The implementation of social policies in a pandemic context: an analysis of anger

Andrea Dettano, National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET)

Rebeca Cena, National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET)

Abstract: The pandemic context put into operation social policies that sought to accompany the difficulties in earning an income. Against this background, social policies acquired a visible centrality in state agendas, dedicated to dealing with the health emergency caused by COVID-19. In the Argentine case, a policy called Emergency Family Income (EFI) was implemented, consisting of a cash transfer intended to mitigate the loss of income generated by Social, Preventive, and Compulsory Isolation (SPCI). The EFI’s management, implementation, access, and collection method underwent a digitalisation process, enabling access through official and nonofficial channels. Among nonofficial channels there are Facebook Groups, where the beneficiaries of social policies exchange information, doubts, and advice. Its application and actual access encountered several obstacles and engendered different emotions. As part of a virtual ethnography in a Facebook group, this paper develops -from the social studies of emotions-, how anger unfolds in the collection of a social policy. The analysis of emotions in state interventions allows us to reformulate the study of the implementation processes. The main findings are 1) anger appears as a product of the mismatch between expectation and experience in the face of irregular operations in its implementation; 2) anger presents a binding and supportive character that is shared in the search for empathy and is reinforced by sharing it; 3) it is driven by the evaluations of deserving/not deserving subsidies 4) politicians and different leaders are regarded as legitimate recipients. The conclusions highlight the central place that anger holds in the implementation of social policies. Studying anger allows us to shed light on the obstacles and the practices involved in state interventions and thus improve the implementation processes of social policies based on the experiences of the recipient population. It also makes it possible to identify some guidelines for improving government interventions, such as help with digitalisation processes; provide clear and uniform information; comply with regular payments; assist recipients; and promote government transparency.

Keywords: Pandemic; Anger; Social Policies; Emotions; Social Networks.

1 Introduction: Social policies, pandemic, and emotional worlds

In the 21st century, social policies present some key features: a backbone character, massiveness, a banking and monetization implication, deployment in the digital/virtual world, an intergenerational presence in the recipient population, as well as their survival, as they overlap and sustain interventions over time.

As recent research reveals, emotions constitute a central aspect of studies on state interventions. They are present in the design of social policies and affect the implementation processes. This accounts for the fact that these interventions impact on material and symbolic aspects and affect bodies/emotions in all their complexity (MacAuslan & Riemenschneider 2011; Tonkens et al 2013; De Sena & Scribano 2020; Van de Velde, 2020; Dettano & Cena 2021; Cena & Dettano 2022; Betzelt & Bode 2022; Jupp 2022).

As Agnes Heller points out, “Throughout history, humans have been given various tasks. They must produce to fulfill the demands and potentials of their respective modes of production, contribute to the development of both themselves and the social framework into which they are born. Among these responsibilities, individuals must also address their own unique challenges. The nature of these tasks influences the emotions that arise, dictating their intensity, frequency, and potential dominance” (1980: 229). It is as from the organization of tasks that “sentimental worlds” are configured in societies, as the author will say (230). The various tasks configure different ways of life that are unequally valued in society. These sentimental worlds are modelled on the actions of the subjects and organised according to prescriptions and norms. It is the multiple determinants that the subjects “bear” such as age, gender, educational level, and income that influence and make up the emotional life (Schieman 2006). In this way, in contemporary social structures such as those of the 21st century, marked by the widespread adoption of information and communication technologies, the heterogeneity of the labour market, and extensive state interventions aimed at addressing poverty and unemployment, multiple stratifications and inequalities are part of the worlds of life. These societal structures facilitate different positions that organize complex, overlapping and changing emotional worlds.

Added to this set of features is the COVID-19 pandemic, which not only meant different forms of isolation depending on the country (Scott, Greer, Holly Jarman, Falkenbach, Massard, Minakshi & Elizabeth 2021; Nercesian, Cassaglia & Morales Castro, 2021; Martínez Franzoni & Sánchez Ancochea, 2022) but also a battery of state interventions aiming to compensate for the loss of income. In the Argentine case, the health emergency implications on households were profound, leading to job losses, decreased income, restricted consumption of certain food groups, as well as different forms of indebtedness.

In this paper, within the range of feelings that the pandemic context involved, we intend to explore anger as an emotion associated with the management, participation, and collection of a massive social policy created for this context: The Emergency Family Income (EFI). Anger is the product of social interaction (something we do or don't do in our relationship with other people) and emerges as a perception of a situation that is felt as unfair. It is a form of behaviour-oriented toward what we are angry with (Crossley 1995). It is not an “internal” or “individual” emotional state; it is “'publicly verifiable aspects of embodied conduct or behaviours'” (Crossley 1995: 143 cited in Holmes 2004: 123). In this way, social issues, social problems, and social policies show us a "kaleidoscope" to thematize an extended, reiterated, and reinforced emotion in the pandemic context: anger.

2 About anger

Emotions are an element that appears repeatedly in the experience through state interventions since they dialogue with the material conditions of existence. In the context of a pandemic, the flow of state interventions in operation are added to those directly involved in the care or (as various official documents mention) containment of the social problems. Within the different interventions deployed (such as the increase in budget items for soup kitchens, the utilities price cap and regulation of the maximum prices of essential services, the increase in the amount transferred to recipients of the Universal Child Allowance for Social Protection, among other measures), EFI was implemented through the National Social Security Administration. The EFI consisted of a monetary transfer of 10,000 pesos[1] aimed at informal workers, unemployed people, those registered as self-employed or autonomous workers from the lowest categories, recipients of some social programs, and other employment situations[2]. The EFI was profoundly impacted by digitalisation since its inception, registration, and monitoring. This had also affected they way people engaged with and accessed registration procedures as well as the massive organisation of the program in virtual environments such as Facebook groups. The EFI aimed to "compensate for the loss or decrease in income of people affected by the sanitary emergency declared by the coronavirus pandemic”. Although the SPCI lasted for ten months in Argentina, the program was not paid monthly but rather had three discontinuous editions that were announced as the lockdown period was extended. The 8.9 million people who received the benefits of the EFI represented 44 per cent of Argentina’s Economically Active Population (EAP) (ANSES 2020).

The implementation of the EFI was entirely online, reinforcing a trend that had already been observed in social policies (Criado 2022), which aroused different feelings. Its implementation together with the hundreds of thousands of enquiries and comments displayed on social media have made it possible to observe a network of feelings or sentimental worlds, as Agnes Heller ([1980] 2004) would say, that account for the practices carried out to make the payment of the benefit effective together with the difficulties that this task entails.

In the analysis of this massive social policy, we have identified different dimensions of uncertainty linked to the impossibility of establishing certainties about an fixed payment calendar, management and access modes and the continuity of the benefit. The constant doubts led potential recipients to resort to different social media platforms in search of information while going through all the available consultation channels. Uncertainty is generated and reinforced not only by the large number and overlapping doubts about how to access it but also when realizing that some aspects of the subsidy are arbitrary. There is no understanding of situations that are not related to the implementation rules of the policy: there are operations and cases (presented by the members of the Facebook Groups) that contradict the policy requirements. The answers to the queries they make in the group are rife with contradictions, which blur the reference framework that would serve to guide the practices (Dettano & Cena, 2021).

The characteristics of such context as sudden and novel as the pandemic, in addition to organising multiple uncertainties, have also given rise to various allusions to waiting. In the analysis of the waiting, it is observed that it unfolds in relation to different temporary segments. Acknowledging the wait when managing a social policy appears as an activity and disposition that the beneficiaries know and manage, revealing their past experience with state interventions: they “know” about waiting. The course of waiting -the present- is not merely a passive moment; rather, it is a time full of tasks such as negotiations and intra-group consultations to cope with the array of feelings that it elicits, from anger to fatigue. Likewise, the future appears full of uncertainties regarding the collection of the benefits as well as the possibility of establishing new benefits such as a Citizen Income or Basic Income (Cena y Dettano, 2022). The emotional map that unfolds regarding the management of a massive intervention of the pandemic in Argentina sheds light on a framework of feelings[3]. Uncertainties and expectations overlap along with anger, impotence, and fatigue produced by not knowing, not being able to build certainties in a scenario that threatens the basic conditions for the reproduction of life.

The different studies on anger lead us to reflect on power relations as well as on the spaces occupied by subjects in the social structure. As in the case of shame, anger refers to social configurations based on unequal relationships (Vergara, 2009). Experiencing anger is limited to stratification, socially established hierarchies, and the exercise of power, whose study warns about the processes involved in the formation of social status. As we will explore in the following sections, anger can either foster relationships of domination or transform them. This is why it is classified as a political emotion (Holmes 2004; Velasco Domínguez 2016).

According to Hansberg (1996), anger, along with admiration and resentment, are personal reactive emotions felt in the face of attitudes that other human beings have towards us. The author claims that people get angry about actions, omissions, or events that they wish had not happened. Anger and reactive emotions "require a complex system of personal relationships, the demands, and expectations that these relationships entail, their manifestation or non-manifestation in behaviour..." (153). Anger takes place in contexts that generate discontent, where there is evidence of a disconnection between what is expected from the situation and what is experienced (Holmes 2004). As can be seen, it always implies a cognitive act (Hochschild, 2011), where it is judged whether a situation or event is unpleasant or not for the person involved.

Schieman's question (2006:493) "What can we learn about social life by studying anger?", gains importance since analysing the anger that occurs in the collection of a social policy. Studying anger sheds light on the actors within the social policy, the obstacles they face, the practices, and the times involved. Contexts influence and affect the processes of any emotional state and anger is no exception (Schieman 2006). Deepening its study allows us to observe what is considered unfair, what is experienced as an offence, and who are the ones who commit injustices or faults that arouse anger.

The contextual, interactional, power, and historical dimension becomes central to the understanding of anger. As Schieman (2006) points out, although some dimensions of anger might involve neuroscience studies, social interactions are still relevant since they organize the context, the conditions, and the forms of its expression and definition. “As sociologists, our aims entail the description of those social conditions and their roles in the activation, course, expression, and management of anger as a process.” (495)

In this sense:

“Common elicitors of anger involve actual or perceived insult, injustice, betrayal, inequity, unfairness, goal impediments, the incompetent actions of another, and being the target of another person's verbal or physical aggression (Berkowitz and Harmon-Jones 2004; Izard 1977, 1991). One of the most prominent reasons for anger involves direct or indirect actions that threaten an individual's self-concept, identity, or public image (Cupach and Canary 1995); insults, condescension, and reproach represent these threatening actions (Canary et al. 1998). Collectively, these sites of anger provocation involve the perceptions of social conditions or current, objective circumstances. Major institutionalized social roles embedded in work and family contexts provide structure and organization for the conditions that expose individuals to the sites of anger provocation and pattern anger processes across core social statuses such as gender, age, and social class” (Schieman 2006: 495).

Based on the classic definitions of anger, this is a generic expression attributable to a range of emotions such as frustration, resentment or guilt. They emerge when people engage in processes with certain expectations only to find the outcomes do not coincide with the desired ones (Schieman 2006; Velásco Domiguez 2016; López Carrascal 2016).

The possibilities of experiencing anger, as well as the ways of expressing it, and the objects that motivate it, are distributed differentially according to socially established hierarchies, positions, and roles. In the examples studied by Schieman (2006) - the workplace, family, and home - various situations can arouse anger due to the incompatibility between expectations and behaviour. In addition to the different contexts where anger may arise, it is conceptualized as a process, which includes its activation, course, management, expression, and consequences.

The expression and management of anger have different consequences. As various studies reveal and illustrate, anger can be a destructive emotion yet it can also encourage people to transform unwanted conditions in their lives, confront these circumstances, and seek disruptions or modifications. Thus,

“the social process of anger can lead to reiterate or disrupt asymmetric power structures, as well as the identity conformations involved. If an individual situated in a high status (target level of power) resorts to anger, they reiterate the relations of domination. On the other hand, if an individual of low status wishes to ascend, anger can operate to subvert certain guidelines of the established order” (Velasco Domínguez 2016: 343-344).

In a similar vein, Nurit Shabel (2019) identifies the expression of tiredness and anger based on perceived discomfort and injustices experienced by social groups. The author pinpoints that anger emerges in the face of a feeling of injustice, that coexists with other feelings, such as frustration and fatigue, as well as recognizing others as peers in the feeling of discomfort. This is related to what Scribano (2020) calls emotional ecologies, groups of emotions that have “family resemblance” (p. 4). These are close emotions that share “a similar chromatic field” and occur in a certain social and geopolitical context. Such contexts enable or disable certain groups of emotions, a way of feeling and expressing them based on ways learned with others in society.

Silva’s study (2021) positions anger in terms of recognition -of certain situations experienced as unfair- and rescues its political efficacy, being a crucial motivator of collective action. The centrality of experiencing and acknowledging anger implies that others agree with the evaluation of the situation that generated it. In this way, the need for recognition relates to a modification of the definition and evaluation of the situation that gave rise to anger, and not necessarily to retribution.

In short, anger is the result of circumstances in which an individual loses power and status, where their expectations are not met, and where objective circumstances are experienced as unfair. It is an emotion that can be thought of procedurally, starting from an object or situation that originates or motivates it with a particular course or manner of expression. Their expressions do not always pursue a rupture or subversion of the established order, but can also pursue the recognition and legitimation of other peers.

3 Methodology

To fulfill the objectives of this article, we implemented an observation within the framework of a Virtual Ethnography, in a Facebook group about the EFI. For the selection of this strategy, the transformations identified in social policies have been considered from the incorporation of information and communication technologies and the Internet (Weinmann and Dettano, 2020; Cena, 2022) and the deployment of environments where people interested in social policies meet and interact such as WhatsApp groups, Facebook, Blogs, and YouTube channels (Cena, 2014; Sordini 2017; Dettano and Cena, 2020). Consequently, daily practices are situated in a world, by definition, “onlife”, understanding that lives inside and outside cyberspace make up a single social life where they overlap – overflowing the geographical and the face-to-face – a set of worlds of life, sociabilities, and experiences (Van Dijck 2016; Scribano 2017; Gómez Cruz & Ardevol 2013).

The fieldwork was carried out in a Facebook group, between August and September 2020. It reached approximately 200,000 members and presented a high flow of daily interactions, a significant aspect of a virtual environment (Anonymised 2020). The observation consisted of a daily publication record of the selected group in one of the EFI payment periods. There, we recorded comments from the participants about the collection of the benefits, registration, and the problems they were having in that process. The sampling of the publications and comments was carried out according to the criterion of maximum variation, trying to obtain the greatest diversity of attributes among our observation units. A gridding was held in the morning and another after 6:00 p.m. In each turn, two publications were selected and 10% of the comments of each one were archived according to gender parity criteria. The criteria for the selection of the publications were linked to the objective of this writing: to explore the emotions associated with the management, participation, and reception of the EFI within the framework of the COVID-19 pandemic. A written record was kept for 21 days, which allowed to grid 84 publications and 454 comments.

The use of a grid allowed a primary approach to the interactions that occurred in that setting, generating a first classification of the exchanges. Facebook groups are very dynamic virtual environments where, for example, a post goes from 0 to 41 comments in minutes. The amount of information generated, the speed of the exchanges, as well as the knowledge that circulates in the analysed environment, have required a registration strategy that combines the construction of a matrix, the generation of screenshots of the selected publications, and the preparation of a log.

The field notebook -or work log -, in addition to collecting our experiences, opinions, and provisional analyses during registration, also contributed to the validity of our observations. As Ardevol et al (2003) highlight, these first-person narratives contributed to making sense of the observed interactions. What was collected there, our impressions of the environment and its interactions were a clue to observe emotions linked to anger, fights, discussions, and conflicts.

One of the elements recorded in the work log is that such Facebook observation environments present "interaction rules" where their administrators dictate those behaviours to be avoided or prohibited. Insult and aggression appeared on several occasions as a form of relating with each other that is not welcome in these environments. The sale of products and services and the sharing of personal data were discouraged to prevent scams or fraud. As we pointed out on another occasion (Dettano and Cena, 2020), the different components of virtual environments (in this case, "the rules of interaction"), allow us to observe how interactions take place. What is prohibited is something that happens and is drawn to their attention through the establishment of rules.

These aspects were uploaded onto our work log: we could have a preview of the anxiety, the repetition of consultations, the aggressions, and conflicts that were being woven into the threads of conversation. Participants ask questions, and help each other by replying to queries, but also display ways of seeing the world and lecture on what behaviour is right/wrong as a beneficiary, which generates tensions and discussions.

In those conversation threads, different expressions are intertwined: the written word, images, and icons/emojis. Ardevol et al. (2003) recover that, although the textual character of the interactions prevails, other ways of communicating emerge, which represent different emotions, agreements, and ways of giving cues or allowing the other to continue their story. For the authors, the use of language is conditioned by the space where communication takes place, so in chats, publications and comments there is an "economic use of language" (11), using emojis, symbols, and abbreviations, which speeds up the pace of conversations.

Within these multimedia environments, different elements coexist, arouse, and enhance different emotional states (Serrano Puche 2016). The Facebook environment, in particular, offers different possibilities for interaction: the publication of images, text, and expressions of reactions, such as “likes” or other available emotional states such as "it makes me angry", "it amuses me", "it makes me sad", "it matters to me” (Papachirissi 2009). Access links to publications on other platforms, videos, and WhatsApp groups are also shared, transforming interactions into a “multi-platform" experience. In many cases, the interactions that initiate the publications of the analysed group are images such as screenshots: responses from ANSES, responses from the bank, and pages of the management applications of the program in question. These are accompanied by explanations and queries about the steps taken and requirements for the collection of the benefit, giving rise to queries from the image. This mode assumed by the interactions in the analysed environment constitutes the digitized word (Orellana López & Sánchez Gómez 2006). Text, image, audio, video, reactions, and emojis constitute the interactions and make up the content and form that said word is assumed in the environment under analysis, where the textual, hypermedia, and multimedia coexist.

4 Complementary senses about anger

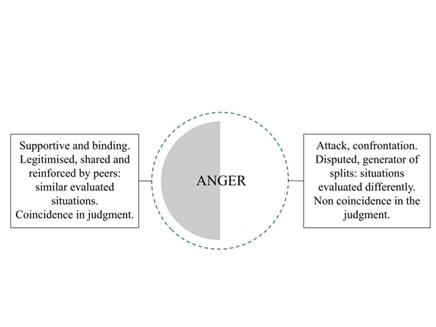

Emotions are not produced in a sealed way, some coexist with others; they overlap, and reinforce with each other. They have a contextual element, which in the case under study was influenced by isolation due to the pandemic. This motivated an entirely online management and collection of the EFI, involving feelings linked to uncertainty and waiting. The conditions in which life is produced and reproduced, such as occupation, educational level, and income, “reflect sources of status, inequality, and resources that link individuals to forms of social organization and culture that, in turn, influence emotional life” (Schieman 2006: 507). In this regard, the direct threat to the possibilities of subsistence that the pandemic context meant and the obstacles involved in managing and accessing the subsidy under study generated a range of emotions. Anger, alongside the previously mentioned feelings, was particularly prominent. (Graph I). In this line, this section develops 3 analytical axes that account for the dimensions that anger assumes in the reception of a social policy. Anger appears as a product of the mismatch between expectation and experience in the face of arbitrariness and irregular functioning in the implementation. This emphasises its binding and supportive nature that is shared in search of empathy and is reinforced by sharing it. Other aspects emerge by motivating anger: the logic and assessments about the deserving/not deserving of subsidies as well as politicians and government officials that appear as their legitimate recipients.

First of all, this emotion stems from having fulfilled all the necessary and required actions in the design of the program and yet not receiving the payment. A set of online/offline practices are deployed, without success, to address the delay in payment: calling the institution, repeatedly checking mobile applications to confirm the deposit of money, consulting Facebook groups, and so forth. For Nurit Shabel (2019), anger emerges from the feeling of injustice and coexists with other feelings, such as frustration and fatigue. In the expression, "what we have to do for ten thousand pesos!" (0830DMG), a cluster (or excess) of activities is exhibited. According to the threads of conversation, it does not seem to ensure any success in being granted the subsidy in a context of isolation:

Calls are not answered,; online

inquiries and the page are saturated,; dates are changed and you are not

notified, the SMS never arrives, and I understand that it is something that

comes from a higher level but an EFI of 10 thousand every two months! it is no

emergency. There are people who did not even get the first collection. After

they made you stay at home locked up for 100 days. It’s a shame! ![]() (0825LI)

(0825LI)

In the face of situations that threaten their reproduction recipients feel anger:

“Money may not be able to buy happiness, but not having enough money to pay for the basic needs or desired objects probably contributes to aggravation and dissatisfaction” (Schieman 2006: 499).

Sharing and exposing their own experience collecting the EFI, experiencing discomfort - "you can’t listen well", "they mistreat you" - and the impossibility of a solution - "I have the money deposited but it does not appear in my bank statement" - enables reactions that reinforce this range of feelings. These shared situations in the analysed Facebook environments facilitate the emergence of fatigue and anger because they hinder the possibility of reproducing life in conditions of scarcity. In this way, anger and conditions of production and reproduction of life are closely linked:

"THE TRUTH IS THAT I HAVE LOST ALL HOPE OF COLLECTING THE 2nd EFI. I call number 130 and they mistreat you. Besides, you can't hear what they are saying. I am tired. Since June I have had the money deposited and the bank does not show it." See attached photos 1 and 2 " (I like 94) (it saddens me 16) (it angers me 10) (it surprises me 3) (I love it 1) (it amuses me 1) (1008FM)

Reply: "yes, they pass the buck

to each other ![]()

![]() anger and impotence, I’m willing to

anger and impotence, I’m willing to ![]() " (1008LS)

" (1008LS)

Reply: "The same thing has been

happening to me since June 23rd; it is deposited supposedly in the Brubank;

you call number 130, 600 times and when they pick up they do not give you an

answer ...( “call next week” I'm tired) ![]() " 1 pisses me off and 3 comments (1008JR)

" 1 pisses me off and 3 comments (1008JR)

Feeling anger and sharing it awakes other feelings and judgments that reinforce it, contributes to its recognition as a valid emotion in a context and it is legitimized by peers. That is to say that in the interpretation of the situation, others share the evaluation of the experience as unfair, thus legitimising it by acknowledging others as peers in the feeling of discomfort. This is visualised through comments or repeated publications, the reactions that the Facebook platform enables, the number of likes, and the expression of emotional states such as "I get angry". Additionally, situations without a solution and that imply a state of uncertainty -"they pass the buck to each other", "when they pick up they do not give you an answer"- generate anger, impotence, expressions of anger (emoji) and even "desire to cry” (emoji).

Anger is expressed in a pandemic context that makes it possible to understand how this set of practices are lived (Scribano 2020). They are collectively reinforced and legitimised as: a) emotions resulting from situations that share similarities: “we are in the same situation”, “the same thing happens to me”; b) a product of the thread of interactions that sustains and strengthens feelings, such as comments and reactions -“I like it”, “it makes me angry”, “it makes me sad”- that a publication provokes.

Reply "we are in the same situation; me… since June 6/23" (1008EB)

Reply "the same thing happens to me" (1008AYO)

the truth is that it's tiring, I'm already giving up; I'm tired of it, and the third EFI is about to come out .... I had the option to change CBU number, I put the Bank's CBU but I never got the mail, so I'm sure I won't get paid this month either (1008JR)

The same thing happened to me, I complained, and that's how they answered me, in a bad mood. They are kidding me, they aren’t paying it anymore, they want everyone to get fed up and stop claiming it. What we should do, the millions of us who are going through this, is to tell Alberto (the president) to shove his lies up his ass and kick out this fool, the inept bitch who is laughing her ass off at everyone, since the other one was kicked out by the retirees' queues, and this bitch has had us begging for 10 thousand pesos for 4 months (2608NI).

Here anger is presented as a bonding and supportive feeling. Binding because they plan and unify similar experiences to the collection of the subsidy. In other words, they link the experiences of a massive number of EFI recipients that show a pattern: the mismatch between expectation and experience. Solidarity because they arouse adhesions; it is an emotion that is exposed, reinforced, and legitimised by others against a "common cause". Anger arouses empathy in Silva's terms (2021) when it is considered an appropriate feeling, "may be met with empathy when anger is seen as appropriate, as in such cases the [...] group shares the appraisal of those in anger" (17). In other words, it fosters empathic resonance (Vermot, 2014) since individuals share judgments and evaluations regarding the elements that contribute to what is considered unfair.

Other situations that arouse the anger of the EFI recipients have to do with the appearance of other actors who participate, influence, and are part of the social policy. Although we previously maintained that one of the dimensions of anger is being supportive and operating in a binding manner, it can also generate confrontations and divisions. The anger among peers involves the moral judgment on the destination given to the subsidy, the classification, and division between those who deserve and those who do not deserve the subsidy, and the construction of a "them" and an "us".

The EFI had a massive scope (De Sena 2011) but not universal. Concurrently, it implied discontinuities in its monthly disbursement and in the receiving population -those who received the first EFI did not necessarily receive the 3rd-. This irregular segmentation in payments and population is the object of anger and confrontation on the part of the population that "disputes" access to transferred subsidies that are always perceived as fleeting (Cena, 2018) and scarce (De Sena and Dettano, 2020). Anger also shows a moralizing and lecturing profile. While in some circumstances feeling anger is reinforced in a supportive and binding way, here it is presented as an object of controversy: those who participate in the interaction do not agree on the assessment of the situation. The perception of injustice or inequity in the transfer of income: "they do and I don’t" constitutes one of the central sites of provocation of anger in terms of Schieman (2006):

"Perceived inequity is one of the core sites of anger provocation. According to equity theory, perceptions of inequality [...] foster feelings of frustration and anger [...] Getting less than one feels that he or she deserves is an unfair or unjust state of affairs" (498).

What will be regarded as unfair or not and, therefore, what may or may not arouse anger, also responds to a particular distribution of power relations. These relations shape the circumstances in which anger is seen as justified and what it is directed toward:

“This means that the anger of the oppressed will be more easily dismissed as inappropriate due to a dominant ideology” (Silva 2021: 17).

It’s unfair that my wife was told that she should not receive the EFI because my daughter was born 2 months ago and she has not done the registration process; because it was paid by the universal child allowance, and I do not receive anything being unemployed, and she does not receive anything ....

It's really unfair to see how kids who

live with their parents and receive all the benefits spend it all on cell

phones and parties .... ![]() (1108JR)

(1108JR)

How do you know that those of us who get paid buy cell phones? I hope they never give it to you for being so prejudiced (1108MM)

Social action of each municipality should have taken a census of the people who signed up and given it to those who really need it. Here, in Roldán, there is a family whose son, the mother, and the grandmother receive it; the father works, there are thousands like them and then they complain if the government takes it away (2908OO).

Do not gluttonise on what the State gives you with the taxes we all pay (1608MO).

That seems very bad on the part of the

government. The EFI is for people who have nothing, like me; they don't have to

give it to people who get a salary ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() (1608SMB)

(1608SMB)

In the emotional worlds configured in the attempt to manage and access the EFI, anger is both reinforced by sharing experiences. Also, it increases the heat of discussions that are generated among the members of the group. If, as we observed, some conflicts and anger are organised after the evaluation of the behaviour or the merit of others, different conflicts and triggers also emerge. After pointing out, again and again, the strong need for a monetary benefit, a possible actor appears towards whom the anger should be directed: "the governments", "the politicians", and "those from above". These actors not only have an obligation, because "they are public servants" and "they steal money", but they are also the ones who have ordered and regulated the conditions of isolation in the pandemic.

Socially established hierarchies enable specific emotional distributions. While the recipients reiterate the urgency and the need for the monetary benefit in the context of a lockdown, the differences in status are emphasized, with those others who are claimed on, or towards whom the conflict should be directed. If we posit that frustration, resentment, guilt and anger are experienced from participation in processes with unwanted results, we can also maintain that, in many cases, this is attributed to others whose position and status are above their own.

For the Argentine case, Vermot (2014) recovered the fact that the social, economic, and political crisis experienced in 2001 encouraged many Argentinians to migrate, which ended up developing feelings of anger. The author presents frustration as the trigger for these emotions due to the inability to act in the face of a drop in their social scale, in the face of the loss of work, of income, as well as of the savings that the 2001 crisis brought about. Frustration, sadness, and anger appear, for Vermot (2014), not only before the transformation of the objective situation of the subjects -loss of social status- but also when perceiving the behaviour of politicians as repetitive, circular, and undignified.

DO NOT ARGUE!!! WE HAVE TO BECOME AWARE THAT IF WE ARE IN THESE CONDITIONS IT IS BECAUSE OF "THE" GOVERNMENTS IN POWER, THEY DO NOT CREATE DECENT REGISTERED JOBS. WE HAVE TO WAKE UP AND START DEMANDING THE POLITICIANS FOR ANSWERS. THAT'S WHAT THEY ARE FOR, THEY ARE PUBLIC SERVANTS WHO ARE PAID FOR DOING NOTHING (2808VV).

Let's stop attacking each other, the poor...Let's look at the one at the top who steals the money all and sends it abroad; in Canada it is required by law to subsidize (2808SG).

We have previously noted that anger is part of certain power relations and, as a political emotion, it can reinforce or erode its differential distribution. Additionally, if anger is the result of circumstances in which an individual loses power and status, "another actor" emerges who is responsible for that loss and who can compensate for the situation that has caused anger: "if we are in these conditions it is because of the "governments"; “we have to wake up and start demanding politicians to act”, “let's look at the one above us who steals everything”. In this way, “Expectations of control and the associated feelings of potency enable anger when events or outcomes deviate from a desired or anticipated path (and another person is blameworthy)” (Schieman 2006: 509).

Different objects arouse anger, each context indicates different modes of expression and channelling that legitimise and validate it. Anger is also generated by the actions of others that are considered incorrect, when an event or fact is perceived as unfair or when it threatens one's identity or status. It takes place when there is a perceived threat and a discrepancy between expectations and results. Anger warns of the positions occupied in the social structure, which allow or restrict the ability to act, to modify the state of affairs.

Graph 1: Anger in a pandemic context

Source: author’s own

Alt text Graph 1: Description of the dimensions of anger.

5 Conclusions

The pandemic context implied, among other risks, the threat to life and the possibilities of subsistence, with particular emphasis on the contexts of poverty and unemployment. This meant the development of a feeling (anger) that - along with uncertainty, waiting and fatigue - was shown repeatedly, expressing a particular emotional world.

The crisis scenario in the face of isolation required various state interventions aimed at compensating for the loss of income and sources of employment. In this way, social policies were the protagonists of state agendas, concentrating a series of problems, resources and operations to address the conflict situation. For this reason, they updated its inescapable character in accumulation regimes. On the other hand, they regulated these conflicts and their expressions, showing once again their ability to model and construct the bodies/emotions of the intervened populations.

Anger is experienced when a situation is assessed and regarded as threatening to the reproduction of life. This emotion appears, in the first place, reinforced when several people make the same interpretation of the situation: it is an emotion validated and legitimised within the context. Such was the case in situations that hindered or delayed access to and collection of the EFI for subsistence: bureaucracies, situations that do not correlate with the program regulations, to name a few. That is why we have affirmed that it is binding -by plotting and unifying similar experiences in transit through the EFI- and supportive -by awakening adhesions or empathic resonance in the face of a shared experience and interpretation-.

In a complementary sense, anger generates confrontations and divisions. It is driven by situations that are not evaluated in the same way: among peers, by the “dispute” in the access and distribution of the EFI, the controversy over the merit of the benefits and the destination of the funds, etc. Similarly, within these confrontations, other actors, such as politicians, and "the government in power" appear in the interactions, generating anger by staging the difference in status and how it becomes detrimental to those who participate in social policies. These actors, accused of corrupt practices, are the ones targeted by the anger and conflict generated by the waiting, fatigue, and uncertainty produced by the process of accessing the subsidy in a context of crisis.

Reviewing the paths and theoretical developments on anger allowed us to notice the contexts, practices, and mutual expectations that originate and shape this emotion. Studying anger concerning state interventions adds a bonus: it accounts for the positions and plots that are organised in the attempts to access different subsidies. What or who are the ones that arouse anger? where and how is it channeled into? and what elements reinforce or diminish it in virtual environments such as Facebook groups? In the studies on this emotion, it appears capable of modifying the existing order, the positions, and the inequities that mobilize it. The anger aroused by the management and attempts to access the EFI in the pandemic organises the question for us about what arouses this feeling. Although not homogeneous, anger warns about feelings of injustice and inequity, evaluations about the deservingness of the benefits and the dispute over access, as well as those actors who appear responsible for the situation. Now, the journey through the different elements that motivate and increase this emotion leaves us with some questions about its scope and potential: does the anger that resonates in these groups subvert any order or situation? or Is “empathic resonance” and the feeling of legitimacy with others the limit?

Finally, our study allows us to reflect on the concrete experience of social policy. Beyond the objectives outlined in the programs and policies, which aim to combat exclusion, accompany people in vulnerable situations, and reduce inequalities, among other possible things, this work and how anger appears allow us to reflect on the complexities of program implementation. It also sheds light on how social policy shapes emotions. This is exacerbated in a context of isolation due to the pandemic and the forced digitalisation of the registration, claims and consultation processes. On this, the following are recommended: mediation for digitalization processes; clear, concise, and uniform information on all platforms; regularity in payments; attention and assistance to recipients; clear measures and government transparency.

By studying anger, we can reveal the obstacles, the practices, and the times inherent in the State interventions, and thus redesign and improve the implementation processes of social policies based on the experiences of the recipient population. Anger is a social symptom, its study aims to guide future processes of implementation of social policies.

References:

Administración Nacional de la Seguridad Social (2020). Boletín IFE I-2020: Caracterización de la población beneficiaria. Dirección General de Planeamiento – julio 2020. Disponible en: http://observatorio.anses.gob.ar/archivos/documentos/Boletin%20IFE%20I-2020.pdf

Ardèvol, E., Bertrán, M., Callén, B. y Pérez, C. (2003). Etnografía virtualizada: la observación participante y la entrevista semiestructurada en línea. Athenea Digital. Revista de pensamiento e investigación social, (3), 72-92.

Betzelt, S. & Bode, I. (2022). Emotional regimes in the political economy of the ‘welfare service state’. The case of continuing education and active inclusion in Germany. Working Paper, No. 178/2022. Institute for International Political Economy Berlin.

Cena, R. (2014). Acerca de las sensibilidades asociadas a las personas titulares de la Asignación Universal por Hijo, un análisis desde la etnografía virtual, en Las Políticas Hechas Cuerpo y lo social Devenido Emoción: Lecturas Sociológicas de las Políticas Sociales, pp. 155–86. Estudios Sociológicos Editora.

Cena, R. (2018). Los tránsitos por la inestabilidad: hacia un abordaje de las políticas sociales desde las sensibilidades. En A. De Sena (Comp.), La intervención social en el inicio del siglo XXI: transferencias condicionadas en el orden global, pp. 231-252. Estudios Sociológicos Editora.

Cena, R. (2022). ¿Dónde están las Políticas Sociales? sobre intervenciones estatales y procesos de digitalización en las sociedades 4.0. EHQUIDAD. Revista Internacional de Políticas de Bienestar y Trabajo Social, (18), 243-262.

Cena, R. & Dettano, A. (2022). ¿Quiénes hacen la política social? tramas de actores, acciones, (des)intereses y emociones en administradores de grupos de Facebook vinculados a las políticas sociales. En Sordini, M. V. Hacer políticas sociales: estudios sobre experiencias de implementación y gestión en América Latina. (157-186). Estudios Sociológicos Editora.

Criado, J. I. (2022). Tecnologías y políticas sociales en América Latina. Estado & comunes, revista de políticas y problemas públicos, 2(15), 153-157.

Cruz, E. & Ardèvol, E. (2017). Ethnography and the Field in Media(ted) Studies: A Practice Theory Approach. Westminster Papers in Communication and Culture 9(3), 27-46. doi: https://doi.org/10.16997/wpcc.172

De Sena, A. (2011). Promoción de microemprendimentos y políticas sociales:¿ Universalidad, focalización o masividad?, Una discusión no acabada. Pensamento plural, (8), 37-63.

De Sena, A. y Dettano, A. (2020). Atención a la pobreza y consumo: las intervenciones del “no alcanza”. En: Dettano, A. (Comp.) Topografías del consumo. (139-178). Estudios Sociológicos Editora.

De Sena, A. and Scribano, A. (2020). Social Policies and Emotions: a look from a global south. PalgraveMacmillan.

Dettano, A. & Cena, R. (2020). Precisiones teórico-metodológicas en relación a la definición de Entorno en Etnografía Virtual para el análisis de políticas sociales. Revista Tsafiqui. N°15, Dic. 2020. Disponible en: https://revistas.ute.edu.ec/index.php/tsafiqui/article/view/precisiones-teorico-metodologicas-en-relacion-etnografia/555

Dettano, A. & Cena, R. (2021). Políticas Sociales en contexto de pandemia: dimensiones de la incertidumbre acerca del Ingreso Familiar de Emergencia en Argentina. Sphera Publica, Vol.1, N°21. (pp.137-158). http://sphera.ucam.edu/index.php/sphera-01/article/view/415/14141477

Donzelot, J. (2007). La Invención de lo social: ensayo sobre el ocaso de las pasiones políticas. Buenos Aires: Nueva Visión.

Eriksson, P. K. (2016). Losing control in pre-adoption services: Finnish prospective adoptive parents emotional experiences of vulnerability. Social Work & Society, 14(1).

Greer, S.; Jarman, H.; Falkenbach, M.; Massard da Fonseca, E.; Raj, M. & King, M. (2021). Social policy as an integral component of pandemic response: Learning from COVID-19 in Brazil, Germany, India and the United States, Global Public Health, 16:8-9, 1209-1222, doi: 10.1080/17441692.2021.1916831

Hansberg, O. (1996). De las emociones morales. Revista de Filosofía, IX(16): 151-170.

Heller, A. (1980). Teoría de los sentimientos. Barcelona: Editorial Fontamara.

Hochschild A. R. (2011). La mercantilización de la vida íntima. Apuntes de la casa y el trabajo. Buenos Aires: Ed. Katz.

Holmes, M. (2004). Feeling Beyond Rules: Politicizing the Sociology of Emotion and Anger in Feminist Politics. European Journal of Social Theory, 7(2), 209–227. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368431004041752

Jupp, E. (2022). Emotions, affect and social policy: austerity and Children’s Centers in the UK. Critical Policy Studies. 16(1)19–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/19460171.2021.1883451

López Carrascal, L. (2016). Las emociones como formas de implicación en el mundo. El caso de la ira. Estudios de Filosofía, 53: 81-101.

Mac Auslan, I. & Riemenschneider, N. (2011). Richer but Resented: What do Cash Transfers do to Social Relations? IDS Bulletin. 42(6):60-66, doi: 10.1111/j.1759-5436.2011.00274.x

Martínez Franzoni, J. & Sánchez Ancochea, D. (2022). ¿ Puede la covid-19 avanzar la política social inclusiva? Las transferencias monetarias de emergencia en Centroamérica. Fundación Carolina, Documentos de trabajo, 60. https://www.fundacioncarolina.es/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/DT_FC_60.pdf

Nercesian, I; Cassaglia, R. y Morales Castro, V. (2021). Pandemia y políticas sociosanitarias en América Latina. Apuntes vol.48 no.89. http://dx.doi.org/10.21678/apuntes.89.1466

Nurit Shabel, P. (2019). “Porque nos daba bronca”. Las emociones en la producción de la acción política de niños/as en una casa tomada. Revista de Antropología Social 28(1), 117-135.

Orellana López, D. & Sánchez Gómez, M. C. (2006). Técnicas de recolección de datos en entornos virtuales más usadas en la investigación cualitativa. Revista de investigación educativa, 24(1): 205-222.

Papacharissi, Z. (2009). The virtual geographies of social networks: a comparative analysis of Facebook, LinkedIn and AsmallWorld. New Media & Society 11 (1-2): 199-220, doi: 10.1177/1461444808099577

Schieman, S. (2006). Anger. In: Stets, J. and Turner, J. H. (comp.). Handbook of the Sociology of Emotions. 493-515. Nueva York: Springer Science+Business Media, LLC.

Scribano, A. (2010). Primero hay que saber sufrir…!!! Hacia una sociología de la ‘espera’como mecanismo de soportabilidad social. In: A. Scribano and P. Lisdero Sensibilidades en juego: miradas múltiples desde los estudios sociales de los cuerpos y las emociones, (comps.) 169-192, Córdoba: CEA-CONICET.

Scribano, A. (2017). Miradas cotidianas. El uso de Whatsapp como experiencia de investigación social. Revista Latinoamericana de Metodología de la Investigación Social – ReLMIS, 7(13), 8-22.

Scribano, A. (2020). La vida como Tangram: Hacia multiplicidades de ecologías emocionales. Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios sobre Cuerpos, Emociones y Sociedad (RELACES), 12(33), 4-7.

Serrano-Puche, J. (2016). Internet y emociones: nuevas tendencias en un campo de investigación emergente. Comunicar, vol. XXIV, núm. 46, 19-26.

Silva, L. L. (2021). The Efficacy of Anger: Recognition and Retribution. In Falcato, A., Graça da Silva, S. (eds) The Politics of Emotional Shockwaves, 27-55. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham.

Sordini, M. V. (2017). El uso de internet en relación a programas sociales. Sapiens Research, 7(2),51-64.

Tonkens, E., Grootegoed, E., & Duyvendak, J. W. (2013). Introduction: Welfare state reform,recognition and emotional labour. Social Policy and Society, 12(3), 407-413.

Van de Velde, C. (2022). A global student anger? A comparative analysis of student movements in Chile (2011), Quebec (2012), and Hong-Kong (2014). Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 52(2), 289–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2020.1763164

Van Dijck, J. (2016). La cultura de la conectividad: una historia crítica de las redes sociales. Buenos Aires: Siglo XXI Editores.

Velasco Domínguez, L. (2016). Emociones, Orden de Género y Agencia. Verguenza e Ira entre mujeres indígenas originarias de los Altos de Chiapas. In M. Ariza (coord) Emociones, afectos y sociología: diálogos desde la investigación social y la interdisciplina 329-372. México: UNAM, Instituto de Investigaciones Sociales.

Vergara, G. (2009). Conflicto y emociones. Un retrato de la vergüenza en Simmel, Elías y Giddens como excusa para interpretar prácticas en contextos de expulsión. In C. Figari and A. Scribano (comp.) Cuerpo(s), Subjetividad(es) y Conflicto(s): hacia una sociología de los cuerpos y las emociones desde Latinoamérica. 35-52. Buenos Aires: Ciccus-Clacso.

Vermot, C. (2014). Los sentimientos de pertenencia a la nación de los inmigrantes argentinos en Miami y Barcelona. Boletín Onteaiken 17:30-45.

Weinmann, C. & Dettano, A. (2020). La política social y sus transformaciones: cruces y vinculaciones con el ciberespacio”. En: Dettano, A. Políticas sociales y emociones: (per)vivencias en torno a las intervenciones estatales. (147-170). Estudios Sociológicos Editora.

Author´s

Address:

Andrea Dettano

National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET)

Bogotá 1840, 1°B, CP 1406. Ciudad de Buenos Aires

+5491138787424

andreadettano@gmail.com

https://www.conicet.gov.ar/new_scp/detalle.php?keywords=&id=42705&datos_academicos=yes

Author´s

Address:

Rebeca Cena

National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET)

Boulevard Alvear 1334, CP 5900, Villa María, Córdoba, Argentina

+549 1169184897

rebecena@gmail.com

https://www.conicet.gov.ar/new_scp/detalle.php?id=38594&datos_academicos=yes