Empowering Voices, Bridging Worlds: The Potential of Photovoice for Empowerment, Reflection, and Connection in Diverse Societies

Carmen S. Lienen, FernUniversität in Hagen

Andrea Monika Frisch, FernUniversität in Hagen

Agostino Mazziotta, FH Münster – University of Applied Sciences

Anette Rohmann, FernUniversität in Hagen

1 Introduction

The meaning of diversity for social work has historically changed with the understanding of the profession’s mission. While early social work more closely resembled a containment of diversity and an assimilation of people to the norms and system of the majority society (Baylor School of Social Work Team, 2022), the field became more sensitive towards and supportive of diversity in the second half of the 20th century (Grunwald & Thiersch, 2009). In Germany, for example, deficit-oriented practices primarily aimed at assimilating migrants were increasingly replaced by resource-oriented, intercultural pedagogy (Perko & Czollek, 2022), with some adopting more critical diversity approaches that focus on people’s complex lived realities - or ‘lifeworlds’ (Thiersch, 1978). These lifeworlds are marked by different identities, values, and contexts. In the present article, we approach diversity through the lens of intersectionality, a framework that acknowledges the complex interweaving of different identities and systems of oppression (Crenshaw, 1989).

The objective of this article is to introduce photovoice, a community-based participatory action research method, as a methodological tool that has the potential to cultivate diversity sensitivity within social work. Leveraging photographs and narratives, we believe that photovoice is particularly well suited to a) providing in-depth insights into clients’ (and providers’) complex lifeworlds, b) facilitating critical reflections on the role as social workers, and c) fostering an empathetic and informed relationship between social work providers and their clients.

In the first part of the article, we describe our understanding of diversity through the framework of intersectionality (Crenshaw, 1989) and explore photovoice methodology (Wang & Burris, 1997). The second part of the article brings these two elements together by providing a nuanced discussion of how photovoice can benefit diversity in social work. Specifically, we analyze how photovoice can serve the triple-mandate of social work through the method’s orientation along empowerment and social justice. We then extend the focus to how photovoice can be employed to support a diversity-sensitive relationship between providers and clients of social work. We acknowledge and critically reflect on the limitations of this method and potential challenges of the implementation of photovoice in diverse societies. The present article is intended to motivate and empower social workers to use photovoice in their work. We therefore conclude the article by providing practical recommendations.

2 Understanding diversity through an intersectional lens

We live in increasingly diverse societies. In Germany, for example, more than a third of people under the age of 18 have a migratory background (Petschel, 2021, data from 2019). Diversity, of course, goes beyond ethno-cultural heterogeneity. It also encompasses aspects such as age, gender, class, disability, cultural and religious background, neurodiversity or sexual identity - which can be more or less visible characteristics of a person (Aschenbrenner-Wellmann & Geldner, 2021). These different characteristics influence a person’s lived experiences, their access to resources and to potentials of social and political participation.

In the present article, we reflect on diversity from an intersectional perspective. One of the first comprehensive descriptions of the concept of intersectionality dates back to 1977 and was formulated by the Combahee River Collective, a group of Black lesbian feminists. The Collective argued that both the women’s movement and the anti-racist civil rights movement failed to adequately consider the specific needs of Black lesbian women. While the women’s movement primarily represented the interests of White women, the anti-racist civil rights movement focused mainly on the interests of Black men. Consequently, the multiple discrimination of Black women through racism and patriarchal structures or sexism was not sufficiently recognized. Therefore, the Collective saw the need to advocate for themselves and called for a policy that considers the interweaving of various dimensions of diversity:

“The most general statement of our politics at the present time would be that we are actively committed to struggling against racial, sexual, heterosexual, and class oppression, and see as our particular task the development of integrated analysis and practice based upon the fact that the major systems of oppression are interlocking” (Combahee River Collective, 1977, n. p.).

The term intersectionality was coined in 1989 by the legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw in her article “Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics.” Crenshaw argued that an analysis focusing solely on one dimension of diversity like gender or ethnicity is insufficient. Such a view neglects the complexity of real situations and overlooks the experiences of people affected by multiple stigmatized dimensions of diversity, such as Black women or working-class gay men. Crenshaw emphasized that the experiences of people who are simultaneously subjected to various forms of discrimination can only be fully captured when the intersections of these various dimensions of diversity are considered:

„Because the intersectional experience is greater than the sum of racism and sexism, any analysis that does not take intersectionality into account cannot sufficiently address the particular manner in which Black women are subordinated.“ (Crenshaw, 1989, p. 140).

The social position of a person does not simply arise from the addition or subtraction of individual discriminations or privileges, but from the complex interactions of the various social categories to which they belong. In contrast to the diversity approach, which often focuses on single dimensions that are either celebrated (e.g., in pride month) or problematized (e.g., in the context of migration), intersectionality focuses explicitly on the intersections of these categories.

The intersectional approach also conducts a critical analysis of the context, structural factors, and the associated dynamics of power, privilege, and inequality (Hudson & Mehrotra, 2021; Müller & Polat, 2022). This is important because discussing diversity only as a descriptive phenomenon runs the risk of seeing differences rather than inequalities. By going beyond a description of differences, the intersectional approach explores interdependencies and, above all, their effects in social power and domination relations (Rein & Riegel, 2016, p. 77). Despite legal measures to protect people with certain diversity characteristics in several countries (e.g., Allgemeines Gleichbehandlungsgesetz [AGG] in Germany), diversity continues to be interlinked with inequality (DiTomaso et al., 2007; DiTomaso, 2021). It thus remains important to reflect on how structures and institutions benefit or fail people based on their intersectional identities.

2.1 Intersectionality and social work

Although the importance of an intersectional perspective is increasingly emphasized in social work, to date concrete understanding and implementation in practice remain limited (Bernard, 2021; Hudson & Mehrotra, 2021; Mattsson, 2014). This has implications for the relationship between service provider and client, as well as the profession’s goals towards social justice.

Concerning the relationship between service providers and clients, one can argue that every interaction between a service provider and a client is a multicultural situation (Lott, 2010). Empirical evidence suggests that ignoring the multicultural dimensions of the interaction, such as different ethnic backgrounds, can negatively affect the working alliance between the client and the service provider. In contrast, proactively addressing these issues can be beneficial for establishing a functional client-provider relationship (Burkard et al., 2015; White-Davis et al., 2016). Research in the field of social work is currently limited regarding the critical importance of explicitly acknowledging cultural dimensions in the relationships between service providers and clients. However, preliminary evidence within the fields of counseling and psychotherapy suggests a significant impact: A meta-analysis encompassing 18 studies found that clients’ perceptions of their therapist’s or counselor’s multicultural competencies positively influence the therapeutic relationship, satisfaction with therapy or counseling, and the effectiveness of concern resolution (Tao et al., 2015). Intersectionality considers the complexity and interweaving of the various cultures to which both the client and the service provider belong and addresses power dynamics in their professional relationship and the broader societal context. By fostering a more holistic and profound understanding of the client’s lifeworld and self-reflexivity (Müller & Polat, 2022), this approach can help build a more authentic relationship between client and service provider.

Similarly, we would argue that an intersectional perspective would benefit the profession’s goals towards social justice. The triple mandate of social work (Staub-Bernasconi, 2018) reflects the idea that social workers not only follow two traditional mandates – helping (first mandate) and controlling (second mandate) – but also a third mandate, which involves participation in social change and the promotion of social justice. This mandate suggests that social workers should play an active role in combating inequalities, discrimination, and social injustice. It recognizes that social problems are not just individual or family challenges, but deeply rooted in societal and structural issues that must be addressed. The International Federation of Social Workers has described social justice as central to their work:

“Social work is a practice-based profession and an academic discipline that promotes social change and development, social cohesion, and the empowerment and liberation of people. Principles of social justice, human rights, collective responsibility and respect for diversities are central to social work. Underpinned by theories of social work, social sciences, humanities and indigenous knowledge, social work engages people and structures to address life challenges and enhance wellbeing” (International Federation of Social Workers, n.d., para. 4).

To do justice to this principle, it is important to consider that people are affected differently by inequality and systems of oppression. Accordingly, social justice may not look the same to all people - a core tenet of the intersectional approach. However, as Jarldorn (2019) citing Williams (1989) points out, “typically, issues of race, gender, and class have been overlooked or marginalized in the discipline of social policy” (Jarldorn, 2019, p. 39). An approach that allows service users to not be the ‘object of social policy’ but agents of change, would be more aligned with the above-stated principles (Jarldorn, 2019).

In the following, we discuss photovoice as one instrument that has the potential to address the complex goals the social work profession has set for itself. In addition to outlining the methodology and its alignment with the stated objectives of social justice, social cohesion, and empowerment, we explore options for integrating photovoice into social work practice.

3 Photovoice—A community-based participatory action research approach

Community Based Participatory Action Research (CBPAR) is an innovative, applied, and collaborative research approach which 1) focuses on the needs, issues, and strategies of a community and their institutions, 2) involves the community in all stages of the research process, and 3) supports strategic measures that facilitate transformation and social change (Israel et al., 2012). CBPAR represents an alternative to more traditional research approaches such as laboratory research or surveys as it focuses on people’s complex, multidimensional, and dynamic experiences in their natural environment (Minkler & Wallerstein, 2003). The strong involvement of participants in the research process (e.g., deciding on the research focus, co-analyzing the data) calls for a particular sensitivity towards ethical standards such as informed consent, confidentiality and the protection of intellectual property, preventing harm and maximizing benefits (Israel et al., 2012).

Photovoice is a research method that was developed by Caroline Wang in the early 1990s at the University of Michigan. The method describes a socio-critical, photo-journalistic approach to social research that was first employed to study health behavior in rural China (Wang et al., 1996). In a photovoice project, members of (often marginalized) groups, use photography and storytelling to identify community struggles and strengths, to facilitate critical consciousness and understanding between community members, and to advocate for social change. Photovoice methodology builds on theories of critical consciousness (Freire, 1970, 1973), documentary photography (Stryker, 1963), and feminist theory (Maguire, 1987), which recognize people as experts of their own reality and thus value their subjective experiences and insider-perspectives as important knowledge (Wang & Burris, 1997). Challenging traditional forms of (participatory) research that often overlooked women’s voices despite claims of being universal, Maguire (1987) introduced a participatory action approach that was informed by intersectional feminist theory. Feminism according to Maguire was based on an acknowledgment of the oppression and discrimination faced by women globally, a commitment to understand the roots and mechanisms of all forms of oppression, “whether based on gender, class, race or culture”, and to engage in individual and collective action to end it (p. 5).

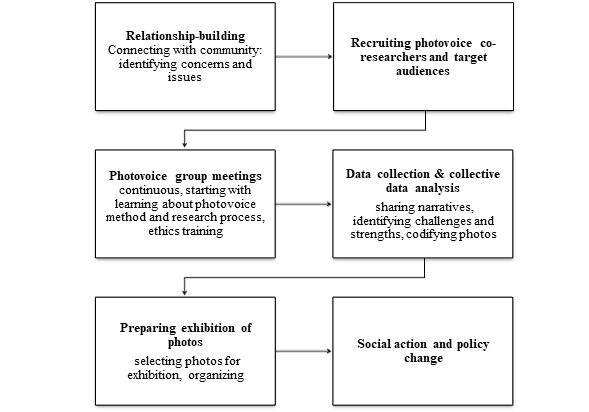

Wang and Burris (1997) built on this approach and combined it with documentary photography. Using photographs as evidence, participants become ‘documenters’ of their own lived experiences (Palibroda et al., 2009; Wang, 1999; Wang & Burris, 1997). A photovoice project starts with an intensive planning phase followed by a workshop in which participants are trained as co-researchers and introduced to the technical, visual, and ethical aspects of photography, e.g. the persuasive, powerful effect of photographs in communication. Afterwards, building on an initial group exchange, participants take photos of their everyday experiences that they then discuss and analyze together with other members of the community to identify areas for action. This critical dialogue is often guided by the so-called SHOWeD questions: “What do you See here?”, “What is really Happening here?”, “How does this relate to Our lives?”, “Why does this condition Exist?” and “What can we Do about it?” (Shaffer, 1983). The results are then publicly disseminated and discussed with potential decision-makers and multipliers, among others, with the aim of improving the situation of the community at micro, meso and macro levels (Wang & Burris, 1997; Wihofszky et al., 2020) (see Figure 1). Research is thus not conducted on the group but together with the group. The acronym VOICE = “voicing our individual and collective experiences” (Wang & Burris, 1997, pp. 380f.) reflects the methodology’s key objective.

Figure 1: Steps of a photovoice project (simplified model)

Note. Steps partly adopted from Palibroda et al. (2019), pp. 27-64.

Adopting participatory research standards, participants of photovoice projects are considered ‘co-researchers’ or ‘peer-researchers’ (Roche et al., 2010, as cited in Houle et al., 2018) as they actively shape research goals and questions, data collection and analysis, and share their insights with relevant audiences (e.g., policy-makers). Other key roles in a photovoice project are the researcher who, as a ‘facilitator’, provides expertise on research practices (specifically photovoice methodology) and ensures that ethical standards are protected (e.g., data protection), as well as the audience which ideally includes relevant decision-makers who have the capacity to promote social change (Palibroda et al., 2009). Photovoice, like other participatory research methods, pursues power-sharing and equality between the different parties involved in the research process.

Photovoice methodology is often employed with the objective of improving people’s lives and has thus found particular use in research that addresses social issues such as poverty (e.g., Palibroda et al., 2009), violence (e.g., Chonody et al., 2013), drug misuse (e.g., D’Angelo & Her, 2019), gender and sexual identity-based discrimination (e.g., Capous-Desyllas & Akkouris, 2022; Cosgrove et al., 2021) and racism (e.g., Kessi & Cornell, 2015). Photographs — in combination with story-telling — are considered a particularly powerful tool to capture nuances in complex social contexts and to draw attention to social justice issues (Jarldorn, 2019; Wang & Burris, 1997). Since they provide insight into private and sensitive realities, it is particularly important to adhere to the ethical CBPAR-standards which include informed consent, confidentiality, safety, and protection of intellectual property (Kia-Keating et al., 2017).

Community-based participatory action research presents all participants with special challenges that should be recognized and addressed with foresight (Israel et al., 2012; Minkler & Wallerstein, 2003). For instance, CBPAR is a time-consuming and resource-demanding approach that requires long-term commitment by both community-members/Co-researchers and organizers/facilitators. A review of 21 photovoice projects noted that photovoice projects, on average, last between 21.3 (SD = 14.7) and 29.8 weeks (SD = 26.1) (Hergenrather et al., 2009). Scholars and practitioners further need the financial means and institutional support to conduct a photovoice project, be prepared to work with rather complex data and be committed to social change.

4 How can photovoice support diversity in social work?

In the following, we discuss three possible areas of application:

1. Understanding, empowering, and supporting clients through a lifeworld orientation

2. Enhancing social workers’ self-reflection on their own identity, role, and mission

3. Strengthening client-provider relationships

4.1 Photovoice as a tool to understand, empower, and support clients through a lifeworld orientation

Hans Thiersch’s (1978, 2020) lifeworld-oriented social work focuses on a comprehensive understanding and engagement with the daily realities and experiences of individuals and communities. It underscores the importance of respecting and valuing clients’ lived experiences, social contexts, and personal stories, with the aim of offering support that is not only responsive but empowering. This approach addresses the complexities of human lives by considering the socio-cultural, economic, and environmental factors that shape individuals’ lifeworlds, incorporating diverse dimensions of diversity. It advocates for customized interventions to meet unique needs and circumstances, with the objective of promoting autonomy, participation, and well-being by diminishing barriers and augmenting opportunities for positive transformation within individuals’ lifeworlds.

Photovoice emerges as a promising tool within the lifeworld-oriented approach, offering a platform for individuals, especially from underrepresented communities, to share their narratives and draw attention to the day-to-day challenges of their communities. For instance, Mitchell (2018) utilized photovoice to explore the effects of water insecurity on an indigenous community, while others have focused on immigrants and refugees (Brotman et al., 2020; Ferrer et al., 2022; Frisch et al., forthcoming; Lienen & LeRoux-Rutledge, 2022), individuals experiencing poverty or homelessness (e.g., Wang et al., 2000), those with disabilities (Dassah et al., 2017), and the transgender and LGBTQ+ communities (Pinheiro et al., 2024). Embracing feminist theory’s valuation of lived experiences as critical knowledge, photovoice posits individuals as experts of their own lives, offering perspectives that may be overlooked by external researchers and policymakers (Wang & Burris, 1997).

Photovoice is exceptionally adept at capturing the complex lived experiences from an intersectional lens, allowing participants to visually and narratively express how ethnicity, age, class, gender, and other diversity dimensions intersect to shape their experiences of inequality. The Prairie Women’s Health Centre of Excellence (PWHCE; Palibroda et al., 2019) has undertaken photovoice projects that delve into such intersectional experiences. While all projects focused on women’s health in Canada, Palibroda and colleagues (2019) placed attention to different areas such as poverty, “Aboriginal women’s health”, and “rural, remote and northern women’s health” (p. 2) to gain a more holistic understanding of the factors that influence women’s wellbeing. PWHCE considered health and well-being important prerequisites of social participation and photovoice a “fitting approach to revealing the depth and complexities of these issues” (Palibroda et al., 2019, p. 19). Other past photovoice projects also placed an explicit focus on intersectionality to better understand how factors like ageism, classism, and race shape the experience of disadvantaged groups (e.g., Brotman et al., 2020; Ferrer et al., 2022). Photographs can capture these complex experiences that remain to some extent unique to the photographer whilst some aspects may be shared with other members of the community, creating a sense of social cohesion.

Photovoice also endeavors to empower people and underprivileged communities to influence their life conditions and improve their well-being (Wang, 1999; Withofszky et al., 2020). Next to gathering a critical understanding of the challenges and concerns of a community, the goal is also to document its strengths and resources. Guided by this objective, Houle and colleagues (2018) employed photovoice in a public housing context in Canada. While previous research had mostly focused on challenges and problems that public housing tenants face, the ‘peer-researchers’ in this study also identified several facets that promoted their well-being, such as mutual support, access to nature, participation, and growth opportunities. They reported their work back to their community and community decision-makers through an exhibition of the photos and narratives. Feedback at the end of the project suggested that peer-researchers experienced ‘empowerment-related benefits’ at different levels through their participation in the photovoice project, such as a sense of recognition or a motivation to translate the results of the project into action. Other research that has qualitatively examined the empowerment potential of photovoice suggests that empowerment is achieved via a gain in knowledge, skills, and critical thinking/awareness (Budig et al., 2018; Malka et al., 2024; Teti et al., 2013), through the experience of recognition and feeling heard/having a voice (Budig et al., 2018; Koren & Mottola, 2022; Teti et al., 2013), by taking control and identifying room for action (Teti et al., 2013), or via access to new resources and social capital (Budig et al., 2018). However, to date, there has been a lack of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that confirm such narrative accounts of empowerment quantitatively (see also Liebenberg, 2018). Wang and Burris (1994) considered empowerment as “access to knowledge, access to decisions, access to networks, and access to resources” (p. 180, as cited in Liebenberg, 2018, p. 6), elements that must be considered from the outset when implementing photovoice methodology.

By allowing individuals to showcase social injustices through their lenses, photovoice catalyzes community and policy transformations. Such empowerment and visibility underscore the alignment of photovoice with the fundamental tenets of Thiersch’s lifeworld-oriented social work approach. It champions a holistic engagement with individuals’ and communities’ daily realities and experiences, reinforcing photovoice’s critical role in comprehensive understanding, empowering, and supporting social work clients. Through its unique ability to bridge the gap between personal narratives and systemic change, photovoice has the potential to enhance the efficacy of social work practice by fostering empathy, awareness, and action.

4.2 Photovoice as a tool for enhancing social workers’ self-reflection on their own identity, role, and mission

We advocate for broadening the scope of photovoice’s application to include fostering and deepening social workers’ self-reflection. Utilizing photovoice invites social workers to deeply introspect about their self-perception, their congruence with their organization’s values, and to conduct a thorough analysis of their professional practices. Importantly, it provides a critical platform for reevaluating their perceptions and understandings of the clients they support. This immersion in photovoice enables social workers to confront and critically reassess their preconceptions and biases, steering them towards practices that are more empathetic, culturally aware, and effective. This innovative adaptation of photovoice not only expands its utility but also establishes it as an indispensable tool for both personal and professional development in social work.

Furthermore, photovoice has demonstrated significant pedagogical value. Peabody (2013) leveraged the photovoice methodology to immerse students in social justice issues within a 10-week elective course focused on social work and public health. Students were encouraged to identify and discuss public health concerns impacting their communities, reflect on personal experiences of injustice, and delve into the theoretical frameworks underpinning photovoice. Participating in a photovoice project challenged students to critically assess the societal structures perpetuating inequalities and devise advocacy strategies utilizing their photographs to catalyze social change. Similarly, Bouchiș and colleagues (2021) employed photovoice methodology to foster a deeper understanding of diversity amongst Education Sciences students at the University of Oradea, Romania. Reflecting on the strengths and weaknesses of the education system through photovoice enabled these students to identify several ways in which the education system could be more inclusive to people with special education needs. The utility of photovoice as an educational tool extends to teaching research skills and fostering a critical appreciation of social work principles (Monteblanco & Moya, 2021), as well as enhancing self-awareness among social work students (Bromfield & Capous-Desyllas, 2017). In other academic fields, photovoice has been shown to enrich learning outcomes in culturally diverse settings by promoting increased engagement and participation. Specifically, it has enabled students to reflect on their multifaceted identities and deepen their comprehension of diversity (Chio & Fandt, 2007), demonstrating its versatile applicability and impact across various educational contexts.

Social workers are essential parts of the communities and organizations they serve, and their sense of belonging within these groups significantly impacts their well-being and work effectiveness. To delve into this, we initiated a photovoice project with social work students (N = 8) to examine their sense of belonging, aiming to foster a more inclusive atmosphere in the academic setting (Frisch & Mazziotta, in prep.). Belonging is understood as the “subjective feeling of being an integral part of one’s surrounding systems, such as family, friends, school, workplace, communities, cultural groups, and physical spaces” (Allen et al., 2021, p. 88). This encompasses feelings of emotional closeness, recognition and respect from one’s community, and the acknowledgment that one’s existence and contributions are valued, all of which are crucial for personal well-being and professional success (Cohen, 2022).

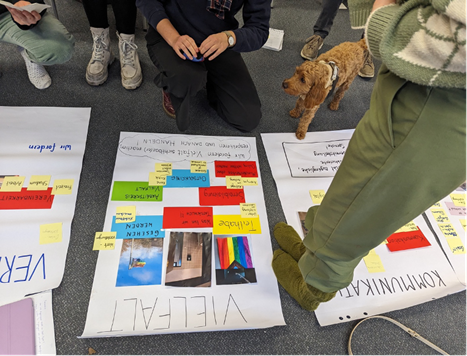

Figure 2 illustrates how students analyze their photographs, tell their narratives, and identify their needs. Our research identified several crucial factors that profoundly influence students’ sense of belonging: personal recognition – where students are seen as whole individuals with life responsibilities beyond their academic roles, such as balancing family obligations and employment; inclusive interactions – marked by equitable dialogue, a focus on leveraging resources, and the opportunity for constructive criticism; design of the physical spaces – considerations for varying mobility needs and spaces designated for relaxation and rejuvenation as well as visible symbols of diversity – the progress pride flag displayed in front of the building and the provision of all-gender restrooms, underscore the commitment to inclusivity. Through engaging with photovoice, students embarked on a journey of profound reflection concerning their varied social identities, the dynamics within their communities, and how these elements shape their future roles as social workers.

Figure 2: Participatory analysis in a photovoice project

Note. The results of the participatory analysis were used to derive requirements that are currently being evaluated in an exhibition within the student population. These results will then be discussed with decision-makers in order to increase the inclusivity of the department.

Additionally, a survey conducted alongside the photovoice project offered further insights into students’ senses of belonging and their specific needs. The results were shared at national educational conferences and with the leadership of the social work department, prompting meaningful discussions and leading to concrete actions. Motivated by the project’s outcomes, students championed changes to create a more welcoming learning environment, such as setting up a quiet space for relaxation and launching an online platform to assist incoming students. This application of photovoice not only illuminates the complex factors influencing social work students’ senses of belonging but also demonstrates the method’s potential as a valuable tool for social workers. It helps them explore their professional identities and understand the communities they are part of, ultimately enhancing their effectiveness and engagement in their work.

Another useful application of photovoice to improve social workers’ self-reflections may be to promote critical consciousness of their professional role in order to maintain their long-term well-being. Interestingly, photovoice studies have recently been applied with the aim of exploring burnout and self-care in the context of social work (Macy et al., 2024; Rahman et al., 2020). In one study, for example, sources of burnout and self-care techniques were explored at an individual, social, and organizational level (Rahman et al., 2020). On an individual level, self-care techniques included recognizing the need to maintain boundaries, perseverance, spiritual and religious beliefs, creativity, leisure activities, eating, and enjoying nature. On a social level, social support was most important. From the results, the researchers derived an action plan to improve work-life balance and called for, among other things, gym membership, offering in-house exercise and yoga classes, and providing recommendations to minimize role ambiguity and role conflict, for example, clear job descriptions, flexible work schedule programs, creating a general climate of emotional support through staff appreciation events, and offering open forums to employees, such as photovoice (Rahman et al., 2020). Organizations can benefit from photovoice by providing social workers with a cost-effective and safe space to reflect on their experiences. Photovoice can promote self-care and alleviate burnout by encouraging the development of new skills, such as identifying social problems, analyzing the problem in a group setting, and recommending changes through advocacy (Rahman et al., 2020). Promoting professional roles and minimizing role ambiguity can also strengthen the client-provider relationship by supporting clients with a clear and confident attitude.

4.3 Photovoice as a tool for strengthening the client-provider relationship

Leveraging insights from Hudson and Mehrotra's (2021) exploration of intersectional social work practices, we propose various approaches through which the photovoice methodology can fortify the client-provider relationship. From an intersectional standpoint, it is vital to recognize how cultural influences, social status, and power dynamics impact the client-provider relationship.

Reflexivity in photovoice compels social work practitioners to introspectively examine their positionality within the context of service provision (e.g., Malka, 2022). Positionality encompasses the practitioner’s theoretical perspectives, personal lived experiences, identity, and background, all of which shape interactions with clients. Practitioners may align with clients through shared characteristics such as race or gender, positioning themselves as insiders, or they may adopt an outsider stance by not sharing the same community ties (Gai, 2012, as cited in Hayfield & Huxley, 2015). An intersectional approach acknowledges that practitioners invariably maintain an outsider perspective to some degree, given the improbability of their positions being entirely congruent with those of the clients (see Versey, 2024). Reflexivity is heralded for enhancing quality (Sandelowski & Barroso, 2002), fostering a more transparent and critical examination of knowledge production and interpretation. In community-centered initiatives like photovoice, reflexivity assumes critical importance as the practitioner’s role diverges from that in conventional research methodologies (Houle et al., 2018). There is a noted concern that the proliferating use of photovoice has not been matched with adequate training in reflexivity (Liebenberg, 2018; Versey, 2024).

Crucial to this reflexivity is an active (and recurrent) reflection on the social worker’s own position relative to their clients, recognizing both similarities and differences. Such awareness is essential to circumvent the processes of othering and to avoid making unfounded assumptions about shared experiences which might lead to misunderstandings of the clients’ experiences due to perceived similarities. Research from the medical field suggests that photovoice can assist in this reflexivity process. Loignon and colleagues (2014) reviewed how medical residents benefitted from the photovoice methodology to reflect on their prejudices towards socioeconomically disadvantaged patients. With the support of their supervisors, they identified how their prejudice posed barriers to effective care which directly informed their subsequent professional behavior.

Understanding one’s positionality not only helps in acknowledging the unique experiences of each client but also in navigating the complex dynamics of similarity and difference, thereby fostering a more genuine and empathetic client-provider relationship. A study with 38 counseling students in the US empirically explored the potential of photographs and critical reflection in fostering empathy (Lenz & Sangganjanavanich, 2013). While a control group attended a traditional lecture on empathic communication, a treatment group participated in a “photovoice guided participatory visual analysis activity” (p. 45). In this activity, students were tasked with selecting two pre-taken photographs from a collection that reflected a social group, their culture, or lifestyle. Counselors-in-training then reflected on why they would prefer to engage with some groups over others, how they anticipated the counseling session might unfold, and discussed clients’ potential fears and hopes with the class. Before and after the intervention, students filled in a questionnaire and were asked to provide empathic responses to four vignettes that described different challenging scenarios in counseling settings. The pretest showed no significant differences in empathic responses; however, in the posttest, students who participated in the adapted photovoice task differed significantly and positively from the control group in their demonstration of empathic skills.

Photovoice methodology provides social workers with profound insights into clients’ perspectives, priorities, and challenges, paving the way for more empathetic and effective interventions rooted in a genuine comprehension of clients’ lifeworlds. By capturing their lived experiences through photographs and narratives, clients can discuss their needs more openly and engage in an authentic conversation with providers. Spotlighting both unique and shared community experiences can then help tailor interventions more effectively.

Photovoice serves as a potent advocacy tool. The concept of advocacy is intrinsically tied to the triple mandate of social work, emphasizing the proactive role that social workers must assume in addressing inequalities, discrimination, and social injustices. Social workers empower clients and communities by enabling access to, and control over, pertinent resources (see empowerment definition by Cornell University Empowerment Group, 1989, as cited in Wiley & Rappaport, 2000). Beyond financial means, service providers can enhance a community’s social capital and disseminate knowledge relevant to navigating institutional structures and advancing community interests. For example, in a photovoice project on disability rights concerns (Ollerton & Horsfall, 2013), the research team, under “the explicit direction of the co-researchers” (p. 626), disseminated disabled individuals’ concerns and photos to transportation authorities, informed various review boards and awareness programs. While the authors do not report on direct outcomes, they note that they received responses to their letters by the authorities. In a different photovoice project, public housing tenants transformed their photovoice results into concrete action by addressing waste management issues with the director of maintenance, managing the use of public laundry machines, and by gaining help from the city council in regulating the traffic in front of their homes (Houle et al., 2018). Through the visual documentation of social issues, photovoice contributes significantly to community and policy outreach. Photographs can be considered a particularly effective medium, as they concretize and persuade (Menegatti & Rubini, 2013), while also transmitting emotional intensity (Van Boven et al., 2010). A central objective of the photovoice methodology is to communicate insights to decision-makers to foster social change (Ferrer et al., 2022), although this objective is not always fully realized (Sanon et al., 2014).

Photovoice methodology could also be tailored to confront the challenges that both clients and practitioners face in realizing diversity objectives within their professional relationships. Photovoice provides a promising platform for clients to express their views on the essence of a diversity-sensitive relationship. The methodology facilitates the identification of overlooked areas and challenges, stemming from misunderstandings or an insufficient application of an intersectional lens in their engagement with social work professionals. Such transparent expression can shed light on the intricate details of client experiences, thereby enriching our understanding of the complexities related to identity and diversity within the social work domain.

Moreover, photovoice enables a critical examination of the power disparities that are intrinsic to the provider-client dynamic. Through the articulation of these power relations via visual and narrative means, it becomes possible for both clients and practitioners to recognize and address the effects of such imbalances on their interactions and, by extension, the efficacy of social work interventions. Acknowledging these power differentials is crucial for fostering a partnership that is both equitable and respectful.

Furthermore, the envisioning of a diversity-sensitive relationship through photovoice is inherently a collaborative and imaginative process. Clients and providers collaboratively generate visual narratives that represent their ideal of a respectful, understanding, and inclusive partnership. This collaborative creation not only establishes a benchmark for the aspirations of both parties but also serves as a continual reminder of the ongoing effort required to sustain such relationships amidst the changing landscapes of social identities and societal standards. This co-constructive approach holds the potential to broaden traditional social work dynamics, rendering the profession more attuned to the diverse realities faced by all stakeholders.

5 Critical reflection: Limitations, possible non-intended effects, and potential challenges of the implementation of photovoice in diverse societies

Several complexities and limitations warrant attention when considering how photovoice can serve a diversity-oriented social work.

The first challenge pertains to the frequently noted insufficient execution of photovoice methodology. Previous reviews have, for example, criticized that photovoice projects often do not fully adhere to participatory principles (e.g., Coemans et al., 2019; Hergenrather et al., 2009; Seitz & Orsini, 2022). Participatory action research stipulates the active involvement of community members in all steps of the research process, including deciding on the research focus and the procedure (Liebenberg, 2018). Yet, community concerns and priorities are often pre-determined by the facilitator of the project (Hergenrather et al., 2009), which violates the principle of power-sharing (Sitter, 2017). Linked to this critique, scholarly reviews have observed that the theoretical foundations of photovoice—specifically feminist theory, critical consciousness, and documentary photography—are occasionally overlooked in practical implementation. In a systematic review of 19 photovoice projects that focused on the empowerment of women, Coemans and colleagues (2019) found that few studies actually employed feminist theory. Only five reported that social change was achieved. Furthermore, few studies seem to systematically evaluate the effects and impacts of their photovoice project. This may stem from a temporal lag between the dissemination of outcomes (via exhibitions or scientific publications) and the tangible shifts in social or policy domains (Seitz & Orsini, 2022). It, however, limits, our understanding of photovoice’s potential in empowering marginalized communities. What these points demonstrate is that photovoice transcends mere data collection through photographs and narratives; it is a theory-informed methodology that demands careful deliberation to achieve its full effectiveness.

Given the focus of the current article on diversity, it is critical to acknowledge that photovoice, much like other research methodologies, does not achieve complete inclusivity. Photovoice is a flexible method to the extent that it does not require community members to be literate (Hergenrather et al., 2009) but it is still not equally accessible to all population groups. Beyond people with impaired vision, the method can pose challenges to people living with certain physical disabilities or restrictions (e.g., the elderly) who may not be able to enter all spaces that they would like to photograph (Dassah et al., 2017; Lal et al., 2012; Mysyuk & Huisman, 2020 as cited in Seitz & Orsini, 2022). Other groups may not have the means to travel to the meeting points where group discussions are held (e.g., homeless people) or be hesitant to discuss and document their experiences due to vulnerability (e.g., migrants without legal protection), although organizers can enhance inclusivity by providing compensation and/or data protection. Finally, Lal and colleagues (2012, as cited in Seitz & Orsini, 2022) have noted that it is challenging to conduct critical discussions with children, suggesting that the method is more suitable for working with adults.

Furthermore, there may be potential negative, unintended outcomes of a photovoice project. For instance, if people reflect on challenges and structural barriers but are not aware of the protracted nature of social change, the process may be experienced as dis-empowering rather than empowering by community members (Coemans et al., 2019). Similarly, the political process of social change could be perceived as threatening (Israel et al., 2012; Minkler et al., 2003). On the other hand, social problems could become solidified rather than changed if, for example, there is no viable opportunity for community action or change (e.g. Greene et al., 2018; Hannes & Parylo, 2014; Wang & Burris, 1997; Wang & Redwood-Jones, 2001).

An important question within diversity-oriented social work is how diversity attributions may reinforce social categories and further discriminate people. Within social work, needs are, to some extent, assessed and resources allocated according to people’s social categories. Power dynamics play a central role here and it is relevant to ask: who determines diversity categories and identities? Are these attributions externally imposed (and interpreted), or are they self-attributed? One can consider the essentialization of people through group attribution as problematic, not least because these are often tainted with negative stereotypes (Leiprecht, 2008). At the same time, it may even be necessary for people to ascribe themselves to these categories to qualify for institutional support (Castro Varela & Wrampelmeyer, 2021). Following a still dominant understanding of diversity, many services, however, consider different dimensions of diversity separately or summative and rarely from an intersectional perspective (Castro Varela & Wrampelmeyer, 2021). Within intersectional approaches, some also see danger in a reduced use of the perspective in social or educational work when intersectionality is used to capture clients with as much detail as possible by considering a variety of differences, but also to define them and potentially better manage and control them (Riegel, 2010, as cited in Rein and Riegel, 2016, p. 76). Further, while the Federation of Social Workers champions ideals of social change, “development, social cohesion, and the empowerment and liberation of people” (Global Definition of Social Work, n.d., para. 4), it is important to acknowledge the enduring power asymmetry between social workers and their clients, as the allocation of resources remains in the jurisdiction of the former. That is, by integrating photovoice and an intersectional lens, service providers can gain deeper insight into their clients’ lived experiences and involve them in the solution process, but the ultimate decision-making authority still resides with the providers themselves and their employers.

Social workers may be concerned that their already limited resources will not allow for a complex and time-consuming photovoice engagement. A shortage of skilled labor and high administrative burdens are already making their work more difficult. Exploring collaborative partnerships with universities may present a viable avenue here for integrating theoretical knowledge with practical application, thereby supporting social workers in effectively fulfilling their third mandate of promoting social justice.

Finally, we discussed how clients of social work can experience empowerment through the use of photovoice. The method helps identify a community’s challenges and strengths that may then be built upon to advocate for social change. Empowerment, however, is no uncontroversial concept within the social sciences (Weidenstedt, 2016); scholars have questioned the longevity of empowerment and to what extent people actually gain better access to relevant resources. Houle and colleagues (2018) further caution that the responsibility for community well-being cannot lie exclusively with its members; achieving structural change requires first and foremost political support and will.

6 Conducting a photovoice project to foster diversity in social work - Practical considerations

With the preceding section, we do not intend to discourage practitioners from employing photovoice methodology in their work. We believe, to the contrary, that a rigorous application of photovoice methodology has the potential to foster a more nuanced and diversity-sensitive relationship between social work providers and their clients. In this final segment of our article, we therefore summarize some practical recommendations and critical reflections shared by scholars within the community. For more comprehensive and detailed practical guidelines, readers are encouraged to explore the works of Jarldorn (2019), Palibroda and colleagues (2009), or Wang and Burris (1997), to name just a few.

Building on insights from a systematic review of 19 photovoice projects, Coemans and colleagues (2019) offer practical considerations to scholars and practitioners who seek to apply photovoice in their work, particularly within a feminist framework. Their recommendations underscore the need for methodological and theoretical expertise, emphasizing the value of a team with a diverse set of skills such as facilitating empowerment processes and bringing together diverse stakeholders. Social workers, with their nuanced understanding of community dynamics, are discussed as particularly well-positioned to support in this process (p. 59). The authors also encourage photovoice practitioners to transparently articulate their intentions when invoking the concept of “giving voice”, as many photovoice projects still seem to focus more strongly on scientific insight than empowerment. Similarly, they stress that photovoice practitioners must immerse themselves in the theoretical foundations of photovoice, including feminist theory and critical consciousness. Within this context, an evaluation of whether empowerment was actually achieved would further strengthen the work. An additional quality criterion could be to have co-researchers determine empowerment outcomes (Rappaport, 1987, as cited in Coemans et al., 2019). To navigate this terrain effectively, photovoice practitioners must engage in critical self-reflection regarding their own positionality (e.g., through a positionality statement; see also Sitter, 2017) and their own position of power. Hergenrather and colleagues (2009) add that the role of the project organizer should be clearly communicated as “process-facilitating” to foster commitment by both parties and amplify the valuable expertise contributed by community members. Coemans and colleagues (2019) further propose placing photos at the center of project reports, as they constitute the essence of the method, yet they are often relegated to a supporting role in favor of qualitative insights. Finally, the authors caution against overlooking negative outcomes that may arise from photovoice projects. This aligns with the broader call for thorough evaluations - specifically concerning empowerment outcomes - within photovoice projects. We would add to this list that social workers incorporating photovoice into their practice should be mindful about the intersectional identities and forms of oppression that shape their clients’ experiences. This involves providers being considerate about who determines which diversity dimensions are focused on and who ascribes these. It further means creating space for shared experiences arising from intersecting identities, as well as acknowledging each individual’s unique lifeworld.

Finally, depending on whether the focus is more strongly placed on social work practice or on gaining (academic) knowledge, the implementation of the method can vary greatly. It is therefore important to engage in a realistic discussion about practicalities like access to populations or resources before starting photovoice projects (see Jarldorn, 2019, chapter 3, for guidance).

7 Conclusion

The present article explored how the photovoice method can benefit diversity in the social work field. Along three areas of application, we reviewed how photovoice can 1) support the understanding and empowerment of clients through a lifeworld orientation, 2) enhance social workers’ self-reflection on their own identity, role, and mission, and 3) strengthen the client-provider relationships. We hope readers leave this article inspired and empowered to incorporate photovoice in their professional practice.

References:

Allen, K. A., Kern, M. L., Rozek, C. S., McInereney, D., & Slavich, G. M. (2021). Belonging: A review of conceptual issues, an integrative framework, and directions for future research. Australian Journal of Psychology, 73(1), 87–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049530.2021.1883409

Aschenbrenner-Wellmann, B., & Geldner, L. (2021). Diversität in der Sozialen Arbeit: Theorien, Konzepte, Praxismodelle [Diversity in social work: theories, concepts, practice models]. W. Kohlhammer. https://doi.org/10.17433/978-3-17-033069-6

Baylor School of Social Work Team. (2022, March 6). Why an understanding of diversity is important to social work. Baylor University. https://gsswstories.baylor.edu/blog/why-an-understanding-of-diversity-is-important-to-social-work

Bernard, C. (2021). Intersectionality for social workers: A practical introduction to theory and practice. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429467288

Bouchiș, L. N., Popa, C. A., Petre, G.-E., Fitzgerald, S. L., & Vesa, A. (2021). Exploring diversity in special education: A participatory action research with photovoice. In O. Clipa (Ed.), Challenges in Education: Policies, Practice and Research (pp. 7 - 32). Peter Lang.

Bromfield, N. F., & Capous-Desyllas, M. (2017). Photovoice as a pedagogical tool: Exploring Personal and professional values with female Muslim social work students in an intercultural classroom setting. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 37(5), 493–512. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841233.2017.1380744

Brotman, S., Ferrer, I., & Koehn, S. (2020). Situating the life story narratives of aging immigrants within a structural context: the intersectional life course perspective as research praxis. Qualitative Research, 20(4), 465–484. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794119880746

Budig, K., Diez, J., Conde, P., Sastre, M., Hernán, & Franco, M. (2018). Photovoice and empowerment: evaluating the transformative potential of a participatory action research project. BMC Public Health, 18, 431. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5335-7

Burkard, A. W., Edwards, L. M., & Adams, H. A. (2015). Racial color blindness in counseling, therapy, and supervision. In H. A. Neville, M. E. Gallardo, & D. W. Sue (Eds.), The myth of racial color blindness: Manifestations, dynamics, and impact (pp. 295-311). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/14754-018

Capous-Desyllas, M., & Akkouris, M. (2022). We're here, we're queer, we're framed: Navigating ethical tensions in a photovoice project with LGBTQ+ refugees and asylum seekers living in Athens, Greece. Global public health, 17(10), 2590–2603. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2021.1989475

Castro Varela, M. d. M., & Wrampelmeyer, S. (2021). Diversity. In R.-C. Amthor, B. Goldberg, P. Hansbauer, B. Landes, & T. Wintergerst (Eds.), Kreft/Mielenz Wörterbuch Soziale Arbeit. Aufgaben, Praxisfeld, Begriffe und Methoden der Sozialarbeit und Sozialpädagogik (pp. 201- 205). Julius Beltz GmbH & Co. KG.

Chio, V. C. M., & Fandt, P. M. (2007). Photovoice in the diversity classroom: Engagement, voice, and the “eye/I” of the camera. Journal of Management Education, 31(4), 484–504. https://doi.org/10.1177/1052562906288124

Chonody, J., Ferman, B., Amitrani-Welsh, J., & Martin, T. (2013). Violence through the eyes of youth: A photovoice exploration. Journal of Community Psychology, 41(1), 84-101. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.21515

Coemans, S., Raymakers, A. L., Vandenabeele, J., & Hannes, K. (2019). Evaluating the extent to which social researchers apply feminist and empowerment frameworks in photovoice studies with female participants: A literature review. Qualitative Social Work, 18(1), 37-59. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325017699263

Cohen, G. L. (2022). Belonging: The science of creating connection and bridging divides. Norton & Company.

Combahee River Collective (1977). The Combahee River Collective Statement. https://americanstudies.yale.edu/sites/default/files/files/Keyword%20Coalition_Readings.pdf

Cosgrove, D., Bozlak, C., & Reid, P. (2021). Service barriers for gender nonbinary young adults: Using photovoice to understand support and stigma. Affilia: Journal of Women & Social Work, 36(2), 220–239. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886109920944535

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol1989/iss1/8

D’Angelo, K. A., & Her, W. (2019). 'The drug issue really isn’t the main problem'—A photovoice study on community perceptions of place, health, and substance abuse. Health & Place, 57, 257–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2019.05.001

Dassah, E., Aldersey, H. M., & Norman, K. E. (2017). Photovoice and persons with physical disabilities: A scoping review of the literature. Qualitative Health Research, 27(9), 1412-1422. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732316687731

DiTomaso, N. (2021). Why difference makes a difference: Diversity, inequality, and institutionalization. Journal of Management Studies, 58(8), 2024–2051. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12690

DiTomaso, N., Post, C., & Parks-Yancy, R. (2007). Workforce diversity and inequality: Power, status, and numbers. Annual Review of Sociology, 33, 473501. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.33.040406.131805

Ferrer, I., Brotman, S., & Koehn, S. (2022). Unravelling the interconnections of immigration, precarious labour and racism across the life course. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 65(8), 797–821. https://doi.org/10.1080/01634372.2022.2037805

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Seabury.

Freire, P. (1973). Education for critical consciousness. Continuum.

Greene, S., Burke, K. J., & McKenna, M. K. (2018). A review of research connecting digital storytelling, photovoice, and civic engagement. Review of Educational Research, 88(6), 844-878. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654318794134

Grunwald, K., & Thiersch, H. (2009). The concept of the ‘lifeworld orientation’ for social work and social care. Journal of Social Work Practice, 23(2), 131-146, https://doi.org/10.1080/02650530902923643

Hannes, K., & Parylo, O. (2014). Let’s play it safe: Ethical considerations from participants in a photovoice research project. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 13(1), 255-274. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940691401300112

Hayfield, N., & Huxley, C. (2015). Insider and outsider perspectives: Reflections on researcher identities in research with lesbian and bisexual women. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 12(2), 91-106. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2014.918224

Hergenrather, K. C., Rhodes, S. D., Cowan, C. A., Bardhoshi, G., & Pula, S. (2009). Photovoice as community-based participatory research: A qualitative review. American Journal of Health Behavior, 33(6), 686–698. https://doi.org/10.5993/ajhb.33.6.6

Houle, J., Coulombe, S., Radziszewski, S., Boileau, G., Morin, P., Leloup, X., Bohémier, H., & Robert, S. (2018). Public housing tenants’ perspective on residential environment and positive well-being: An empowerment-based Photovoice study and its implications for social work. Journal of Social Work, 18(6), 703–731. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468017316679906

Hudson, K. D., & Mehrotra, G. R. (2021). Intersectional social work practice: A critical interpretive synthesis of peer-reviewed recommendations. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 102, 140–153. https://doi.org/10.1177/1044389420964150

International Federation of Social Workers. (n.d.). Global Definition of Social Work. https://www.ifsw.org/what-is-social-work/global-definition-of-social-work/

Israel, B. A., Eng, E., Schulz, A. J., & Parker, E. A. (2012). Methods for community-based participatory research for health (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Jarldorn, M. (2019). Photovoice handbook for social workers: Method, practicalities and possibilities for social change. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-94511-8

Kessi, S., & Cornell, J. (2015). Coming to UCT: Black students, transformation and discourses of race. Journal of Student Affairs in Africa, 3, 1-16. https://doi.org/10.14426/JSAA.V3I2.132

Kia-Keating, M., Santacrose, D., & Liu, S. (2017). Photography and social media use in community-based participatory research with youth: Ethical considerations. American Journal of Community Psychology, 60, 375-384. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12189

Koren, A., & Mottola, E. (2022). Marginalized youth participation in a civic engagement and leadership program: Photovoice and focus group empowerment activity. Journal of Community Psychology, 51, 1756-1769. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22959

Lal, S., Jarus, T., & Suto, M. J. (2012). A Scoping Review of the Photovoice Method: Implications for Occupational Therapy Research. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 79(3), 181-190. https://doi.org/10.2182/cjot.2012.79.3.8.

Leiprecht, R. (2008). Diversity Education und Interkulturalität in der Sozialen Arbeit [Diversity education and interculturality in social work]. Sozial Extra, 32(11), 15–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12054-008-0102-0

Lenz, A. S., & Sangganjanavanich, V. F. (2013), Evidence for the utility of a photovoice task as an empathic skill acquisition strategy among counselors-in-training. The Journal of Humanistic Counseling, 52, 39-53. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1939.2013.00031.x

Liebenberg, L. (2018). Thinking critically about photovoice: Achieving empowerment and social change. International journal of qualitative methods, 17(1). https://doi.org/1609406918757631.

Lienen, C. S., & LeRoux-Rutledge, E. (2022). Refugee identity and integration in Germany during the European “Migration Crisis”: Why local community support matters, and why policy gets it wrong. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/15562948.2022.2098445

Loignon, C., Boudreault-Fournier, A., Truchon, K., Labrousse, Y., & Fortin, B. (2014). Medical residents reflect on their prejudices toward poverty: a photovoice training project. BMC Medical Education, 14(1), 1050. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-014-0274-1

Lott, B. (2010). Multiculturalism and diversity: A social psychological perspective. Wiley-Blackwell.

Macy, G., Harper, W., Murphy, A., Link, K., Griffiths, A., Win, S., & East, A. (2024). Using concepts of photovoice to engage in discussions related to burnout and wellbeing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(2), 192. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph21020192

Maguire, P. (1987). Doing Participatory Research: A Feminist Approach. Center for International Education.

Malka, M. (2022). Photo-voices from the classroom: photovoice as a creative learning methodology in social work education. Social Work Education, 41(1), 4-20. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2020.1789091

Malka, M., Edelstein, O. E., Huss, E., & Lavian, R. H. (2024). Boosting resilience: Photovoice as a tool for promoting well-being, social cohesion, and empowerment among the older adult during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 43(9), 1183-1193. DOI: 10.1177/07334648241234488

Mattsson, T. (2014). Intersectionality as a useful tool: Anti-oppressive social work and critical reflection. Affilia, 29(1), 8-17. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886109913510659

Menegatti, M., & Rubini, M. (2013). Convincing similar and dissimilar others: The power of language abstraction in political communication. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39(5), 596-607. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167213479404

Micsky, T., & John-Danzell, N. (2021). Practicing self-care: Integrating a photovoice self-care assignment into a social work course. Journal of Baccalaureate Social Work, 26(1), 55–67. https://doi.org/10.18084/1084-7219.26.1.55

Minkler, M., Blackwell, A. G., Thompson, M., & Tamir, H. (2003). Community-based participatory research: implications for public health funding. American Journal of Public Health, 93(8), 1210–1213. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.93.8.1210

Minkler, M., & Wallerstein, N. (2003). Introduction to community based participatory research. Community-based participatory research for health (pp. 3–26). Jossey-Bass/Wiley.

Mitchell, F. M. (2018). “Water is life”: Using photovoice to document American Indian perspectives on water and health. Social Work Research, 42(4), 277–289. https://doi.org/10.1093/swr/svy025

Molloy, J. K. (2007). Photovoice as a tool for social justice workers. Journal of Progressive Human Services, 18(2), 39–55. https://doi.org/10.1300/J059v18n02_04

Monteblanco, A. D., & Moya, E. M. (2021). Photovoice: Integrating course-based research in undergraduate and graduate social work education. British Journal of Social Work, 51(2), 712–732. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcaa154

Müller, D. & Polat, A. (2022) Intersektionale Perspektiven als Chance für die Soziale Arbeit in Forschung, Theorie und Praxis [Intersectional perspectives as an opportunity for social work research, theory, and practice]. In A. B. Mefebue, A. D. Bührmann, & S. Grenz (Eds.), Handbuch Intersektionalitätsforschung (pp. 381 – 395). Springer VS. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-26292-1

Ollerton, J. & Horsfall, D. (2013). Rights to research: utilising the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities as an inclusive participatory action research tool. Disability & Society, 28(5), 616-630. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2012.717881

Palibroda, B., Krieg, B., Murdock, L., & Havelock, J. (2009). A practical guide to Photovoice: Sharing pictures, telling stories and changing communities. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/A-PRACTICAL-GUIDE-TOPHOTOVOICE:-SHARING-PICTURES,-Palibroda-Krieg/e408d2b8fbf98f4aad7e8e706722dad1ff34014a#paperheader

Peabody, C. G. (2013). Using photovoice as a tool to engage social work students in social justice. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 33(3), 251-265. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841233.2013.795922

Perko, G., & Czollek, L. C. (2022). Lehrbuch Gender, Queer und Diversity (2nd ed.). Beltz Juventa.

Petschel, A. (2021, March 10). Datenreport 2021: Kinder mit Migrationshintergrund. Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung [Data Report 2021: Children with a migration background. German Federal Agency for Civic Education]. https://www.bpb.de/kurz-knapp/zahlen-und-fakten/datenreport-2021/bevoelkerung-und-demografie/329526/kinder-mit-migrationshintergrund/

Pinheiro, D., Araújo, L., & Sousa, L. (2024). The use of photovoice with the LGBTQIA+ community: A systematic review. Journal of LGBTQ Issues in Counseling, 18(1), 3-25. https://doi.org/10.1080/26924951.2023.2295811

Rahman, R., Ghesquiere, A., Spector, A. Y., Goldberg, R., & Gonzalez, O. M. (2020). Helping the helpers: A photovoice study examining burnout and self-care among HIV providers and managers. Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership & Governance, 44(3), 244–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/23303131.2020.1737293

Rein, A., & Riegel, C. (2016). Heterogenität, Diversität, Intersektionalität: Probleme der Vermittlung und Perspektiven der Kritik [Heterogeneity, diversity, intersectionality: problems of mediation and perspectives of critique]. In M. Zipperle, P. Bauer, B. Stauber, & R. Treptow (Eds.), Vermitteln: Eine Aufgabe von Theorie und Praxis Sozialer Arbeit (pp. 67-84). Springer VS. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-08560-5_6

Sandelowski, M., & Barroso, J. (2002). Finding the findings in qualitative studies. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 34(3), 213–219. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.2002.00213.x

Sanon, M.-A., Evans-Agnew, R. A., & Boutain, D. M. (2014). An exploration of social justice intent in photovoice research studies from 2008 to 2013. Nursing Inquiry, 21(3), 212-226. https://doi.org/10.1111/nin.12064

Seitz, C. M., & Orsini, M. M. (2022). Thirty years of implementing the photovoice method: Insights from a review of reviews. Health Promotion Practice, 23(2), 281-288. doi:10.1177/15248399211053878

Shaffer, R. (1983). Beyond the dispensary. African Medical and Research Foundation. https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/19852023923

Sitter, K. C. (2017). Taking a closer look at photovoice as a participatory action research method. Journal of Progressive Human Services, 28(1), 36–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/10428232.2017.1249243

Staub-Bernasconi, S. (2018). Soziale Arbeit als Handlungswissenschaft: Soziale Arbeit auf dem Weg zu kritischer Professionalität [Social work as a science of action: Social work on the way to critical professionalism] (2nd ed.). utb GmbH. https://doi.org/10.36198/9783838547930

Stryker, R. E. (1963). Documentary photography. In Encyclopedia of Photography. Greystone.

Tao, K. W., Owen, J., Pace, B. T., & Imel, Z. E. (2015). A meta-analysis of multicultural competencies and psychotherapy process and outcome. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 62(3), 337–350.

Teti, M., Pichon, L., Kabel, A., Farnan, R., & Binson, D. (2013). Taking pictures to take control: Photovoice as a tool to facilitate empowerment among poor and racial/ethnic minority women with HIV. The Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care: JANAC, 24(6), 539–553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jana.2013.05.001

Thiersch, H. (1978). Die hermeneutisch-pragmatische Tradition der Erziehungswissenschaft [The hermeneutic-pragmatic tradition of educational science]. In H. Thiersch, H. Ruprecht, & U. Herrmann (Eds.), Die Entwicklung der Erziehungswissenschaft (pp. S. 11–108). Juventa.

Thiersch, H. (2020). Lebensweltorientierte Soziale Arbeit – revisited [Lifeworld-oriented social work - revisited]. Beltz Juventa.

Van Boven, L., Kane, J., McGraw, A. P., & Dale, J. (2010). Feeling close: Emotional intensity reduces perceived psychological distance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(6), 872-885. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019262

Versey, H. S. (2024). Photovoice: A method to interrogate positionality and critical reflexivity. The Qualitative Report, 29(2), 594-605. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2024.5222

Wang, C. C. (1999). Photovoice: A participatory action research strategy applied to women's health. Journal of women's health, 8(2), 185-192. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.1999.8.185

Wang, C., & Burris, M. A. (1994). Empowerment through photo novella: Portraits of participation. Health Education Quarterly, 21(2), 171–186. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019819402100204

Wang, C., & Burris, M. A. (1997). Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health education & behavior, 24(3), 369-387. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019819702400309

Wang, C., Burris, M. A., & Xiang, Y. P. (1996). Chinese village women as visual anthropologists: A participatory approach to reaching policymakers. Social science & medicine, 42(10), 1391-1400. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(95)00287-1

Wang, C. C., Cash, J. L., & Powers, L. S. (2000). Who knows the streets as well as the homeless? Promoting personal and community action through photovoice. Health Promotion Practice, 1(1), 81-89. https://doi.org/10.1177/152483990000100113

Wang, C., & Redwood-Jones, Y. A. (2001). Photovoice ethics: Perspectives from Flint photovoice. Health Education & Behavior: The Official Publication of the Society for Public Health Education, 28(5), 560-572. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019810102800504

Weidenstedt, L. (2016). Empowerment gone bad: Communicative consequences of power transfers. Socius: Sociological research for a dynamic word, 2, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1177/2378023116672869

White-Davis, T., Stein, E., & Karasz, A. (2016). The elephant in the room: Dialogues about race within cross-cultural supervisory relationships. The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 51(4), 347–356. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091217416659271

Wihofszky, P., Hartung, S., Allweiss, T., Bradna, M., Brandes, S., Gebhardt, B., & Layh, S. (2020). Photovoice als partizipative Methode: Wirkungen auf individueller, gemeinschaftlicher und gesellschaftlicher Ebene [Photovoice as a participatory method: individual, community and social level effects]. In S. Hartung, P. Wihofszky, & M. T. Wright (Hrsg.). Partizipative Forschung. Ein Forschungsansatz für Gesundheit und seine Methoden (pp. 85-141). Springer VS. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-30361-7_4

Wiley, A., & Rappaport, J. (2000). Empowerment, wellness, and the politics of development. In D. Cicchetti, J. Rappaport, I. Sandler, & R. P. Weissberg (Eds.), The promotion of wellness in children and adolescents (pp. 59–99). Child Welfare League of America.

Williams, F. (1989). Social policy: A critical introduction. Polity Press.

Author´s Address:

Dr. Carmen S. Lienen

FernUniversität in Hagen

Community Psychology

Universitätsstr. 37, 58097 Hagen

carmen.lienen@fernuni-hagen.de

https://www.fernuni-hagen.de/community-psychology/team/carmen.lienen.shtml

Author´s Address:

M.Sc. Andrea Monica Frisch

FernUniversität in Hagen

Community Psychology

Universitätsstr. 37

58097 Hagen

andrea.frisch@studium.fernuni-hagen.de

Author´s Address:

Prof. Dr. Agostino Mazziotta

FH Münster, University of Applied Sciences

Fachbereich Sozialwesen

Hüfferstraße 27

48149 Münster

agostino.mazziotta@fh-muenster.de

Author´s Address:

Prof. Dr. Anette Rohmann

Chair of Community Psychology, FernUniversität in Hagen

Universitätsstr. 37

58097 Hagen

Anette.Rohmann@fernuni-hagen.de

https://www.fernuni-hagen.de/community-psychology/