Contingencies for Intercultural Dialogue in Virtual Space: An Empirical Research on the Role of Internet in Fostering Intercultural Competences from the Perspective of Migrant Youth

Abstract

Against the background of the emerging multicultural migration society, acquisition of intercultural competences is getting vitally important for youngsters to actively and effectively engage with intercultural dialogue in a co-existent life context. Contingencies for such intercultural dialogue and to foster intercultural competences of youngsters are opened in virtual space when youth with different ethnic, social and cultural background go online. However, differences in Internet use and competences acquisition as “digital inequality” also exist among youth with different socio-cultural background. This article reports on a quantitative survey of 300 Turkish migrant youth in Germany as empirical sample about how Internet use generally fosters their intercultural competences, what differences exist among them and which indicators can explain the differences. Preliminary findings show that the contingencies of Internet in fostering intercultural competences are still not much employed and realised by Turkish migrant youth. Four online groups connected with bonding, bridging, both (bonding and bridging) and none socio-cultural networks are found out based on the cluster analysis with SPSS. These different networks, from the perspective of social cultural capital, can explain the differences concerning development of intercultural competences among them. It is indicated in this research that many Turkish migrant youth still lack recognition and capabilities to construct their intercultural social networks or relations through using Internet and further to employ the relations as intercultural social capital or social support in their life context. This therefore poses a critical implication for youth work to help migrant youth construct and reconstruct their socio-cultural networks through using Internet so as to extend social support for competences acquisition.

1 Background: necessity of intercultural dialogue and potential of Internet to foster intercultural competences of young people

Nowadays in the growing migration society, social work and youth work has to be confronted with the emerging multicultural context. In many social spaces of youngsters, for example in youth centres, young people with different ethnic and cultural backgrounds come and grow up together. This necessitates intercultural dialogue or cultural interchange among youth both native and migrant for a common co-existent life context in a micro level as well as for a democratic multicultural society in a macro level.

Intercultural dialogue is not only a necessity in a migration society. It also constitutes a critical perspective, theoretically and politically, to reflect on the existent strategies dealing with migration problems in which social and educational inequalities of migrant youth have been perpetuating. Following the critical multiculturalism, it is the “normalisation and universalization” (May 1999) of the culture of the dominant ethnic majorities that decides the hidden unequal power relationships which help to explain the perpetuating inequalities of migrant people. In this context, without intercultural dialogue, only the one-sided social integration or assimilation of migrant minorities into the majority hosting society cannot radically enhance the equal social cultural situations of migrant minorities since their culture is not equally considered and developed in a common co-existent social context.

Therefore, in the context of a growing requirement for “reflective interculturality” (Hamburger 2006), it is necessary for youth work to foster intercultural competences of young citizens with which they are capable of critically engaging with all ethnic and cultural background, including their own (May 1999), initiating as well as participating in intercultural dialogue with people of different social cultural background, and achieving a multicultural life world.

Nowadays with young people’s increasing engagement with Internet in their everyday life contexts, Internet has been playing an important role in their “Bildung [1] ” or educational processes and competences development. On the one hand, Internet not only extends opportunities for young people to easily access multicultural knowledge. Through the independence on time and space and the anonymity of using, it also enables more possibilities in virtual space for youth to contact and communicate with people of different social cultural and ethnic backgrounds. This can further extend the socio-cultural networks of young people as “social support” (DiMaggio and Hargittai 2001) inside or beyond different virtual communities [2] . As the research of Sørensen et al. (2007) shows, when young people use Internet, often the case interacting with each other through writing emails or chatting, they establish informal learning networks through which they exchange opinions, share knowledge with one another, and solving problems together. The extended social support is helpful particularly for those disadvantaged migrant youth to learn and acquire competences in an informal learning context. In addition to the extension of networks, what is even more critical in the process of online interaction is the “diversification” (Mesch 2007) of youngsters’ social cultural networks potentially enabled by interacting with individuals of different characters like social, ethnic and cultural backgrounds. This means that their online communication is much likely to be related with as well as influenced by their cultural background, for instance, learning languages from each other, sharing and understanding knowledge of their ethnicities, exchanging cultural opinions, and even dealing with and reflecting on cultural conflicts etc. In this way, contingencies are opened for intercultural dialogue and development of intercultural competences especially between migrant youth and native peers in the virtual space. The social support based on the diversified socio-cultural networks accordingly can also be in form of intercultural social support. Through the extended intercultural dialogue as well as intercultural social support, online interaction can provide important opportunities to break the normalisation of the culture of the dominant majorities and then to reduce the perpetuating inequalities of migrant people.

However, on the other hand, Internet simultaneously also functions as differentiating. Quiet a few studies on “digital inequality” (see e.g. Bonfadelli 2002 and 2006; Livingstone et al. 2004; KIB [3] 2004 and 2006 etc.) have shown differences in Internet use and competences acquisition among youth with different social demographical backgrounds. The classical indicators like formal educational level, age, gender and migration background etc. are important factors to interpret the differences of Internet use as reproduction of social inequality. However, so far there has not been much research concerning development of intercultural competences through using Internet. Thus we still lack understanding about whether there are also differences in intercultural competences development and what indicators can interpret the differences. Concerning intercultural competences which are fostered by online interaction, online socio-cultural networks can also be an indicative factor to affect intercultural dialogue and acquisition of intercultural competences compared to the classical social demographical indicators. As mentioned by Norris (2002), Internet plays as both “bonding networks” of social and cultural homogeneity and “bridging networks” of social and cultural heterogeneity. Under different network-based support, the development of intercultural competences of young people through employing contingencies of Internet is assumed to be different. Their capabilities to break the normalisation of the dominant ethnic culture thus will also be differentiated.

Against the background of the rising intercultural virtual space as a crucial part of young people’s lifeworld context and considering its positive aspects as well as limitations regarding fostering intercultural competences, at issue it is critical to explore firstly what contingencies are exactly enabled by using Internet for young people especially for migrant youth to develop intercultural competences and secondly to question how the contingencies are differently developed by youth under which influential factors?

2 Theoretical approach of intercultural competences in terms of intercultural dialogue under the influence of socio-cultural networks

2.1 Definition and analytical structure of intercultural competence

To survey the two questions, firstly it is necessary to define intercultural competence so as to operationalize it in this research. Here it is important to point out that intercultural competences are essential for both native and migrant youth in a migration society. But this research is only concentrated on migrant youth.

Intercultural competence has been one of the key concepts in migration related studies. Many researchers agree that intercultural competence is the capability to deal with cultural foreignness and to successfully communicate and interact with people of different languages and cultures (see e.g. Roth 1996; Luchtenberg 1999). In the context of the interculturality in a migration society, this normalised understanding of intercultural competence, however, is problematic because it neglects the culture-based power relationships between major groups and migrant minorities. Following Mecheril’s (2002, 22) critique, culture should be conceived and considered as social practice rather than just the valid meaning system only for the majority groups. Therefore, intercultural competences cannot separate from the “particular meaning of context-specific culture-practice” (Mecheril 2002, 27). Or in other words, to understand intercultural competences, we need to above all reflect on who falls back on culture under what conditions and with which consequences.

In this theoretical framework, intercultural competences, from the perspective of migrant youth with the aim of promoting their equal social cultural status, then have to involve at least three aspects: the culture of majorities as well as the culture of their own ethnic groups and the cultural relationships in between.

Miller (1995) argues that to be a citizen in a migration society is to share in a common identity, but at the same time to have a powerful sense of the cultural distinctness of the group to which one belongs. This argument critically portrays two essential aspects of intercultural competences as formulated in this research. The first aspect concerns capabilities for migrant youth to actively integrate into the hosting ethnic society. This has been a dominant strategy of migration policies. The second dimension, which has been much neglected, refers to capabilities for migrant youth to know, to value and to develop their own ethnicity and culture. With both aspects, migrant young citizens are capable of reflectively constructing a(n) (intercultural) self-identity with sharing in a common social cultural consciousness with the major groups and at the same time with a powerful sense of cultural distinctness of the group which they belong to.

Following this argument, the understating of intercultural competences can be further extended regarding its dimensions. Different from many existent studies which more concentrate on different skills for and attitudes toward intercultural communication, intercultural competences are also critical to be comprehended as capabilities of self-reflection in a multicultural life context. In the context of the German Bildung concept, this is exactly one crucial dimension of life competences for young people to realise self-formation and life-formation. Under the primary “Bildung” relationships of self to the factual world, to the social world and to the self world (Meder 2002), intercultural competences can then be structuralised into three dimensions:

-

Self-factual world dimension: intercultural knowledge

-

Self-social world dimension: intercultural social relations

-

Self-self world dimension: intercultural self-identity

Particularly from the perspective of migrant youth and with an equal consideration of migrant culture, on the first dimension, intercultural competences refer to capabilities for migrant youth to consciously acquire both the mainstream cultural knowledge of the hosting nation and their own ethnic cultural knowledge.

Under the relation of self to the social world or the society, intercultural competences mean on the one hand being able to actively interact with and integrate into the mainstream society and construct intercultural social relations with ethnic majorities and other ethnic groups; and on the other hand also being able to maintain and construct social relationships with their own ethnic groups.

On the third dimension of self-self relation, intercultural competences refer to capabilities to reflectively construct self-identity based on a common social cultural consciousness shared with the ethnic majorities and other ethnic groups as well as on valuing their own ethnicity and culture.

2.2 Online socio-cultural networks and acquisition of intercultural competences

Based on the above understanding of intercultural competences from the perspective of migrant youth, it is clear that the development of intercultural competences requires intercultural interaction of migrant young people with peers of different social, cultural and ethnic characters, in which socio-cultural networks as social support will form and then further affect different styles of intercultural interaction.

As formulated by Norris (2003), in the space of online interaction, there are bonding and bridging structures. Bridging structure refers to socio-cultural networks that bring together people of different social, cultural and ethnic background, and bonding network brings together people of homogeneous social, cultural and ethnic characteristics. Both networks, according to Bourdieu (1990), are supposed to function as different resources of ethnic, cultural, linguistic habitus as well as support. As a group of similar sorts, online bonding networks can raise the tendency toward cultural distance and segmentation from other culture and ethnicities of the multicultural society. Consequently, they are more likely to help develop competences concerning one’s own ethnicity and cultural but at the same time to restrict intercultural and inter-ethnical dialogue. In contrast, online bridging networks as a structure of heterogeneous social cultural characteristics are more likely to enable reconstruction of socio-cultural networks in online society, for example, through connecting migrant youth with native peers. They therefore are more likely to foster intercultural interaction and intercultural competences.

Based on this theoretical approach, the perspective of socio-cultural networks is employed in this research as the main indicator to analyse intercultural competences fostered by Internet. Two main questions are then posed: whether bonding and bridging socio-cultural networks also exist among the migrant youth when they use Internet and which types of online groups they belong to; secondly, what differences in fostering intercultural competences there are among different online networked groups or how these networks influence their intercultural competences development.

3 Operationalisation of an empirical research [4]

Due to the special socio-cultural background and the disadvantaged educational situations of the migrant youth with Turkish migration background in Germany, they are chosen as empirical sample in this empirical research.

While Turkish migrant youth constitute the largest proportion [5] of the school students from immigrated families in Germany, they perpetually belong to the most disadvantaged groups in German educational system, often the case holding lower level of competences acquisition. Additionally, the youngsters from the immigrated Turkish families in Germany hold a distinctive socio-cultural background which maintains a strong bonding character. Studies from e.g. Nauck and Kohlmann (1999) indicate the Turkish ethnicity and culture plays a dominant role in the socio-cultural life of the Turkish immigrant families. This typical bonding socio-cultural structure in the daily life context of Turkish migrant youth enables this group a good sample to be involved to explore the roles of Internet in transforming their socio-cultural networks (from offline to online) and in fostering their intercultural competences.

Altogether 324 Turkish youth from Bielefeld city and other three neighbour cities [6] voluntarily participated in the questionnaire survey at 26 youth centres and Internet cafes. Final valid cases for analysis are 300. The whole questionnaire survey was carried out with interview-administered method.

4 Preliminary findings of an empirical research on the role of Internet in fostering intercultural competences of migrant youth: youngsters with Turkish migration background in Germany as empirical sample

4.1 Review of contingencies for intercultural competences of Turkish youth fostered by Internet use

According to the structure of intercultural competences discussed in the theoretical approach, the preliminary findings on the role of Internet in fostering development of intercultural competences of Turkish youth will be discussed in three dimensions respectively.

4.1.1 Dimension of intercultural knowledge

Firstly, concerning the knowledge dimension of intercultural competences, language knowledge plays a crucial role in intercultural dialogue and especially for social integration of migrant youth. In the questionnaire there is a question asking the Turkish youth which language they mostly use to chat, German, Turkish or both?

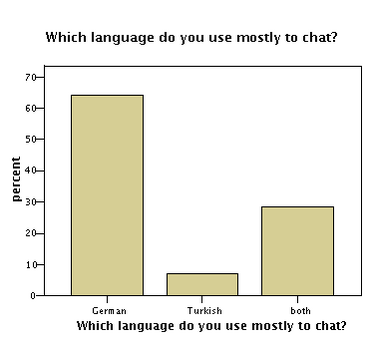

Figure 1: Frequency of using German, Turkish or both languages to chat

As shown in the above figure, more than 60% of them chat mostly in German. In comparison, the rate of chatting in both German and Turkish is 30%. Only 7% of them chat mainly in Turkish. This indicates that using Internet does provide possibilities for Turkish youth to practise and improve their Turkish and especially German language.

Base on this, it is more interesting to see what motivations the Turkish youth have in choosing German or Turkish language to chat. As shown in the following table 1, in answering why they chat in German, about 40% of them agreed that chatting in German helped them to improve their German language. Only 22, 6% of them said chatting in German helped them to widen their knowledge about Germany.

Table 1: Frequency of different reasons for using German to chat

|

Why do you use German to chat? |

Yes (%) |

No (%) |

|

It helps me to improve my German. |

40,2 |

59,8 |

|

It helps me to widen my knowledge about Germany. |

22,6 |

77,4 |

As shown in table 2, in answering why they chat in Turkish, about 37% of them agreed that chatting in Turkish helped them to improve their Turkish language. And 28% of them agreed that chatting in Turkish helped them to widen their knowledge about Turkey.

Table 2: Frequency of different reasons for using Turkish to chat

|

Why do you use Turkish to chat? |

Yes (%) |

No (%) |

|

It helps me to improve my Turkish. |

37 |

63 |

|

It helps me to widen my knowledge about Turkey. |

28 |

72 |

These frequency data indicate that although using Internet provides contingencies for Turkish youth to improve their intercultural knowledge about both German and Turkish languages as well as both countries, the percentage of the Turkish youth being able to employ and realise these possibilities is not so high.

4.1.2 Dimension of intercultural social relations: online socio-cultural networks of Turkish migrant youth

Based on the research hypotheses of online bonding and bridging socio-cultural networks in virtual interaction space, it is interesting to see how Internet fosters online socio-cultural networks among Turkish youth when they use Internet.

There is a relevant question asking the Turkish youth what has changed to their friend cycle since they started to use Internet. Answers are shown in table 3.

Table 3: Factors to formulate bonding and bridging socio-cultural networks

|

Since I started to use Internet, I have more … |

|

|

Turkish friends |

international friends |

|

friends who have same religionary belief |

friends who have different religionary belief |

|

friends who have similar hobbies |

friends who have different hobbies |

|

Bonding factor |

Bridging factor |

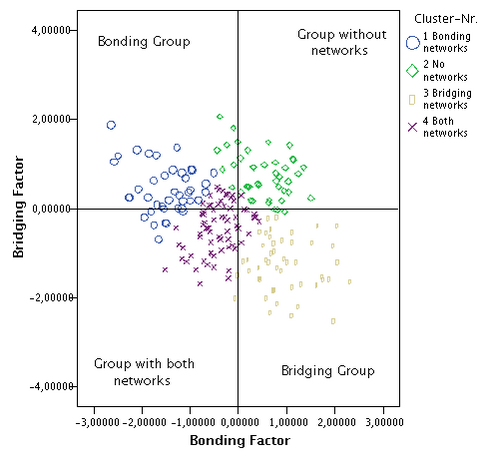

From the six questions, bonding and bridging factors are firstly extracted out with principal factor analysis. Based on the two factors, four groups are formulated according to cluster analysis by SPSS. They are bonding groups, bridging groups, the groups connected with both bonding and bridging networks, and the groups without any networks. This online typology is displayed in the following figure 2.

Figure 2: Typology of online socio-cultural groups

This figure clearly displays that both bonding and bridging networks exist among Turkish youth when they go online. It indicates the Internet not only helps the Turkish youth to extend their Turkish networks based on Turkish ethnicity and culture, but also functions to diversify their networks with peers of different social, cultural and ethnic background. Or in other words, Internet does have contingencies to foster the Turkish migrant youth to construct their intercultural social relations.

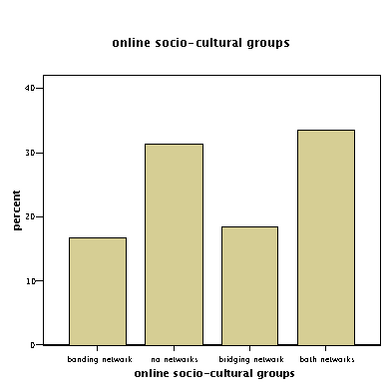

As shown in the following figure 3 of frequency of connection with different online socio-cultural networks, about 16, 7% of the Turkish youth have bonding networks which means they have more friends with same ethnic and religious background on the Internet. And about 18, 4% of them are connected with bridging networks or with more German and other international friends in virtual space. In comparison, about twice more (33, 4%) of the Turkish youth respondents belong to both bonding and bridging networks when they use Internet. But still there are 31, 4% left who are not connected with any networks. This indicates that there are still quite a few Turkish youth who are not capable of constructing intercultural social relations through employing the possibilities provided by Internet.

Figure 3: Frequency of different online socio-cultural groups

Going further from constructing social bonds with different ethnic peers, the social dimension of intercultural competences also refers to the competences for migrant youth to employ their intercultural social relations, both offline and online, to solve problems. In this survey, there is a question concerning how often they turn to different ethnic people, offline and online, for help when they have a problem for example with using Internet. About half (48%) of them said they often asked Turkish people from their acquaintance circle for help. 56% of them often turned to German and other ethnic people in their life for help. In comparison, only 15% of them often turned to Turkish people whom they got to know from Internet for help. And 16% of them often asked German and other people they got to know from Internet for help. This indicates that online intercultural social bonds are still not so often employed as offline social bonds by Turkish migrant youth in looking for social support.

In summary, on the one hand, important contingencies are opened in virtual space for Turkish youth to develop their intercultural competences, for instance, improving their intercultural knowledge about both hosting country and their own culture and widening their social support through diversifying their intercultural socio-cultural networks. However, on the other hand, these contingences are still not well realised or employed by all Turkish youth in their engagement with Internet. It is then critical to find possible indicators to interpret the deficiencies and the differences.

4.2 Differences in intercultural competences under online socio-cultural structure

According to the theoretical approach of socio-cultural networks, online bonding and bridging networks as different ethnic, social and culture support are important factors to influence migrant youth on development of intercultural competences. Starting from this hypothesis, intercultural competences of the Turkish migrant youth are going to be compared from the three dimensions among the four different network groups as formulated in figure 2 – bonding group, bridging group, group with both bonding and bridging networks, and group without any networks.

4.2.1 Differences in developing intercultural knowledge

Concerning using Internet to develop their intercultural knowledge, differences are found out among the four socio-cultural networked groups. Firstly, the correlation analysis as shown in table 4 displays a significant association of bridging networks with agreement on that chatting in German helps them to better off their German as well as to widen their knowledge about Germany. In contrast, there is no correlation between bonding networks and these agreements.

Table 4: Pearson correlation between bonding/bridging network and “why do you mainly use German to chat?”

|

Why do you mainly use German to chat? |

Bonding factor |

Bridging factor |

|

It helps to better off my German |

-,033 |

-,145(*) |

|

It helps to widen my knowledge about Germany |

-,023 |

-,189(**) |

** Correlation is significant at the level of 0, 01 (2-tailed).

* Correlation is significant at the level of 0, 05 (2-tailed).

This difference can be further confirmed by, for example, the means analysis as displayed in table 5. The Turkish youth from bridging networks agreed more than those from bonding networks that chatting in German helped them to widen their knowledge about Germany. In contrast, the group of bonding networks agreed more than those from bridging networks that chatting in Turkish helped them to widen their knowledge about Turkey. In addition, if we compare the group connected with both bonding and bridging networks with bonding and bridging group respectively, it is clear to see those from the “both” group hold a much higher agreement than the other groups on that chatting in German helps them to widen their knowledge about Germany and chatting in Turkish helps them to widen their knowledge about Turkey.

Table 5: Means analysis of agreement on that chatting in German/Turkish helps them improve their knowledge about Germany/Turkey among the four online socio-cultural networked groups

|

Cluster-Nr. |

Chatting in German helps me to widen my knowledge about Germany Means |

Chatting in Turkish helps me to widen my knowledge about Turkey Means |

|

both networks |

,3118 |

,3889 |

|

bridging networks |

,2308 |

,1667 |

|

bonding networks |

,1892 |

,3600 |

|

no networks |

,1463 |

,1250 |

(Notice: high value means more agreement – yes: 1; no: 0)

Both findings above regarding differences in intercultural knowledge of the Turkish youth among the four groups indicate that bonding networks play an obvious role in improving their own cultural knowledge, while bridging networks play a significant role in bettering off their knowledge about German culture. However, to acquire a critical intercultural knowledge involving both aspects, a combination of bonding and bridging networks is proved to be more necessary.

4.2.2 Differences in developing intercultural social relations

Regarding the dimension of intercultural social relations, bonding and bridging networks play an even more significant role. As the analysis of correlation between strategies of solving problems and bonding/bridging networks (table 6), bonding networks are more significantly correlated with turning to Turkish people, both online and offline, for help. In comparison, bridging networks are more significantly associated with asking German and other ethnic persons, both online and offline, for help with solving problems.

Table 6: Pearson correlation analysis between bonding/bridging networks and frequency of turning to Turkish/German people for help with problem

|

When you have a problem with using Internet, how often do you turn to … for help |

Bridging Factor |

Bonding Factor |

|

Turkish people from your acquaintance circle |

-,002 |

,295(**) |

|

|

,972 |

,000 |

|

Turkish people you got to know on the Internet |

,188(**) |

,434(**) |

|

|

,001 |

,000 |

|

German and other people you know in your life |

,264(**) |

,092 |

|

|

,000 |

,116 |

|

German and other people you got to know on the Internet |

,367(**) |

,201(**) |

|

|

,000 |

,001 |

** The correlation is significant at the level of 0, 01 (2-tailed).

In addition, as the means analysis in the following table 7 shows, it is more interesting to see the tendency again that the groups connected with both bonding and bridging networks acquire relative high value in all the strategies of solving problems through turning to both Turkish and German people for help. This indicates that this group employ intercultural social bonds for support to solve problem more often than the other network groups.

Table 7: Means analysis of how often the Turkish youth turn to Turkish/German people for help with problem among the four online socio-cultural groups

|

When you have a problem with using Internet, how often do you turn to…for help? Cluster-Nr. |

|

Turkish people from your acquaintance circle |

Turkish people you got to know on the Internet |

German and other people you know in your life |

German and other persons you got to know on the Internet |

|

bonding network |

Means |

2,2857 |

3,0612 |

2,6122 |

3,3878 |

|

no networks |

Means |

2,7391 |

3,7826 |

2,7826 |

3,7609 |

|

bridging network |

Means |

2,9630 |

3,6481 |

2,2593 |

3,2407 |

|

both networks |

Means |

2,4184 |

3,0612 |

2,3265 |

3,0104 |

(Notice: low value stands for high frequency – from very often: 1 to never: 4)

4.2.3 Differences in developing intercultural-identity

Finally, let us come to the identity dimension of intercultural competences. Concerning this aspect there is no direct question in this empirical research. Actually, because identity construction is a complicated continuing process especially for young people, it is quite difficult to directly find out how much the self-identity reported by Turkish youth is influenced by using Internet in the multicultural virtual context. To clarify this, qualitative interviews are needed to explore deeper. However, it is still interesting to see how the Turkish youth regard themselves concerning ethnic identity and what differences exist among different socio-cultural networks.

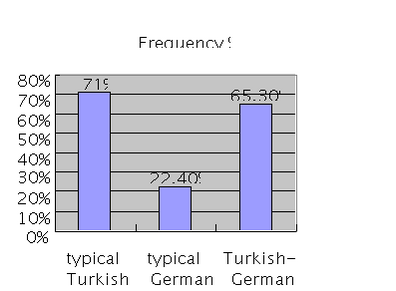

In this survey there is a question asking Turkish youth respondents about how much they agree that they regard themselves as typical Turkish, typical German and Turkish-German respectively.

As displayed in the following figure 4, the majority of them, about 71%, agreed that they regarded themselves as typical Turkish, 22, 4% as typical German, and 65,3% as Turkish-German.

Figure 4: Frequency of three ethnic self-identities among Turkish migrant youth

The correlation analysis in table 8 further displays that bonding networks are more significantly correlated with Turkish identity and that in comparison bridging networks are more significantly related with Turkish-German identity and German identity.

Table 8: Pearson correlation analysis between bonding/bridging networks and different self-identity

|

How much do you agree that you regard yourself |

Bridging Factor |

Bonding Factor |

|

as typical Turkish |

-,113 |

,143(*) |

|

as typical German |

,152(**) |

-,025 |

|

as Turkish-German |

,133(*) |

-,068 |

* The correlation is significant at the level of 0, 05 (2-tailed).

** The correlation is significant at the level of 0, 01 (2-tailed).

Besides, it is more interesting to see here, as the figure 5 of the means values on Turkish-German identity shows, the bridging network group and the group connected with both bonding and bridging networks more agree on the hybrid or intercultural identity as Turkish-German.

Figure 5: Means value of Turkish-German identity among the four online socio-cultural networks

(Notice: lower value means more agreement – 1: completely agree; 2: rather agree; 3: rather disagree; 4: completely disagree)

Although we cannot yet accordingly decide the causal relations between identity construction of Turkish youth and their online socio-cultural networks, the correlation results do indicate the contingency of online socio-cultural networks for Turkish youth to construct and reconstruct their (intercultural-)identity in the intercultural context.

5 Conclusions, problems and implications for youth work

Based on the analyses of the three dimensions of intercultural competences of Turkish migrant youth influenced by using Internet mainly under the indications of online socio-cultural networks, now in the end, we come to conclusions, problems and implications for youth work in brief.

First, Internet does provide contingencies for Turkish migrant youth to develop intercultural competences not only for integration into German society but also for understanding and developing their own ethnic culture through improving their intercultural knowledge and constructing intercultural social bonds. This provides potential, at least from the perspective of migrant culture, to enhance intercultural dialogue and to break the unequal power relationships especially in the informal life context.

Secondly, both bonding and bridging socio-cultural networks in virtual space are important indicators in fostering the development of intercultural competences of Turkish migrant youth. But they play different roles. Bonding networks are more significant on the aspect of their own cultural competences. In comparison, bridging networks are more correlated with the development of their German cultural competences or competences for social integration.

A tendency is displayed that to be more powerful in developing intercultural competences of both aspects, it is necessary for migrant youth to be connected with both bonding and bridging networks.

Thirdly, problems are also clear. As shown by the preliminary findings, the contingencies of Internet in fostering intercultural competences, as discussed above, are still not much employed and realised by Turkish youth. There could be different reasons to explain this. In this research it can be firstly interpreted that many Turkish migrant young people still lack recognition and capabilities to construct or reconstruct their socio-cultural networks or relations through using Internet and further to employ the relations as social support or social capital in their life context. This in itself is already an essential part of intercultural competences.

Therefore, finally, one important implication for youth work practice is plain to see: to enable migrant youth to develop intercultural competences through using Internet, it is necessary for youth work to help them recognize, construct, as well as employ both bonding and bridging networks. Especially for those disadvantaged migrant youth, for instance, the Turkish migrant youth who are much bonded within their own ethnicity as well as socio-cultural networks in the daily life context and still segregated from other culture like the hosting German culture, it is important for youth work to bridge their contacts with peers of different social cultural characters or reconstruct their offline socio-cultural networks through developing online contingencies of intercultural interaction. For practice of youth work, different projects focused on “Internet use and construction of socio-cultural networks” are worth carrying out, especially with participation of the migrant youth.

In the field of migrant policies, the point of fostering the construction of migrant youth’s intercultural social networks, online as well as offline, with the aim to widen their intercultural social support, however, has been much neglected so far. Reviewing the existent policies to support migrant youth especially to foster their competences development in both formal and non-formal educational contexts, many of them are mainly focused on language support (see e.g. Gogolin, Neumann and Roth 2003; Stanat and Christensen 2006) and oriented only by the dominant formal educational standards which however are still unequally normalised by the mainstream German culture. Despite that the migrant youth are well assimilated by German language and culture, this support is still far from enough since they are still structurally disadvantaged in the respect of socio-cultural networks as well as intercultural social support. The unequal power relationships are not changed. Consequently, for migration policy making, how to foster intercultural social support for migrant youth through Internet is a radical implication needed to be concerned.

Putting the discussion again in the context of migration society, it is still necessary to argue that to foster intercultural competences is not just for competences development itself. Let us return to the critical reflection on the meaning of intercultural competences at the beginning of the text. The most significant target to foster intercultural competences of migrant youth through Internet is eventually to reduce the perpetuating social and educational inequalities the migrant youth have been experiencing in the migration society. All efforts, no matter in political or social work fields, are necessarily targeted to improve the social inequality as well as social justice in an ever-increasing multicultural society for migrant minorities. This critical and reflective interculturality therefore constitutes a must for both professionality of social work and capability of migration policies.

6 Further discussions

Based on this empirical research, some new research questions are further raised. Firstly, as mentioned before, intercultural competences are crucial for both migrant youth and native youth in a migration society. Therefore, further research is necessary to explore the role of Internet in fostering intercultural competences of native (e.g. German) youth and especially to compare and explain the differences between migrant youth and native peers in the same contexts.

Secondly, to deepen the understanding about the processes and contents of intercultural dialogue especially between youth with different ethnic and cultural background when they use Internet, for example, what and how they interchange with each other in virtual space, how their intercultural competences develop in the processes, and how they evaluate that etc., qualitative researches are needed to deepen in the following new research.

7 Appendix: Questions related with intercultural competences of Turkish youth from the questionnaire survey

Intercultural knowledge:

Q30. Which language (Turkish or German or both) go you use mostly to chat?

Q31. Why do you use German to chat?

31-1. it helps me to better off my German (e.g. speaking, writing, grammar etc.)

31-2. it helps me to widen my knowledge about Germany

31-5. most people with whom I chat speak German

Q32. Why do you use Turkish to chat?

32-1. it helps me to better off my Turkish

32-2. it helps me to widen my knowledge about Turkey

32-5. most of people with whom I chat speak Turkish

Intercultural social relations:

Q37. Imagine that you have a problem with using Internet and need help. How often do you turn to … for help?

37-1. Turkish people from your acquaintance circle

37-2. Turkish who you got to know on the Internet

37-3. German and others who you know

37-4. German and others who you got to know from the Internet

Q39. What has changed for you since you used Internet?

39-1. I have more friends from other countries

39-2. I have more Turkish friends

39-5. I have more friends with different interests and hobbies

39-6. I have more friends with same interests and hobbies

39-7. I have more friends who have different believes like me

39-8. I have more friends who have same believes like me

Intercultural self-identity:

Q06. Would you agree to the statements?

06-1. I regard myself as typical Turkish

06-2. I regard myself as typical German

06-3. I regard myself as Turkish-German

[1] “Bildung” is a typical and also classical concept in German educational context. There is actually no exact and precise equivalent of Bildung in other languages, but it basically means e.g. “self-education” (Gadamer 1979) or “self-formation or self-cultivation” (Sorkin 1983; Lǿvlie 2003). Generally, in English context, Bildung is also understood as and translated into education.

[2] In Web 2.0 time, one of the characters is the transformation from the classical online communities to social networking. This means that the social relationships or networks of users are not anymore limited inside some community or a certain communities but much already beyond the communities. Therefore in this research, the focus is on social networks online rather than the classical online communities.

[3] KIB: Kompetenzzentrum Informelle Bildung (competence centre of informal education). See also: Otto, Hans-Uwe and Kutscher, Nadia (eds.) (2004); Otto, Hans-Uwe/ Kutscher, Nadia/ Klein, Alexandra/ Iske, Stefan (2004); Otto, Hans-Uwe/ Kutscher, Nadia/ Klein, Alexandra/ Iske, Stefan (2005); Iske, Stefan/ Klein, Alexandra/ Kutscher, Nadia (2005).

[4] The empirical research is based on my dissertation project on “Informal Learning of Migrant Youth in Online Socio-cultural Networks”, in which it is surveyed how migrant youth (young people with Turkish migration background as empirical sample) learn informally and develop their life competences through using Internet as an informal Bildung process, and also analyzed how different socio-cultural networks in virtual space as different social cultural capital influence migrant youth on using Internet and developing life competences. This report with the preliminary findings on the role of Internet in fostering intercultural competences is therefore a part of this whole research.

[5] The statistics provided by “Statistical Publications of Conference of Minister of Education” (Statistische Veröffentlichungen der Kultusministerkonferenz) in October 2002 showed that from 1991 to 2000 the students whose origin country was Turkey reached almost 502,000 in 2000, which amounted to 43, 4% in the whole population of the foreign school students in Germany. This largest proportion still maintains currently with a rate of about 43, 1% from 2004 to 2006 as shown by the statistics from the “German federal statistics office” (Statistisches Bundesamt Deutschland). See http://www.destatis.de/

[6] The other three cities are Herford, Gütersloh and Dortmund respectively.

References

Bonfadelli, H. 2002: The Internet and Knowledge Gaps – a theoretical and empirical investigation, in: European Journal of Communication, Vol. 1, pp. 65-84.

Bonfadelli, H. and Bucher, P. 2007: Alte und neue Medien im Leben von Jugendlichen mit Migrationshintergrund, in: Otto, H.-U., Kutscher, N., Klein, A. and Iske, S. (Kompetenzzentrum Informelle Bildung) (eds.): Grenzenlose Cyberwelt? Zum Verhältnis von digitaler Ungleichheit und neuen Bildungszugängen für Jugendliche. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Bourdieu, P. 1983: The Forms of Capital, in: Richardson, J. G. (eds.): Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education. Connecticut: Greenwood Press, pp. 241-258.

Bourdieu, P. and Passeron, J. 1990: Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture. London: Sage Publications.

Castro Varela, M. d. M. 2002: Interkulturelle Kompetenz – ein Diskurs in der Krise, in: Auernheimer, G. (ed.): Interkulturelle Kompetenz und pädagogische Professionalität. Opladen: Leske + Budrich, pp. 35-48.

DiMaggio, P. and Hargittai, E. 2001: From the ‘Digital Divide’ to ‘Digital Inequality’: Studying Internet Use As Penetration Increases. Available online 20.12.2007 < http://www.webuse.umd.edu/webshop/resources/Dimaggio_Digital_Divide.pdf >

Gogolin, I., Neumann, U. and Roth, H.-J. 2003: Förderung von Kindern und Jugendlichen mit Migrationshintergrund. Im Auftrag der BLK (Bund-Länder-Kommission). Heft 107. Bonn: BLK.

Hamburger, F. 2006: Konzept oder Konfusion? Anmerkungen zur Kulturalisierung der Sozialpädagogik, in: Otto, H.-U. and Schrödter, M. (eds.): Soziale Arbeit in der Migrationsgesellschaft. Multikulturalismus – Neo-Assimilation – Transnationalität. Lahnstein: Verlag neue Praxis (Zeitschrift für Sozialarbeit, Sozialpädagogik und Sozialpolitik), pp. 178–192.

Jörissen, B. and Marotzki, W. 2007: Neue Bildungskulturen im ‚Web 2.0’: Artikulation, Partizipation, Syndikation, in: von Gross, F., Marotzki, W. and Sander, U. (eds.): Internet – Bildung – Gemeinschaft, Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, pp. 203-225.

Kirby, R. 2001: Conversation in Cyberspace: informal education and new technology, in: Research in Post-Compulsory Education, 3, pp. 277-284.

Livingstone, S., Bober, M. and Helsper, E. 2004: Active participation or just more information? Young people's take up of opportunities to act and interact on the internet. Project Report, London School of Economics and Political Science, London, UK. Available online 20.12.2007 < http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/396/01/UKCGOparticipation.pdf >

May, S. 1999: Critical Multiculturalism and Cultural Difference: Avoiding Essentialism, in: May, S. (ed.): Critical Multiculturalism: Rethinking Multicultural and Antiracist Education. London: Falmer Press, pp. 11-41.

Mecheril, P. 2001: Was ist interkulturelle Kompetenz? Pädagogischer Bedarf, begriffliche Unklarheit und technologische Suggestion. Habilitationsvortrag. University Bielefeld, Faculty for Educational Science, Bielefeld, Germany.

Mecheril, P. 2002: „Kompetenzlosigkeitskompetenz“. Pädagogisches Handeln unter Einwanderungsbedingungen, in: Auernheimer, G. (ed.): Interkulturelle Kompetenz und pädagogische Professionalität. Opladen: Leske+Budrich, pp. 15-34.

Mecheril, P. 2003: Behauptete Normalität – Vereinfachung als Modus der Thematisierung von Interkulturalität, in: Erwägen, Wissen, Ethik, 1, pp. 198-201.

Meder, N. 2002: Nicht informelles Lernen, sondern informelle Bildung ist das gesellschaftliche Problem, in: Fromme, J. and Meder, M. (eds.): Spektrum Freizeit (Halbjahreschrift Freizeitwisschenschaft), 1, Bielefeld: Janus Verlaggesellschaft, pp. 8-17.

Mesch, G. S. 2007: Social Diversification: A Perspective fort he Study of Social Networks of Adolescents Offline and Online, in. Otto, H.-U., Kutscher, N., Klein, A. and Iske, S. (Kompetenzzentrum Informelle Bildung) (eds.): Grenzenlose Cyberwelt? Zum Verhältnis von digitaler Ungleichheit und neuen Bildungszugängen für Jugendliche. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, pp. 105-117.

Miller, D. 1995: Reflection on British national identity, in: New Community, 21, pp. 153-166.

Nauck, B. and Kohlmann, A. 1999: Kinship as Social Capital: Network Relationships in Turkish Migrant Families, in: Richter, R. and Supper, S. (eds.): New Qualities in the Lifecourse. Intercultural Aspects. Würzburg: ERGON Verlag, pp. 199-218.

Norris, P. 2003: The bridging and bonding role of online communities, in: Philip, H. and Jones, S. (eds.): Society Online – the Internet in context. London: Sage, pp.3-13.

Roth, K. 1996: Erzählen und Interkulturelle Kommunikation, in: Roth, K. (ed.): Mit der Differenz leben. Europäische Ethnologie und Interkulturelle Kommunikation. Münster: Waxmann, S. 63-78.

Schulte, J. 2003: Die Internet-Nutzung von Deutsch-Türken, in: Becker, J. and Behnisch, R. (eds.): Zwischen kultureller Zersplitterung und virtueller Identität – Türkische Medienkultur in Deutschland. Rehburg-Loccum: Evangelische Akademie Loccum, pp. 115–123.

Senay, U. 2003: Virtuelle Welten für Migranten im World Wide Web, in: Becker, J. and Behnisch, R. (eds.): Zwischen kultureller Zersplitterung und virtueller Identität – Türkische Medienkultur in Deutschland. Rehburg-Loccum: Evangelische Akademie Loccum, pp. 125-134.

Short, G. and Carrington, B. 1999: Children’s Construction of Their National Identity: Implications for Critical Multiculturalism, in May, S. (ed.): Critical Multiculturalism: Rethinking Multicultural and Antiracist Education. London: Falmer Press, pp. 172-190.

Sørensen, B. H., Danielsen, O. and Nielsen, J. 2007: Children's informal learning in the context of school of knowledge society, in: Education and Information Technologies, 1, pp. 17-27.

Stanat, P. and Christensen, G. 2006: Schulerfolg von Jugendlichen mit Migrationshintergrund im internationalen Vergleich. Eine Analyse von Voraussetzungen und Erträgen schulischen Lernens im Rahmen von PISA 2003. Berlin: BMBF.

Thomas, A. 2003: Interkulturelle Kompetenz – Grundlagen, Probleme und Konzepte, in: Erwägen, Wissen, Ethik, 1, pp. 137-150

Wellman, B., Salaff, J., Dimitrova, D., Garton, L., Gulia, M., Haythornthwaite, C. 1996: COMPUTER NETWORKS AS SOCIAL NETWORKS: Collaborative Work, Telework, and Virtual Community, in: Annual Review of Sociology, 22, pp. 213-38.

Wellman, B. and Gulia, M. 1999: Net surfers don't ride alone: virtual communities as communities, in: Kollock, P. and Smith, M. (eds.): Communities and Cyberspace. New York: Routledge. Available online 20.12.2007 < http://www.chass.utoronto.ca/~wellman/publications/netsurfers/netsurfers.pdf >

Wellman, B. and Hampton, K. 1999: Living Networked On and Offline, in: Contemporary Sociology, 6, pp. 648-654. Available online 20.12.2007 < http://www.socialdata.org/pdf/Misc/WellmanNetworkOnOffline.pdf >

Züchner, K. 2003: Interkulturelle Kompetenz und Technologiedefizit. Eine qualitative Studie zum Prozess der Vorbereitung von zukünftigen Auslandsmitarbeitern auf professionelles handeln. Diplomarbeit. University of Bielefeld, Faculty for Educational Science, Bielefeld, Germany.

Author´s Address:

Yafang Wang

University of Bielefeld

Faculty of Educational Science, Center of Social Service Studies

Postfach 100131

33501 Bielefeld

Germany

Email: yafang.wang@uni-bielefeld.de

urn:nbn:de:0009-0-15559