "one size does not fit all," emphasizing person-centred approaches, as suggested by the scientific community.

5.2 Acknowledgements

We acknowledge financial support from the Regional Government of Aragón and the European Social Fund (project S16_20R). Data collection and preliminary analysis were supported by the Arrabal Municipal Social Services Centre (MSSC), Zaragoza City Council (Spain).

References:

Aartsen, M., Rothe, F. & von Kügelgen, M. (2023). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on social isolation and loneliness. A Nordic research review. Nordic Welfare Centre. https://nordicwelfare.org/en/publikationer/the-impact-of-the-covid-19-pandemic-on-social-isolation-and-loneliness-a-nordic-research-review/.

Adler, N.E. & Stead, W.W. (2015). Patients in context—EHR capture of social and behavioural determinants of health. Obstetrical & Gynaecological Survey, 70(6), 388-390. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ogx.0000465303.29687.97.

Akhter-Khan, S.C. & Rhoda, A. (2020). Why Loneliness Interventions Are Unsuccessful: A Call for Precision Health. Advances in Geriatric Medicine and Research, 2(3), https://doi.org/10.20900/agmr20200016.

Baarck, J. & Kovacic, M. (2022). The relationship between loneliness and health. Publications Office of the European Union. https://dx.doi.org/10.2760/90915.

Beadle, J. N., Gifford, A. & Heller, A. (2022). A narrative review of loneliness and brain health in older adults: Implications of covid-19. Current Behavioural Neuroscience Reports, 9(3), 73-83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40473-021-00237-6.

Berg-Weger, M. & Morley, J.E. (2020). Loneliness and social isolation in older adults during the covid-19 pandemic: Implications for gerontological social work. The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging, 24(5), 456-458. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-020-1366-8.

Bhutani, S. & Greenwald, B. (2021). Loneliness in the elderly during the covid-19 pandemic: A literature review in preparation for a future study. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 29(4), S87-S88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2021.01.081.

Bu, F., Steptoe, A. & Fancourt, D. (2020). Who is lonely in lockdown? Cross-cohort analyses of predictors of loneliness before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Health, 186, 31-34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2020.06.036.

Buecker, S. & Horstmann, K. T. (2021). Loneliness and social isolation during the covid-19 pandemic. European Psychologist, 26(4), 272-284. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000453.

Buz, J. & Prieto, G. (2013). Análisis de la escala de soledad de Jong gierveld mediante el modelo de rasch. Universitas Psychologica, 12(3). https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.UPSY12-3.aesd.

Campaign to end loneliness (2021). Loneliness beyond Covid-19 Learning the lessons of the pandemic for a less lonely future. https://www.campaigntoendloneliness.org/wp-content/uploads/Loneliness-beyond-Covid-19-July-2021.pdf.

Creswell, J.W. & Creswell, J.D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. SAGE.

Creswell, J.W. & Plano Clark, V.L. (2018). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. SAGE.

Dahlberg, L. (2021). Loneliness during the COVID-19 pandemic, Aging & Mental Health, 25, 1161-1164. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2021.1875195.

Dahlberg, L., McKee, K. J., Frank, A. & Naseer, M. (2022). A systematic review of longitudinal risk factors for loneliness in older adults. Aging & Mental Health, 26(2), 225-249. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2021.1876638.

Dare, J., Wilkinson, C., Donovan, R., Lo, J., McDermott, M.-L., O’Sullivan, H. & Marquis, R. (2019). ‘Guidance for research on social isolation, loneliness, and participation among older people: Lessons from a mixed methods study’, International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 18, https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406919872914.

Drisko, J.W. & Grady, M.D. (2019). Evidence-based practice in clinical social work. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-15224-6.

Ernst, M., Niederer, D., Werner, A. M., Czaja, S. J., Mikton, C., Ong, A. D., Rosen, T., Brähler, E. & Beutel, M. E. (2022). Loneliness before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review with meta-analysis. American Psychologist, 77(5), 660. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0001005.

Fuller, H. R. & Huseth-Zosel, A. (2021). Lessons in resilience: Initial coping among older adults during the covid-19 pandemic. The Gerontologist, 61(1), 114-125. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnaa170.

Gruiskens, J. R. J. H., van Hoef, L., Theunissen, M., Courtens, A. M., van den Beuken – van Everdingen, M. H. J., Gidding-Slok, A. H. M. & van Schayck, O. C. P. (2023). The psychosocial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on chronic care patients. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 24(4), 426-433.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2023.01.003.

Holt-Lunstad, J. (2021). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors: The power of social connection in prevention. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 15(5), 567-573. https://doi.org/10.1177/15598276211009454.

Jones, J.M. & Sherr, M.E. (2014). The role of relationships in connecting social work research and evidence-based practice, Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work, 11(1-2), 139-147. https://doi.org/10.1080/15433714.2013.845028.

Joseph, C. A., Kobayashi, L. C., Frain, L. N. & Finlay, J. M. (2023). “I can’t take any chances”: A mixed methods study of frailty, isolation, worry, and loneliness among aging adults during the covid-19 pandemic. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 42(5), 789-799. https://doi.org/10.1177/07334648221147918.

Kadowaki, L. & Wister, A. (2023). Older adults and social isolation and loneliness during the covid-19 pandemic: An integrated review of patterns, effects, and interventions. Canadian Journal on Aging / La Revue Canadienne Du Vieillissement, 42(2), 199-216. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980822000459.

Kulmala, J., Tiilikainen, E., Lisko, I., Ngandu, T., Kivipelto, M. & Solomon, A. (2021). Personal Social Networks of Community-Dwelling Oldest Old During the Covid-19 Pandemic-A Qualitative Study. Frontiers in public health, 9, 770965. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.770965.

Lebrasseur,

A., Fortin-Bédard, N., Lettre, J., Raymond, E., Bussières, E.-L., Lapierre, N.,

Faieta, J., Vincent, C., Duchesne, L., Ouellet, M.-C., Gagnon, E., Tourigny,

A., Lamontagne, M.-È. & Routhier, F. (2021).

Impact of the covid-19 pandemic on older adults: Rapid review. JMIR Aging, 4(2), e26474. https://doi.org/10.2196/26474.

Lim, M.H., Eres, R. & Vasan, S. (2020). Understanding

loneliness in the twenty-first century: An update on correlates, risk factors,

and potential solutions, Social Psychiatry and

Psychiatric Epidemiology, 55(7), 793-810. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01889-7.

Lozano Benito, A. & Gallardo Peralta, L. P. (2022). Soledad y bienestar emocional en mujeres mayores. Diversas experiencias durante el confinamiento en Bilbao. Alternativas. Cuadernos de Trabajo Social, 29(2), 208. https://doi.org/10.14198/ALTERN.20221.

Mayring, P. (2014). Qualitative content analysis: theoretical foundation, basic procedures and software solution. Klagenfurt.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine (NASEM) (2020). Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults: Opportunities for the Health Care System. The National Academies Press.

Özdemir, P. A. & Çelen, H. N. (2023). Social loneliness and perceived stress among middle-aged and older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04301-0.

Pearman, A., Hughes, M. L., Smith, E. L. & Neupert, S. D. (2021). Age differences in risk and resilience factors in covid-19-related stress. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 76(2), e38-e44. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbaa120.

Pereñiguez Olmo, M. D. (2012). Trabajo Social e investigación: La

práctica basada en la evidencia. Revista de Trabajo

Social de Murcia, 17. http://repositorio.ucam.edu/handle/10952/3359.

Pinazo-Hernandis, S. (2020). Impacto psicosocial de la COVID-19 en las

personas mayores: Problemas y retos. Revista Española de

Geriatría y Gerontología, 55(5), 249-252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regg.2020.05.006.

Prohaska, T., Burholt, V., Burns, A., Golden, J., Hawkley, L., Lawlor, B., Leavey, G., Lubben, J., O’Sullivan, R., Perissinotto, C., Tilburg, T. van, Tully, M., Victor, C. & Fried, L. (2020). ‘Consensus statement: Loneliness in older adults, the 21st century social determinant of health?’, BMJ Open, 10(8), e034967. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034967.

Scurlock-Evans,

L. & Upton, D. (2015). ‘The role and nature

of evidence: A systematic review of social workers’ evidence-based practice

orientation, attitudes, and implementation’, Journal of

Evidence-Informed Social Work, 12(4), 369-399. https://doi.org/10.1080/15433714.2013.853014.

Tomás, J. M., Pinazo-Hernandis, S., Donio-Bellegarde, M. & Hontangas, P. M. (2017). Validity of the de Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale in Spanish older population: competitive structural models and item response theory. European journal of ageing, 14(4), 429–437. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-017-0417-4.

Van Tilburg, T.G., Steinmetz, S., Stolte, E., van der Roest, H. & de Vries, D.H. (2021). ‘Loneliness and mental health during the covid-19 pandemic: A study among Dutch older adults’, The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 76(7), e249-e255. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbaa111.

Wang, Y., Lin, P., Lin, Y., Lee, Y., Wang, J., Chen, Y. & Yang, S. (2022). Factors influencing loneliness among older people using homecare services during the COVID ‐19 pandemic. Psychogeriatrics, 23(2), 252-260. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyg.12927.

Wigfield, A. & Alden, S. (2018). ‘Assessing the effectiveness of social indices to measure the prevalence of social isolation in neighbourhoods: A qualitative sense checks of an index in a northern English city’, Social Indicators Research, 140(3), 1017-1034. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-017-1812-0.

World Health Organization (2021). Social isolation and loneliness among older people: advocacy brief. https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1358663/retrieve.

Author´s Address:

Marta Mira-Aladrén

Faculty of Social and Labour Sciences, University of Zaragoza, Social Capital

and Wellbeing Research Group

Institute for Research in Employment, Digital Society and Sustainability

(IEDIS)

Violante de Hungría 23, 50009 Zaragoza, Spain

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6088-0324

mmira@unizar.es

Author´s Address:

Azucena Díez Casao

Arrabal Municipal Social Services Centre (MSSC)

Zaragoza City Council

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4766-3170

Author´s Address:

Pilar Sanz Martínez

Arrabal Municipal Social Services Centre (MSSC)

Zaragoza City Council

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6038-9239

Author´s Address:

Victoria Pérez Fernández

Arrabal Municipal Social Services Centre (MSSC)

Zaragoza City Council

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2918-5937

Author´s Address:

Inmaculada Leonarte Sánchez

San José Municipal Social Services Centre (MSSC)

Zaragoza City Council

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5402-7941

Author´s Address:

Javier Martín-Peña

Faculty of Social and Labour Sciences, University of Zaragoza, Social Capital

and Wellbeing Research Group

Violante de Hungría 23, 50009 Zaragoza, Spain

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3393-2061